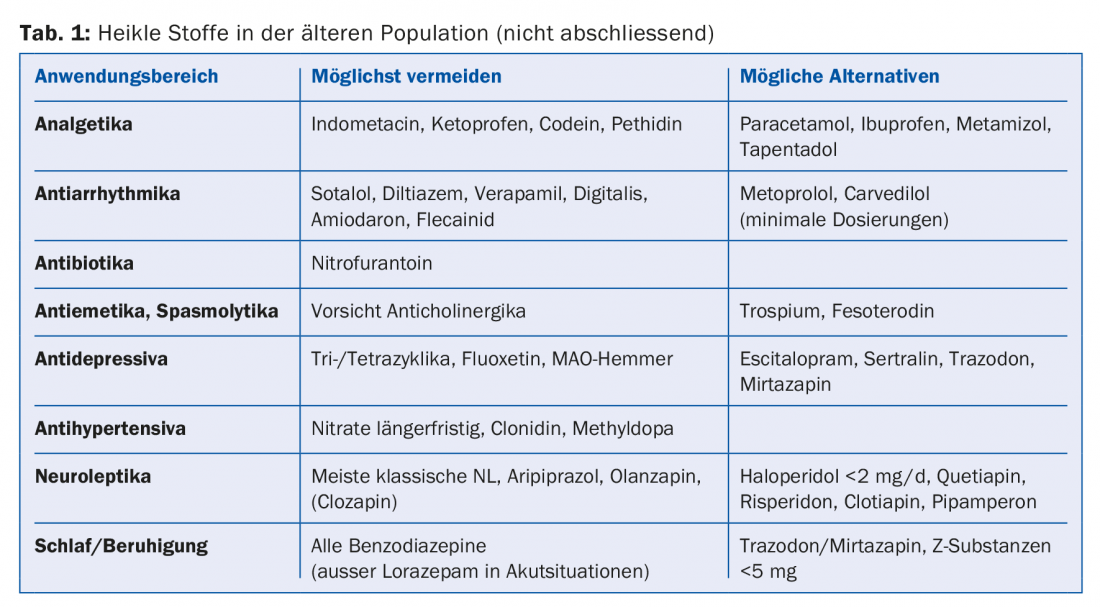

Various lists provide information on potentially sensitive substances in the geriatric population. Regardless of this, a regular review of indication, dosage, dosage form and risk/benefit of medications is indicated.

A significant portion of the primary care physician clientele is in the 65+ segment. The number of elderly patients will continue to grow for at least 30 years, in line with known demographic trends. People are considered “multimorbid” if they have at least three relevant disease entities, depending on the source. It is well known that the number of conditions or clinical manifestations increases with the number of drugs prescribed (approx. three substances per condition) – at the same time, several prescribing offices (general practitioner, specialists, hospitals) are usually involved, which can create additional interface problems. A large proportion of people over 65 take more than five medications at a time, and the number is somewhat higher in nursing institutions. In this context, it should also be noted that for a large number of drugs there are no studies on their use in the elderly or with existing other medications (these circumstances are regularly considered as exclusion criteria).

However, it should also be noted that any risks should not be linked exclusively to increasing age, as there are – also increasingly – older people who are extremely active both physically and mentally. The use of medications should be appropriately tailored to the individual’s particular functionality.

Potentially risky pharmacological substances

Pharmacological substances potentially risky for the elderly have long been identified and recorded in corresponding lists such as the Beers list (USA) [1], Priscus list (Germany) [2], in the STOPP/START criteria (Ireland) [3] or in the FORTA system (Germany/Austria) [4]. The policy work of Garfinkel et al. [5] shows that with the application of a good algorithm, an astonishingly large number of drugs (about 50%) can be omitted without negative consequences, especially for patients in one institution.

In some cases, the lists not only provide an overview of which substances are better avoided, but also encourage the use of certain preparations in defined clinical situations on a well-founded basis (do’s and don’ts). The results or contents of the lists and recommendations have long since found their way into various guidelines on medication in the elderly in Anglo-Saxon and German-speaking countries [6–8].

The recommendations of these “systems” not infrequently run counter to guideline-compliant treatments of younger patients (mostly specialty-related). It is important to note that guidelines are not “rules” that have to be followed; accordingly, adjustments and changes should be possible.

Here is where caution is needed in family practice and homes

Table 1 contains a selection of substances that should only be used with caution or better not (they all appear in the lists already mentioned). The list is influenced by my personal experience to date and contains mostly agents that are likely to be of primary care practice and/or institutions for the elderly. The recommendations are justified either by directly expected adverse drug reactions and/or by a high interaction potential.

The substances mentioned as alternatives also have side effects. The deteriorating renal function with increasing age must be taken into account (for practice and home use well usable the GFR according to Cockcroft-Gault, simple online tools available). Important are possible electrolyte disturbances under therapy with diuretics or antidepressants. Particularly vulnerable with regard to centrally acting drugs, especially classical/typical antipsychotics, are people with Parkinson’s-like diseases (cautious indication, low dosage and, in case of doubt, consultation with geriatric psychiatry/neurology).

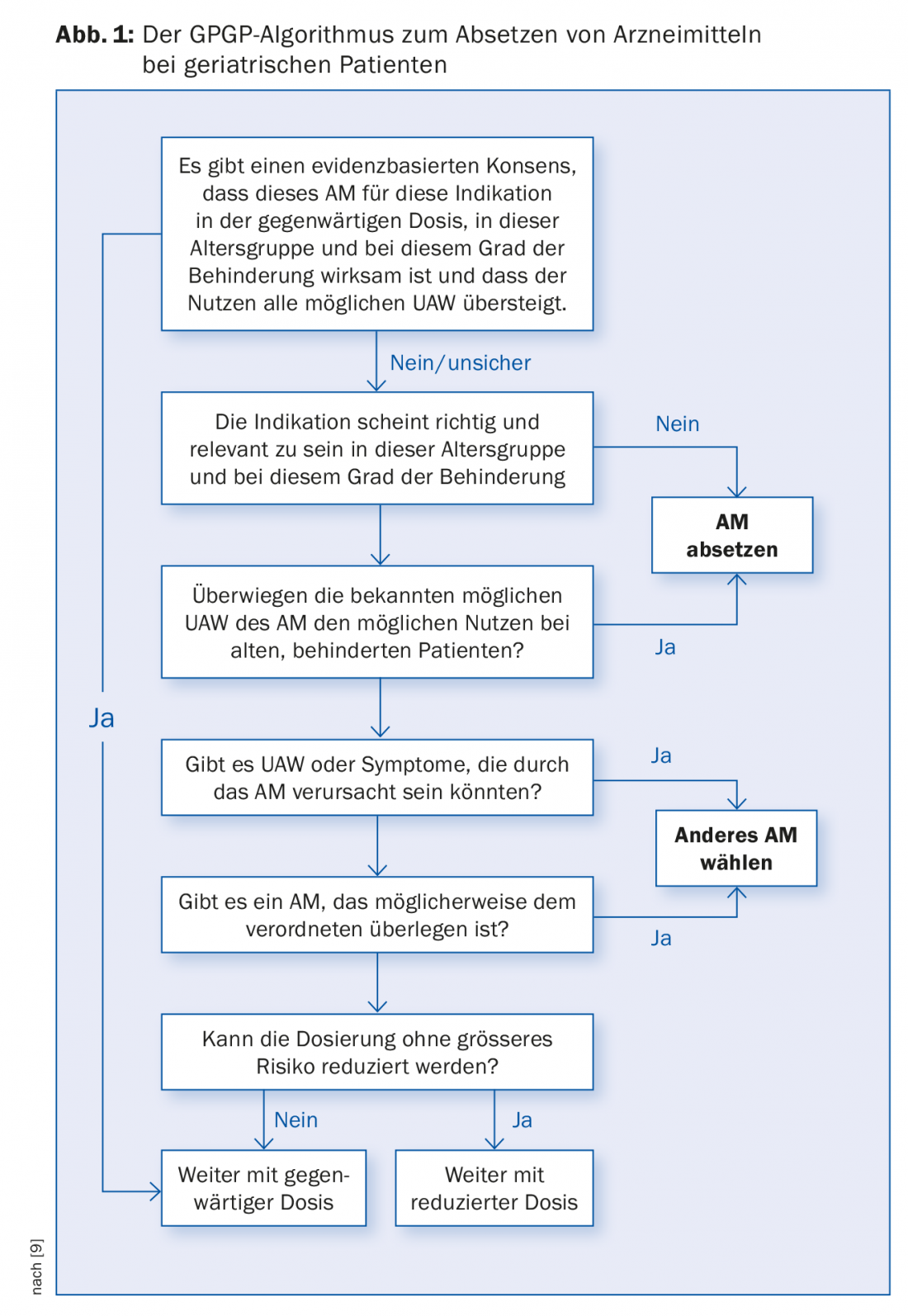

It is worth checking in principle whether a medication is indicated at all, and if so, whether it is correctly dosed and prescribed in a galenic form that is right for the patient. With this in mind, the Good Palliative Geriatric Practice decision scheme was originally developed by Garfinkel et al. and has found its way into many current recommendations in an adapted form (Fig. 1) [9].

Drug treatment of the vulnerable population of very old and simultaneously multimorbid residents of institutions for the elderly represents a particular challenge (and would even be worth a separate article). Problems are almost always initially of a logistical nature, such as the completely different processes of institutional and practice operations, evaluation of the information provided by the nurses, usually by telephone, under time pressure, usually impossibility of a rapid presence on site due to overloaded practice, etc. Medication lists quickly become longer than desired due to the usually high incidence of complaints and grievances, especially in the case of psychiatric accompanying symptoms of people suffering from dementia, who make up the large proportion of residents in our institutions for the elderly.

A systematic review of medication lists can be helpful in this regard (e.g., schedule special “medi-visit” in the home). After a new substance has been used, feedback on tolerability/effectiveness must be received within a defined period of time so that adjustments can be made or stopped in good time – a central point of cooperation between the institution and the doctor’s office and one of the guarantees that the medication lists remain as short as possible.

But: In the end, it’s not just about eliminating as many drugs as possible. In certain situations, an additional substance is definitely indicated and should be used if it is of predominant benefit to the patient. It is often possible to replace an indicated but risky drug with one that is better tolerated.

In conclusion

Generally established therapies should also be questioned in their use, especially in the very elderly. Example: Beta-blockers routinely used after myocardial infarction reduce mortality by about 25%, but the not uncommon adverse side effects such as malaise, palpitations, nausea, and dizziness can negate the positive effect by impairing the quality of daily life. Data exist that beta-blockers can exacerbate preexisting cognitive and functional impairment [10], which is quite consistent with my clinical experience in recent years.

Take-Home Messages

- Guidelines are not rigid rules.

- Less suitable substances can be found in the Beers list (USA), PRISCUS list (Germany), in the STOP/START criteria (Ireland) or in the FORTA system (Germany/Austria).

- There should be a regular review of indication, dosage, dosage form and risk/benefit (GPGP algorithm).

- A defined feedback practice for new medications used in homes is recommended.

Literature:

- American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel: American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012 Apr; 60(4): 616-631.

- Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA: Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010 Aug; 107(31-32): 543-551.

- O’Mahony D, et al: STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Ageing 2015 Mar; 44(2): 213-218.

- Pazan F, et al: The FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List 2015: Update of a Validated Clinical Tool for Improved Pharmacotherapy in the Elderly. Drugs Aging 2016; 33(6): 447-449.

- Garfinkel D, Mangin D: Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170: 1648-1654.

- Neuner-Jehle S, Krones T, Senn O: [Systematic elimination of prescribed medicines is acceptable and feasible among polymorbid family medicine patients]. Practice 2014; 103(6): 317-322.

- DEGAM: GP guideline on multimedication. Recommendations for managing multimedication in adult and geriatric patients. Updated 2014.

- Beise U, et al: Medix guideline medication safety. Updated 2016 Jun.

- The drug letter: an algorithm for shortening drug lists, because less is more. Web document. 2010.

- Stuck A: Update on known medications in elderly patients. Swiss Medical Forum 2018; 18(3): 46-48.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(3): 23-25