Tick bites are common – serious diseases are rare. Vaccination should be actively recommended to persons in endemic areas.

Tick-borne diseases are common, and questions about the risks, their prevention and treatment are part of everyday life in the general practitioner’s office and emergency departments (Fig. 1). Some daily newspapers have discovered the topic and present it in a sometimes lurid way. In addition, many patients seek information on the Internet, of which there is a myriad (>2 million hits). It is up to the primary care physician to know the facts and provide rational answers to the many questions.

Ticks

Ticks are insects that can be found in Switzerland up to an altitude of approx. 1500 m.a.s.l. occur. About a quarter of the ticks in Europe are infected with pathogens and can transmit them to mammals or humans. Ticks do not specifically seek out humans for their blood meals, but mostly rodents and other mammals. They can transmit a variety of pathogens: viruses (TBE; Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever), bacteria (Borrelia, Rickettsia), protozoa (Babesia). The clinic and treatment of tick-borne diseases are correspondingly variable. The most important diseases in Switzerland and Central Europe are early summer meningoencephalitis (TBE, about 1% of ticks infested) and Lyme disease (25-30% of ticks infested), rarely tularemia can also be transmitted by ticks.

Epidemiology, seasons

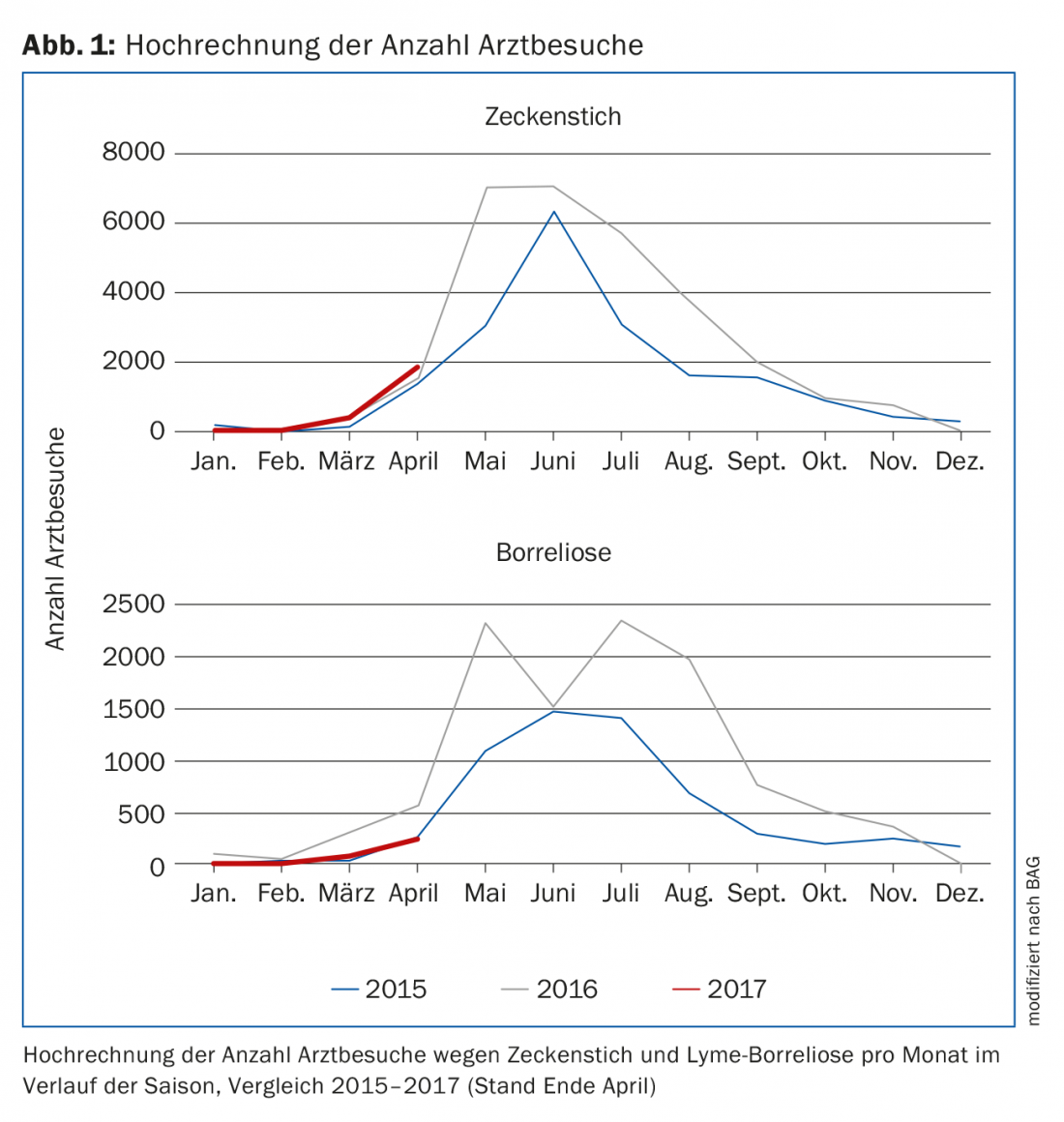

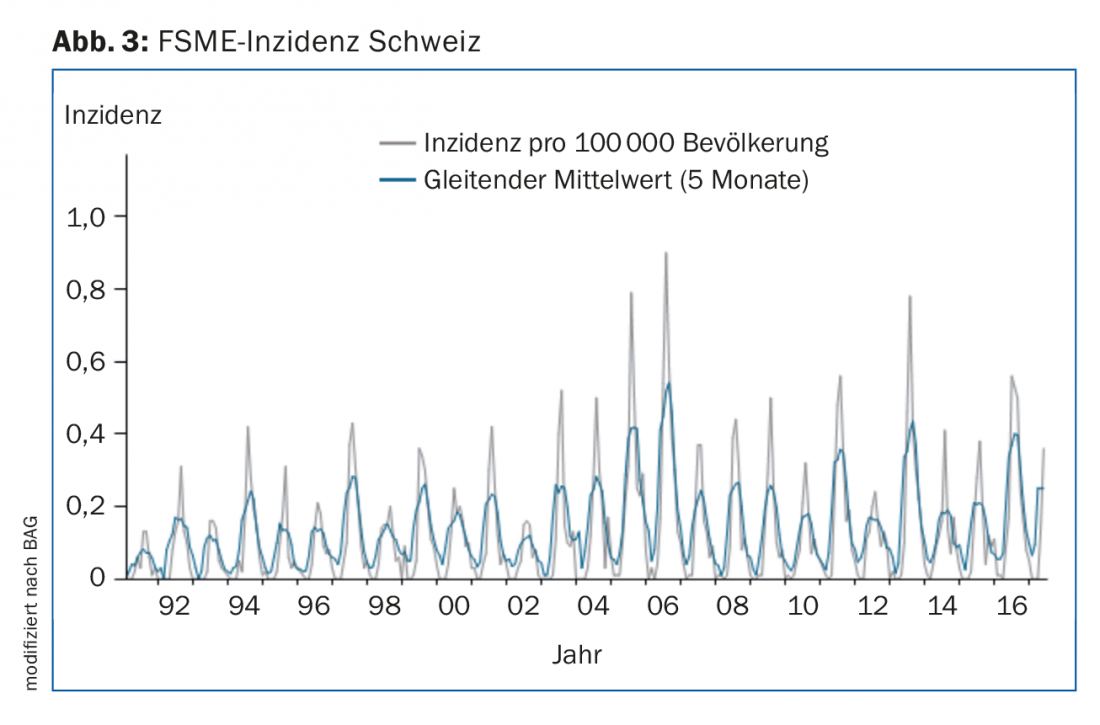

Ticks are active during the warm season and bites and illnesses are reported from about February through November. The number of consultations for tick bites and Lyme disease has been recorded in Switzerland for several years, as has the incidence of TBE. Larger year-to-year fluctuations occur, but overall the incidence is stable over the long-term [1].

Tick bite – what to do?

Ticks in themselves are not dangerous. They should be removed as soon as possible after the bite or discovery, since the risk of transmission, especially of Borrelia, increases with increasing duration of the blood meal. Overall, symptoms occur in only about 1-5% of individuals who suffer a tick bite [2]. After removal (as completely as possible, e.g. with fine tweezers), the puncture site should be disinfected. Antibiotic prophylaxis after tick bite is not recommended [3], but the bite site should be checked in the following days to detect possible erythema chronicum migrans. Special tick tweezers are not necessary and the removed ticks should not be examined for pathogens, as is sometimes recommended on the Internet: There are no validated examination methods and no studies that show a benefit of such an analysis.

Lyme disease

Borrelia are bacteria from the group of spirochetes. They are common and occur in tick populations throughout Switzerland. The pathogen was discovered in 1981 by the Swiss Willy Burgdorfer as the causative agent of Lyme disease. A large number of infections are asymptomatic. In Switzerland, the seroprevalence (antibodies against Borrelia) in the population is about 5-10%. Depending on exposure risk and geography, it can be significantly higher: Antibodies have been found in up to 26% of orienteers [4], most of whom never had symptoms.

Erythema chronicum migrans may occur one to two weeks after a tick bite. This need not be limited to the stitch site, but may also appear multifocal. It is not infrequently associated with nonspecific “flu-like” general symptoms. If suspected, it must be actively sought. The diagnosis of ECM is made purely clinically and does not require serology, since this is already positive in only at most half of the cases.

Weeks to months after exposure, organ manifestations may occur [5]; foremost among these are arthritis, meningoradiculitis, and very rarely carditis.

Arthritis is subacute and affects one or more of the large joints. This often reveals a pronounced effusion with few acute signs of inflammation (little pain, no fever, no redness). Differentially, therefore, another bacterial cause can be quickly ruled out, while crystal arthropathy, activated osteoarthritis, or other rheumatologic causes should be considered. If a puncture is performed, pathogen detection can be attempted by PCR in the punctate. During arthroscopy, the surgeon should be made aware of the possibility of PCR in the synovial biopsy.

Neuroborreliosis can cause a wide variety of neurological symptoms. Especially polyradiculitis with radicular pain leads to differential diagnostic differentiation problems with degenerative changes: In suspected cases, a lumbar puncture with determination of intrathecal antibody production (CSF-serum quotient) must be performed.

Borrelia serology is positive in more than 90% of cases of second-stage disease; however, in individual cases with early symptom onset, it must be repeated after a few weeks.

Late forms

Acrodermatitis atrophicans is a residual condition after untreated Borrelia infection that is seen extremely rarely. The atrophy of the connective tissue is definite and cannot be changed by antibiotic therapy. In late neuroborreliosis, a positive CSF serum antibody quotient must be present to confirm the diagnosis.

For the treatment of the different stages of Lyme disease, please refer to the guidelines of the Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases [6].

TBE

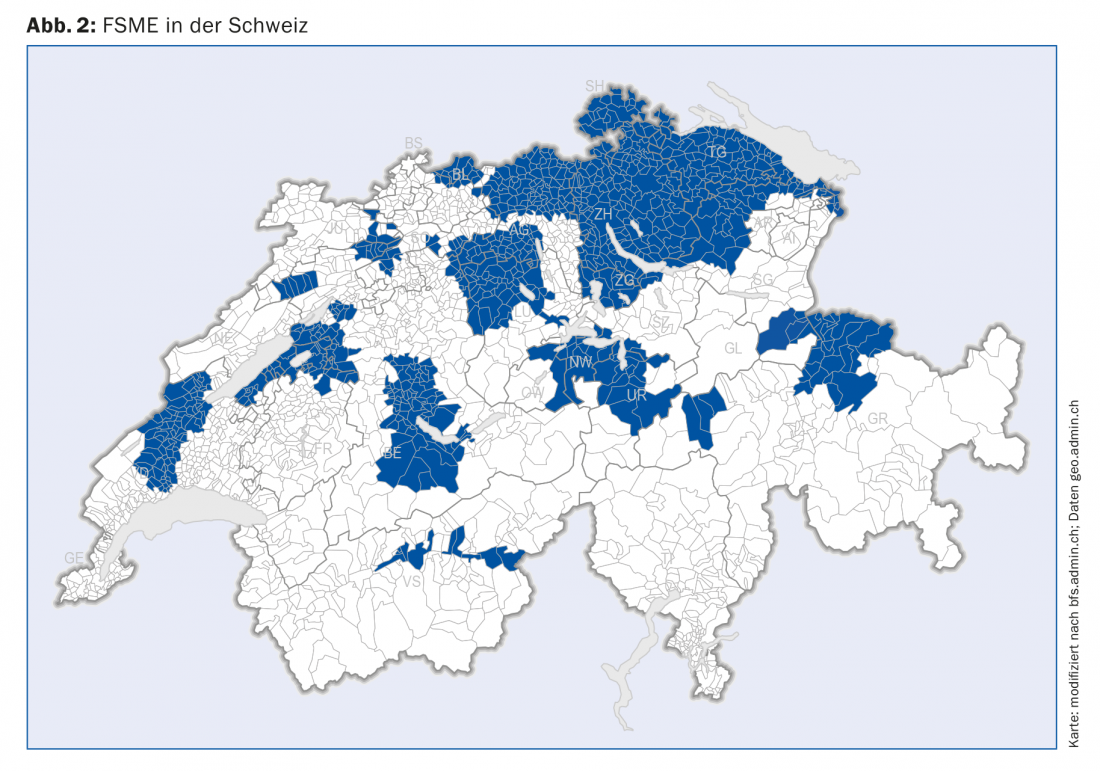

Early summer meningoencephalitis (English: “tick borne encephalitis”) is an infection caused by a flavivirus that is widespread in Europe and Asia in the temperate to northern zones. In Switzerland, the endemic areas have spread strongly in the Central Plateau in recent years, so that today a large part of the population is permanently or at least partially at risk of exposure(Fig. 2). In Switzerland, about 100-200 cases per year are reported (incidence, Fig. 3).

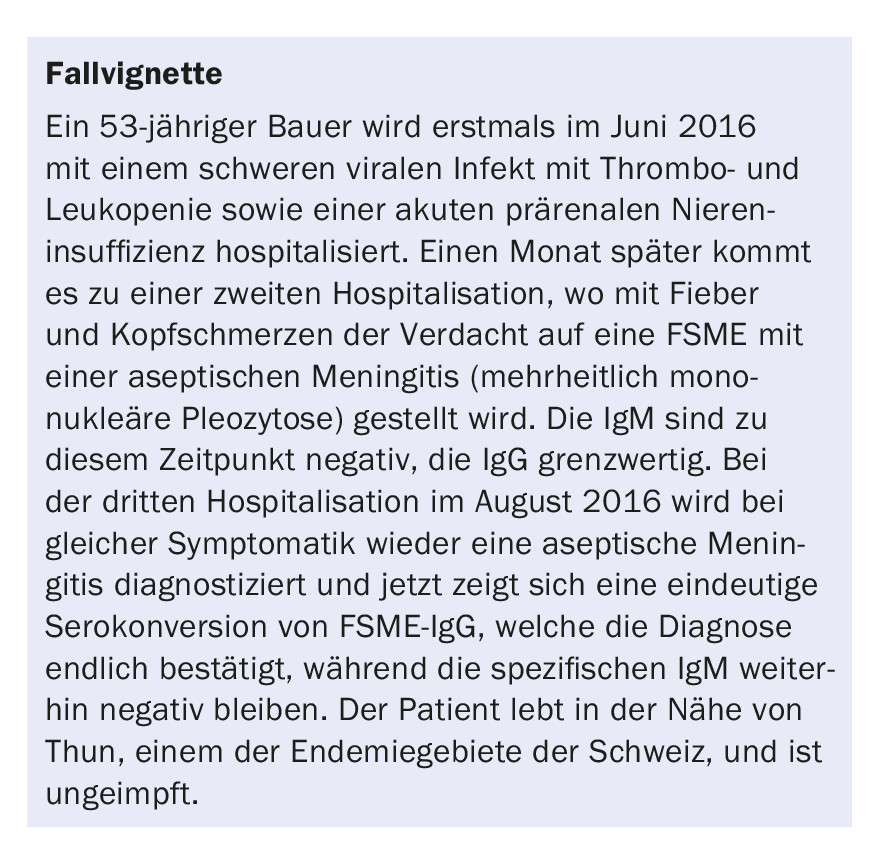

The course is typically bipartite, with both phases of the disease being mild or very severe (case vignette in box).

In addition to harmless courses with only “flu-like” symptoms, encephalitis is a severe disease that can be very protracted, often leaving residuals, and also has a mortality.

The diagnosis is made serologically, bearing in mind that antibody conversion (TBE IgG and IgM) has sometimes not yet occurred at the onset of symptoms, which is why progression serology is indicated after two to three weeks in cases of suspicion. Lumbar puncture reveals mixed-cell pleocytosis, protein proliferation, and normal glucose. PCR studies in CSF for herpes viruses are performed to rule out the differential and are negative, as are bacterial cultures. The treatment is supportive.

Misdiagnosis Lyme disease

Since Lyme disease is a disease with a very diverse clinical picture and often inconclusive diagnosis (high seroprevalence in healthy individuals), there is a risk that other diseases are falsely labeled “Lyme disease”. However, if these are now treated with antibiotics, no improvement will occur.

Various studies have been published on the value of repeated antibiotic treatments, confirming that no benefit can be achieved with repeat antibiotic therapy for symptoms with a lack of response. Persistent symptoms after correct antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease may either be explained by an incorrect diagnosis or reflect a delayed response. Again, long-term therapy of three months after initial antibiotic treatment showed no additional benefit [7], so it should be avoided.

The fact that repeated antibiotic therapy for persistent symptoms after Lyme disease treatment does not bring any benefit is also confirmed in a detailed review [8]. In these patients, good information and the careful and rational clarification of differential diagnoses, whether from the rheumatological, degenerative or psychosomatic spectrum, are important.

Prevention

The risk of tick bites can be reduced by protective clothing (long pants, long sleeves) and repellents. After spending time outside, the body should be searched for ticks and these should be removed quickly.

There is no specific Borrelia prevention and preventive antibiotic therapy after tick bite is not recommended – the ratio of side effects/risks to benefits is unfavorable.

TBE can be prevented by a well effective vaccination and should be recommended to all persons who regularly or temporarily stay in risk areas – i.e. a large part of the Swiss population. Vaccination is covered by basic insurance if indicated. Nevertheless, a great many people are not vaccinated, either because of their own ignorance or because their family doctor underestimates the risk (vaccination rates at about 42%).

Vaccination with inactivated viruses is well immunogenic, but relatively often (>20%) results in general symptoms such as fever, flu-like symptoms or headaches. It is important to inform about this as well. After basic immunization (months 0, 1, 6-12), booster vaccination is recommended after ten years. Individuals who have undergone TBE do not need vaccination; they have lifelong protective antibodies [9].

Take-Home Messages

- Tick bites are common – severe disease is rare.

- Lyme serology without a matching clinic is not helpful and leads to confusion.

- IgM alone are unreliable.

- The vaccination indication for TBE is common and vaccination should be given to all

- Actively recommend to residents of and visitors to endemic areas.

Literature:

- BAG: Tick-borne diseases – Situation report Switzerland. www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/themen/mensch-gesundheit/uebertragbare-krankheiten/ outbreaks-epidemics-pandemics/current-outbreaks-epidemics/tick-borne-diseases.html

- Huegli D, et al.: Prospective study on the incidence of infection by Borrelia burgdorferisensu lato after tick bite in a high endemic area of Switzerland. Ticks and tick-borne diseases 2011; 2: 129-136.

- Nadelman RB, et al: Prophylaxis with single-dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme disease after an Ixodes scapularis tick bite. NEJM 2001; 345: 79-84.

- Driver H, et al: The Prevalence and Incidence of Clinical and Asymptomatic Lyme Borreliosis in a Population at Risk. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1991; 163: 305-310.

- Orasch C, et al: Lyme borreliosis in Switzerland. Schweiz Med Forum 2007; 7: 850-855.

- Evison J, et al: Evaluation and therapy of Lyme disease in adults and children. Schweiz Arzteztg 2005; 86: 2375-2384. www.sginf.ch/files/klinik_und_therapie.pdf

- Berende A, et al: Randomized Trial of Longer-Term Therapy for Symptoms Attributed to Lyme Disease. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 1209-1220.

- Nemeth J, et al: Update of the Swiss guidelines on post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. Swiss Med Wkly 2016; 146: w14353.

- Baldovin T, et al: Persistence of Immunity to Tick-Borne Encephalitis After Vaccination and Natural Infection. J Med Virol 2012; 84: 1274-1278.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(6): 38-43