At the Zurich Headache Symposium, PD Tim Jürgens, MD, Hamburg, gave insights into the diagnosis and treatment of cluster headaches. Among other things, he answered the question of why this condition is so often diagnosed only after a long delay, and went into more detail about current and new approaches in acute and long-term therapy. In particular, minimally or noninvasive neuromodulatory procedures will become even more important in the future.

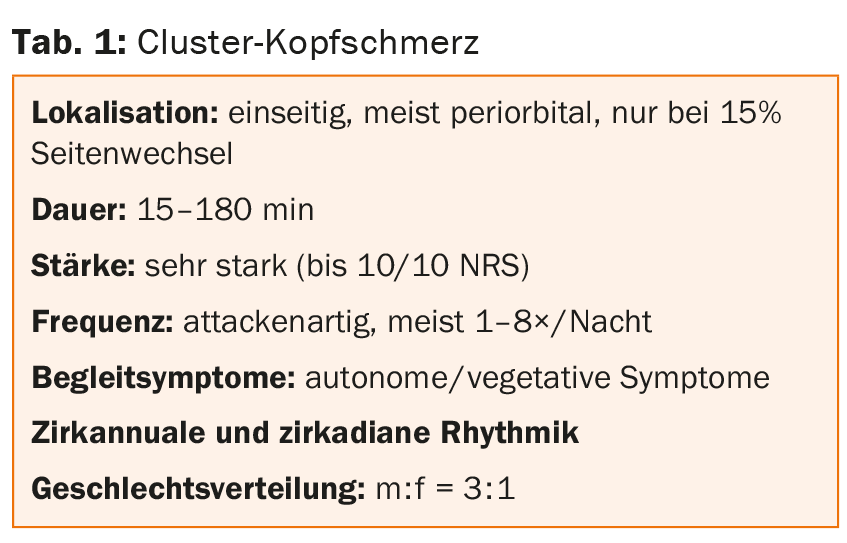

“Cluster headaches are not that rare. According to data from a Spanish specialty clinic that followed 100 patients with unilateral headache until they were diagnosed, 38 people showed this clinical picture, while, for example, only eleven were ultimately diagnosed with migraine,” says PD Dr. med. Tim Jürgens from the UKE in Hamburg. Cluster headaches (Table 1), like paroxysmal or continuous hemicranias, belong to the so-called trigeminoautonomous headaches. These are characterized by unilateral localization (emphasized V1), relatively severe intensity, and autonomic accompanying symptoms such as lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, or ear fullness. Central to distinguishing the different types of headache is the duration. Cluster pain, like tension headaches, can last for hours, while paroxysmal hemicrania – as its name suggests – usually occurs in an attack-like fashion for a few minutes. The so-called SUNCT syndrome, also belonging to the trigeminal autonomic headaches, again usually lasts only seconds and the hemicrania continua remains constant over a longer period of time.

How do cluster headaches present?

The diagnosis of cluster headache is in principle relatively simple because of the clear symptoms. Autonomic ipsilateral symptoms include a watery or red eye, runny or stuffy nose, miosis or ptosis, some permanent, eyelid edema, facial flushing or sweating, ear fullness, or restlessness to move (so-called “rocking and pacing around”). “It’s not uncommon for cluster headache to also start with a toothache,” the speaker said. “And CAVE: 3% of cases show no accompanying autonomic symptoms.”

The majority of sufferers (85%) experience headaches episodically for usually one to three months per year (peaks in spring and fall); the remaining 15% have chronic forms (less than four pain-free weeks; attacks for at least a year). In up to 70% of patients, seizures occur at fixed times of the day and year.

An important cause of delayed diagnosis is concomitant vegetative symptoms. Nausea or vomiting during attacks or photo/phonophobia lead to confusion with migraine and significant delay in diagnosis, as demonstrated in a 2003 study [1]. “To make matters worse, not only cluster headache can be accompanied by autonomic symptoms, but also migraine. In case of doubt, the duration of the attacks determines whether a migraine or a cluster headache is present,” Dr. Jürgens explained. The existence of a “cluster migraine” is debated. A questionnaire-based study from Spain with 75 patients showed a time to correct diagnosis of 4.9 years [2], a similar value had been reached by van Vliet and colleagues [1]. “There is a great need to catch up here. One possible solution is the specific training and sensitization of family physicians,” says Dr. Jürgens.

Acute therapy

Acute therapy is based on oxygen administration (“long and plenty, at least 15 minutes”), triptans, and possibly lidocaine. 100% oxygen, 7-15 l/min by mask while seated, shows good tolerability and efficacy (60% responders). Triptans such as sumatriptan s.c. (6 mg) or zolmitriptan nasal (5 mg) are also first-line agents. Both are approved for cluster headache. Contraindications include CHD, history of infarction, or pAVD.

The second choice for long attacks is sumatriptan nasal (20 mg) or zolmitriptan p.o. (5 mg) or lidocaine intranasal (1 ml 4-10%), which is inexpensive and allows a response of about 30% (also in combination with oxygen). The tip from the expert: “With triptans, use syringes if possible. They work the fastest, which is important in this indication. Oral intake is usually not enough to control attacks [3].”

Prophylaxis

For short-term prophylaxis, cortisone, at most methysergide, or again triptans such as eletriptan, zolmitriptan or frovatriptan are used. “It is important to then stop the cortisone once again,” the speaker warned.

Agent of first choice for long-term prophylaxis is verapamil (240-960 mg). The response is comparable to lithium (up to 70%), but it acts faster. It is advisable to start with 3× 80 mg, increasing at intervals of three to four days. “Always start with verapamil and don’t be afraid of high dosing,” Dr. Juergens advised.

The second choice is lithium carbonate retard (600-1500 mg with a level of 0.6-1.2 mmol/l) and topiramate. A regular laboratory with mirror control is essential. Caution is advised with topiramate (100-200 mg, increase by 25 mg every one to two weeks) regarding depression and kidney stones. Other options include capsaicin intranasally, melatonin, valproate, sartans, or gabapentin.

Newer approaches

“Placebo effects are always strong when you inject something somewhere or implant something,” Dr. Juergens elaborated. Nevertheless, in 43 patients with more than two cluster attacks per day, suboccipital steroid injection (3× cortivazole 3.75 mg within six days) reduced attack frequency significantly more than placebo in a randomized controlled trial [4].

Neuromodulatory procedures – both invasive and noninvasive – are also a new approach that has gained significant momentum in recent years. Occipital nerve stimulation, for example, according to a review by Magis et al. [5] showed at least a 50% reduction in pain frequency and/or intensity in 67% of patients with chronic cluster headache. However, it should be noted that these are not randomized controlled trials.

An exciting approach was also taken by the controlled, randomized PATHWAY CH-1 trial [6]. An implanted neurostimulator of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG), activated as needed (i.e., acute) via a device the patient holds to his cheek, showed good results: In 566 attacks (n=28), it produced pain relief/freedom after 15 minutes significantly more often than placebo. Significant differences were also seen with respect to patients whose device emitted a frequency to the stimulator that was below the perception threshold. In addition to highly significant efficacy in the acute setting, the system also reduced attack frequency. “The open-label follow-up to 24 months is promising, and the effect is stable over time. The overall response is 61% after two years,” Dr. Jürgens elaborated. “Moreover, it showed that with low-frequency programming of the device, attacks can be triggered that are treatable again with high-frequency stimulation of the SPG [7]. So we’re learning a lot from neurostimulation procedures like this.”

In addition to invasive approaches, there is a trend toward noninvasive procedures such as transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS, Nemos®, gammaCore®), transcutaneous supraorbital stimulation (tSNS, Cefaly®), or transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS).

“In the near future, we will be able to read a lot of study on this, as these procedures also seem to be effective for cluster pain,” Dr. Juergens said. For example, in the PREVA trial, 114 patients were randomized to receive either standard treatment or additional tVNS (twice daily and seizure). Data not yet published suggest a significantly greater decrease in the number of attacks per week compared with standard treatment (-6.9 vs. -2.0; p=0.0025).

The psyche also suffers

Psychiatric comorbidities incl. suicidal thoughts should always be inquired about and taken very seriously. They are common in patients with cluster headaches. Therefore, both the headache and the comorbidities must be treated consistently. The treatment of choice is lithium, and additive antidepressants (amitriptyline, SSRIs, and with limitations SSNRIs). Topiramate should be avoided in this case.

Source: Zurich Headache Symposium, August 27, 2015, Zurich.

Literature:

- van Vliet JA, et al: Features involved in the diagnostic delay of cluster headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003 Aug; 74(8): 1123-1125.

- Sánchez Del Rio M, et al: Errors in recognition and management are still frequent in patients with cluster headache. Eur Neurol 2014; 72(3-4): 209-212.

- Law S, Derry S, Moore RA: Triptans for acute cluster headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013 Jul 17; 7: CD008042.

- Leroux E, et al: Suboccipital steroid injections for transitional treatment of patients with more than two cluster headache attacks per day: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2011 Oct; 10(10): 891-897.

- Magis D, Schoenen J: Advances and challenges in neurostimulation for headaches. Lancet Neurol 2012 Aug; 11(8): 708-719.

- Schoenen J, et al: Stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) for cluster headache treatment. Pathway CH-1: a randomized, sham-controlled study. Cephalalgia 2013 Jul; 33(10): 816-830.

- Schytz HW, et al: Experimental activation of the sphenopalatine ganglion provokes cluster-like attacks in humans. Cephalalgia 2013 Jul; 33(10): 831-841.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(6): 36-39.