On the third day of this year’s EULAR Congress, news was presented in the areas of fibromyalgia, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and osteoarthritis. Experts from four different countries presented current findings on the pathogenesis, diagnostic strategies and forms of therapy for these four rheumatic diseases.

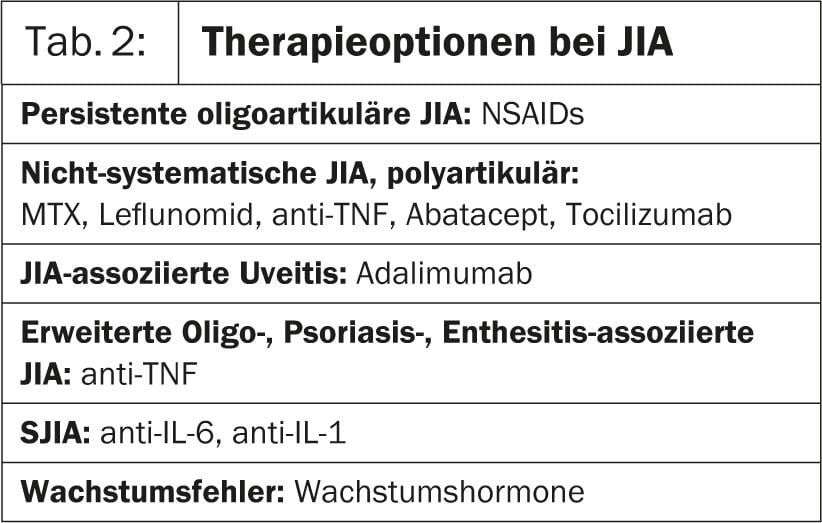

In the first presentation of Hot Session 6, Prof. José António P. da Silva, MD, Portugal, went into more detail about fibromyalgia. Research shows that changes in the central nervous system are the reason for the condition. As a result, the brain processes pain signals incorrectly, resulting in an intensifying sensation of pain. In patients with fibromyalgia, therefore, it takes a much weaker stimulus than in healthy individuals to elicit pain [1]. “In the management of this disease, the same rules apply to physicians as to all chronic conditions(Table 1).

You have to:

- conduct a comprehensive investigation

- educate yourself further

- Set clear therapy goals

- find multimodal treatment pathways, i.e. pharmacological but also non-pharmacological

- Closely monitor response to therapy and progress or setbacks.

- draw conclusions from this for the redefinition of the therapy.

The physician must also show that he approaches the patient’s individual experience of illness with an open mind and without prejudice, and that he really takes the patient’s pain seriously,” says Prof. da Silva. According to his own assessment, fibromyalgia is stress-induced, resulting in muscle tension and muscle pain. Therefore, it is important to precisely ask the patient’s expectations and to evaluate realistic therapy goals in cooperation so that as little additional stress as possible arises from the therapy [2].

Pregabalin 450 mg/d has been shown to be effective in studies (pain relief: 46.9% vs. placebo: 31.5%), but accompanied by various side effects such as dizziness, fatigue, dry mouth, weight gain, and peripheral edema. One in four patients stopped therapy because of this (NNH: 6) [3]. Duloxetine and milnacipran offer little benefit in pain relief. It also does not substantially improve sleep problems, fatigue, and quality of life (QOL) compared with placebo [4].

Because depression is common as a comorbidity in fibromyalgia, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline may also be effective. Houses et al. (2012) showed pain relief with minor side effects with antidepressant therapy in a small group of patients. However, a remarkable number of participants stopped therapy precisely because of the poor effect/side effect balance [5].

“As a non-pharmacological alternative, for example, “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy” (CBT) can be considered, which also relieves pain and reduces depression [6],” Prof. da Silva said.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Next, Pierre Quartier, MD, Paris, spoke about juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). “There are several subtypes: systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (also known as Still’s disease), juvenile polyarthritis, oligoarthritis, as well as psoriatic arthritis and others. In any case, the onset of this disease is before the age of 16,” Dr. Quartier said. Systemic JIA (SJIA), for example, is a particularly severe form of childhood rheumatoid arthritis. Criteria include onset <16 years, duration >6 weeks, no differential diagnosis, fever ≥15 days, and one or more of the following: Rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, inflammation of serous membranes.

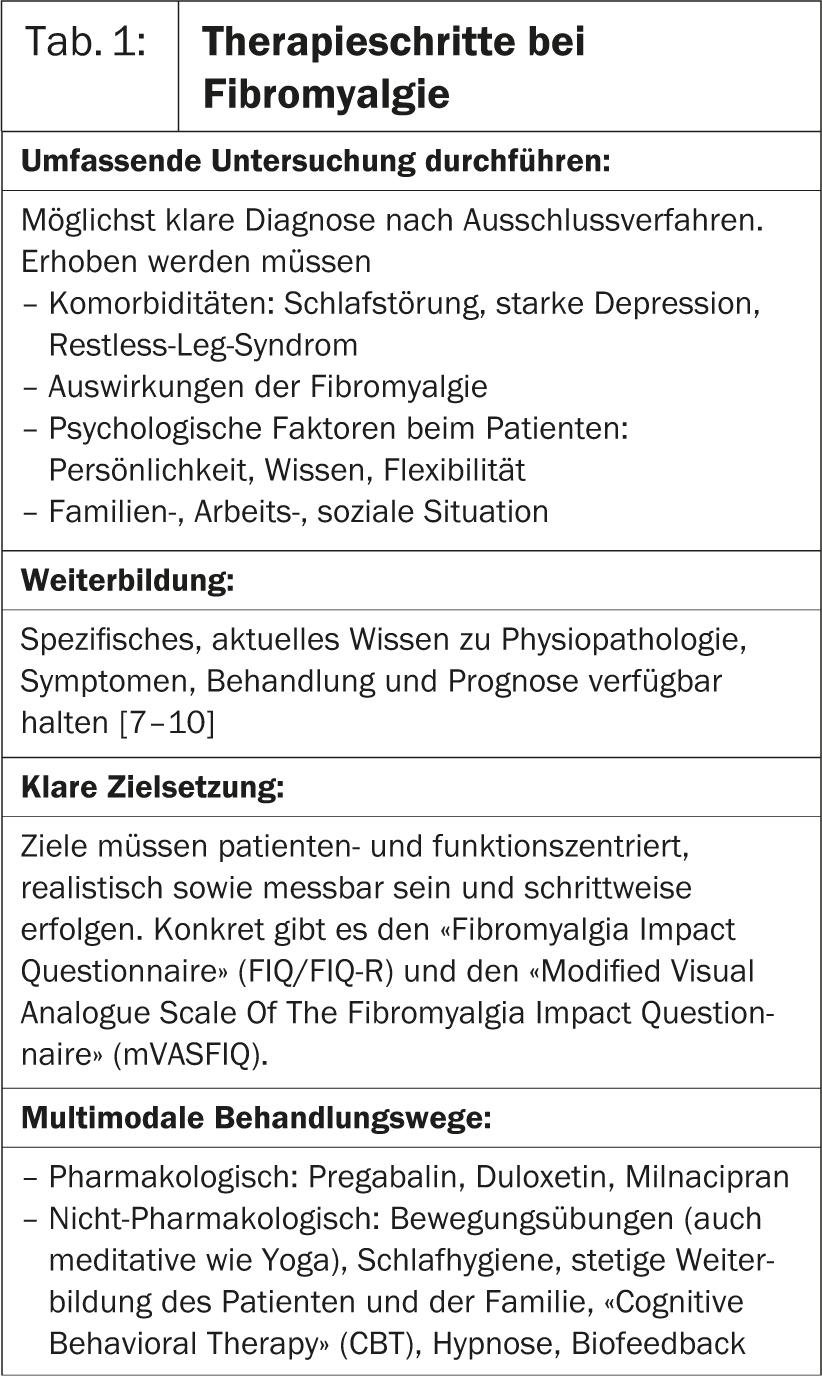

“In any case, a pediatric rheumatologist must work in a multidisciplinary team. This means that the child’s parents, family doctor, caregivers from school or daycare, etc. must be closely involved in the therapy. If possible, non-aggressive treatment is recommended. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), joint injections (corticosteroids), physiotherapy and various other forms of care are used,” says Dr. Quartier. “Numerous clinical trials of drug options for forms of JIA are currently underway(Table 2). Overall, JIA treatment can be considered a work-in-process.”

Psoriatic Arthritis

“What’s new in psoriatic arthritis?” This question was answered in the lecture by Juan J. Gomez-Reino, MD, Santiago. Recent studies corroborate the evidence that there is an association between high BMI (obesity) and the development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in patients with confirmed psoriasis [11, 12]. In addition, smoking has been confirmed as an important risk factor for psoriasis [13].

Regarding the diagnostic tools in early PsA, the “CASPAR-Study-Group” criteria are shown to be more sensitive than the Moll and Wright criteria [14]. Moreover, imaging by MRI and ultrasound (US) is becoming increasingly important in PsA. They increase the understanding of this disease and thus contribute to better diagnosis and control of treatment. The newly developed PsAMRI score is already being used for randomized controlled trials. It is very suitable for objective measurement of disease activity. “Whole-body multi-joint” MRI (WBMJ-MRI) provides a kind of snapshot of inflammation in the affected joints in PsA [15]” Dr. Gomez-Reino explained. “Furthermore, MRI can help differentiate rheumatoid arthritis from PsA. This is especially true in selected patients in whom conventional clinical, laboratory and radiographic examinations did not yield clear results.”

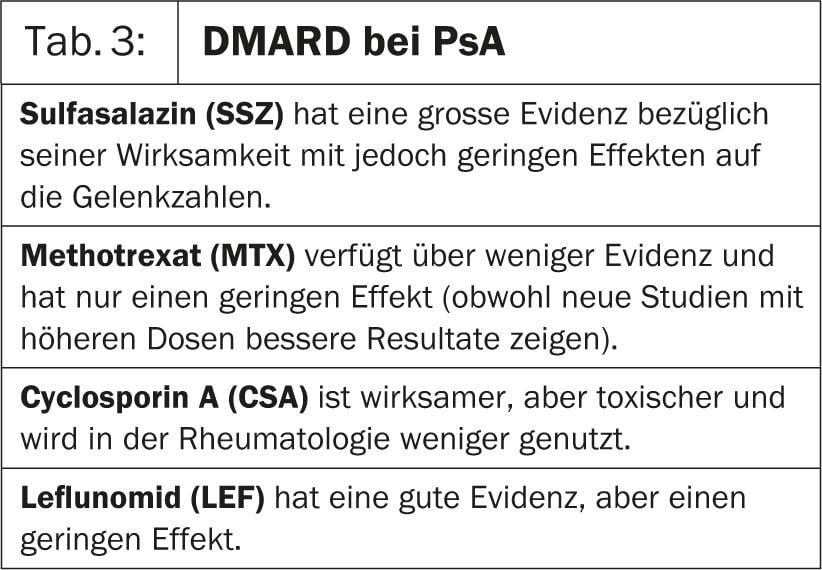

In treatment, different degrees of effectiveness and evidence of traditional-

disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs); they are summarized in Table 3.

Overall, according to Dr. Gomez-Reino, the following points emerge that are relevant to practice:

- Newly identified pathogenetic pathways are emerging as therapeutic targets in PsA.

- Obesity and smoking are reversible risk factors for PsA and for response to therapy.

- US and MRI have great potential for PsA diagnosis.

- The oral PDE-4 inhibitor apremilast and possibly biologics that interfere with the IL-23/IL-17 pathway may provide an alternative in the treatment of PsA patients in whom TNF inhibitors are insufficiently effective.

- Cardiovascular risk factors (dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, smoking) are more prevalent in PsA patients than in controls [16].

Osteoarthritis

According to Prof. Margreet Kloppenburg, Leiden, MD, two topics are of particular interest at the moment:

- The role of subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: The cytokine signaling molecule transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) in subchondral bone may represent a potential therapeutic target.

- The non-pharmacological therapy. In treatment, physical therapy in particular can be effective. However, only certain forms of it, as shown in a meta-analysis by Wang et al. (2012) shows: Aerobic and water exercise reduced disability. Aerobic and strength exercises and ultrasonography reduced pain and improved function. Thus, one form of therapy alone could not improve all limitations simultaneously. Diathermy, orthopedics, and magnetic stimulation were ineffective [17].

“We are still in the process of understanding this disease” said Prof. Kloppenburg. “For example, bone mineral density (BMD) is associated with the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: A change in systemic BMD is associated with disease progression. The role of bone also needs to be examined more closely. A recent study shows that giving bisphosphonates can reduce pain [18].”

Other current desiderata concern new diagnostic strategies. According to Prof. Kloppenburg, MRI is not suitable for clinical practice because the vast majority of individuals who do not show radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis show lesions in the middle and older stages of life [19].

“In therapy, strontium ranelate, actually an osteoporosis drug, has also been shown to be effective. A post-hoc analysis of an osteoporosis trial shows that strontium ranelate was able to reduce radiographic progression and back pain in spinal osteoarthritis vs. placebo [20]. Similar results exist for knee osteoarthritis. Overall, the drug was well tolerated [21]”, explained Prof. Kloppenburg.

Source: EULAR, 12-15 June 2013, Madrid

Literature:

- Fibro Collaborative: Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87: 488.

- Paiva, Jones: Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010; 24: 341-352.

- Tzellos, et al: J Clin Pharm Ther 2010 Dec; 35(6): 639-56.

- Hauser, et al: The Cochrane Library January 31, 2013.

- Houses, et al: CNS Drugs 2012; 26(4): 297-307.

- Bernardy, et al: J Rheumatol 2010 Oct; 37(10): 1991-2005.

- Burckhardt, et al: J Rheumatol 1994; 21: 714-720.

- King, et al: J Rheumatol 2002; 29: 2620-2627.

- Rooks, et al: Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 2192-2200.

- White, et al: Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47: 260-265.

- Wenqing, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71: 1267-1272.

- Jon Love, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71(8): 1273-1277.

- Li, et al: American Journal of Epidemiology 2011; 175(5): 402-413.

- Coates, et al: Arthritis Rheum 2012 Oct; 64(10): 3150-5.

- Coates, et al: Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012; 26(6): 805-22.

- Jamnitski, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 211-216.

- Wang, et al: Ann Intern Med 2012 Nov 6; 157(9): 632-44.

- Laslett, et al: Ann Rheum Dis. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202989.

- Guermazi, et al: BMJ 2012; 345. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5339 (Published August 29, 2012).

- Bruyere, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 335-339.

- Reginster, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 179-186.