The risk of recurrence in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis is less than anticipated, and a second episode of acute diverticulitis is not an obligatory indication for resection. Sonography is an effective examination that is not stressful for the patient and in many cases eliminates the need for computed tomography. Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis can be treated on an outpatient basis in otherwise healthy patients, even without antibiotics. Colonoscopy should be avoided during acute diverticulitis. After the diverticulitis has healed, usually after about six weeks, colonoscopy should be performed. Patients with complicated diverticulitis should be hospitalized.

New insights into the pathogenesis, therapy, and natural history of diverticulosis have led to relevant changes in the treatment strategy of this common disease. The value of antibiotic therapy is questionable in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Even a second episode of diverticulitis is now no longer an indication for resection. Outpatient therapies are possible if the patient is in good general condition without relevant comorbidity. These and other new aspects of diverticular disease relevant to practice are highlighted and explained in the following article.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Diverticulosis is a very common disease, with prevalence showing strong geographic variation and a striking increase with age. In the Western world, where the disease is particularly common, it is rarely found in those under 40 years of age (less than 5%). The prevalence increases steadily with age: in the 70-year-olds, the prevalence is thought to be as high as 65%.

The mechanisms underlying the development of diverticula have not been elucidated in detail, but are likely to correspond to a complex interplay of genetics, colonic motility (neural degeneration of cells in the myenteric plexus and Cajal cells), nutritional factors, microbiome, and inflammatory processes. In the development of diverticulitis, fecal stasis, local bacterial overgrowth, reduced perfusion in the area of the vasa recta, and finally microperforation play a pathogenetic role. Whether acute uncomplicated or complicated diverticulitis develops depends largely on local and systemic defense factors of the patient.

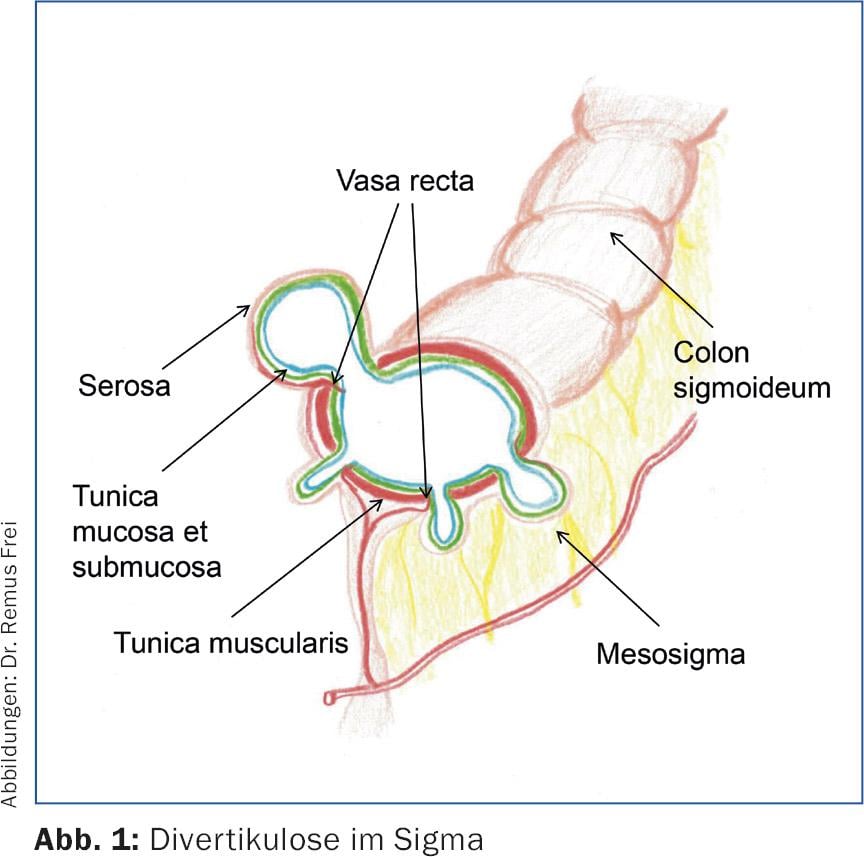

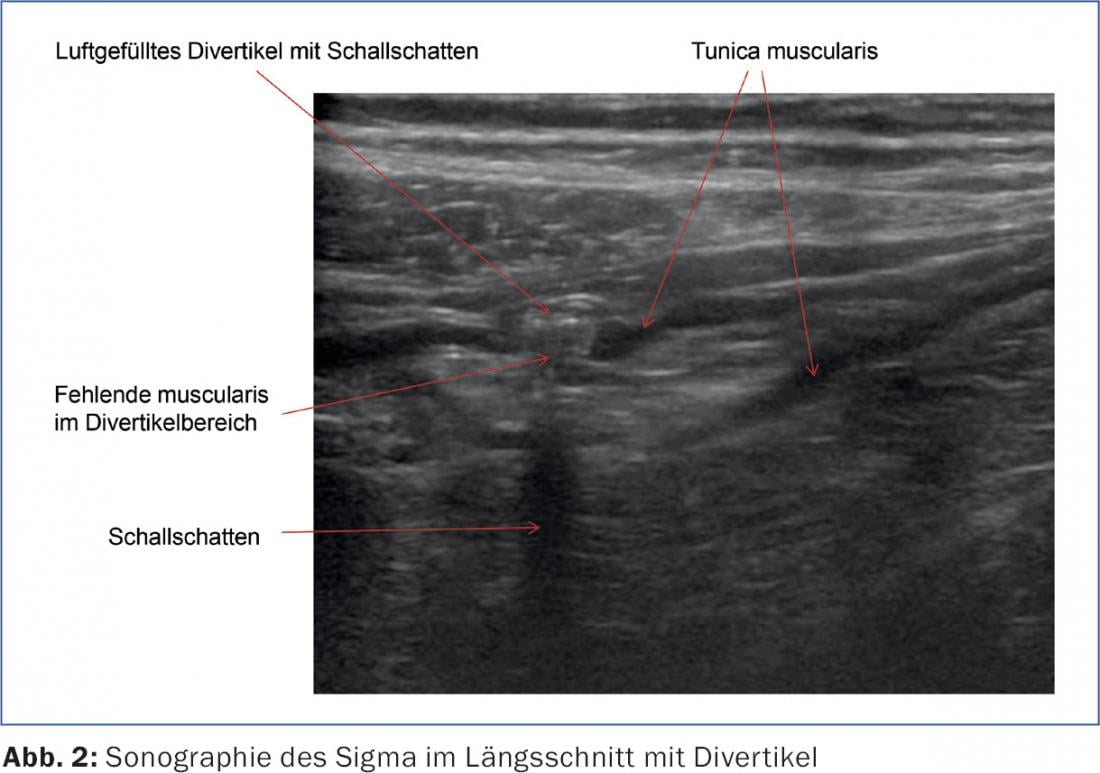

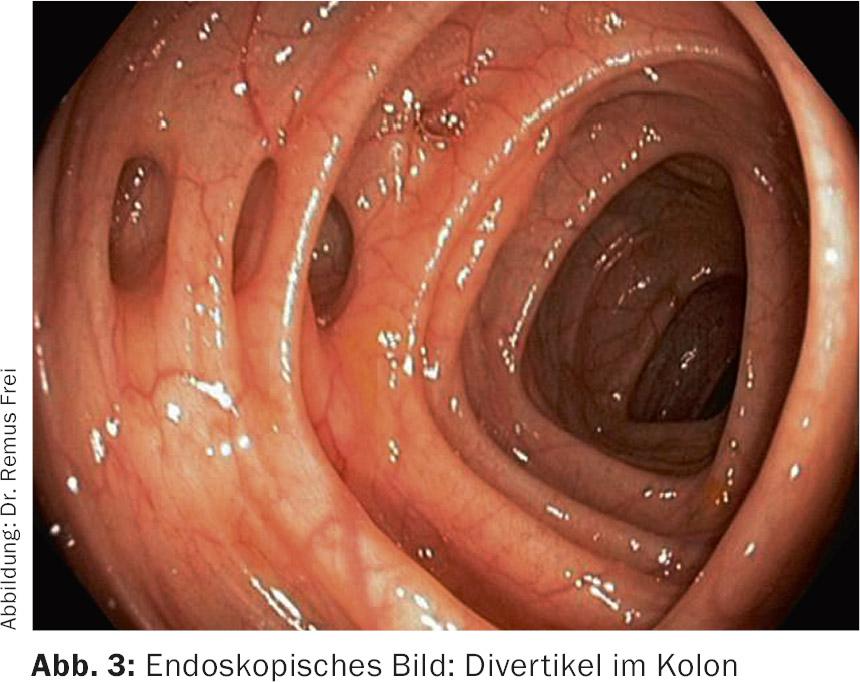

Diverticula of the left-sided colon are “pseudodiverticula”, because only mucosa and submucosa bulge through muscle gaps in the area of the passing vasa recta (Fig.1 and 2). These pseudodiverticula usually occur accentuated in the sigmoid colon, which is known as the “high-pressure zone” of the colon (Fig.3). Diverticula on the right side of the colon are true diverticula because the entire wall of the colon bulges out here. This entity is observed mainly in the Asian region and is a rarity in the Western world. Colonoscopic studies from Japan show a prevalence of right-sided diverticula of 21.6% [1].

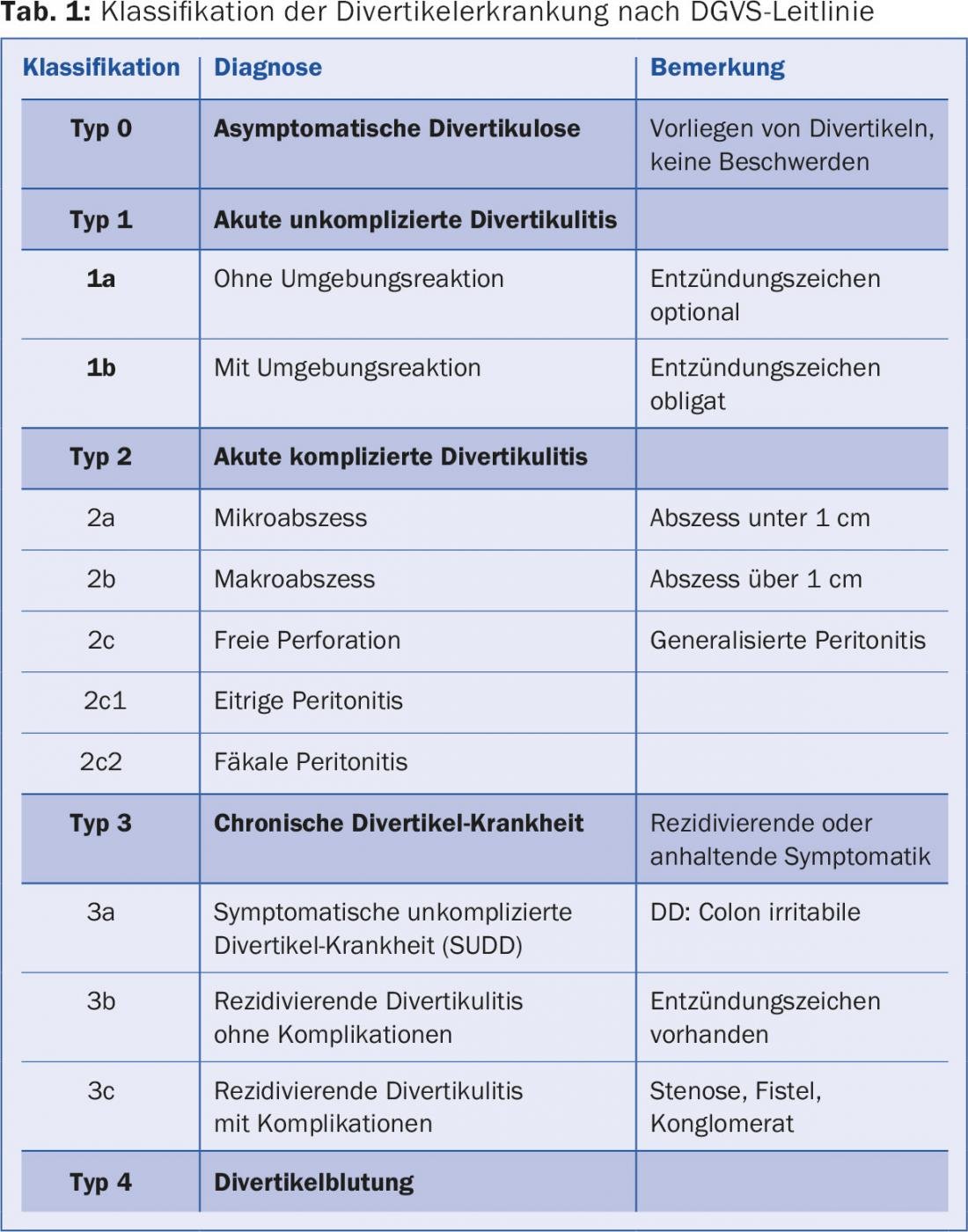

The spectrum of the disease ranges from asymptomatic diverticulosis to acute diverticulitis (uncomplicated and complicated) to chronic diverticular disease (with the classic complications of fistulas, stenoses, and conglomerate tumor) to diverticular hemorrhage. The entire spectrum of disease is well represented in the current guideline of the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) (Tab. 1).

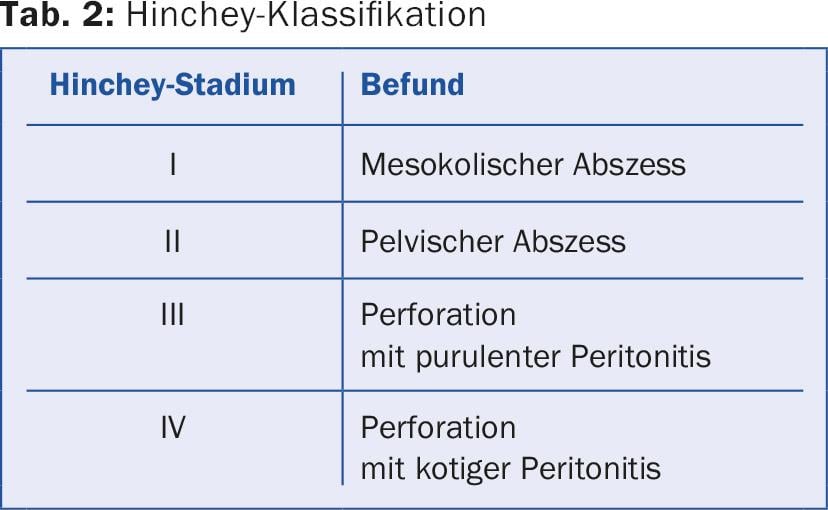

A new concept is symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD, type 3a), a clinical picture that shows overlaps with and is difficult to differentiate from irritable colon. The disease is also associated with increased visceral sensitivity. Another rare entity (approximately 1%, male predominance) is so-called SCAD (segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis), which manifests with pain and hematochezia and histologically resembles inflammatory bowel disease. Primarily from a surgical standpoint, the Hinchey classification is still used, which further classifies complicated diverticulitis and defines the surgical approach (Table 2).

Natural course of the disease

While about 75% of patients with diverticulosis remain symptom-free, about 25% develop symptomatic disease. Risk factors for developing diverticulitis include obesity, smoking, NSAID use, steroid therapy, and opiates. The occurrence of diverticulitis is a rarer event than previously thought. The study of more than 2000 patients with endoscopically proven diverticulosis showed in the follow-up over eleven years that only just over 4% of patients experience diverticulitis, with a median time to onset of seven years [2].

Younger patients with diverticulosis have a higher risk of developing diverticulitis, with a 24% lower risk of diverticulitis per decade of life [3].

The risk of recurrence after conservatively treated diverticulitis is also lower than previously thought. We now estimate that the risk for a first recurrence is about 13% and for a second recurrence about 4%.

In summary, recurrences after diverticulitis are basically not frequent, complicated recurrence after uncomplicated diverticulitis is rare (<5%), two or more recurrences do not increase the risk of complications, and chronic symptoms persist in approximately one fifth of patients even after resection [4]. These recent findings have essentially led to the strategy of performing resection after a second episode of diverticulitis being largely abandoned. The situation is different after complicated diverticulitis; here the risk of recurrence is up to 50%, depending on the study, and resection “a froid” is usually recommended.

Diagnostics in acute diverticulitis: CT not always necessary

The first priority in diagnosis is history and clinical examination (abdominal examination and rectal examination). Laboratory chemistry should include a blood count, CRP, and urinalysis as a minimal program. Clinical diagnosis of diverticulitis based on history, laboratory, and examination is not reliable. Sensitivity is low at approximately 60-70% depending on the work considered [5].

Abdominal ultrasonography has established itself as a simple, widely available examination that is not burdensome for the patient (Fig. 3). In the diagnosis of diverticulitis, ultrasonography is practically equal to computed tomography and, in meta-analyses, achieves a sensitivity and a specificity of a good 90% each [6]. Computed tomography may offer diagnostic advantages in cases of special localization (deep sigmoid diverticulitis) and distance abscesses, as well as in unclear clinical situations.

Colonoscopy is not necessary for diagnosis and should be avoided whenever possible during acute diverticulitis because of a possible increased rate of perforation. In unclear situations, especially if malignancy is suspected, endoscopic clarification can be performed in exceptional cases, even in the acute stage, if computed tomography has ruled out a covered perforation. We then recommend a very careful endoscopy with a thin instrument up to the corresponding pathology without passing it.

Therapy of uncomplicated diverticulitis

Uncomplicated diverticulitis, i.e., without evidence of an abscess, can be treated as an outpatient in an otherwise healthy patient who is able to eat orally. New studies have shown that antibiotic therapy can also be dispensed with – previously a standard of care in the treatment of acute diverticulitis. In a Swedish study of over 600 patients, no differences were found regarding complications (abscess, perforation, resection, recurrence), regardless of whether antibiotic therapy was given or not [7]. This work is often cited as a landmark for this new strategy of diverticulitis therapy. It should be noted that only patients without relevant comorbidity or immunosuppression were included in this study.

Therapy of complicated diverticulitis

If a peridiverticulitic abscess (complicated diverticulitis) is found, inpatient therapy is recommended. Antibiotic therapy is still the standard of care here. In the case of an abscess with a size below 3-4 cm (Hinchey I), drainage can usually be dispensed with: In small series, there was no difference in outcome when antibiotic therapy alone or antibiotic therapy with additional drainage was used [8]. In the case of an abscess larger than approx. 4 cm, drainage should be performed in addition to antibiotic therapy. This can be inserted CT or also sonographically controlled. There are no prospective or randomized data for this therapy concept, which is frequently used and successful in the clinic.

Patients who have free perforation with peritonitis should be operated on after diagnosis. If possible, the operation (sigmoid resection) is performed laparoscopically under primary continuity establishment with insertion of a protective double-barrel ileostomy. In septic and unstable patients, Hartmann surgery is performed (sigmoid resection, rectal closure, descendostomy) with secondary restoration of continuity.

The value of laparoscopic peritoneal lavage and drainage without resection (for perforated diverticulitis and purulent peritonitis, Hinchey III) remains incompletely understood. In the current DGVS guideline, it is mentioned as a therapeutic option, and individual use is considered justified [9]. However, based on the current data, it remains unclear which patients will benefit from this procedure and whether resection will be necessary after all. Clinically relevant stenoses as well as fistulas (colo-vesical, colo-vaginal, colo-cutaneous) and conglomerate tumors usually represent clear surgical indications.

Procedure after diverticulitis

The recurrence rate after acute diverticulitis depends on its severity. After acute uncomplicated diverticulitis and even after its recurrence, resection is not necessary. After complicated diverticulitis, the risk of recurrence is high, so sigmoid resection should be discussed with the patient. Colonoscopy after healing of diverticulitis is recommended in principle (usually after 4-6 weeks), although the data for this is rather thin [10]. In principle, the aim is to confirm the diagnosis and exclude other pathologies, especially malignancy.

Unfortunately, there is no proven strategy to prevent diverticulitis recurrence. Despite the lack of a clear data base, the intake of a high-fiber diet is generally recommended. Mesalazine, probiotics, and rifaximin (a nonabsorbable antibiotic) have no protective effect and generally should not be prescribed [11].

Literature:

- Yamada E, et al: Association between the location of diverticular disease and the irritable bowel syndrome: a multicentre study in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109(12): 1900-1905.

- Shahedi K, et al: Long-term risk of acute diverticulitis among patients with incidental diverticulosis found during colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11(12): 1609-1613.

- Strate LL, et al: Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(10): 1486-1493.

- Regenbogen SE, et al: Surgery for diverticulitis in the 21st century: a systematic review. JAMA Surg 2014; 149(3): 292-303.

- Schwerk WB, et al: Sonography in acute colonic diverticulitis. A prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum 1992; 35(11): 1077-1184.

- Lameris W, et al: Graded compression ultrasonography and computed tomography in acute colonic diverticulitis. Eur Radiol 2008; 18(11): 2498-2511.

- Chabok A, et al: Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surgery 2012; 99(4): 532-539.

- Brandt et al: Percutaneous CT scan-guided drainage vs. antibiotherapy alone for Hinchey II diverticulitis: a case control study. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; 49(10): 1533-1538.

- S2k guideline of diverticular disease/diverticulitis. German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases, DGVS, 2014.

- De Vries HS, et al: Routine colonoscopy is not required in uncomplicated diverticulitis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc 2014; 28(7): 2039-2047.

- Tursi A: Preventing recurrent acute diverticulitis with pharmacological therapies. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2013; 4(6): 277-286.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(9): 14-19