Tinnitus is defined as the perception of sounds, such as whistling, buzzing, booming, hissing, or hissing, to which no external sound source can be attributed. Acoustic hallucinations, which can occur in certain psychiatric disorders and/or in the context of substance use, are to be distinguished from tinnitus.

Tinnitus (from Latin tinnire; “to ring”) is defined as the perception of sounds such as whistling, buzzing, booming, hissing, or hissing to which no external sound source can be attributed. Acoustic hallucinations, which can occur in certain psychiatric disorders and/or in the context of substance use, are to be distinguished from tinnitus. Auditory hallucinations involve voices or complex sounds (e.g., music), whereas tinnitus involves sounds devoid of content.

One speaks of a chronic tinnitus from a duration of three months. In everyday life, however, the degree of compensation is more decisive. In the case of compensated tinnitus, the affected persons are not or only slightly affected by the noise in everyday life, whereas persons with decompensated tinnitus often experience a more severe disease burden.

Further, a subjective tinnitus is distinguished from an objective tinnitus. In the much rarer objective tinnitus, the sound originates from an endogenous noise source (“body sounds”), such as flow sounds from vessels near the ear or spasms in the internal muscles of the middle ear or the palatal muscles [1,2].

Epidemiology

About 15% of people are affected by tinnitus in the course of their lives [3]. Results from epidemiological studies show similar prevalences not only in different European countries, but also in the USA, Japan, and also in low-income countries in Africa and Asia [1].

The prevalence of decompensated tinnitus is about 1-2% of the total population and is often accompanied by sleep problems, concentration disorders and/or depression [1,2,10].

Risk factors

The main risk factors for the occurrence of tinnitus include older age, male gender, and hearing loss. Further promoting factors are noise exposure, psychiatric concomitant diseases, craniocerebral trauma, middle or inner ear infections, and ototoxic drugs that can damage hearing, such as antibiotics (especially gentamicin), loop diuretics, or platinum-containing chemotherapeutic agents [4].

Pathophysiology

In principle, any temporary or permanent hearing loss can cause tinnitus. Thus, tinnitus can develop along the entire auditory pathway. The most common site of origin is thought to be in the cochlea, where damage and degeneration of hair cells occurs, resulting in sensorineural hearing loss. Other causes of conductive dysfunction may include cerumen, otitis media acuta or chronica, or otosclerosis. As a result, compensatory neuronal activity may occur along the central auditory pathway and auditory cortex. Changes in the auditory nerve, such as in vestibular schwannoma, or microvascular changes can lead to retrocochlear hearing loss and likewise tinnitus. Since not every hearing loss must automatically lead to tinnitus, it is important for the perception of compensatory activity as tinnitus that a neuronal connection to other areas of the brain, which are responsible for attention, consciousness, stress, emotion, or memory, for example, is established. Depending on the inclusion of the networks described, this model-like conception can then also be used to explain the varying extent to which people are personally affected. Thus, the occurrence of tinnitus can also be explained in connection with emotional factors, stress or a psychiatric illness. There is no direct correlation between the degree of hearing loss and the perceived loudness of an ear noise. It may not be possible to detect hearing loss in conventional hearing tests [5]. In this constellation, it is assumed that so-called “cochlear dead regions” or synaptopathies between the individual neurons of the auditory system are responsible for the tinnitus-causing imbalance in the auditory system as harbingers of a future hearing impairment [6].

In addition to damage to the cochlea or auditory pathway, tinnitus is also more commonly observed with temporomandibular dysfunction/bruxism or cervical spine and neck conditions. Furthermore, movements in the area of the described joints can also lead to a modulation of ear noises (higher, lower, louder, quieter). This is thought to be caused by (afferent) somatosensory input from the trigeminal nerve and C2 fibers to central auditory pathway activity via interactions at the dorsal cochlear nucleus at the brainstem level [15]. If the tinnitus perception or the tinnitus change due to manipulation in the somatosensory area is in the foreground of the complaints, one also speaks of a “somatosensory tinnitus”.

Often the occurrence of tinnitus is multifactorial. Thus, abnormal auditory or somatosensory inputs together with altered activity in central nervous structures (e.g., after traumatic or ischemic lesion or emotional factors) or the combination of these can lead to tinnitus development and persistence. Especially in traumatic head injuries, this can be the cause.

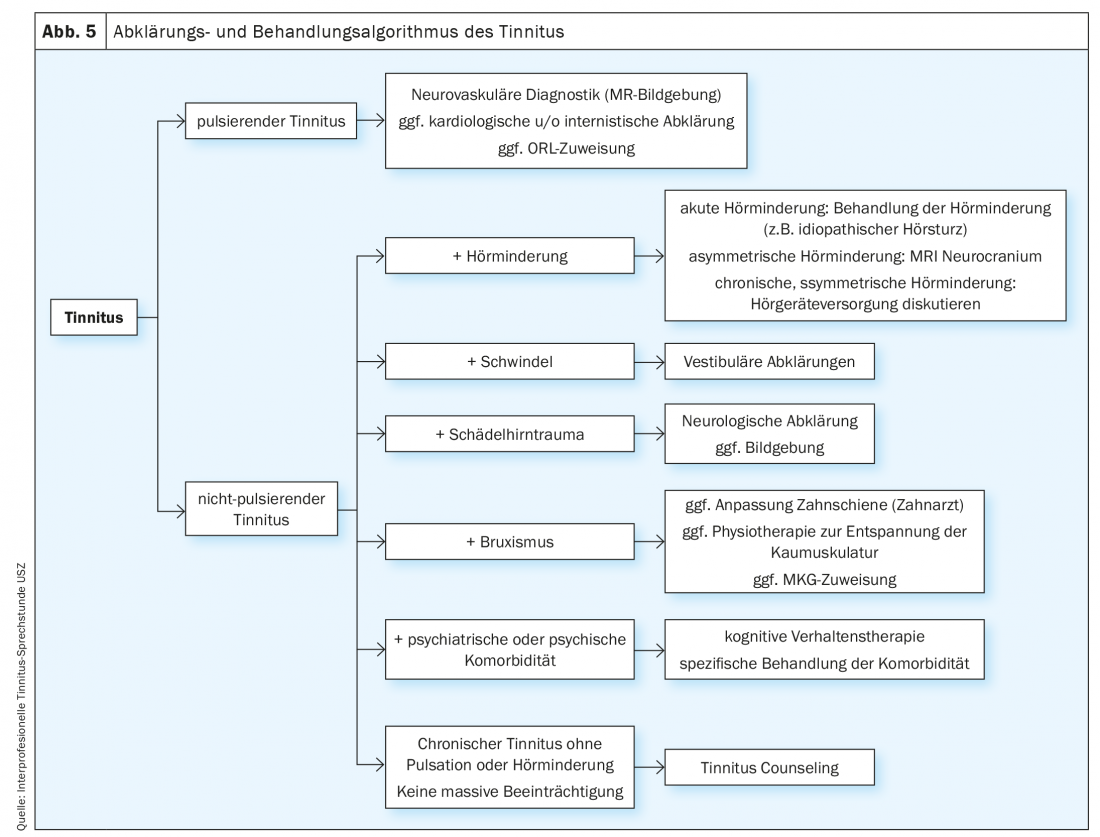

A “subjective” tinnitus is distinguished from an “objective” tinnitus (Fig. 1) . In the latter case, the origin of the noise can sometimes be traced by clinical examination and often the source of origin can be found.

In objective tinnitus, different causes may be present. If a pulse-synchronous tinnitus is found, vascular abnormalities such as vascular stenosis or dissection, arteriovenous fistulae, glomus tumors, increased blood flow (for example, in the setting of anemia), or caliber changes of the sigmoid sinus may be present. Other causes of objective tinnitus may include palatal myoclonus or middle ear myoclonus (tensor tympani muscle, stapedius muscle), nasal or parapharyngeal space-occupying lesions with consecutive tube ventilation disturbance, or spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. Treating the cause of objective tinnitus can in some cases lead to complete disappearance of the tinnitus.

Diagnostics and necessary clarifications

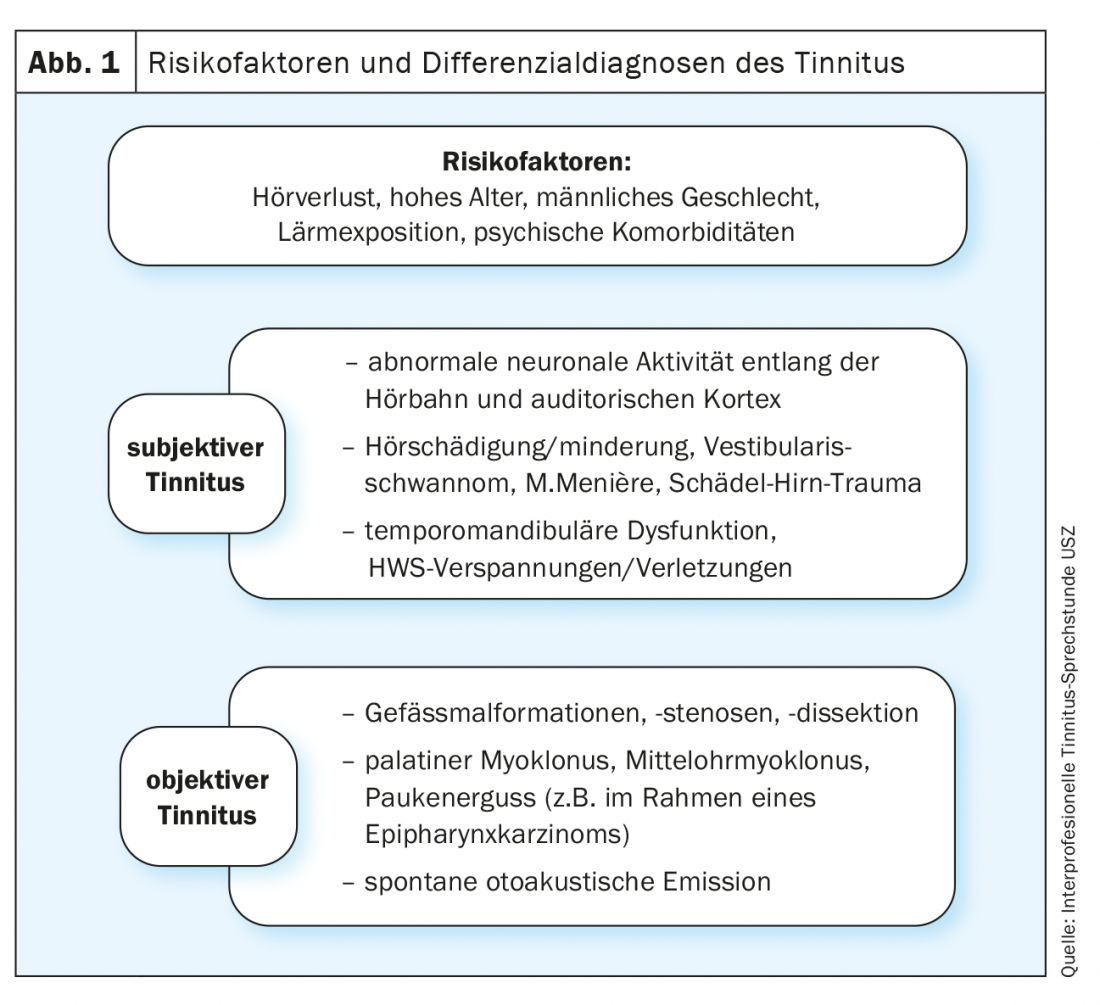

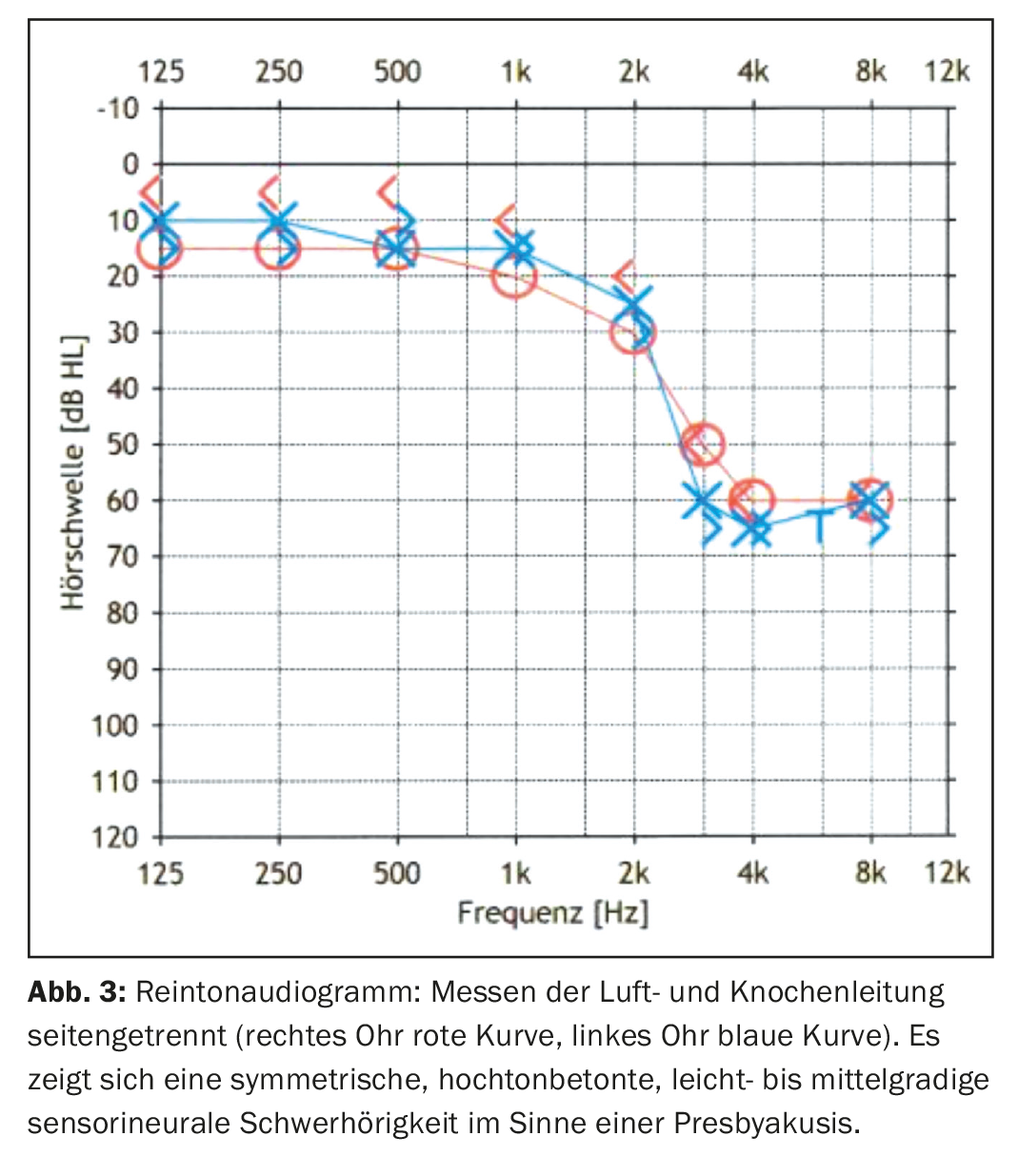

Any new onset of tinnitus that persists for several days to weeks should be clarified by means of a detailed history and clinical examination. It is important to recognize special cases and to initiate further diagnostics in these situations (Fig. 2). The first contact with a tinnitus sufferer often takes place at the family doctor or ORL physician. This consultation represents a great importance in the desensitization of the patient. It is essential that the patient is taken seriously and that the fears and uncertainties caused by the tinnitus can be intercepted by attentive listening and explanation. Standardized questionnaires can be used to assess the perception of tinnitus and the associated distress, which ultimately influences further treatment steps. Tinnitus counseling is also of great importance, as it aims to prevent sensitization and thus reduce the risk of tinnitus becoming chronic. The patient should be encouraged to try to tune out the noise by means of relaxation exercises, defocusing, quiet background music, etc. Every clinical examination includes otological and audiological diagnostics as well as examination of the cervical spine and temporomandibular joint. If there is a suspicion of pathology on ear microscopy, further investigations are indicated. Similarly, if the hearing curve is asymmetric, if the dynamics of hearing deterioration are rapid or acute, or if there are comorbidities such as vertigo, further steps should be taken. The treatment of patients with chronic tinnitus requires an interdisciplinary approach, especially in cases of high suffering.

Case study

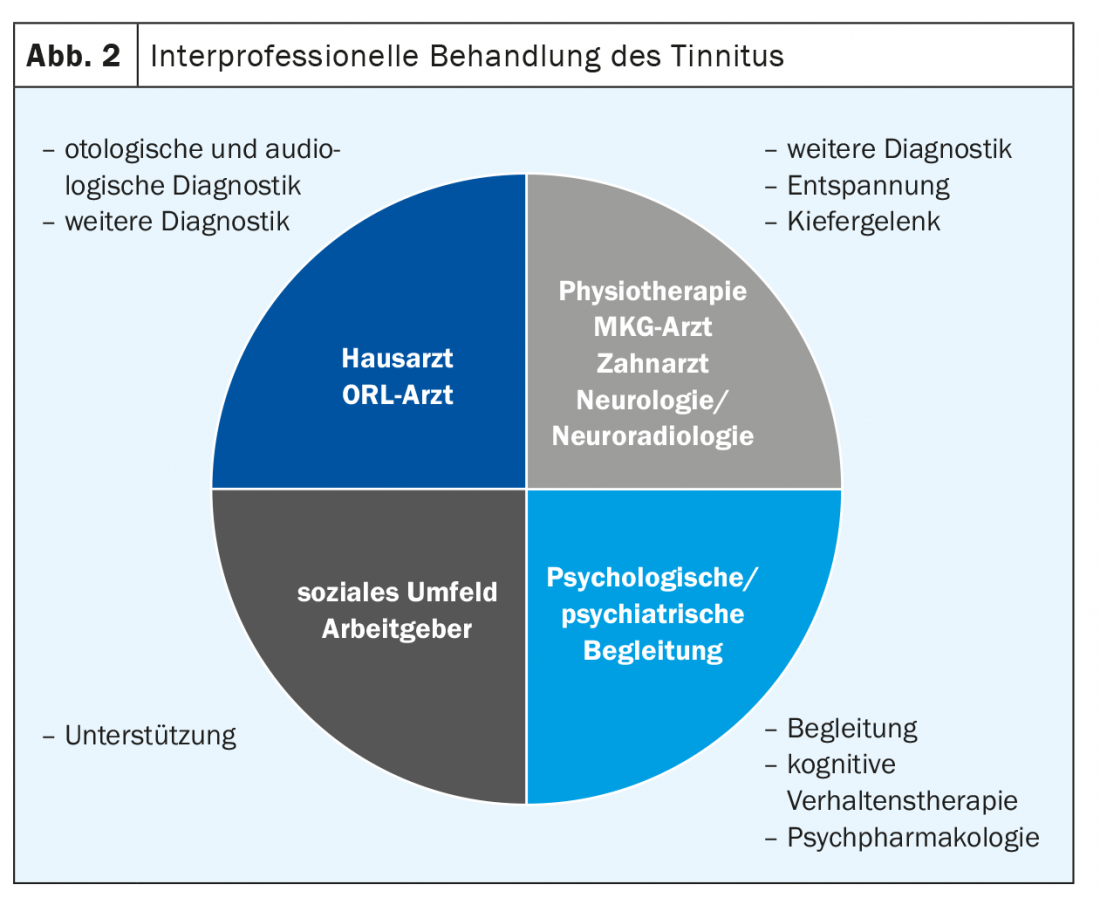

Using a fictitious example, we will illustrate the diagnostic algorithm of a typical patient in the tinnitus consultation of the University Hospital Zurich: Mr. M. (67 years old) has been suffering from tinnitus for about 5 years. Because of this, he has already visited his family doctor several times, who could not determine a clear cause for the tinnitus. In cases of high distress, referral to a center was made. In the consultation, in addition to a detailed history on the quality and quantity of the tinnitus and its impact on the patient’s life, other specific points were inquired about, such as a detailed ear history (vertigo, hearing loss, pain, otorrhea), trigger factors, temporal correlations, and indications for somatosensory tinnitus (connection with complaints in the cervical spine, temporomandibular joints, or masticatory muscles). Furthermore, a clinical examination in terms of a tuning fork examination (Weber and Rinne test), an ear microscopy and a complete ORL status were performed. This served to exclude a specific/objective cause of tinnitus. Audiological tests included a standard pure tone audiogram (125-8000 Hz) (Fig. 3), a high tone audiogram (9-20 kHz) (Fig. 4) , and a tinnitus determination. Further, the level of suffering was systematically assessed in the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) [11]. A detailed explanation of the pathophysiology of the tinnitus is then given and an individualized interprofessional, patient-based therapy is proposed.

In the tinnitus determination, the patient indicates which frequency corresponds to his tinnitus after various tones and sounds are played to him. The result is recorded and marked with a T. In this case, the patient hears a sinus tone “in the middle”, i.e. symmetrically in both ears. At 6300 Hz, the tinnitus overlaps with the played frequency. Often the tinnitus frequency is in the range of the greatest hearing loss.

Therapy

On the one hand, the management of tinnitus includes an empathic-validating conversation, taking into account the patient-specific circumstances, concerns and fears. In most cases, causal therapy is not possible. Thus, education and discussion of coping strategies (tinnitus counseling) are among the most important points of therapy. If this is not sufficient, behavioral therapy approaches (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy), noise therapy, physiotherapy, hearing aid fitting and, in individual cases, drug therapy (for insomnia, depression, anxiety) or neuromodulation may be considered. (Fig. 5). Due to the heterogeneity and challenging assessment of the tinnitus origin, the patient-specific comorbidities, and the lack of evidence of many therapeutic modalities due to poor methodological quality of studies, it is challenging for the treating physician to choose the right therapeutic modality.

Tinnitus Counseling

In order to counteract a chronification of tinnitus or to offer support to patients with already chronic tinnitus, it is essential to educate the patient about the clinical picture and its coping strategies. In many cases, tinnitus cannot be cured, but acceptance of the sound and habituation to it can be achieved. Counseling includes not only education on the proper use of noise in everyday life, but also the elimination of fears. Encouraging the patient to try to perceive the tinnitus by defocusing and to get used to the sound can help to avoid secondary symptoms such as psychological stress, sleep problems, difficulty concentrating, and restrictions in the social environment.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

In cognitive behavioral therapy, the patient is encouraged and motivated to address his or her thoughts, fears, attitudes, and evaluations in relation to the symptom. This therapy modality emerged in the 1960s and is based on the assumption that the way we think determines our psychological and physical well-being. Cognitive behavioral therapy is about taking an active role in shaping the process of perception and thus managing effects of a disease. This strategy is the best-studied psychotherapeutic approach to achieving illness understanding and coping in tinnitus patients and is thus considered the gold standard [7].

Noise therapy (Sound therapy)

Various therapeutic approaches using sounds can be used with tinnitus patients. The common principle is from the use of external sound stimuli with the goal of reducing the patient’s attention to the tinnitus or changing the patient’s response to the tinnitus. Like most other therapeutic approaches, this does not cure tinnitus, but improves coping. For example, the use of background noises such as the sound of the sea, birdsong, rustling leaves, etc. can be used with the aim of drowning out the tinnitus and thus, for example, reducing the tinnitus level. to make it easier to fall asleep. Other variants include wearing a small noise generator behind the ear (“noiser”, similar to a hearing aid), which plays variable sounds and thus drowns out the tinnitus completely or partially even in everyday life, depending on the setting [9].

Hearing aids

Conventional hearing aids can be used in tinnitus patients with an appropriate hearing loss to compensate for the lack of auditory input. This therapy proves to be very effective especially in patients with a higher degree of hearing loss, e.g. due to presbycusis. These are limited in their usefulness in the high frequencies and in the case of complete loss of function of the inner hair cells. In cases of profound or complete hearing loss, the use of cochlear implants can result in significant and sometimes complete suppression of tinnitus [8,13,14].

Drug therapy

There is no solid data to date demonstrating a long-term benefit of specific drug therapy for the treatment of tinnitus compared to placebo. Various medications such as intravenously administered local anesthetics (lidocaine) or antidepressants have been tested in studies, but no long-term effects have been demonstrated and, in view of the side effect profile, the use of this medication for the sole treatment of tinnitus is not justified. Treatment of comorbidities such as sleep disturbance, muscle tension, or psychiatric problems may also lead to relief of tinnitus.

Neuromodulation

The pathophysiology of ringing in the ears, with evidence of altered neuronal activity in the CNS, has led to the evaluation of neuromodulatory approaches to the treatment of tinnitus in experimental studies. However, neuromodulation in the form of transcranial current or magnetic stimulation, neurofeedback, or acoustic stimulation methods aligned with tinnitus frequency are still the subject of research and without clearly proven evidence. Further research is needed here [12].

Take-Home Messages

- Unfortunately, a cure for most forms of tinnitus does not currently exist. However, management and guidance of the patient to cope with tinnitus are possible and useful.

- Every tinnitus should be clarified by a detailed and empathetic anamnesis interview with assessment of the tinnitus severity (classification, stress situation) as well as an otoscopic and audiological examination.

- Referral to an ORL physician should generally be made by those who experience high levels of stress, perceive a clearly unilateral ringing in the ear (especially if this is synchronous with the pulse), suffer from hearing loss, and/or perceive other ear symptoms (otalgia, otorrhea, dizziness).

- Causal treatment of specific pathologies and especially psychiatric comorbidities should be prioritized.

- Symptomatic tinnitus treatment primarily includes tinnitus counseling, and in some cases, cognitive behavioral therapy, acoustic stimulation (and neuromodulation).

- The indication for pharmacological therapy is currently limited to certain tinnitus subtypes and the treatment of comorbidities such as sleep or anxiety disorders and depression.

- In difficult cases or in decompensated tinnitus, we recommend an interprofessional therapeutic approach.

Literature:

- Langguth B, et al: Tinnitus: causes and clinical management. Lancet Neurol 2013.

- AWMF Guideline “Chronic Tinnitus

- Biswas, Hall: Prevalence, Indidence, and Risk Factors for Tinnitus. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences (book series) 2020.

- Moller A, Langguth B, DeRidder D, Kleinjung T: Textbook of Tinnitus.

- Weisz, et al: High-frequency tinnitus without hearing loss does not mean absence of deafferentation. Hear Res 2006.

- Job, et al: Susceptibilits to tinnitus revealed at 2kHz range by bilateral lower DPOAEs in normal hearing subjects with noise exposure. Audiol Neurootol 2007.

- Jastreboff, et al: Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosc Res 1990.

- Baguley, et al: Cochlear implants and tinnitus. Prog Brain Res 2007.

- Hoare, et al: Sound Therapy for Tinnitus Management: Practicable Options. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2014; 62-75.

- www.tinnitracks.com/de/tinnitus/behandlung

- www.ata.org/managing-your-tinnitus

- Hébert, et al: Tinnitus Severity is Reduced with Reduction of Depressive Mood – a Prospective Population Study in Sweden. PLoS One 2012.

- Okamoto H, et al: Counteracting tinnitus by acoustic coordinated reset neuromodulation. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2010.

- Wielopolski, et al: Alexithymia Is Associated with Tinnitus Severity. Front Psychiatry 2017.

- Peter N, Kleinjung T: Neuromodulation for tinnitus treatment: an overview of invasive and non-invasive techniques. JZ Univ Sci 2019.

- Peter, et al: The Influence of Cochlear Implantation on Tinnitus in Patients with Single-Sided Deafness: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019.

- Peter, et al: Cochlear implants in single-sided deafness – clinical results of a Swiss multicentre study. Swiss Med Weekly 2019.

- Wu C, et al: Tinnitus: Maladaptive auditory-somatosensory plasticity. Hear Research 2016.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(5): 10-14

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(3): 16-20.