After a confirmed diagnosis of arterial hypertension, one should assess the severity, overall cardiovascular risk, and any organ damage present. First-line antihypertensives are RAAS blockers alone or combined with Ca antagonists or diuretics. If hypertension persists despite triple therapy, an aldosterone antagonist may be used. Lifestyle changes are recommended regardless of the degree of hypertension.

According to the Swiss Heart Foundation, hypertension is the most common diagnosis made in a physician’s office in Switzerland [1]. Individuals with high blood pressure do not usually feel ill or experience discomfort. Compared to people with normal blood pressure, people with untreated high blood pressure are twice to ten times more likely to suffer a stroke or heart attack or develop heart failure, depending on the severity: it is therefore very important to measure blood pressure at every opportunity, provided that measurement at rest is possible.

Correct diagnosis allows early antihypertensive therapy, which can serve to reduce these complications, many sequelae, and deaths. Lifestyle changes and antihypertensive medications are available to treat hypertension. Experience has shown that most patients require the combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological strategies. This article summarizes the issues surrounding hypertension that are important for primary care physicians.

How is the diagnosis of arterial hypertension confirmed?

To detect hypertension, blood pressure must be measured several times at rest: A single measurement or measurements that are not taken at rest are not useful for diagnosis. In addition, there is much debate as to whether the blood pressure readings in the office are the correct ones to confirm a diagnosis. Complementary options include home measurement and 24-hour blood pressure measurement [2,3]. Although these methods can be very useful, the vast majority of studies are based on what is called “office blood pressure.”

If the blood pressure values are above 140/90 mmHg in a single measurement, at least three additional measurements within a few weeks should confirm the elevated blood pressure values to be certain that hypertension is present. The current guidelines [2,3] recommend motivating patients to measure their blood pressure values according to written instructions in this time frame. If possible, 24-hour blood pressure measurement should also be performed. This last examination helps us to identify special forms of hypertension (such as white coat hypertension or masked hypertension), moreover, nocturnal hypertension can be detected.

For many patients, however, it is not easy to make the diagnosis because their blood pressure values fluctuate greatly or are only too high in certain life situations. Many people measure blood pressure only when they feel certain symptoms (headache, anxiety, palpitations…) and thus measure the effect of this discomfort on blood pressure: we must not compare such values with the normal values at rest.

Clarifications in case of confirmed hypertension

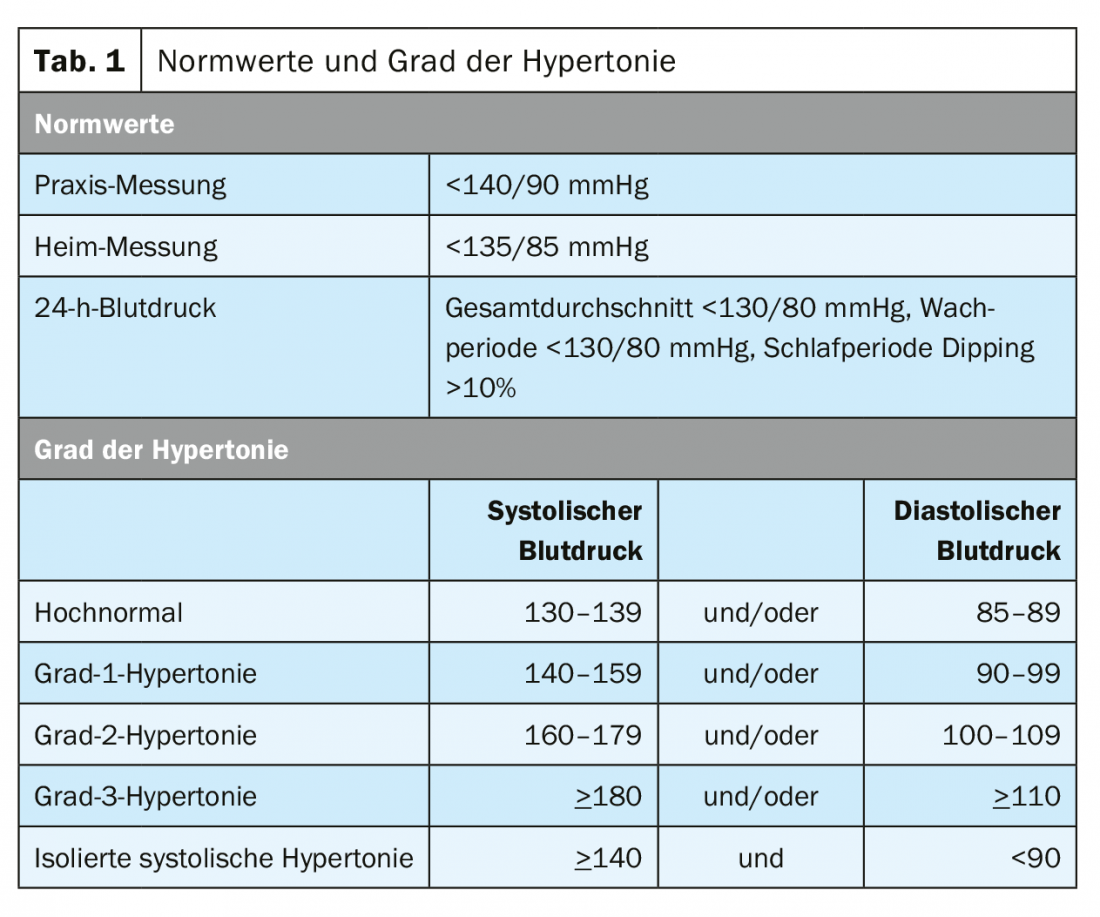

After confirming the diagnosis of arterial hypertension it is important to determine the degree of hypertension (Table 1), assess the overall cardiovascular risk, evaluate any organ damage that may be present, and rule out a cause of hypertension.

Search for a cause of hypertension

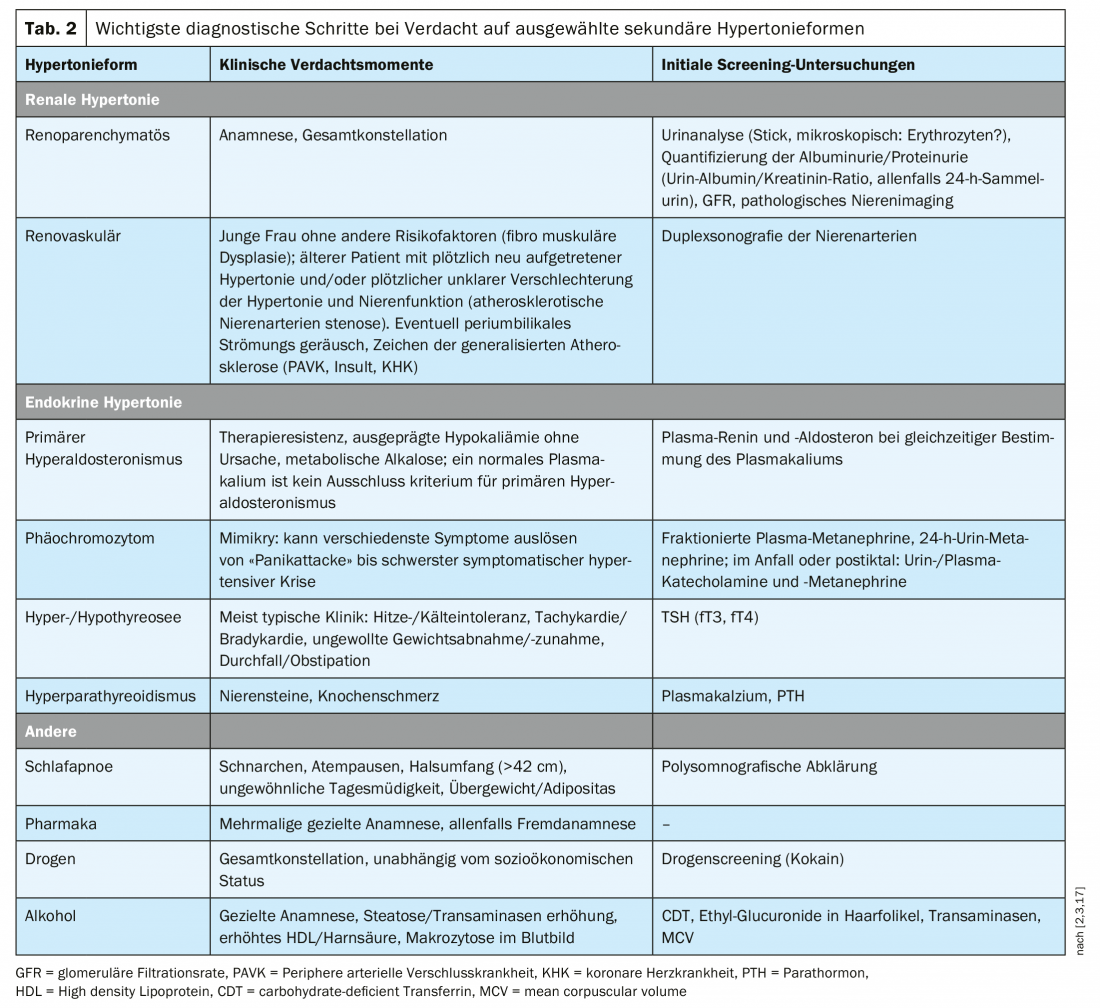

In patients with young age, very high blood pressure (grade 3), sudden rise or rapid deterioration of blood pressure, clinical evidence/suspicion of endocrine disease or renal disease or sleep apnea, and also in difficult-to-control/therapy-refractory hypertension (uncontrolled blood pressure despite lifestyle measures and antihypertensive therapy with diuretic plus at least two other antihypertensives), it is useful to look for a cause of arterial hypertension. Diagnosis is based on history and physical examination as well as laboratory tests. The detailed tests used to diagnose the various forms of secondary hypertension are summarized in Table 2.

Hypertension-related end-organ damage

A 12-lead ECG, laboratory (renal function and urinalysis with microscopic urine examination, microalbuminuria (albumin/creatinine ratio) and proteinuria) should be done in every patient with arterial hypertension. An extended search for hypertension-related end-organ damage should be performed based on history, clinical examination, and these routine technical examinations:

Specific [2,3]:

- Echocardiography is recommended in hypertensive patients with ECG abnormalities or symptoms/findings of heart failure and may be considered if left ventricular hypertrophy affects further management.

- Renal ultrasonography and renal artery Doppler should be considered in patients with impaired renal function, albuminuria/proteinuria, or suspected secondary hypertension.

- Cognitive function testing should be considered in any hypertensive patient over 75 years of age.

Evaluation of cardiovascular risk

To estimate total cardiovascular risk, the following additional cardiovascular risk factors should be evaluated in each patient with arterial hypertension: Family history of cardiovascular disease, age (men >55-years-old, women >65-years-old), tobacco/nicotine use, obesity, physical inactivity, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia.

Cardiovascular risk can be evaluated for the Swiss population by the AGLA score [4], which calculates the absolute risk of suffering a fatal coronary event or a nonfatal myocardial infarction within 10 years, or by the SCORE of the European Society of Cardiology [5], which calculates the absolute risk of a fatal myocardial infarction within the next 10 years. Patients with arterial hypertension automatically belong to the very high cardiovascular risk group if they have already experienced an atherothrombotic event, have type 2 or type 1 diabetes mellitus with end-organ damage such as microalbuminuria or GFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2 [5,6]. Patients with arterial hypertension automatically belong to the group with high cardiovascular risk, when a single risk factor is highly elevated (e.g., LDL-C >4.9 mmol/l or BP >180/110 mmHg), in uncomplicated type 2 diabetes mellitus or long-standing type 1 diabetes (More than 10 years), and when GFR is 30-59 ml/min/1.73m2 ). [5,6].

Therapy of arterial hypertension

The goal of treatment for hypertensive patients is long-term reduction of cardiovascular risk. For optimal risk reduction, it is necessary to identify and treat all additional risk factors that can be influenced. As a general rule, blood pressure should be <140/90 mmHg (practice measurement). In most patients, it should be lowered within the ideal range of 120-130/70-80 mmHg [2,3].

Lifestyle changes should be recommended in every patient with arterial hypertension, regardless of the degree of hypertension and cardiovascular risk. These factors influence the timing of initiation of pharmacologic therapy [2,3]. The following measures should accompany drug therapy or, in uncomplicated grade 1 hypertension, be used as first-line treatment: Abstinence from nicotine, diet without much salt, rich in fruits and vegetables, alcohol restriction, physical endurance training, e.g. walking, running, cycling, swimming, weight reduction and stress-reducing strategies.

Most lifestyle changes cause only a small reduction in blood pressure; nonetheless, they are an essential part of therapy for reducing overall cardiovascular risk, improving blood pressure, and as an adjuvant to drug therapy.

Recent evidence suggests that pharmacological treatment of hypertension may have a beneficial effect on atherosclerosis. In addition, many randomized trials show that treatment of hypertension with various medications reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [7]. However, not all antihypertensives are equally effective in reducing cardiovascular events, and few antihypertensives have been shown to reduce mortality [8].

Nonetheless, the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines [3] recommend five different classes of drugs as first-line treatment for hypertension: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), and diuretics (thiazides and thiazide-like diuretics such as chlortalidone and indapamide). ACE inhibitors or ARBs alone or in combination with a calcium antagonist or a diuretic (thiazide-like preferred over hydrochlorothiazide, loop diuretics only in impaired renal function). The use of beta-blockers is limited to specific indications [3].

Which patients with hypertension should receive pharmacologic therapy?

The benefits of antihypertensive therapy are well established in the majority of patients with arterial hypertension: However, the use of medication in certain subgroups is still controversial. This includes patients with 1st-degree hypertension who have no cardiovascular disease or very high cardiovascular risk, patients with white coat or masked hypertension and low cardiovascular risk, patients with an estimated 10-year cardiovascular risk <10%, and patients older than 75 years who are not ambulatory or living in nursing homes.

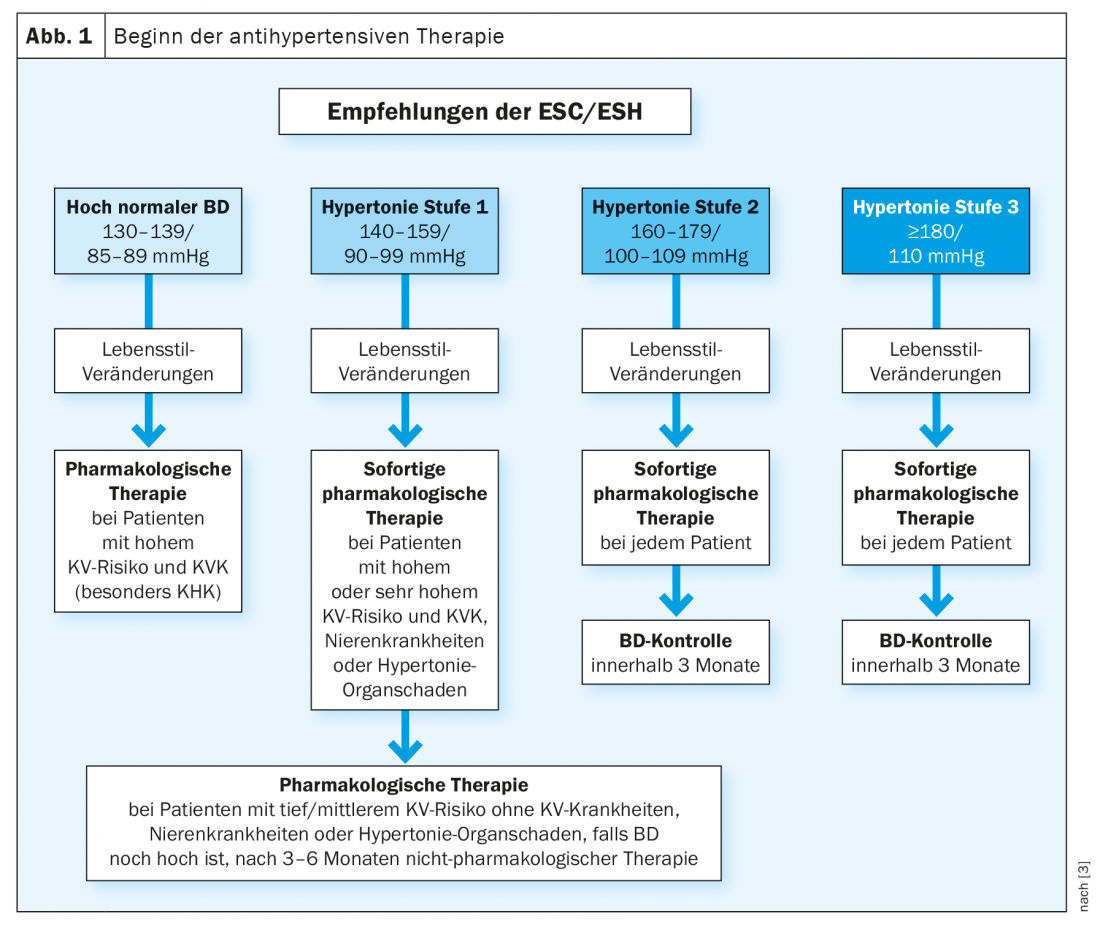

According to the ESC/ESH guidelines [3], in patients with grade 2 or 3 hypertension, antihypertensive pharmacologic therapy should be initiated promptly at the same time as lifestyle modifications. In individuals with high-normal blood pressure or grade 1 hypertension and very high cardiovascular risk, therapy should be initiated together with non-pharmacological therapy (Fig. 1) . The decision to initiate drug therapy should be made on an individual basis. Patients should be actively involved in such a decision.

Choosing the right therapy

Recommendations for the use of certain classes of antihypertensive medications are based on clinical trials that have tested the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of the medications and the effect in terms of reduced cardiovascular risk/events. Most patients with hypertension require more than one BP medication to reach their BP goal. As a result, it is suggested in the new guideline for the treatment of hypertension to use combination therapy at an early stage and, if possible, as a single-pill fixed-dose combination medication to improve patient adherence (exceptions are patients with grade 1 hypertension with SBD <150 mmHg, patients with high-normal blood pressure and very high risk of CT, or older-“frail” patients) [2,3]. The availability of multiple classes of antihypertensives allows physicians to individualize therapy according to clinical characteristics and patient preferences. In most patients, blood pressure remains outside the target range with monotherapy. In addition, combination therapy with drugs from different classes has a much stronger antihypertensive effect than doubling the dose of a single agent [9].

If combination therapy is needed, the guidelines recommend a long-acting ACE inhibitor or ARBs in combination (fixed, if feasible) with a long-acting dihydropyridine-CCB or diuretic as initial therapy. The combination of an ACE inhibitor or ARBs with a thiazide diuretic is considered more beneficial when a thiazide-like diuretic (chlortalidone or indapamide) is used instead of hydrochlorothiazide [3,10]. Even in the absence of head-to-head studies, available data suggest that thiazide-like diuretics such as chlortalidone and indapamide should be preferred over classic thiazide diuretics (eg, hydrochlorothiazide and bendrofluazide) [3,10,11]. ACE inhibitors and ARBs should not be used together [3]. The next step is the combination of RAAS blockers, Ca antagonists, and thiazide/thiazide-like diuretics [3].

The Danish Cancer Registry and the Danish Prescription Registry [12–14] have investigated the association between hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) use and the risk of basal cell, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. These two case-control studies showed that high cumulative HCTZ doses (>50 g) were associated with a dose-dependent increase in the risk of white skin cancer but not melanoma. The increase in risk was small for squamous cell carcinoma and negligible for basal cell carcinoma. Although the data are interesting, statistical associations from observational studies do not support a causal relationship. In addition, these studies have several limitations: Study of an exclusively fair-skinned population and lack of information on genetic predisposition, sun habits, and UV exposure. In addition, it should be noted that the risk reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality due to blood pressure reduction by HCTZ was much greater than the small risk increase for squamous cell carcinoma by HCTZ [15]. If blood pressure is not controlled with this triple therapy, a mineral corticoid receptor (MR) antagonist may be added [16].

In patients with difficult to treat/resistant hypertension, beta blockers, alpha blockers, or direct vasodilators could be added. In general, concomitant use of beta-blockers and non-dihydropyridine CCBs should be avoided because both classes of agents decrease heart rate [3].

Need for adherence to lifestyle changes and taking medications regularly.

Lifestyle changes and antihypertensive drugs lower blood pressure, but they do not cure arterial hypertension. If patients do not follow lifestyle changes consistently or do not take or discontinue medications regularly, blood pressure will rise again. However, organ damage from high blood pressure can only be prevented if blood pressure is lowered permanently and over the long term. That non-pharmacological/pharmacological antihypertensive therapy must be a lifelong companion is difficult for many patients to accept. Open doctor-patient discussions about the positive effects, mechanism of action and possible side effects of the drugs as well as regular monitoring are essential for future adherence.

Follow-up control in patients with hypertension

Patients should be directly involved in controlling their blood pressure from the beginning. Therefore, it is recommended that patients measure with a validated blood pressure monitor and according to written instructions and document the values in writing [2]. The frequency of these checks should be frequent at the beginning and after changes in therapy and can be reduced to once/week when antihypertensive therapy is stable. Patients should be advised against very frequent measurements that are not taken at rest.

Before and shortly after starting antihypertensive therapy, it is necessary for patients to be monitored by their physician. In these phases, the practice measurements and possibly the 24h blood pressure measurement are very important for the diagnosis and the adjustment of the therapy. When using certain medications, laboratory control may also be useful (creatinine for RAAS blockers, potassium for diuretics…). According to the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines [3], a check-up should be performed within the first 2 months after starting therapy to evaluate the effects on blood pressure and possible side effects. The frequency of further monitoring depends on the severity of the hypertension, the urgency of achieving blood pressure control, and any comorbidities present.

Once therapy is well established and the blood pressure goal is achieved, the guidelines recommend further monitoring at 3 and 6 months and then once a year thereafter. Exceptions are patients with low cardiovascular risk and no organ damage, in whom monitoring every 2 years is recommended [3]. Checking by non-physician health care professionals or taking home measurements and communicating electronically with the physician/physician are acceptable alternatives to reduce consequence checks.

Take-Home Messages

- The diagnosis of hypertension is confirmed by repeated practice blood pressure measurement. Supplementary options include home measurement and 24-hour blood pressure measurement.

- After confirming the diagnosis of arterial hypertension it is important to determine the degree of hypertension, assess the overall cardiovascular risk, evaluate any organ damage that may be present, and rule out a cause of hypertension.

- Lifestyle changes should be recommended, regardless of the degree of hypertension, cardiovascular risk, and need for pharmacologic therapy.

- RAAS blockers alone or in combination with Ca antagonists or diuretics are the antihypertensives of first choice. In persistent hypertension despite triple therapy (RAAS blockers, Ca antagonists, and diuretics), an aldosterone antagonist should be used.

- Measures that improve adherence (fixed-combination therapy, encouraging patient responsibility, and regular monitoring) are essential for successful treatment of hypertension.

Literature:

- www.swissheart.ch

- www.swisshypertension.ch

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al: 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018; 3×9(33): 3021-3104.

- www.agla.ch

- www.escardio.org

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al: 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2020; 41(1): 111-188.

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al: Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016; 387(10022): 957-967.

- van Vark LC, Bertrand M, Akkerhuis KM, et al: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors reduce mortality in hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors involving 158,998 patients. Eur Heart J 2012; 33(16): 2088-2097.

- Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK: Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med 2009; 122(3): 290-300.

- Burnier M, Bakris G, Williams B: Redefining diuretics use in hypertension: why select a thiazide-like diuretic? J Hypertens 2019; 37(8): 1574-1586.

- Roush GC, Ernst ME, Kostis JB: Head-to-head comparisons of hydrochlorothiazide with indapamide and chlorothalidone: antihypertensive and metabolic effects. Hypertension 2015; 65(5): 1041-1046.

- Pedersen SA, Gaist D, Schmidt SAJ: Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer: A nationwide case-control study from Denmark. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78(4): 673-681 e9.

- Pedersen SA, Johannesdottir Schmidt SA, Holmich LR: Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk for Merkel cell carcinoma and malignant adnexal skin tumors: A nationwide case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80(2): 460-465 e9.

- Pedersen SA, Schmidt SAJ, Klausen S: Melanoma of the Skin in the Danish Cancer Registry and the Danish Melanoma Database: A Validation Study. Epidemiology 2018; 29(3): 442-447.

- Sudano I, Mainetti C: Statement of the Swiss Society of Hypertension and the Swiss Society of Dermatology and Venereology. Hydrochlorothiazide and skin cancer: warning to be cautious. Swiss Medical Journal 2019; 100(16): 576.

- Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S, et al: Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet 2015; 386(10008): 2059–2068.

- Sudano I, Suter P: Hypertension: when and how to clarify a secondary etiology? Switzerland Med Forum 2014; 14(08): 146-150.

CARDIOVASC 2021; 20(3): 13-18