The cough is a symptom that can represent the entire spectrum from harmless to death-associated. It can be seen in workers, for example in mining, as a sign of interstitial lung disease, it is associated with smoker-associated diseases such as COPD, in children asthma or CF should be considered as a cause, and as of late 2019, the link to COVID-19 disease is on everyone’s mind.

The function of coughing is very simple to begin with: we cough to clear the lungs of particles and noxious substances. It becomes especially important when highly effective mucociliary clearance fails. And this can happen relatively quickly, especially with

- acute respiratory tract infection

- Inhibition of cilia by substances in cigarette smoke

- Epithelial metaplasia in COPD

- Bolus Aspiration

In healthy individuals without a cough, the ciliated epithelium is capable of removing approximately 60% of inhaled particles from the lungs within one hour. However, if the patient is a smoker or, for example, has an acute respiratory tract infection, mucociliary clearance is reduced to only 10%, explained Dr. Tsogyal Daniela Latshang, Chief of Pneumology/Sleep Medicine at the Graubünden Cantonal Hospital [1]. Several cough bursts have a significantly higher cleansing effect, but at about 15% it is still insufficient. Therefore, when smoking a cigarette, the soot from the cigarette will remain in the lungs.

Cough triggers

There are several cough receptors that are a.o. localized in the auditory canal (vagal innervation), upper airways, larynx, bronchial system, peripheral airways (cough in diseases of the lung such as alveolitis, pulmonary fibrosis), pleura and diaphragm. Thereby it is v.a. the nervus vagus, which does the main work here.

The cough receptors consist of rapidly adapting receptors that are stimulated by smoke, air pollution, hyper- or hypotonic NaCl stimulation, mechanical stimuli, bronchial obstruction, or pulmonary hyperhydration (in heart failure). In addition, there are slow-adapting receptors and C-fiber or chemoreceptors that respond to bradykinin (ACE inhibitors), capsaicin, and acid (in reflux). Major trigger factors for a cough include medications, most notably ACE inhibitors, tobacco smoking, upper respiratory tract affection, GERD, bronchial asthma, eosinophilic bronchitis, and lung diseases such as interstitial pneumopathies, bronchiectasis, lung carcinoma, or infiltrates.

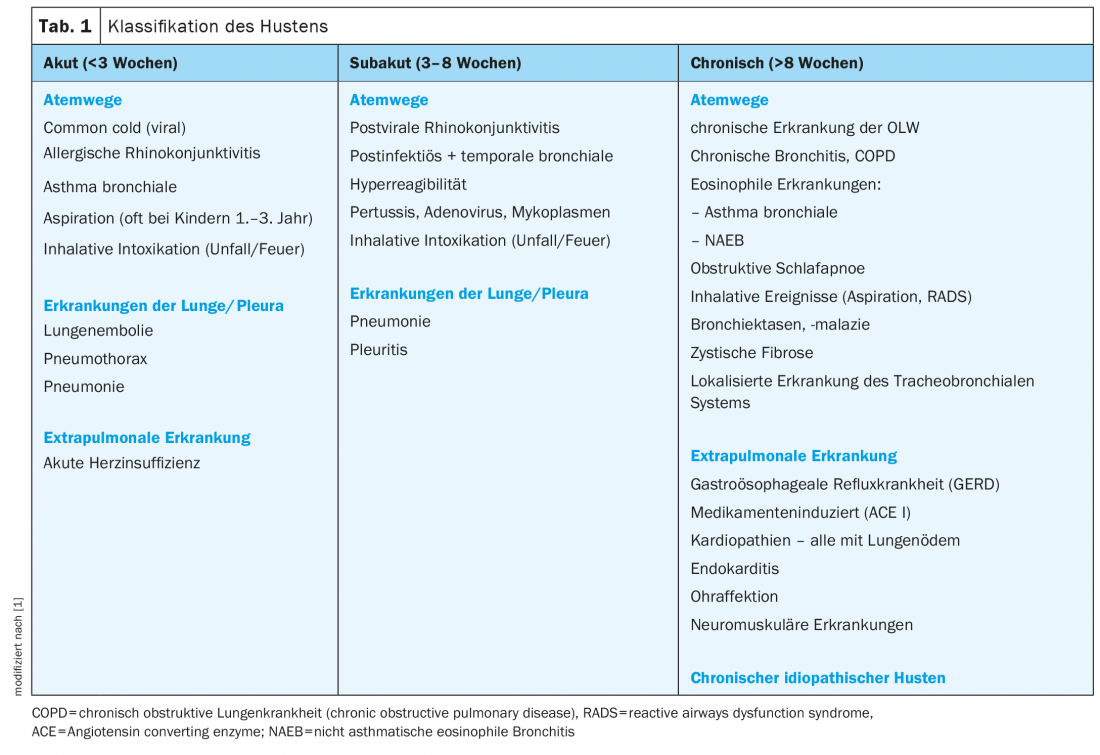

Cough is classified according to the duration of the symptom (tab. 1) . For a duration of up to 8 weeks, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, or pleurisy should be considered with regard to the lungs and pleura. In the case of chronic cough longer than 8 weeks, it is essential to find the cause. Extrapulmonary diseases such as GERD, endocarditis, cardiopathies, and neuromuscular diseases must be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

If no other etiology can be found, chronic idiopathic cough is assumed to be the diagnosis of exclusion. It is considered a disease in the sense of a neuropathy and appropriate therapy is initiated. Chronic refractory cough should be interpreted as having a hypersensitive cough reflex, trigger factors have been found, these have been treated optimally and for a sufficiently long time, but the cough continues to persist, so that a neuropathic component is also assumed here and appropriate therapy is initiated.

Trigger factors

Besides drug-associated cough, smoking remains the most common trigger of chronic cough. It provokes the cough and can lead to non-obstructive chronic bronchitis and COPD, it increases the risk of manifestation of asthma and in asthma bronchial hyperreactivity. In addition, smoking leads to steroid resistance in asthma patients. Inhaled therapies for chronic bronchitis or COPD are certainly important for symptom control and exacerbation prevention, Dr. Latshang said, but do not change the patient’s prognosis. For them in this context, therefore, of greater importance: smoking cessation, vaccinations and physical activation. Oxygen therapy also appears necessary. In special cases, such as heterogeneous or advanced emphysema and former smokers, lung volume reduction (surgical, endoscopic, or lung transplantation) may also be recommended. According to the expert, under certain conditions, therapy with Roflumilast can also be or Azithromycin can be elicited.

Upper Airway Cough Syndrome (UACS) involves a sensitive cough reflex with chronic rhinosinusitis +/- PND +/- polyposis, which may be allergic, infectious, or vasomotor. Chronic pharyngitis, laryngitis, or sinu-bronchial syndrome may also be associated with UACS. Diagnostically, a “mucus street” can be detected in the throat and the feeling of the secretion is usually very sensitive. Dr. Latshang recommends a trial of therapy with nasal corticosteroids for min. 6 weeks, with short-term decongestant nasal treatment if needed. Daily nasal rinses or H1 antihistamines with pseudoephidrine may also be useful. An ENT evaluation and surgical remediation may be indicated.

Another cause of chronic cough is gastroesophageal reflux. Here, too, there is a hypersensitivity of the cough reflex. In reflux-related cough, on the one hand, gastroesophageal reflux in the distal esophagus may lead to cough via irritation of cough receptors. In addition, there is also the aspiration theory: via microaspirations, which are eructated, lead to irritation of the upper and lower respiratory tract and thus to coughing. Symptoms may be variable to absent. Therapeutic recommendations include dietary changes, weight reduction, elevation of the upper body (10 cm), and medication PPI high doses for at least 3 months, if necessary combined with metoclopramide 3× 10 mg/d. In contrast, a routine examination by means of instruments is not indicated.

In bronchial asthma, the cough often occurs as an asthma equivalent. Here, no obstruction is found in the lung function. Patients often report dry cough and early morning awakening with cough. There is no dyspnea, but bronchial hyperresponsiveness can be demonstrated. The diagnosis for this can only be made after successful completion of therapy with inhaled steroids (ICS, high doses, administered for a longer period). Due to lack of evidence, therapy with LABA is not recommended.

Finally, eosinophilic bronchitis accounts for about 15% of all chronic coughs. In these cases, sputum eosinophilia greater than 3% and elevated FeNO are found, but there is no bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Coexistence with COPD, bronchiectasis, and occupational lung disease is common. Therapeutically, ICS, possibly as long-term therapy, usually show a good response (e.g., budesonide 400 μg/d for 4 weeks).

If none of the above causes can be considered, an idiopathic chronic cough can be established as a diagnosis of exclusion. This affects women more often than men, often during the period of menopause. Associations with autoimmune disease and hypothyroidism are not uncommon, and basement membrane thickening without inflammation or mucus can often be demonstrated. The FeNO is normative. A hypersensitive cough reflex is quite typical in the history. Rapid FEV1 loss (63 ml/yr) is detectable in patients. Since it is a neuropathy, it can be treated with gabapentin, pregabalin, or amitryptiline, respectively. Opiates and cannabinoid agonists may also be used. Nonpharmacologically, Dr. Latshang also advised physical therapy, voluntary cough suppression, breathing techniques, and vocal hygiene.

Source:

- Workshop “Cough: What the practitioner needs to know”; 60th Davos Medical Congress – Online Event, 12. February 2021.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(2): 32-33 (published 8.5.21, ahead of print).