One of the most common reasons for consultation in primary care practices and emergency departments is lumbar back pain. A 2012 systematic review estimated a global point prevalence of activity-limiting back pain >1 day of 12% and a 1-month prevalence of 23%. Low back pain can be classified by duration and cause. Causally, nonspecific lumbar low back pain (synonym lumbago, lumbalgia, popularly known as “lumbago”) can be distinguished from specific lumbar low back pain.

One of the most common reasons for consultation in primary care practices and emergency departments is lumbar back pain. A 2012 systematic review estimated the global point prevalence of activity-limiting back pain >1 day to be 12% and the 1-month prevalence to be 23% [1].

Low back pain can be classified by duration and cause. Causally, nonspecific lumbar low back pain (synonym lumbago, lumbalgia, popularly known as “lumbago”) can be distinguished from specific lumbar low back pain. Specific low back pain that can be attributed a mechanical cause (disc hernia, spinal stenosis) or somatic cause (tumors such as skeletal metastases, infections such as spondylodiscitis or epidural abscess, underlying rheumatologic conditions such as seronegative spondyloarthropathies) accounts for only a small proportion. They require extended diagnostics and therapy. Nonspecific back pain comprises the largest proportion at 85%. The majority of patients presenting with nonspecific low back pain have a benign course and the back pain resolves during the acute phase (12 weeks) lumbar low back pain. Despite the generally low cost of treatment, back pain has a major impact on the national economy due to its high lifetime prevalence. The high costs result, on the one hand, from the long-term treatment of complex courses and, on the other hand, from indirect costs due to absences and reduced performance at work. It is therefore all the more important to evaluate the risk of chronification at an early stage and to provide patients with appropriate therapeutic measures at an early stage that will enable them to minimize their work absences.

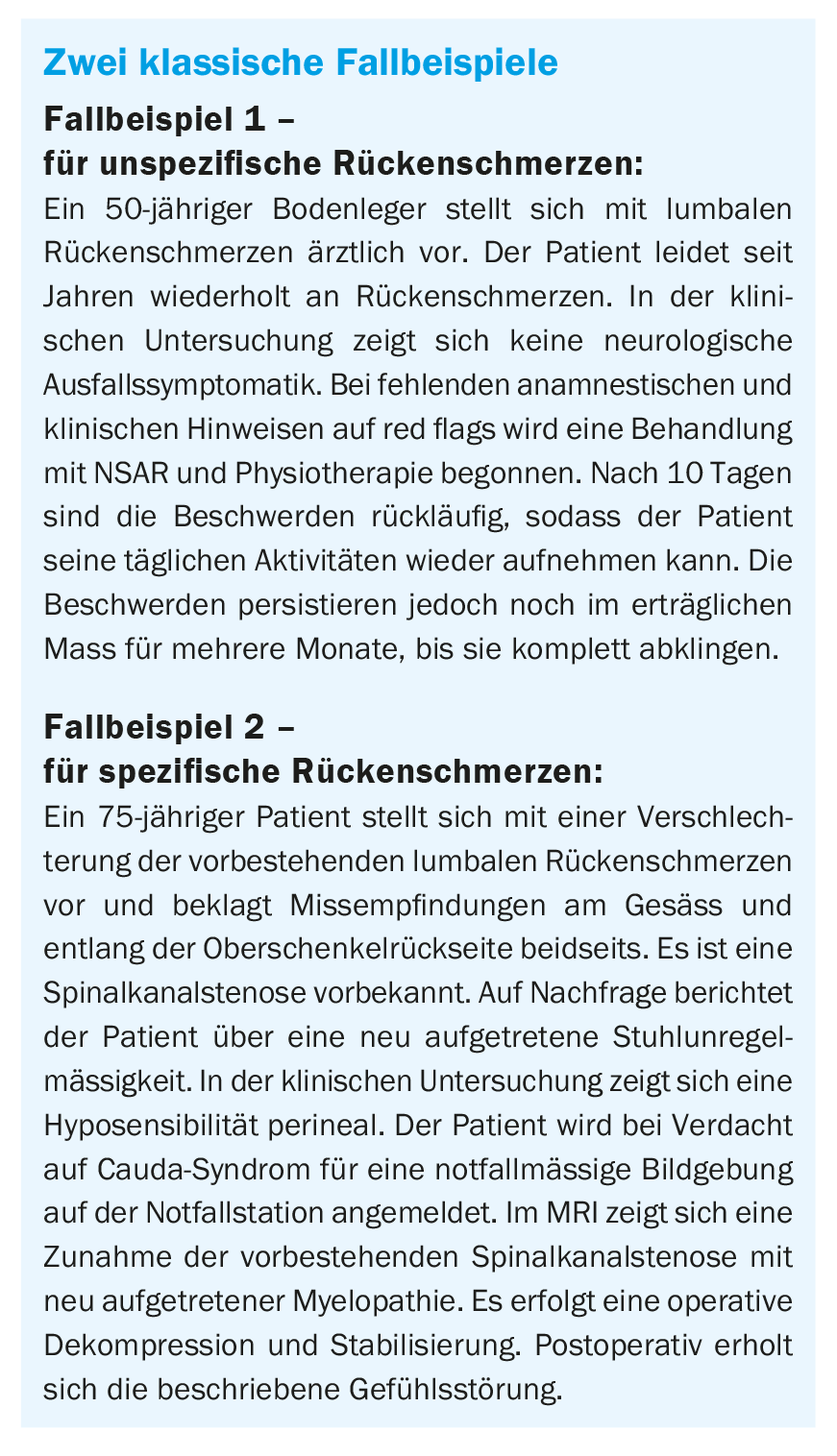

Chronification process

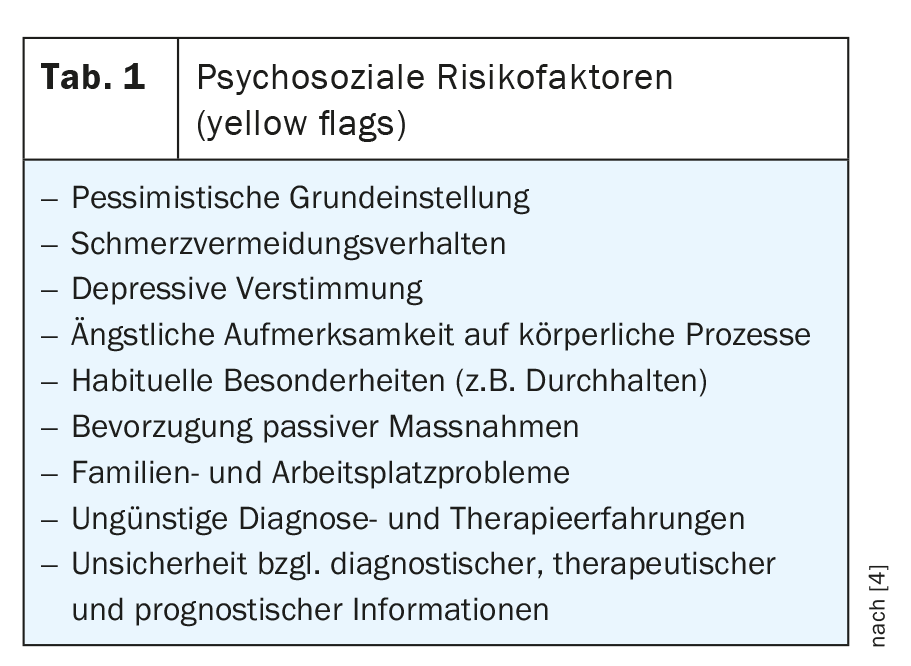

In the transition from acute to chronic pain, the patient’s impairment becomes multifaceted [3]. Various factors reinforce each other. As a result of the functional impairment, the patient’s mobility is significantly reduced, he can only partially fulfill his private and professional roles, and pain-related behavior takes up more space. Cognitively-emotionally, this manifests itself in reduced mood and state of mind as well as unfavorable thinking patterns such as catastrophizing or the belief of severe impairment. These factors are particularly evident in the process of pain chronification in pre-stressed patients who were already psychologically, socially and occupationally stressed before the pain episode. As a result, unfavorable patterns of thinking and behavior as well as psychosocial risk constellations of patients should be identified early on, knowing that their risk for chronicity is increased. Corresponding to the risk factors for a specific cause (red flags), the “yellow flags” were formulated as risk factors for chronification (Tab. 1 “yellow flags”).

Diagnostics

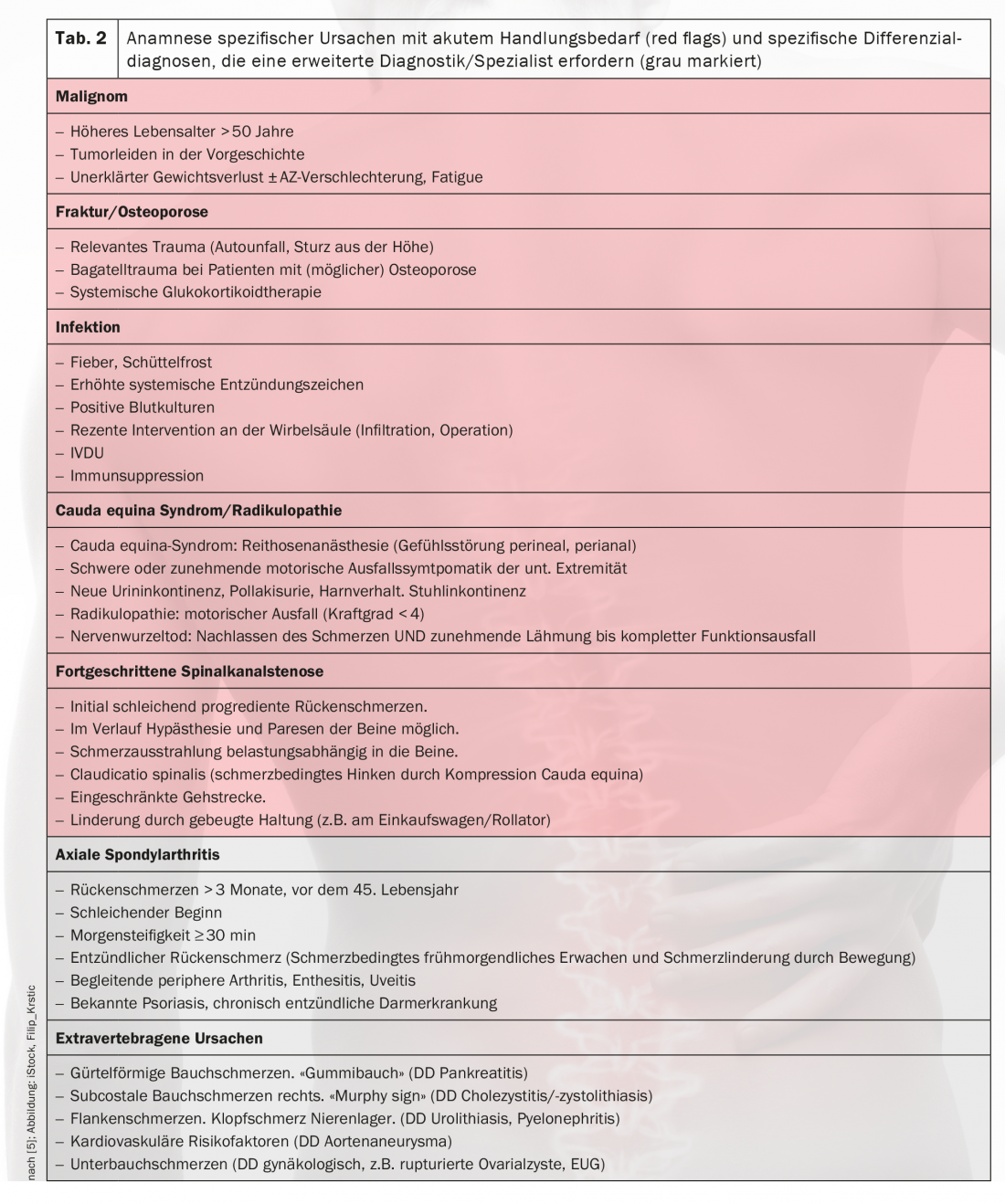

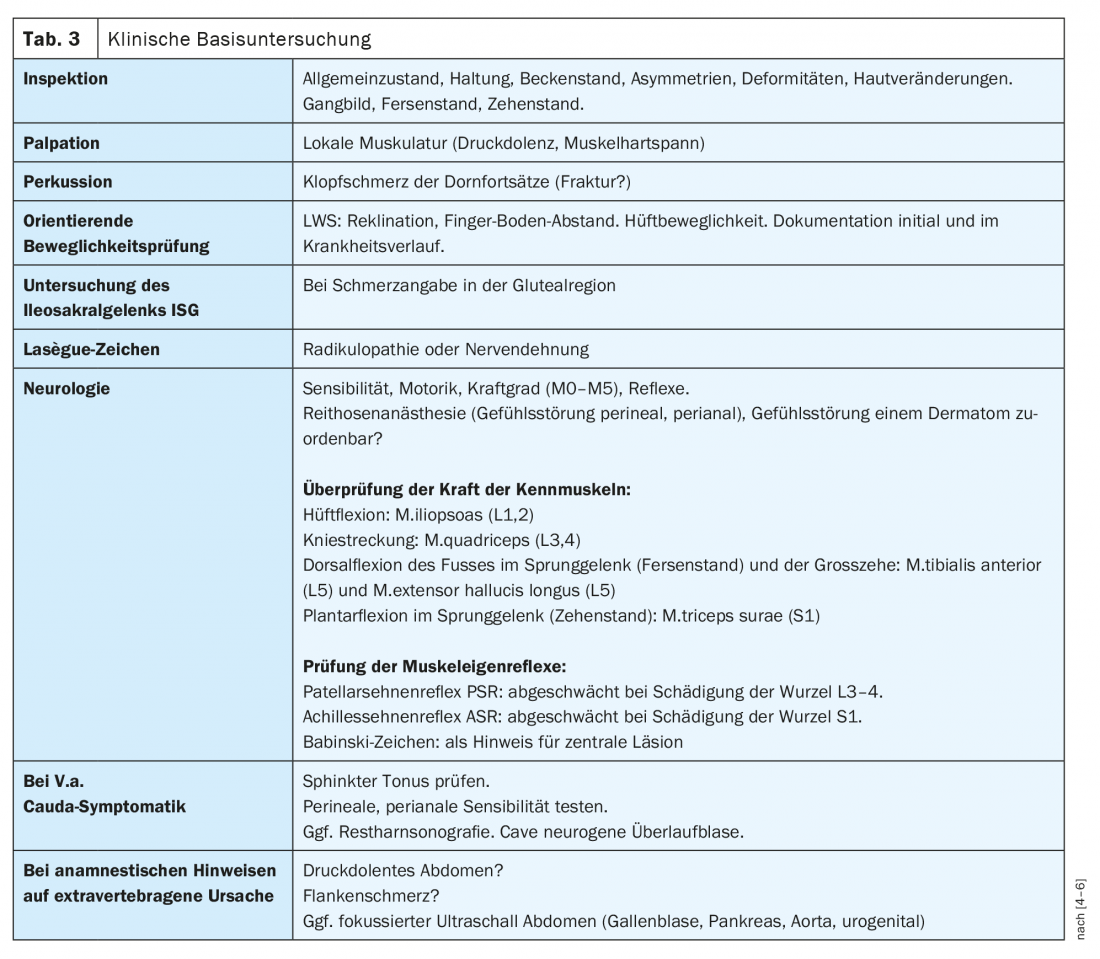

During the work-up in the primary care practice of patients presenting for the first time with lumbar back pain, the history is central. It includes the pain characteristics and the questioning of warning signals for a specific cause (Tab. 2 “red flags”) . With regard to pain characteristics, localization, intensity (VAS 1-10/10), quality (nociceptive, neuropathic), temporal course (variability of pain during the course of the day) and behavioral dependence (rest pain, exertion pain; pain-associated sleep disturbances) are queried. In addition, it is ascertained how daily activities are restricted as a result of the pain, what the current private/occupational burden looks like, and whether there have been previous episodes of pain. Furthermore, the medical history should take into account the recording of psychosocial risk factors at an early stage. The basic physical orthopedic examination is extended accordingly if there is evidence of a specific cause of the back pain (Table 3).

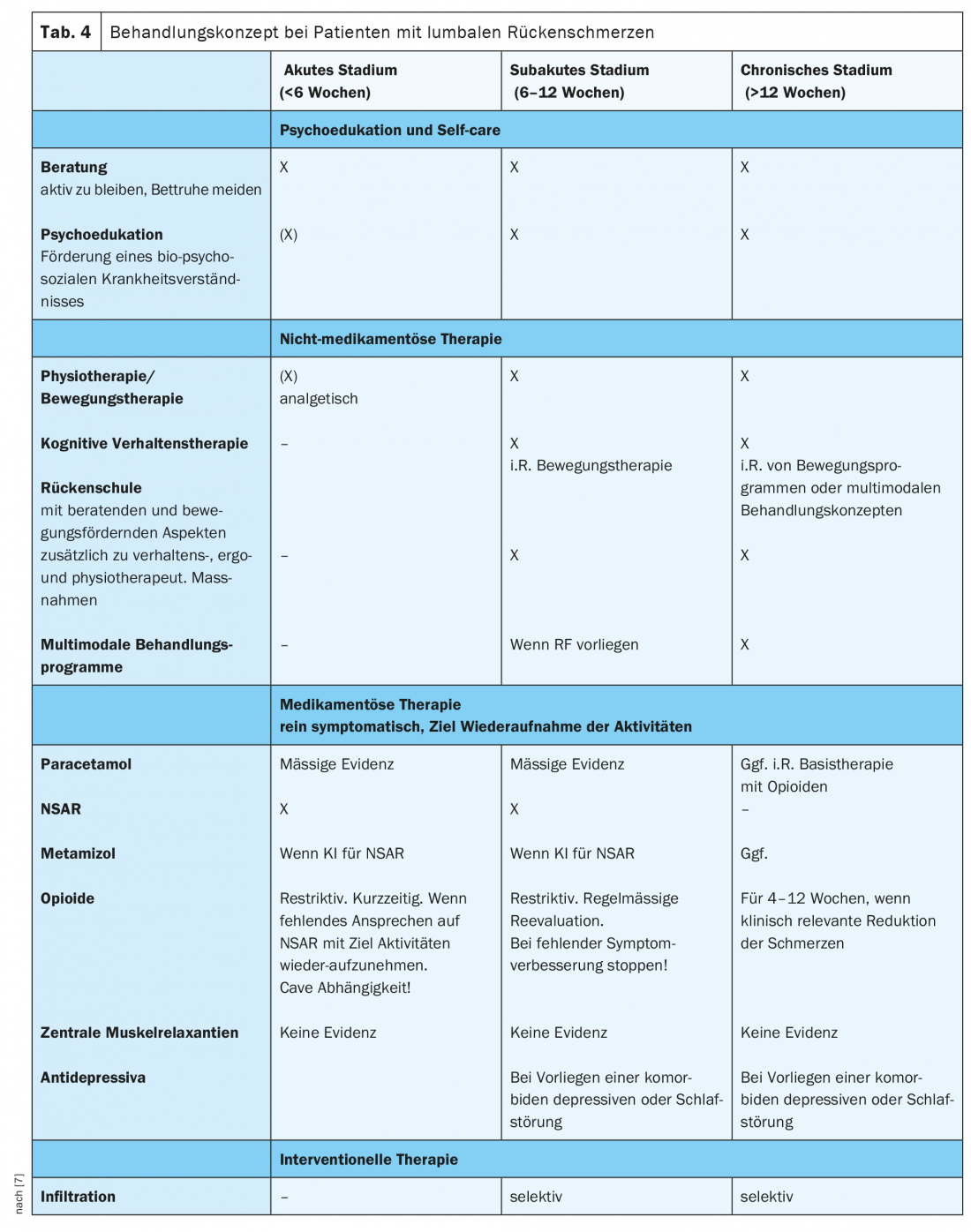

Using these diagnostics, the first treating physician can differentiate the cause of the back pain into specific and non-specific during the initial consultation and initiate measures for symptom control. Drug therapy is listed in Table 4 .

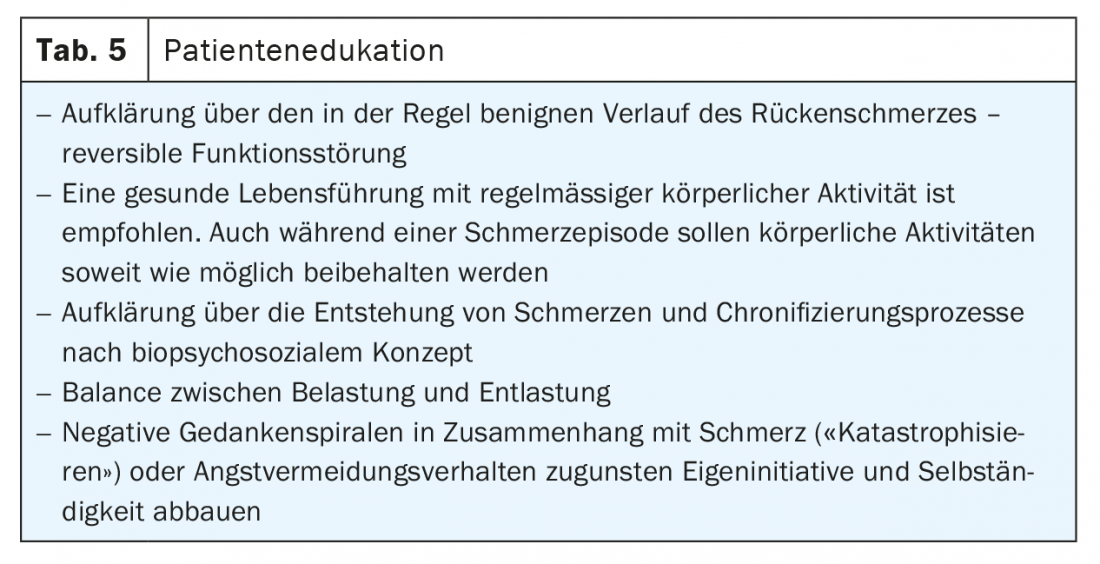

In patients with nonspecific low back pain without the presence of “red flags,” imaging is not necessary for the first 4-6 weeks. The focus is on informing the patient about the benign nature of the symptoms and motivating him or her to remain active and to avoid protective behavior (Table 5) .

Clarify at initial consultation:

- Is there evidence of a specific cause requiring acute action (cauda syndrome, fracture, tumor, infection)?

- Is there any neurological failure symptomatology?

- Are there risk factors for chronicity?

Extended diagnostics and therapy in case of indications for a specific cause of the pain

Routine determination of laboratory parameters is not recommended. In the presence of “red flags” with suspicion of infection, tumor, or inflammatory process, a baseline laboratory is necessary. Urgent action is required by the practitioner when, based on the clinic, there is a suspicion of unstable fracture (fracture with spinal compression), spinal infection, cauda syndrome, mass prolapse, or tumor with higher grade nerve compression. In this case, emergency admission to an appropriate hospital for further evaluation and therapy is indicated. Even if the cause of the pain is suspected to be extravertebral, a referral of the patient is usually necessary. In the case of radiculopathy, the urgency of clarification results from the symptoms of failure [8]. Prompt MRI is indicated for progressive motor deficits (emergency for more severe deficits) and evaluation by the specialist is indicated. In the case of only mild motor deficit symptoms without accompanying warning signs, a therapy attempt should primarily be made over 2- 4 weeks and the MRI should be planned as an outpatient only in the absence of improvement. Here, it is critical that the patient be instructed to re-present to a physician in the event of increasing motor deficit symptoms, disabling pain, or cauda symptomatology in the interim.

Essential in the case of nerve compression on MRI is whether it correlates with the clinic and causes the pain. If radicular symptoms persist, a specialist evaluation is recommended, ideally with MRI findings, with a question about interventional pain therapy (infiltration) or surgery.

Diagnostics and therapy for persisting complaints

After 2-4 weeks of guideline-compliant therapy, a re-evaluation of the complaints should take place. In case of clinical improvement with resumption of daily activities, measures can be de-escalated.

In the majority of patients with nonspecific low back pain, the symptoms resolve relevantly after an interval of 4-6 weeks. If the symptoms persist over this time to a degree that is limiting for the patient, clinical evaluation should be repeated and imaging should also be considered. It is important to keep in mind that in everyday clinical practice, many imaging procedures occur without clinical warning signs being present. The U.S. Choosing wisely initiative (www.choosingwisely.org) promotes physicians’ communication with patients about evidence-based diagnosis and treatment. Along these same lines, the American Academy for Family Medicine and the National Low Back Pain Care Guideline in Germany have recommended that imaging should not be performed for low back pain without evidence of a specific cause for the first 4-6 weeks. Otherwise, there is a risk that degenerative changes in the spine will be attributed to the presenting complaints, because numerous asymptomatic patients also show degenerative changes in the spine [9]. In addition, it must be taken into account that a finding on imaging may result in extended diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, which in principle promote chronification [10]. These imaging procedures without a clear indication must be avoided, even if the patient urges diagnostic testing. If the symptomatology and clinical course are “adequately explained,” imaging should not be pushed because there is no evidence for it in chronic nonspecific low back pain [11]. A repetition of the imaging during the course is not recommended if the symptoms remain largely unchanged!

In patients with persistent nonspecific low back pain, once a specific cause has been ruled out again, psychosocial and workplace risk factors (Table 1) should be evaluated at this time at the latest. In patients without “yellow flags”, the main focus is on intensifying therapy measures (outpatient exercise programs by physiotherapists). In patients with emotional and behavioral risk factors, exercise therapy according to behavioral therapy principles has proven effective, since here often a reduction in the fear-avoidance attitude already leads to a relevant decrease in pain. Passive forms of therapy (e.g., massage, i.m. application of NSAIDs), which increase dependence on the practitioner and reduce independence and personal responsibility, are not recommended. Individual risk factors such as negative thinking and behavior patterns (e.g., “catastrophizing,” fear-avoidance attitude) can be specifically addressed with motivational interviewing.

In cases of prolonged incapacity (> 4 – 6 weeks) and the presence of “yellow flags”, the patient may be referred for an interdisciplinary assessment, which will evaluate the indication for an outpatient or inpatient multimodal therapy program. From this framework, it is also easier to involve the specialist for psychosomatics in the case of suspected somatoform pain disorder and to start an accompanying outpatient psychotherapy (usually cognitive behavioral therapy).

Take-Home Messages

- Only a small proportion of patients with lumbar back pain require acute action. There is little likelihood of missing this if a structured history and baseline clinical examination are performed.

- If the patient with acute lumbar back pain does not have any indications of dangerous courses (red flags) in the history and clinical examination, no diagnostic imaging needs to be performed initially (4-6 weeks).

- The presence of psychosocial and workplace risk factors increases the risk for chronicity of back pain.

- A nonspecific finding on imaging may result in extended diagnosis and therapy that promote chronicity.

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to Dr. Beat Lehmann and Dr. Susanne Eichenberger at the University Emergency Center, Inselspital Bern, for their critical review of the manuscript.

Literature:

- Hoy D et al: A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012 Jun; 64(6): 2028-2037.

- da C. Menezes Costa, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, et al: The prognosis of acute and persistent low-back pain: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012; 184(11): E613-E624.

- Maier C, Diener HC: Pain medicine. Interdisciplinary diagnosis and treatment strategies. 5th ed. 2016. Urban & Fischer Publishers.

- Eckardt A: Practice lumbar spine disorders. Diagnosis and therapy. Springer Verlag 2011.

- National health care guideline on low back pain. German Medical Association, Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF). 2nd ed. 2017.

- Reinhold M, Eicker SO, Schleicher P, Schmidt OI.: Wirbelsäule kompakt. Pocket guide of the German spine society. Schattauer Verlag 2018.

- Foster NE, et al: Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 2018 Jun 9; 391(10137): 2368-2383.

- Glocker F, et al: Lumbar radiculopathy, S2k guideline, 2018; in: German Society of Neurology (ed.), Guidelines for diagnosis and therapy in neurology. Online: www.dgn.org/leitlinien

- Jensen MC, et al: Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 69-73.

- Chou D, et al: Degenerative magnetic resonance imaging changes in patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Spine 2011; 36(21 Suppl): S43-S53.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Owens DK, et al: Diagnostic imaging for low back pain: advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154(3): 181-189.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(3): 6-11