Acute heart failure is a life-threatening situation that requires rapid and planned action. How does the clarification take place? What therapeutic measures are available? A look at initial stabilization in the hospital.

Acute heart failure (AHI) is defined as rapid onset or worsening of symptoms (often dyspnea and orthopnea) and/or clinical signs of heart failure (esp. congestion). It is a life-threatening medical situation that requires urgent evaluation and treatment and often hospitalization [1].

Approximately 80% of patients with AHI have preexisting chronic heart failure. More than 50% have heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF) [2]. In more than half of the patients, a trigger can be identified. Coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation are the most common underlying cardiac conditions, and diabetes is a very common comorbidity. Most patients are hypertensive or normotensive on admission. Only about 5-7% of all AHI are hypotensive (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), which is associated with an unfavorable prognosis. This is especially true in the presence of concomitant hypoperfusion (cool periphery) [3].

Diagnostics and initial prognostic evaluation

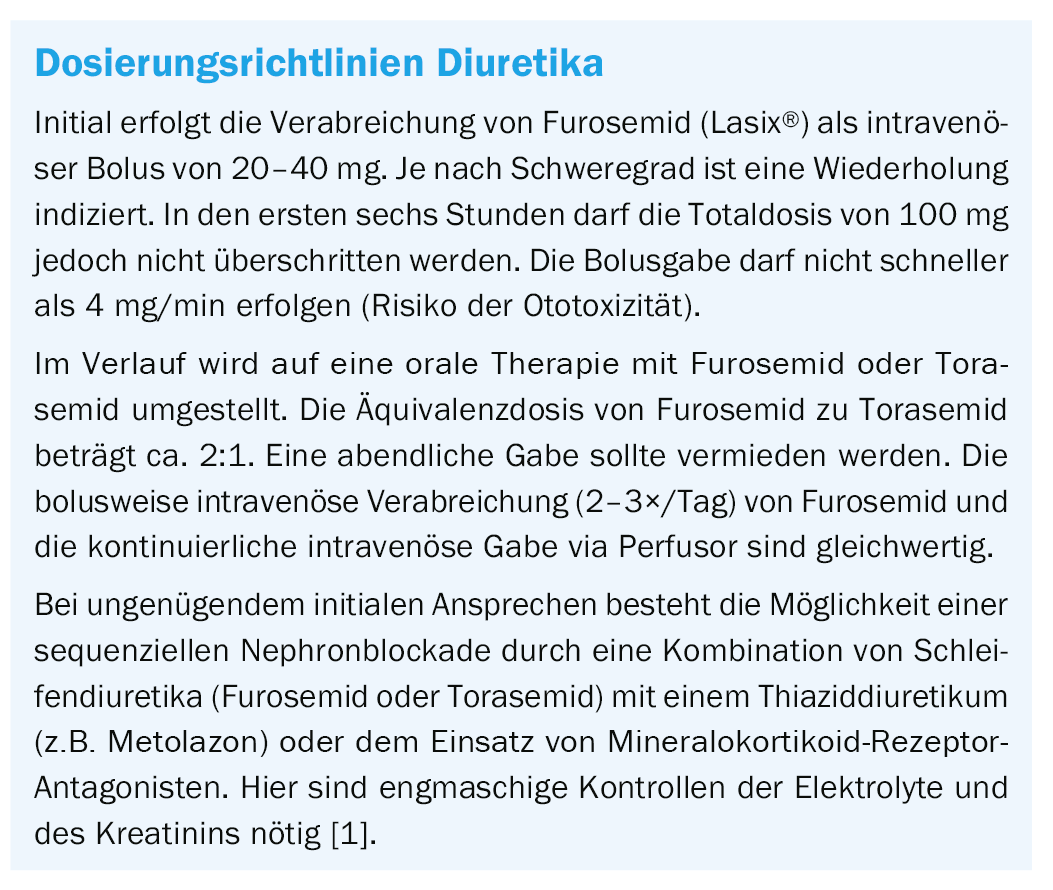

The diagnostic work-up should be started as early as possible (ideally in the prehospital phase, esp. ECG) so that causal therapy can be initiated early. The benefit of early diagnosis and therapy is well established for AHI in the context of acute coronary syndrome. In the management of AHI, diagnosis and therapy go hand in hand by systematically searching for life-threatening conditions and mechanisms and treating them as quickly as possible (Fig. 1) .

Part of the immediate work-up is also to look for alternative causes of acute dyspnea, primarily pneumonia, severe anemia, and acute renal failure. The initial diagnostic workup for suspected AHI includes the following diagnostic components, in addition to clinical assessment of the hemodynamic profile:

BNP or NT-proBNP: An AHI can be ruled out at values <100 ng/l or <300 ng/l, respectively. Elevated values are proportional to the extent of myocardial stress. The higher the natriuretic peptides, the less favorable the prognosis.

12-lead ECG: Normal ECG values make an AHI unlikely. In addition, the ECG may provide clues to the mechanism of heart failure (acute infarction, bradycardia, tachycardia).

Chest radiograph: this will indicate whether there is pulmonary venous congestion, pleural effusions, interstitial or alveolar edema, or cardiomegaly. It is also used to look for non-cardiac causes of acute dyspnea such as pneumonia or pneumothorax.

Various laboratory parameters: Using markers such as hemoglobin, TSH, CRP, creatinine, and transaminases, mechanisms and co-factors as well as effects of AHI can be studied. Cardiac troponin is also a parameter, but it must be considered as a quantitative nonspecific marker of myocardial damage and not always indicative of acute infarction.

Echocardiography: this must be performed within 24 to 48 hours in all AHI patients when cardiac pathology is unknown or inadequately known. Patients in cardiogenic shock, on the other hand, require immediate echocardiography, partly in view of mechanical problems requiring acute treatment, such as mechanical infarct complication and acute severe valvular regurgitation.

Hemodynamic profile as a starting point

If causal therapy is possible (especially in acute coronary syndrome, hypertensive emergency, tachycardia or bradycardia, acute pulmonary embolism, and mechanical complications of infarction), it should be given as early as possible. Otherwise, general supportive therapy is initiated according to the clinical and hemodynamic profile [1,4]. These supportive measures are established based on clinical experience but have no proven effect on prognosis [5]. There is still no drug whose administration in the acute phase reduces short- or long-term mortality. The goal of these measures is a rapid improvement in symptoms and clinical stabilization so that therapy for chronic heart failure can be established. Treatment modalities for AHI can be divided into acute measures, measures during hospitalization, and measures before discharge. This article focuses on the diagnosis and initial stabilizing measures during hospitalization. Depending on severity, initial treatment is provided in the emergency department/normal care unit or the emergency department/intensive care unit, with invasive monitoring if necessary.

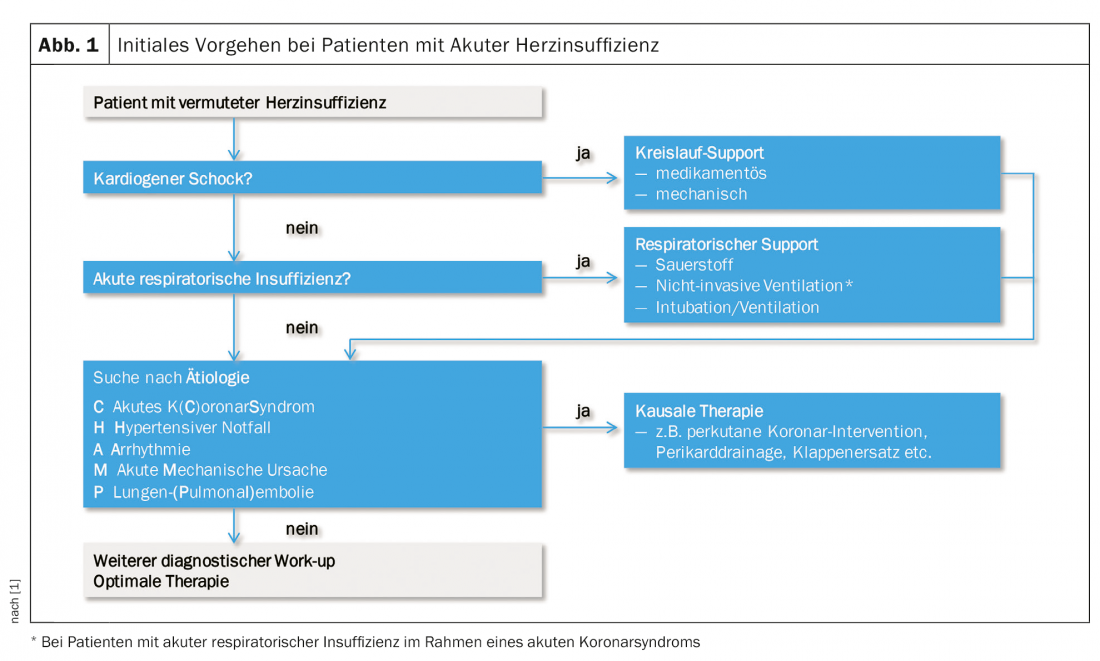

Based on hydration state (“wet” or “dry”) and tissue perfusion (“warm” or “cold,” often synonymous with normotensive vs. hypotensive), four hemodynamic profiles can be distinguished that provide the rough direction of therapy (Fig. 2).

General measures

Oxygen administration should be limited to patients with hypoxemia (SpO2 <90%). Non-invasive ventilation (CPAP/BiPAP) should be considered in cases of marked dyspnea or hypoxemia (respiratory rate >25/min, SpO2 <90%) and started as early as possible to avoid intubation. If intubation or electrocardioversion is required, caution should be exercised when sedating with propofol (risk of hypotension, cardiodepression). Sedation with midazolam is less problematic because fewer cardiac side effects are expected.

Drug therapy

In the event of an acute worsening of chronic pre-existing heart failure, pre-existing drug treatment with ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers or sacubitril-valsartan, beta blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor blockers should generally be continued. Hypotension (systolic blood pressure<85 mmHg) requires dose reduction or temporary pause of oral heart failure therapy. The following overview of heart failure drug therapy is intended as a scheme to be adapted to the individual situation of the heart failure patient.

Nitrates/vasodilators: All vasodilators have a dual effect in reducing venous (preload on the heart) and arterial (afterload reduction) tone. Vasodilators are contraindicated with systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg. Very cautious use is also indicated in cases of significant mitral and aortic valve stenosis. Continuous administration of nitrates may lead to tolerance development.

Peroral administration of nitroglycerin is initially in two 0.4 mg nitroglycerin strokes or one 0.8 mg capsule. Repetitions after 5-10 minutes are allowed, while controlling blood pressure. In the course, a change to transdermal application (5-10 mg) is possible.

Intravenous vasodilators (nitroglycerin, isosorbide dinitrate, nitroprusside, or nesiritide) are very effective in reducing dyspnea under monitoring in the intermediate care or intensive care unit in practice, although no scientific evidence is available to date [6].

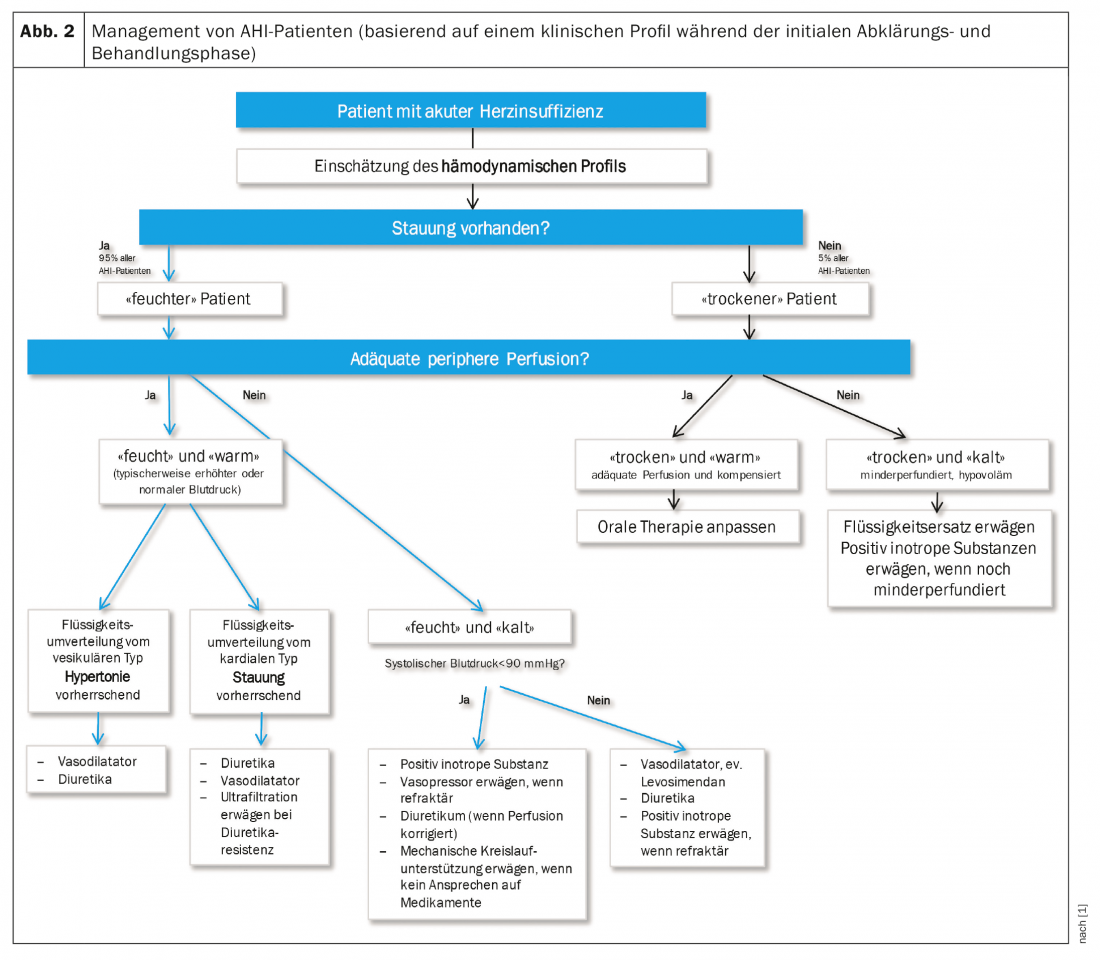

Diuretics: In current guidelines, diuretic is primary drug for treatment of AHI [7]. However, this only applies to patients with volume overload, primarily the “wet-warm” and the “wet-cold” patient if the systolic blood pressure is >90 mmHg. If primarily hypertensive derailment has led to left cardiac decompensation, the diuretic should be withdrawn in favor of the nitrate if possible.

The initial approach to treating volume overload is a combination of diuretics and vasodilators if blood pressure permits (>90 mmHg). Close monitoring of hydration status by checking clinic (i.e., jugular vein filling, pulmonary congestion, peripheral edema, body weight) and laboratory (serum potassium and creatinine) are required [6]. The box below summarizes the dosage direction lines.

Inotropics/vasopressors: drugs with pronounced peripheral vasoconstriction such as norepinephrine or dopamine in higher doses (>5 µg) may be considered for short-term use in the acute situation when tissue perfusion is insufficient despite adequate filling status to supply vital organs. However, this comes at the price of an increase in afterload as well as an increased risk of arrhythmias. As an alternative, levosimendan can be used for systolic blood pressure values >85 mmHg. Details regarding dosage can be found in the European guideline on AHI [1].

Beta-blocker/Digoxin: In the event of an acute worsening of chronic pre-existing heart failure with established beta-blocker therapy, the beta-blocker should not be completely discontinued whenever possible, but the dose should be temporarily reduced. For the treatment of acute heart failure, new beta-blocker use is indicated only in exceptional cases, such as intraventricular dynamic obstruction. Administration of a beta-blocker to control heart rate (esp. intravenously) without knowledge of LV function can cause cardiogenic shock. However, in tachycardic atrial fibrillation and preserved LV systolic function as determined by echocardiography, the beta-blocker can be administered for rate control. Digoxin is also an option for rate control in atrial fibrillation, even with impaired LVEF.

Thromboembolism prophylaxis, anticoagulation, platelet aggregation inhibition: Thromboembolism prophylaxis, primarily with a low molecular weight heparin, is clearly recommended for risk reduction of thrombosis/pulmonary embolism. For atrial fibrillation/flutter and acute coronary syndrome, the existing guidelines for anticoagulation and antithrombotic therapy apply.

Antiarrhythmic drugs/cardioversion: In the case of a predominantly tachycardia-related AHI, amiodarone, digoxin, and (if preserved LV function is known) beta-blockers can be used as antiarrhythmic drugs – in addition to electrical cardioversion. If tachycardic AF is poorly tolerated hemodynamically, it may need immediate conversion (electroconversion). Alternatively, with a view to successful electroconversion with a sustained effect during one to three days, saturation with amiodarones can be performed. Class IB/C antiarrhythmics are contraindicated in LV dysfunction [8,11].

Opiates, anxiolytics, and sedatives: opiates may be considered for cautious use in anxious patients with severe agitation and dyspnea. However, possible hypopnea must be detected early by adequate monitoring. Cautious use of benzodiazepines (diazepam, lorazepam) is an alternative to opiates in agitated patients.

Other therapy options

Renal replacement procedures: Early involvement of nephrologists is important in patients with worsening renal function in the setting of AHI. The interdisciplinary use of renal replacement is limited to “wet and warm” AHI patients who do not respond or respond inadequately to diuretic therapy. The following criteria are mentioned in the current European guidelines: Oliguria without adequate response to highest doses of diuretics, serum potassium >6.5 mmol/l, serum urea >25 mmol/l, serum creatinine >300 µmol/l and pH <7.2 [1].

Mechanical therapy options: The approach depends on the clinical situation and the postulated cause of the AHI. In case of severe ischemia with cardiogenic shock, the vessel responsible for the acute ischemia is primarily treated by percutaneous coronary intervention. Recent results show that immediate care of all coronary vessels does not improve outcome [9]. The use of circulatory support devices (intra-aortic balloon pump, ventricular assist devices) should be discussed and determined by the cardiac team with the involvement of the emergency and intensive care physicians.

The conventional indication for intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) is before surgical correction of specific acute mechanical problems (in acute severe mitral regurgitation, possibly in ventricular septal rupture) and in NSTEMI with severe 3-vessel disease in view of urgent cardiac surgery. For other causes of cardiogenic shock, there is no good scientific evidence for the benefit of IABP. Ventricular assist devices and other forms of mechanical support are used either as a “bridge-to-decision” or, in selected patients, on a longer-term basis [1]. To determine the appropriate timing of a cardiac surgical approach to endocarditis, the interdisciplinary opinion of the entire cardiac or endocarditis team must be sought early. Acute insertion of VA-ECMO in patients in cardiogenic shock, esp. after resuscitation with a relatively short “no-flow time”, should also be discussed early and in an interdisciplinary manner involving emergency and intensive care physicians.

Pleural and ascitic puncture: ple ural puncture may result in a rapid decrease in dyspnea. Ascites puncture, via a decrease in intra-abdominal pressure, may contribute to an improvement in transrenal pressure and indirectly to an improvement in renal function [10].

Take-Home Messages

- Acute heart failure is the initial manifestation of cardiac disease in approximately 20% of cases. Most often, it reflects an acute worsening of chronic heart failure.

- It is a life-threatening situation that requires rapid, structured action.

- Therapeutic measures are based on the hemodynamic profile, assessing perfusion (“warm” vs. “cold”) on the one hand and congestion (“wet” vs. “dry”) on the other.

- In patients with acute dyspnea and suspected acute heart failure, measurement of natriuretic peptides helps in the differential diagnosis. It also provides prognostic information (class IA recommendation).

Literature:

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker S, et al: 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2129-2200.

- Maeder MT, Buser M, Rickli H, et al: Heart failure with preserved left ventricular function (HFpEF). Therapeutic Review 2018; 75: 161-169.

- Ambrosy AP, Fornarow GC, Butler J, et al: The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 1123-1133.

- Nohria A, Tsang SW, Fang JC, et al: Clinical assessment identifies hemodynamic profiles that predict outcomes in patients admitted with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41: 1797-1804.

- Cheema B, Ambrosy AP, Kaplan RM, et al: Lessons learned in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Failure 2018; 20: 630-641.

- Wakai A, McCabe A, Kidney R, et al: Nitrates for acute heart failure syndromes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 8: CD005151.

- Felker GM, Lee KL, Bull DA, et al: Diuretic strategies in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 797-805.

- ERC Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015. Resuscitation 2015; 95: 1-80.

- Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, et al: one-year outcomes after PCI strategies in cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 2018; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808788 (Epub ahead of print).

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, et al: Prompt reduction in intra-abdominal pressure following large-volume mechanical fluid removal improves renal insufficiency in refractory decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail 2008; 14: 508-514.

CARDIOVASC 2020; 19(2): 12-16