The most common indications for pacing are symptomatic second- and third-degree AV blocks, a sick sinus node with symptomatic pauses, and symptomatic chronotropic incompetence. To avoid patient hazards during surgery and MRI examinations, the type and setting of the pacemaker should be known; heart failure patients also deserve special attention.

Pacemaker coding

A code informs about the global function of a pacemaker. The first coding site indicates the site of pacing: A stands for atrium, V for ventricle, and D for dual (atrium and ventricle). The second coding position indicates the place of detection (sensing), the coding is as mentioned above, 0 means here: no detection possible. The third coding site provides information about the pacemaker’s response to a detected cardiac action. I indicates that the pacemaker is inhibited by, D (dual: inhibited and triggered) that it is triggered to stimulate the ventricle in response to a detected cardiac action in the atrium, or inhibited in the presence of prior intrinsic conduction. The optional fourth coding site indicates whether a sensor is programmed into the pacemaker to increase the pacing rate under stress (R for rate-adaptive pacing). A sensor function should be programmed if the natural frequency (sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation) does not increase adequately during physical exercise. Different sensor technologies exist (piezoelectric crystal for vibration sensing, respiratory minute sensing, etc.), with the latter clearly being the more efficient.

Stimulation modes

The AAI or VVI mode means that the pacemaker can both stimulate and sense in the atrium or ventricle and, if intrinsic activity is present, is inhibited by it and does not deliver additional stimuli. With the DDD pacemaker, this applies to both ventricles.

Special functions

If a hysteresis frequency (e.g. 50/min) is programmed in addition to the basic frequency (e.g. 60/min), this means that the pulse may drop to 50/min before stimulation is performed at 60/min. This can lead to confusion, because without knowledge of a programmed hysteresis a supposed malfunction can be assumed. Hysteresis is intended to prevent stimulation during physiologically bradycardic phases.

The “mode-switch” results in an automatic mode change from DDD to DDI during atrial tachyarrhythmias (typically atrial fibrillation), thus preventing tachycardic AV sequential conduction. Without this function, as many atrial signals would be passed as the programmed upper cutoff frequency allows.

Algorithms with different names depending on the manufacturer make it possible to program the pacemaker in such a way that as much intrinsic conduction as possible takes place and thus a long PQ time does not automatically lead to pacing in the ventricle. Therefore, occasionally one can observe on the monitor or on the Holter ECG (long-term ECG) that one P wave, sometimes even two, are not transmitted and again suspect a malfunction. However, the algorithm deliberately allows such short AV blocks, as they are unlikely to cause symptoms, and as a consequence will apply a short PQ time for a period of time, usually a few minutes, thus fixedly stimulating the ventricle.

Indications for pacemaker implantation

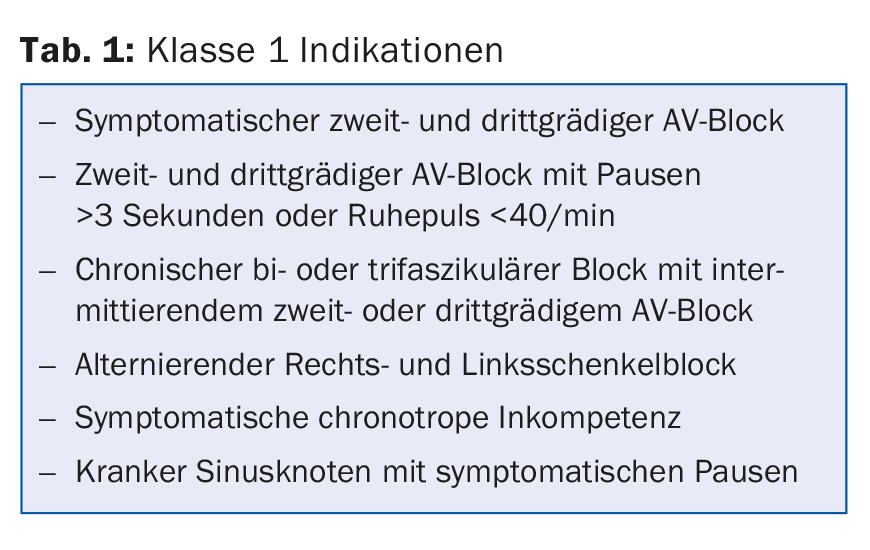

Class 1 indications are summarized in Table 1.

Follow-up/Control

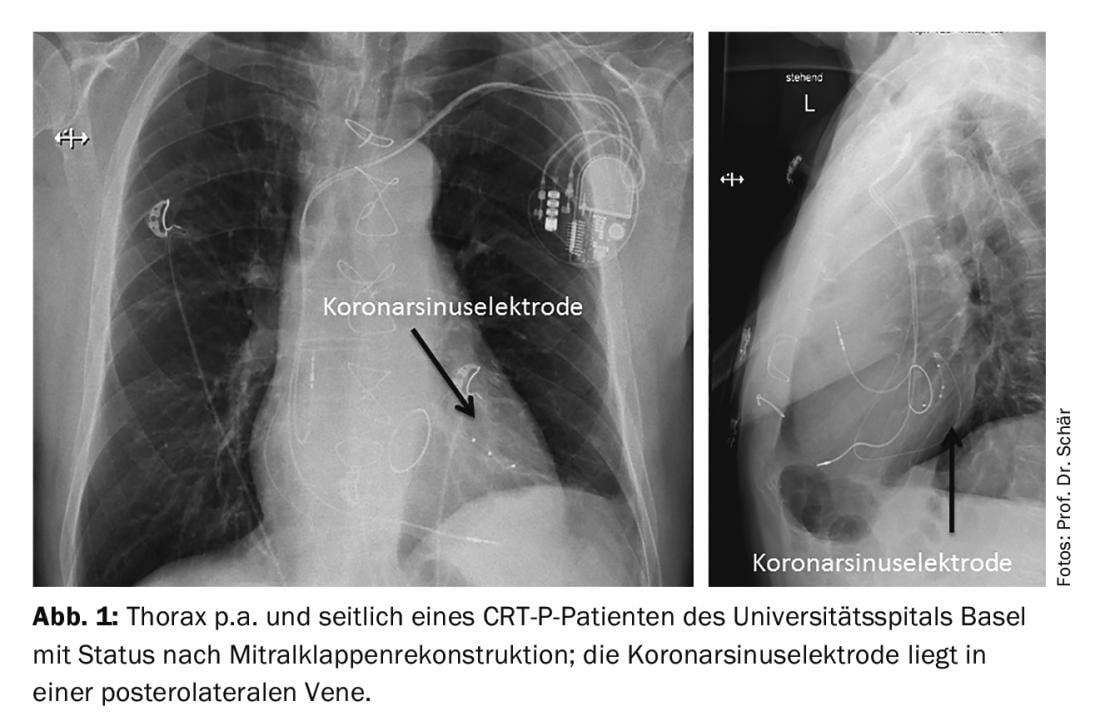

Before hospital discharge, the first pacemaker check is performed, the system integrity is verified again and the definitive parameters are set. A pneumothorax is ruled out in the p.a. and lateral chest image and the correct position of the probes is recorded (Fig. 1) . Three months postoperatively, the first follow-up is performed and the pacing values are adjusted downward. From then on, if the course is problem-free, more frequent than annual pacemaker checks cannot be justified. In addition to the respective control of system integrity (pacing, sensing, battery voltage), attention should be paid to any recorded atrial fibrillation in memory (corresponding studies on the benefit of oral anticoagulation in pacemaker-only detected, often subclinical episodes are ongoing) and the prevention of unnecessary ventricular pacing.

Today’s pacemaker batteries last at least ten years, even longer depending on the model and operating mode (pure backup or continuous pacing). When the pacemaker is replaced, the entire unit is changed, not just the battery, although the probes can almost always be left in place.

MRI examinations in pacemaker patients.

Since 2011, “MRI-safe” pacemaker systems have been approved. With such a system (pacemaker and electrodes are both “MRI safe” and from the same manufacturer), an MRI can be performed. At most, certain exclusion regions (e.g. thorax) must be considered. In any case, the pacemaker must be reprogrammed to a special MRI mode (V00 or D00) as soon as possible before the MRI. In practice, this actually means that an MRI can only be done in a hospital where a cardiologist can also reprogram the pacemaker. Due to the -00 programming, the pacemaker is, after all, blind, unable to detect intrinsic rhythm or ventricular extrasystoles (VES), stimulate the ventricle and, in extreme cases, cause torsade de pointe tachycardia.

For conventional pacemakers that are not specifically labeled as “MRI safe,” MRI examination is formally contraindicated. This is based on the concern that the magnetic fields will damage electronic components of the pacemaker and cause pacemaker dysfunction in an adverse situation. Animal studies have also shown that the temperature at the electrode tip increases 20°C during an MRI examination, which could lead to myocardial damage. However, in a recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine [1], it was shown that in 1000 patients studied with 1.5-tesla MRI, reprogramming occurred in only six cases, all of which were insignificant for pacemaker function. In patients with an intrinsic rhythm above 40/min, the pacemaker was turned off (0V0 or 0D0 mode); patients without an intrinsic rhythm were programmed into a V00 or D00 mode. It is anticipated that in the near future MRI examinations in this “off label” area will be possible at specialized centers. It should be noted that the indication for MRI should be very good, there are no alternatives to MRI, and the patient gives his “informed consent” to it. If an MRI is needed for more or less “vital” reasons, e.g. because it is essential for therapy planning, an examination should be performed despite the formal “off label” situation and the radiologists/cardiologists should be convinced accordingly.

It should also be noted that both the unit and the probes must be “MRI safe” and from the same manufacturer. For example, if a patient’s old pacemaker is replaced with an “MRI-safe” pacemaker due to battery depletion, an MRI still cannot be formally performed. Also, if “old” electrodes that are no longer used are in the heart, no MRI is formally possible.

Perioperative pacemaker conversion

During surgery, unipolar cautery may interfere with the pacemaker (the pacemaker misrecognizes the cautery signals as cardiac action and thus does not stimulate). In extreme cases, this would lead to asystole in a completely pacemaker-dependent patient for as long as chewing. Whether there is a risk for this interference depends very much on the location of the cautery; cautery on the leg is unlikely to ever cause interference. Moving every single pacemaker before every operation is logistically impossible, error-prone and, above all, very rarely really medically necessary.

Therefore, the current guidelines of the Working Group on Pacemakers and Electrophysiology of the SGK [2] primarily recommend that a magnet be available in the operating room. If interference occurs, this can be placed on the pacemaker, which immediately switches to -00 mode and thus becomes blind to the cautery artifacts. Only in pacemaker-dependent patients should the magnet be fixed over the pacemaker throughout the operation. If this procedure is technically not possible during surgery (prone position, surgery in the immediate vicinity of the pacemaker), the pacemaker must be repositioned preoperatively. However, this is probably only necessary for every 300-500th procedure.

Postoperative control is only performed if a malfunction was suspected intraoperatively.

Biventricular pacing (cardiac resynchronization therapy, CRT)

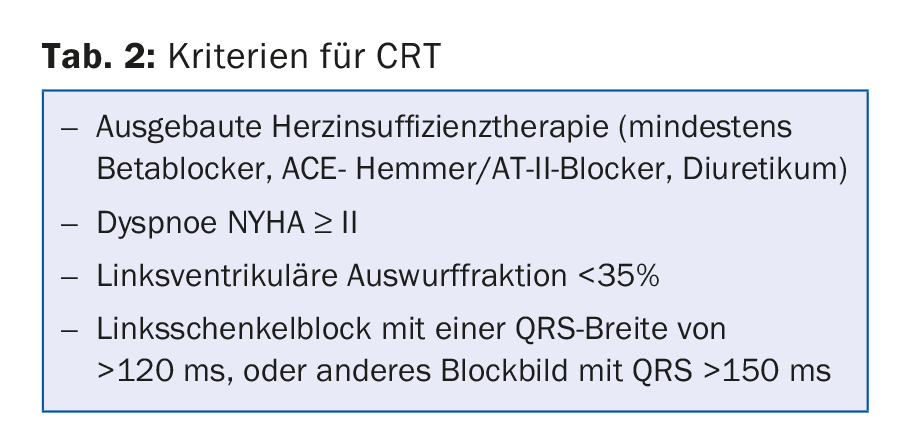

In heart failure patients, biventricular pacing has been shown to be useful in selected situations in addition to optimal heart failure drug therapy. Suitable patients have an LVEF of <35% and “ideally” have left bundle branch block (Table 2). Indeed, subanalyses of MADIT-CRT [3] have shown no benefit of CRT in patients with QRS widening of other types. CRT is thus applied here without a classic pacemaker indication. In addition, a study [4] has also been able to show that in patients with only mildly impaired LVEF and high right ventricular (RV) pacing demand (usually with complete AV block), a priori CRT resulted in at least a reduction in hospitalization. However, this indication is rarely used in clinical practice in Switzerland at the moment.

The pathophysiological background of biventricular pacing is the dyssynchrony in contraction of the two ventricles caused by delayed intraventricular conduction of excitation. This compromises diastolic ventricular filling, resulting in a drop in cardiac output. Isolated right ventricular pacing further worsens hemodynamics; ideally, this is compensated for by simultaneous pacing of both ventricles.

Women in general, patients with nonischemic cardiopathy, wide QRS complex, and significant symptomatology have been found to benefit most from resynchronization therapy.

Take-Home Messages

- The most common indications for pacing are symptomatic second- and third-degree AV block, a sick sinus node with symptomatic pauses, and symptomatic chronotropic incompetence.

- Usually, inspections take place once a year.

- Perioperatively, a pacemaker has to be repositioned only in selected cases (surgery in prone position or very close to the pacemaker).

- For an “MRI-safe” pacemaker, both the unit and the probes must be MRI-safe and from the same manufacturer.

- In heart failure patients with LVEF <35% and left bundle branch block, biventricular pacing (CRT) can help improve symptoms and quality of life.

Literature:

- Russo RJ, et al: Assessing the Risks Associated with MRI in Patients with a Pacemaker or Defibrillator. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(8): 755-764.

- www.pacemaker.ch/download/checklist_de.pdf

- Goldenberg I, et al: Survival with cardiac-resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(18): 1694-1701.

- Curtis AB, et al: Biventricular pacing for atrioventricular block and systolic dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(17): 1585-1593.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(2): 12-14