Genital warts (condylomata acuminata) are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) and are the most common sexually transmitted disease worldwide. Approximately 90% are caused by the low-risk HPV types 6 and 11. In risk groups, there is sometimes a dysplasia rate of 18-60%. In addition to therapeutic options, vaccination is an important contribution to the eradication of the disease.

Genital warts (condylomata acuminata) are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) and are the most common sexually transmitted disease worldwide, with a marked increase in incidence in recent decades. The disease mainly affects sexually active people between the ages of 15 and 45. In Europe alone, approximately 300,000 new cases of the disease are counted each year.

Pathogen

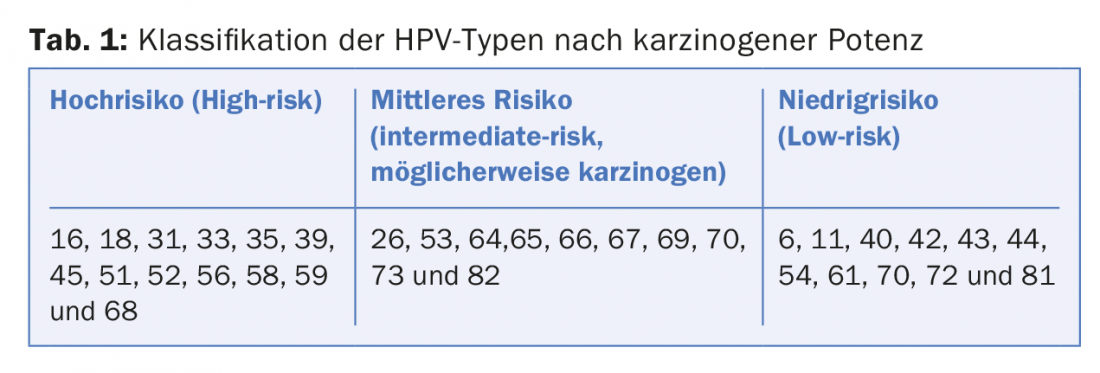

Genital warts are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), a non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus from the Papillomaviridae family. Approximately 120 different types have been described, which are classified into low-risk and high-risk types based on their oncogenic potency. Approximately 40 of these HPV types predominantly infect the anogenital skin and mucosa, with approximately 13 HPV types considered high-risk types (Table 1) . Infection of epithelial skin and mucosal cells induces uncontrolled tumor-like growth. Genital warts are caused by low-risk types 6 and 11 in about 90% of cases.

Genital warts and dysplasia development

In most cases, infection occurs during sexual contact through direct skin or mucosal contact. Because the virus is resistant to desiccation, it can also be passed on through hands and contaminated surfaces (sex toys). Also, microlesions caused, for example, by intimate shaving and during sexual intercourse, favor the development and spread of condylomas. The incubation period ranges from three weeks to up to eight months.

The probability of getting an infection in the course of life is 60-80%. The subclinical infection rate is estimated to be as high as 40%. Symptoms may not appear until years after infection. In approximately 90% of cases, the virus is eliminated by the immune system within six months to two years.

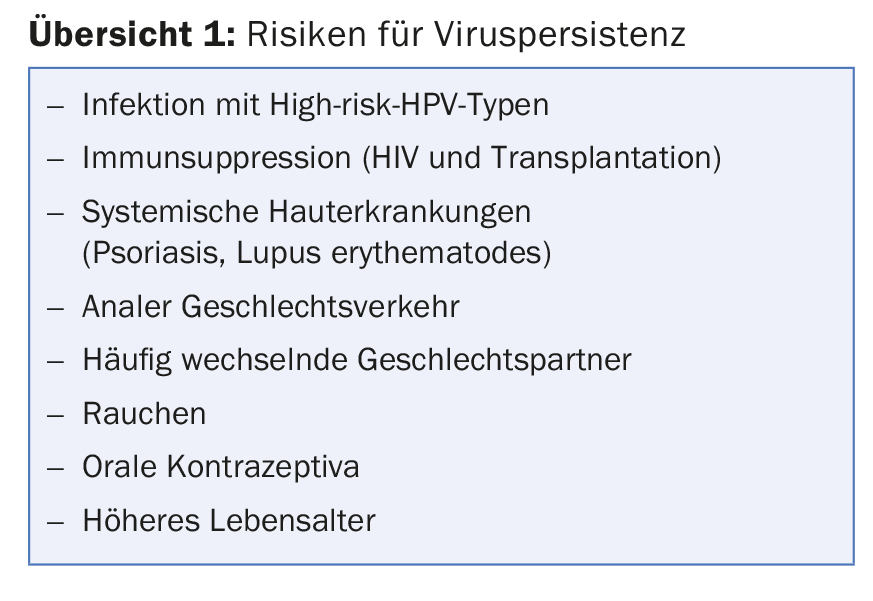

However, if persistent infection occurs, dysplasia (intraepithelial neoplasia) or carcinoma may develop in addition to genital warts (overview 1) . This is also true in the case of infection by primary low-risk HPV types.

Risk groups

A significant risk group with a high HPV prevalence are HIV-positive homosexual men (MSM, male sex with men). Genital warts show a higher high-grade dysplasia rate of 18-60% in this patient population. Furthermore, in HIV-positive MSM, endoanal condylomas also have proportions of high-grade dysplasia in up to 20%.

Another risk group for anal or genital dysplasia is women who have ever had a pathologic cervical Pap smear. The likelihood of having concurrent anal and cervical HPV infection was 50% in women who had CIN 2+. Also, women who had condylomas showed a fourfold increased risk of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Symptoms and clinical presentation

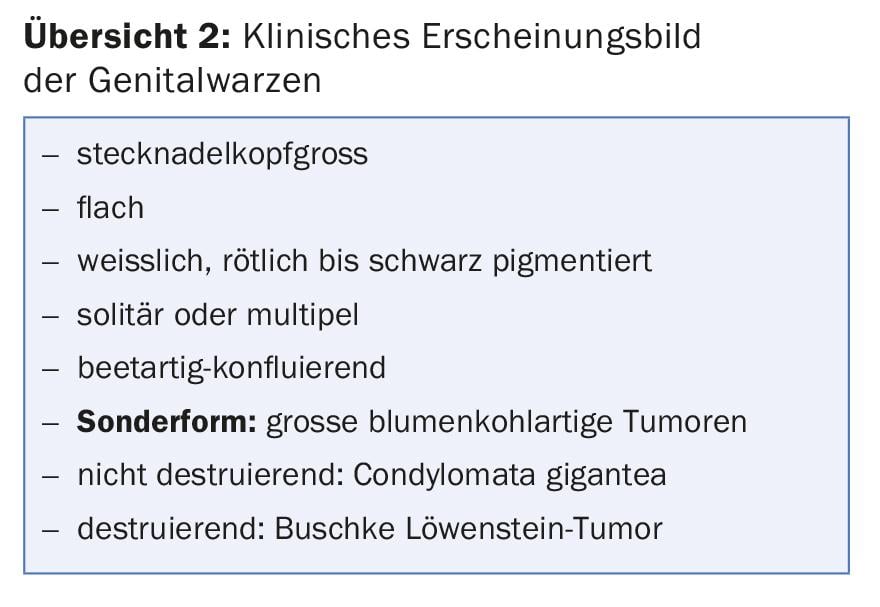

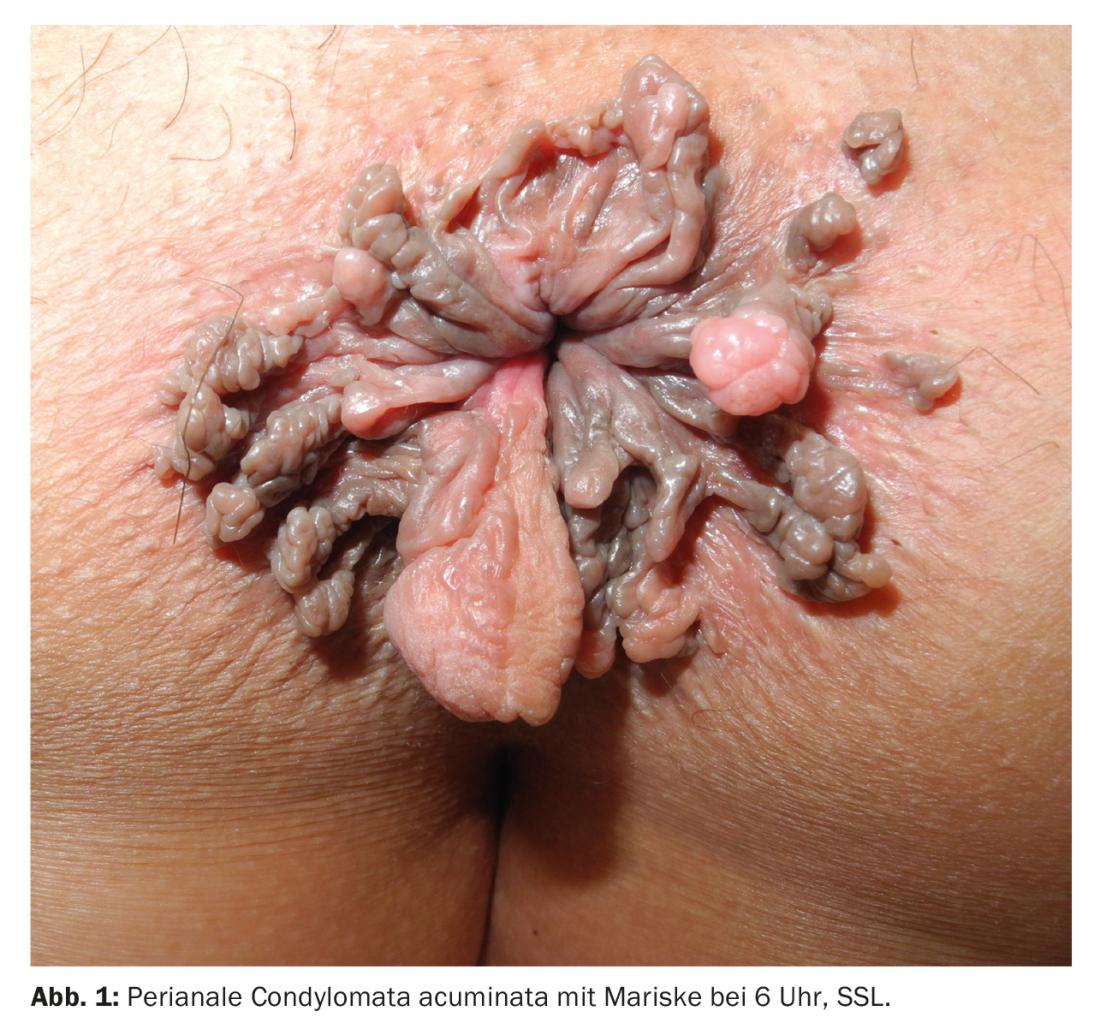

The symptoms, as well as the appearance of genital warts, can vary greatly depending on their location in the genital area (overview 2). Genital warts do not cause typical symptoms. They become symptomatic only when they ooze, burn, cause itching or easy bleeding, and multiple tumors appear perianally, impairing anal hygiene (Fig. 1).

Diagnostics and screening

The diagnosis of warts in the external genital area usually corresponds to a visual diagnosis. Diagnosis of vaginal or endoanal/rectal condylomas requires speculum examination or proctoscopy/rectoscopy. High-resolution anoscopy (HRA) is essential for the diagnosis of anal dysplasia (Fig. 2 and 3). Only 40% of anal dysplasias can be detected with the naked eye. Together with histopathological examinations, HRA has high sensitivity and good specificity and has become the gold standard in recent years.

An international standard for screening programs of the anal region does not yet exist. However, it has been shown that at-risk groups benefit from screening by cytologic smear and HRA. In addition, increased biopsies of genital warts and close follow-up with HRA should be performed in this patient population. Ablative therapy for condylomas should be undertaken if anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) is present. Apart from high-risk groups, a large 2012 Danish study showed that patients with genital warts generally have an increased risk of developing anogenital carcinomas in the longer term.

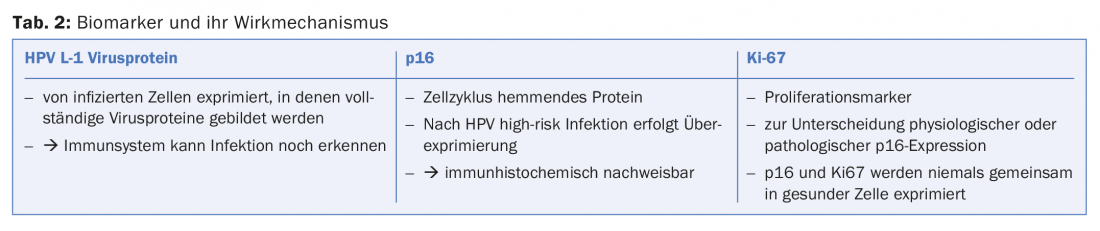

Other important methods used in histopathological and cytopathological examinations include polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for virus typing and the determination of biomarkers such as HPV L-1, p16, and Ki-67. These biomarkers provide information on whether high-grade dysplasia is present and whether the HPV infection has an increased potential for progression (Table 2, Fig. 4).

Therapy

Genital warts show spontaneous remission in up to 30%. Therapy is based on the location and extent of the genital warts, but also on the patient’s risk profile, wishes and compliance. In most cases, therapy is recommended to prevent further spread.

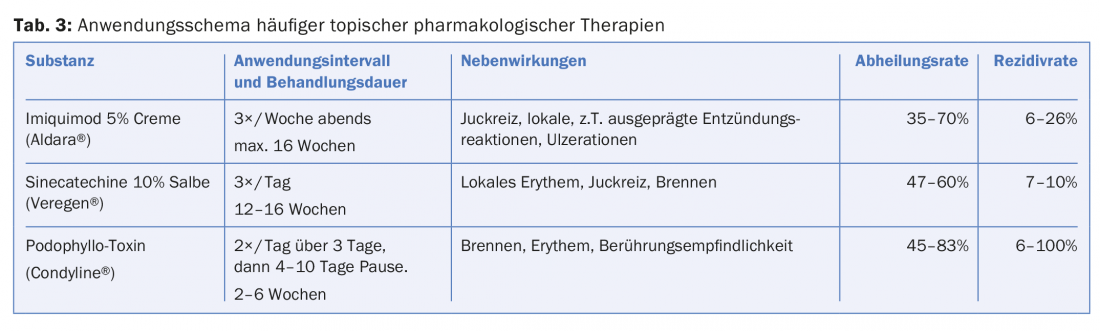

Possible therapeutic measures to eradicate condylomas range from topical application of ointments, to cryotherapy, to surgical resection procedures (Table 3).

Cryotherapy represents an outpatient ablation procedure that is efficient but usually requires several therapy sessions. The cure rate is 44-75%, and the recurrence rate is 25-40%.

In case of extensive peri- and endoanal involvement or if the condyloma is present in the urethra, removal should be performed by surgical measures (electroresection, scissor resection, laser ablation) under local or general anesthesia. The healing rate is 90-100% in all procedures, with a recurrence rate of 20-30%.

Vaccination

Two vaccines (Gardasil 4® and Cervarix®) are currently available in Switzerland. Cervarix® was introduced in 2007 and is directed only against virus types 16 and 18. Gardasil® is a quadruple vaccine against virus types 6, 11, 16 and 18. Gardasil 9® was also introduced in the EU in 2015. Approval in Switzerland has not yet been granted. Vaccination with Gardasil 4® has already been carried out in Switzerland since 2006 and is recommended by the Federal Office of Public Health and the Federal Commission for Vaccination Issues for all adolescents aged 11-14 years with two vaccination doses at intervals of six months, in girls as a basic vaccination, in boys as a supplementary vaccination. In the 15- to 26-year-old age group, vaccination is recommended as a catch-up or supplemental vaccination and requires three doses at zero, two and six months apart. Since July 2016, the vaccination is also covered by health insurance for men up to 26 years. Protection is highest if vaccination is given before first sexual contact.

Since its introduction, more than 170 million HPV doses have been applied worldwide. In large clinical trials (FUTURE I and II), there was a 99 percent reduction in the incidence of genital warts in women aged 15-26 years, provided there had been no infection prior to vaccination.

In countries such as Australia, which introduced universal vaccination programs in schools starting in 2007 and achieved high vaccination rates of over 75%, a 92% reduction in genital warts was shown in women <21 years. Although men in Australia were not vaccinated until 2013, this also showed an 81% decrease in genital warts in the same age group. This suggests stove immunity.

The question remains as to whether patients older than 26 years of age or who already have condylomas or intraepithelial neoplasia should be vaccinated. In this regard, studies have shown that individuals vaccinated after therapy for HPV lesions have a significantly lower risk of recurrence.

Take-Home Messages

- Genital warts are the most common sexually transmitted disease worldwide.

- HPV types 6 and 11 cause 90% of genital warts.

- High-risk groups show increased rates of dysplasia of genital warts.

- Vaccination leads to a 90 percent decrease in incidence.

Further reading:

- Yanofsky VR, Patel RV, Goldenberg G: Genital Warts A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2012; 5(6): 25-36.

- Kreuter A, et al: High-grade dysplasia in anogenital warts of HIV-positive men. JAMA Dermatol 2016; 152(11): 1225-1230.

- Wieland U, Kreuter A: Genital warts in HIV-infected individuals. Dermatologist 2017; 68(3): 192-198.

- Siegenbeek van Heukelom ML, et al: Low- and high-risk human papillomavirus genotype infections in intra-anal warts in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175(4): 735-743.

- Metcalf AM, Dean T: Risk of dysplasia in anal condyloma. Surgery 1995; 118(4): 724-726.

- Blomberg M, et al: Genital Warts and Risk of Cancer: A Danish Study of Nearly 50 000 Patients With Genital Warts. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2012; 205(10): 1544-1553.

- Lacey CJ, et al: European guideline for the management of anogenital warts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013; 27(3): e263-70.

- Ali H, et al: Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ 2013; 346: f2032.

- Lee LY, Garland SM: Human papillomavirus vaccination: the population impact. F1000Res 2017; 6: 866.

- Joura EA, et al: Effect of the human papillomavirus (HPV) quadrivalent vaccine in a subgroup of women with cervical and vulvar disease: retrospective pooled analysis of trial data. BMJ 2012; 344: e1401.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(6): 15-18