Overall survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia cannot be altered by optimizations of imatinib therapy. This is despite the fact that earlier evaluations were able to demonstrate an influence on the response.

Imatinib has revolutionized the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Survival rates have risen sharply as a result. Patients who respond to TKIs now have near-normal life expectancy. Researchers are therefore now concerned with the question of whether the usual dose of 400 mg is suitable for all patients to achieve an optimal outcome. Several studies are investigating the potential benefit of modified imatinib therapy. Approaches with high-dose (800 mg) or dose-adapted imatinib (or also the combination with interferon) may indeed change the response compared with the standard variant, Hehlmann and colleagues previously showed [2,4] (albeit partly contradicting other randomized studies [3]). But does this benefit translate into better, i.e. longer, survival in the long run? So can higher survival rates ultimately be achieved with different treatment optimizations?

The CML IV study

This question was addressed, among others, by the large randomized CML IV trial – with Swiss participation. The aim was to investigate to what extent the standard therapy with 400 mg/d imatinib can be optimized. For this purpose, 1551 newly diagnosed patients in the chronic phase were randomized into five arms. Two arms, those testing imatinib in combination with cytarabine or after failure of interferon, were closed to further patient recruitment after a pilot phase. The remaining three consisted of the standard dose of 400 mg/d, high-dose therapy at 800 mg/d, and the combination of imatinib with interferon. The median age of the patients was 53 years and 61% were male.

At the EHA Congress in Madrid, the long-term survival data were discussed, more specifically the overall survival after a median observation period of 9.5 years. It was 82% across all groups (progression-free survival 80%).

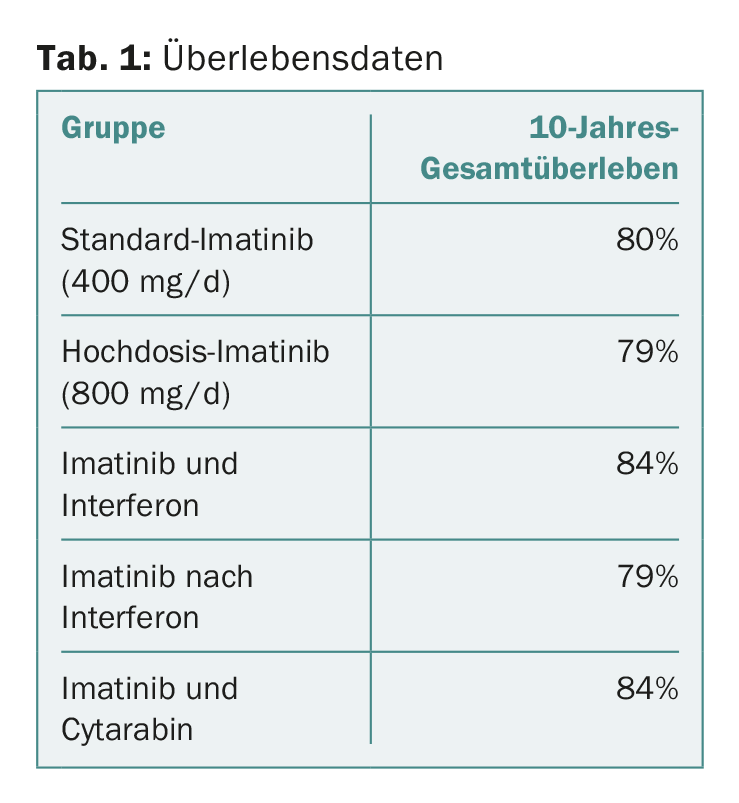

Survival after a decade

The details for each group are shown in Table 1. The results show that there were no significant differences between the different approaches or treatment optimizations. This is despite the fact that a faster response was achieved with high-dose therapy, as shown by previous publications [2]. However, what did play a role in long-term survival was the achievement of molecular response milestones at three, six, and twelve months, also consistent with previously published data from the study [2,4]. In the multivariate analysis, comorbidities and smoking status also emerged as relevant factors influencing survival. Whether the treatment center was academic or not also played a significant role-but the sex of the patient did not.

Has the end of the line been reached?

CML IV has consequently shown: Survival rates of CML patients on imatinib are high and not necessarily influenced by an initial treatment regimen with faster response, but rather by external factors such as smoking, type of treatment center, and patient comorbidities.

The risk of dying after ten years from CML-independent parameters rather than the disease itself was significantly greater for the participants, namely twice as high – ultimately an effect to be expected with well-performing drugs [5]. In addition, the European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) long-term survival score, which evaluates CML-associated mortality risk, was also a significant predictor of prognosis: high-risk groups survived for less time than low-risk groups.

So, on the one hand, survival is independent of time to response (at least in this study and treatment setting or observation duration). Therefore, high-dose therapy did not cause a significant difference. I.e., conversely, time to response is not a suitable surrogate marker for overall survival. On the other hand, it should not be forgotten that the achievement of the target values in the molecular response at certain time points certainly and as expected played a role in the prognosis. Patients with BCR-ABLIS <1% at six months had a 5-year survival of 97% versus 89% with BCR-ABLIS >1% (p<0.001) [6].

Overall survival suitable as an indicator of success of a therapy?

The EHA presentation thus leaves one somewhat perplexed. Although more patients achieve a response (faster) under the higher dose and this is associated with better overall survival, the differences between the dose variants do not appear to have a significant long-term impact: All live the same length of time regardless of which imatinib regimen they received. Other factors not directly related to CML become more important: Is the patient otherwise healthy? Does he smoke?

One can also formulate the whole thing the other way around: Overall survival may not be suitable for evaluating the long-term success of specific CML treatments [5]. If this were the only approach, the end of the line would be reached with imatinib at the standard dose.

Of course, endpoints such as achieving a deep response to perhaps even be able to discontinue the TKI (see EURO-SKI study [7] with update at last year’s EHA congress [8]), or protection against progression also play a central role for patients with CML and must not be forgotten in this context.

Source: European Hematology Association (EHA) 2017 Congress, June 22-25, 2017, Madrid.

Literature:

- Hehlmann R, et al: Assessment Of Imatinib 400mg As First Line Treatment Of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: 10 -Year Survival Results Of The Randomized Cml Study IV. EHA 2017; Abstract S424.

- Hehlmann R, et al: Deep Molecular Response Is Reached by the Majority of Patients Treated With Imatinib, Predicts Survival, and Is Achieved More Quickly by Optimized High-Dose Imatinib: Results From the Randomized CML-Study IV. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2014; 32(5): 415-423.

- JE Cortes, et al: Phase III, randomized, open-label study of daily imatinib mesylate 400 mg versus 800 mg in patients with newly diagnosed, previously untreated chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase using molecular end points: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor optimization and selectivity study. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 424-430.

- Hehlmann R, et al: Tolerability-Adapted Imatinib 800 mg/d Versus 400 mg/d Plus Interferon-α in Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011; 29(12): 1634-1642.

- Saussele S, et al: Impact of comorbidities on overall survival in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: results of the randomized CML study IV. Blood 2015; 126(1): 42-49.

- Hanfstein B, et al: Early molecular and cytogenetic response is predictive for long-term progression-free and overall survival in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Leukemia 2012; 26(9): 2096-2102.

- Mahon FX, et al: Interim Analysis of a Pan European Stop Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Trial in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: The EURO-SKI study. Blood 2014; 124: 151.

- Richter J, et al: Stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitors in a very large cohort of European chronic myeloid leukemia patients: results of the EURO-SKI trial. EHA 2016; Abstract S145.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(4): 7-8.