The type and duration of combined antithrombotic therapy vary. Decisive factors are the clinical setting (stable CHD vs. ACS), the need for additional anticoagulation (e.g., atrial fibrillation), and the patient-specific bleeding risk. Secondary prevention is an integral part of management after revascularization.

Autumn 2017 will mark the 40th anniversary of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which was first successfully performed by Andreas Grüntzig at the University Hospital Zurich in 1977 [1]. Since then, the method has continuously improved, especially with the use and further development of coronary stents with a gradual decrease in periprocedural risks [2]. In addition to optimal healing in the catheterized coronary segment (by avoiding stent thrombosis [ST] and instent restenosis [ISR]), adequate secondary prevention and possible drug treatment of residual pectanginal symptoms are crucial for the longer-term course [3].

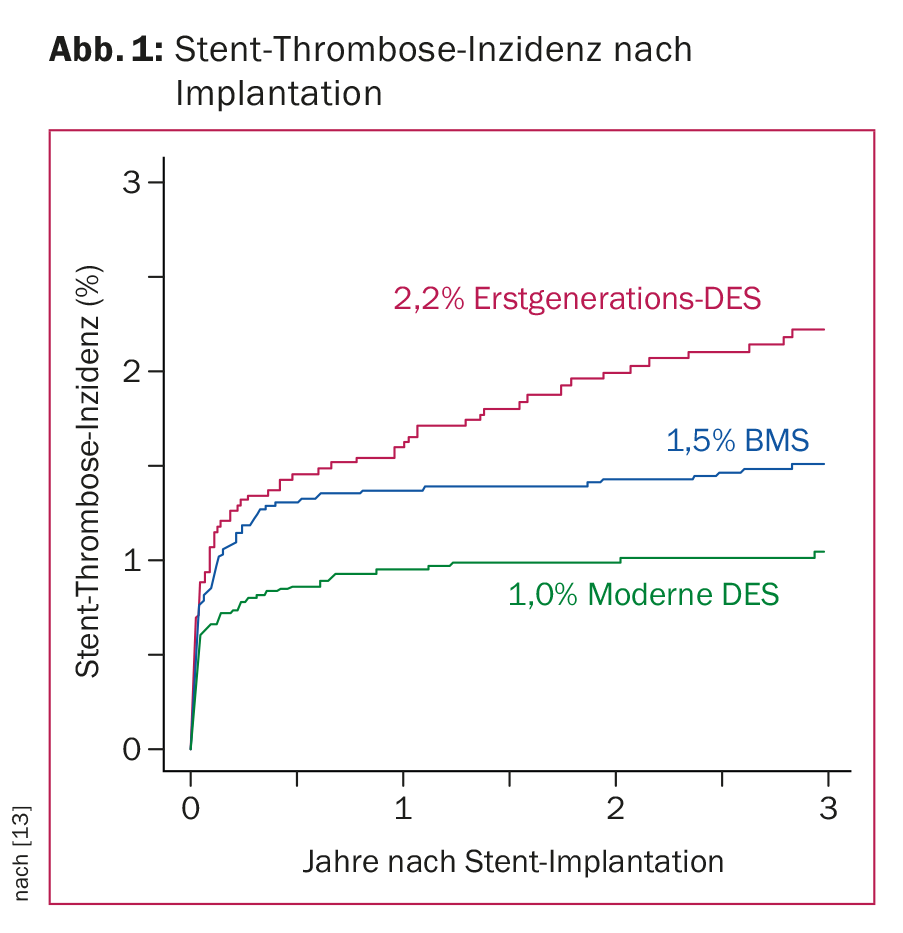

Superiority of modern drug-eluting stents (DES)

The excellent results achieved by current stent technology are based on advances in pharmacotherapy and device innovation combined with optimal implantation techniques [4]. Prevention of ISR and ST is essential. Recent registry and comparative studies with modern DES in representative patient populations show their superiority over bare metal stents (BMS) with an average ST rate of less than 1% within the first year after stent implantation and 0.2-0.4% annually thereafter. (Fig. 1). With modern DES, clinically manifest ISR occurs in less than 5% of cases. Due to the optimal data situation of modern DES, uncoated stents (BMS) are implanted in Switzerland nowadays only in rare cases. New developments such as the use of drug-eluting balloons or resorbable so-called scaffolds (i.e., stent scaffolds that dissolve over time) are promising, but they remain reserved for specific patient populations for the time being given the still limited data available.

Antithrombotic therapy

The choice or combination of antithrombotic therapy depends primarily on the clinical setting (stable coronary artery disease (CAD), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)). Ultimately, the goal is to find a combination of the lowest possible risk of ischemia and bleeding. The indication for gastroprotection during combined antithrombotic therapy is generous (age 65 years or older, history of previous gastrointestinal bleeding, combination with steroids). When using clopidogrel, omeprazole should be avoided because of interaction potential.

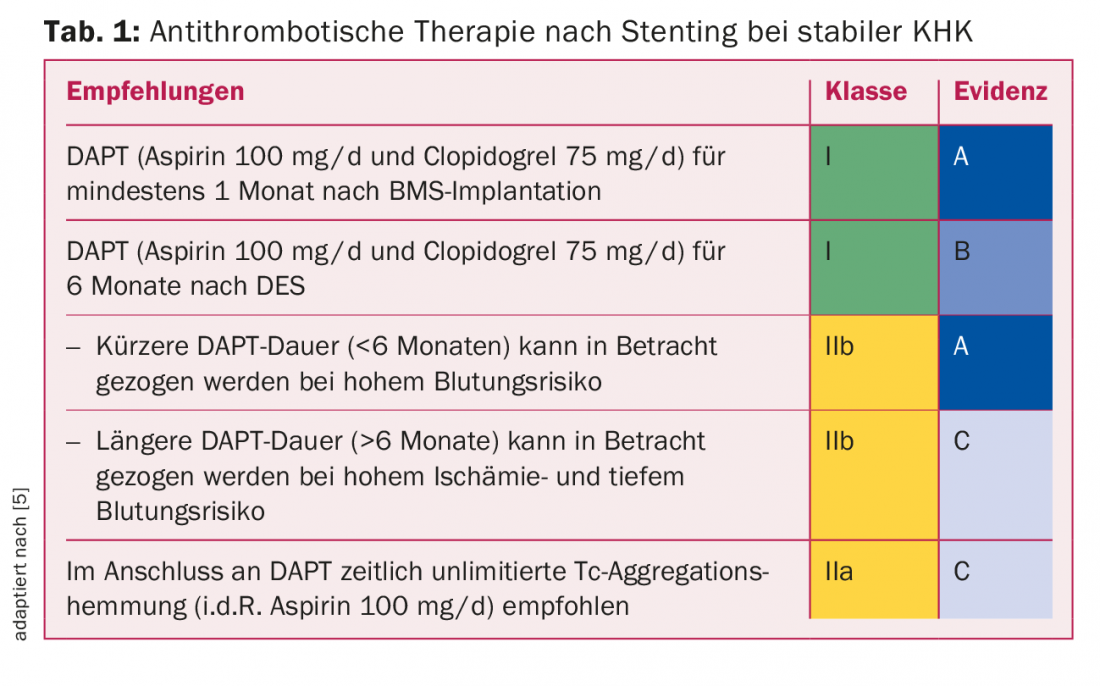

Platelet aggregation inhibition in stable CHD: For PCI with stent implantation in stable CHD, data exist mainly with the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel. Table 1 shows the current guidelines valid in Switzerland based on the European guidelines [5]. Because of the relatively frequent occurrence of very late ST, a duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (“DAPT”) of 12 months has been recommended for first-generation DES until a few years ago. However, vascular endothelialization in modern DES is already complete a few months after stent implantation, which is why six months of DAPT is usually absolutely sufficient. Any adjustment to this DAPT duration is determined by the interventional cardiologist at the time of stent implantation: an extension to 12 months for complex lesions, a reduction to one to six months for very high bleeding risk.

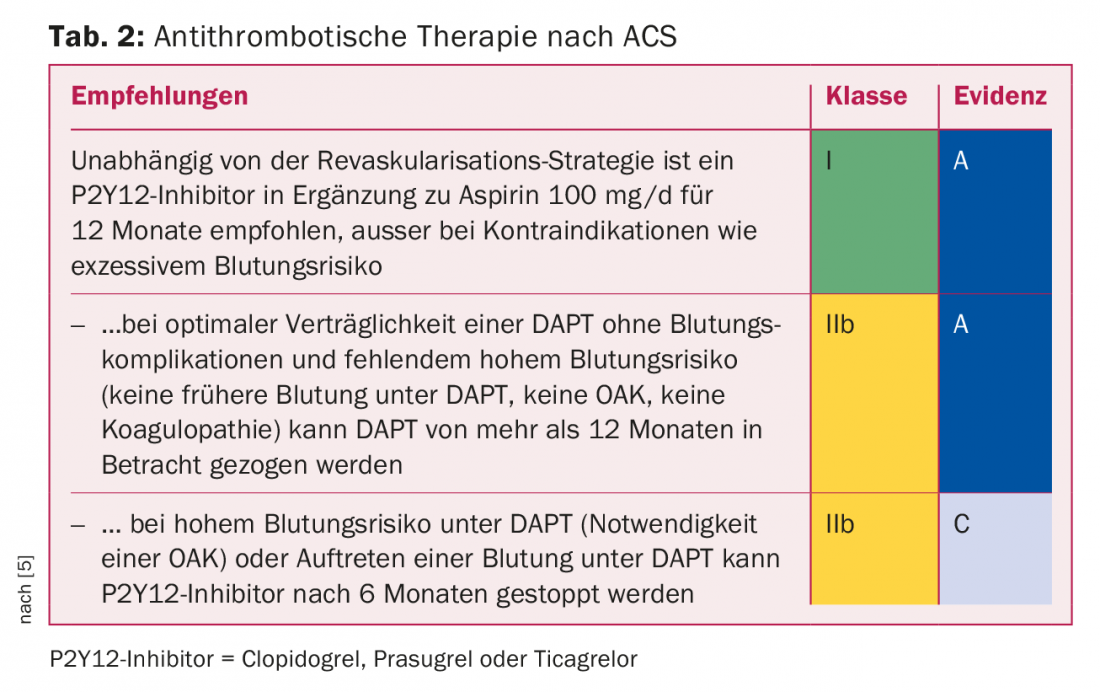

Platelet aggregation inhibition after acute coronary syndrome (ACS): The risk of ischemia remains elevated for several years (Tab.2). The large comparative studies between prasugrel and clopidogrel [6] on the one hand and between ticagrelor and clopidogrel [7] on the other hand, performed in ACS patients in the first 12 months after ACS, have shown a significant reduction in myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death with prasugrel and ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel. Due to the lack of direct comparative studies between ticagrelor and prasugrel, no clear statement can be made regarding the different efficacy of the two substances. The PLATO study, conducted as an “all-comers study” with ticagrelor, allows transfer to all ACS patient collectives; the TRITON study, conducted with prasugrel, is a pure PCI study and therefore does not allow transfer to a conservatively treated ACS collective. Considering the contraindications (acute hemorrhage, st. n. intracranial hemorrhage, moderate to severe hepatic insufficiency) and side effects (dyspnea), ticagrelor offers itself as the drug of first choice for all ACS patients.

Another question is “ACS: DAPT for more than 12 months?” Cardiovascular risk remains higher than average in the years after ACS, primarily due to general progression of coronary atheromatosis with plaque ruptures or newly emerging relevant stenoses elsewhere in the coronary system [8].

Approximately half of all cardiovascular recurrence events occur because of a new lesion. Not unexpectedly, the PEGASUS trial, conducted with ticagrelor (2× 60 mg vs. 2× 90 mg vs. placebo), showed a significant reduction in cardiovascular events (absolute risk reduction just under 2%, number needed to treat 70) with ticagrelor – at the price of more nonfatal, mainly gastrointestinal bleeding.

What to make of new scores for risk stratification regarding bleeding (www.precisedapt.com)? Easy-to-use internet- or app-based clinical scores allow to identify high-risk patients with anamnestic and clinical parameters on an individual level with corresponding DAPT duration shortening in case of high bleeding risk and with normal (or longer) DAPT duration in case of “non-high” bleeding risk [9]. However, validation for clinical use is still pending.

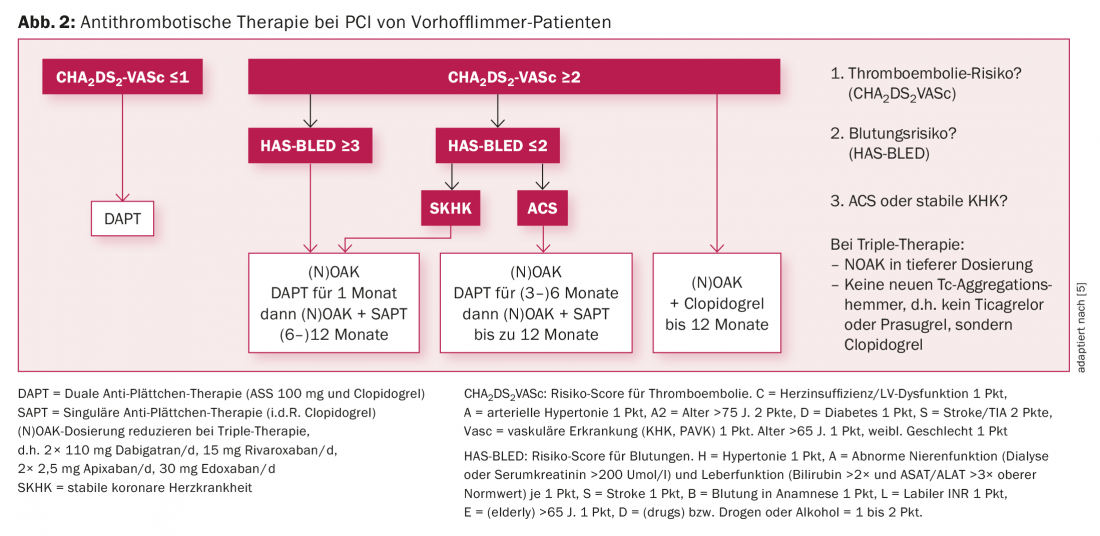

Atrial fibrillation and PCI (Fig. 2): Atrial fibrillation is a common comorbidity in CHD patients, especially in the elderly [10]. Accordingly, the question of combining antiplatelet and plasmatic anticoagulation arises during and especially after PCI. The advantages of NOAKs shown from the large atrial fibrillation trials with less (especially intracranial) bleeding compared with VKAs can be transferred to the collective of CHD patients with atrial fibrillation on the basis of subanalyses. However, there is also a balancing act between prevention of ST/stroke on the one hand and bleeding on the other. With guidelines established for several years, it is important to determine the type and duration of combination therapy based on the risk of bleeding and thromboembolism estimated with scores and on the individual CHD situation, involving the follow-up treatment teams in the decision.

The recent Pioneer ACS trial confirmed that dual therapy with rivaroxaban 15 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg or the combination with very low rivaroxaban dose (2× 2.5 mg/d plus aspirin 100 mg/d plus clopidogrel 75 mg/d) compared with conventional triple therapy is associated with a lower risk of bleeding with a likely unchanged low rate of stent thrombosis and stroke [11].

In summary, in the atrial fibrillation collective with PCI, individualization of antithrombotic therapy based on the individual risk for bleeding and stent thrombosis must occur. Combination of ticagrelor or prasugrel with (N)OAK is not allowed. If triple therapy is required, clopidogrel should be used instead of ticagrelor or prasugrel.

Antiischemic therapy

In the event of incomplete revascularization or recurrence of angina, anti-ischemic drug therapy should be continued or re-established. The principles of individualized therapy in principle and the question of (re)invasive assessment are based on the one hand on the effectiveness of the measure in reducing symptoms and on the other hand on the potential prognostic benefit [12]. Antianginal drugs that do not improve the prognosis, such as nitrates, should generally be discontinued when symptoms are relieved.

Secondary prevention

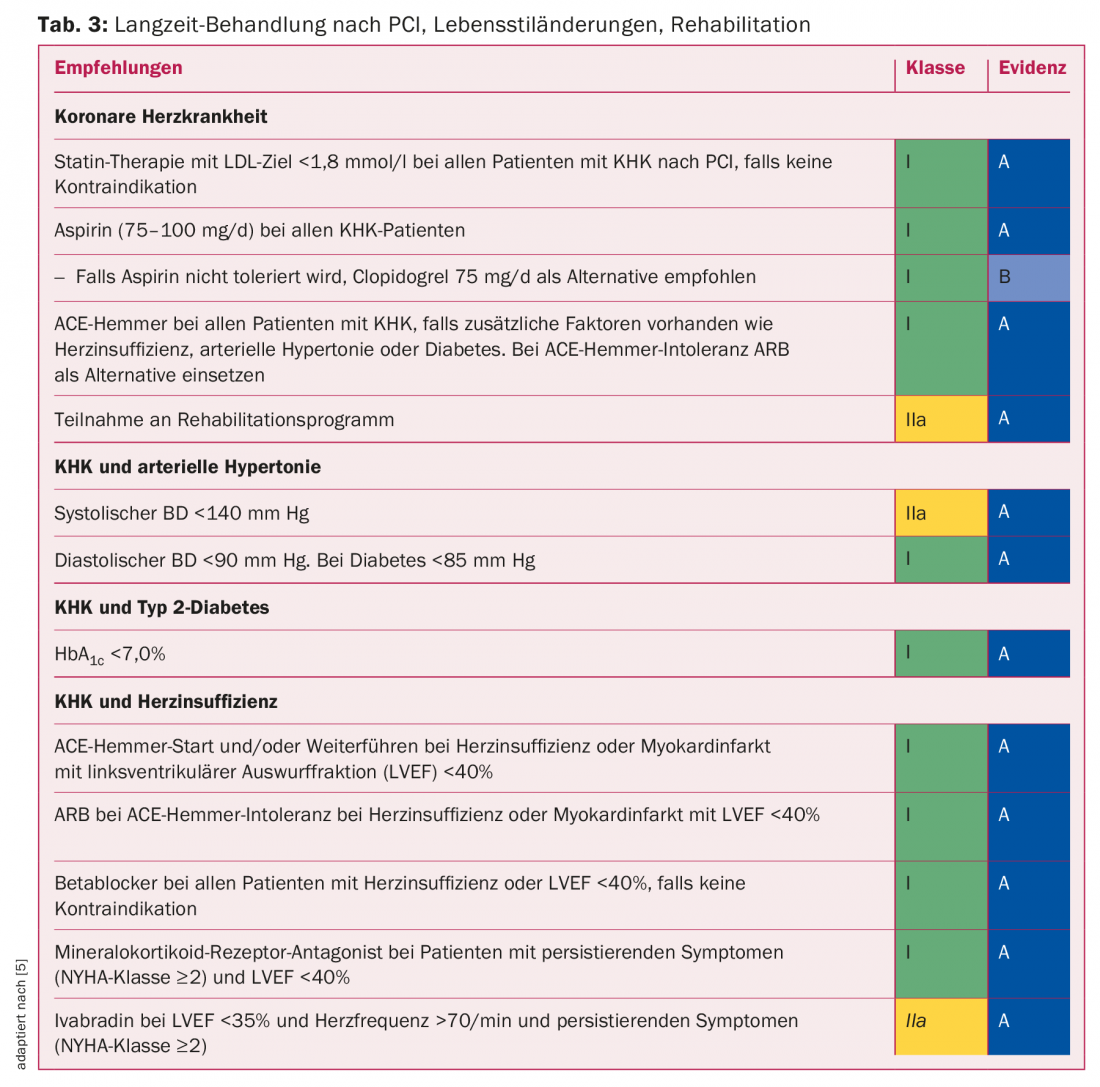

Importance of rehabilitation: Optimal secondary prevention is of central importance for a sustainable success of PCI. Initial PCI is known to solve only the acute mechanical problem; it does not cure the disease (CHD). Accordingly, control of cardiovascular risk factors is important for successful treatment. Target values for blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and blood glucose are shown in Table 3. After a catheter-based intervention, the course can be set anew for a sustainable lifestyle change.

Lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation, increased physical activity, weight control, diet, stress management, and others are even more difficult to implement compared to drug interventions. With outpatient or inpatient rehabilitation immediately following revascularization surgery, instruction and support are provided for the implementation of lifestyle changes and reintegration of the patient into his or her former environment. According to a recent meta-analysis, rehabilitation leads to approximately 20% fewer future cardiovascular-related hospitalizations. Even cardiovascular mortality can be favorably influenced, namely reduced by about a quarter [13]. Cardiac rehabilitation is cost-effective and is one of the mandatory services provided by the compulsory health insurance.

Recommended follow-up

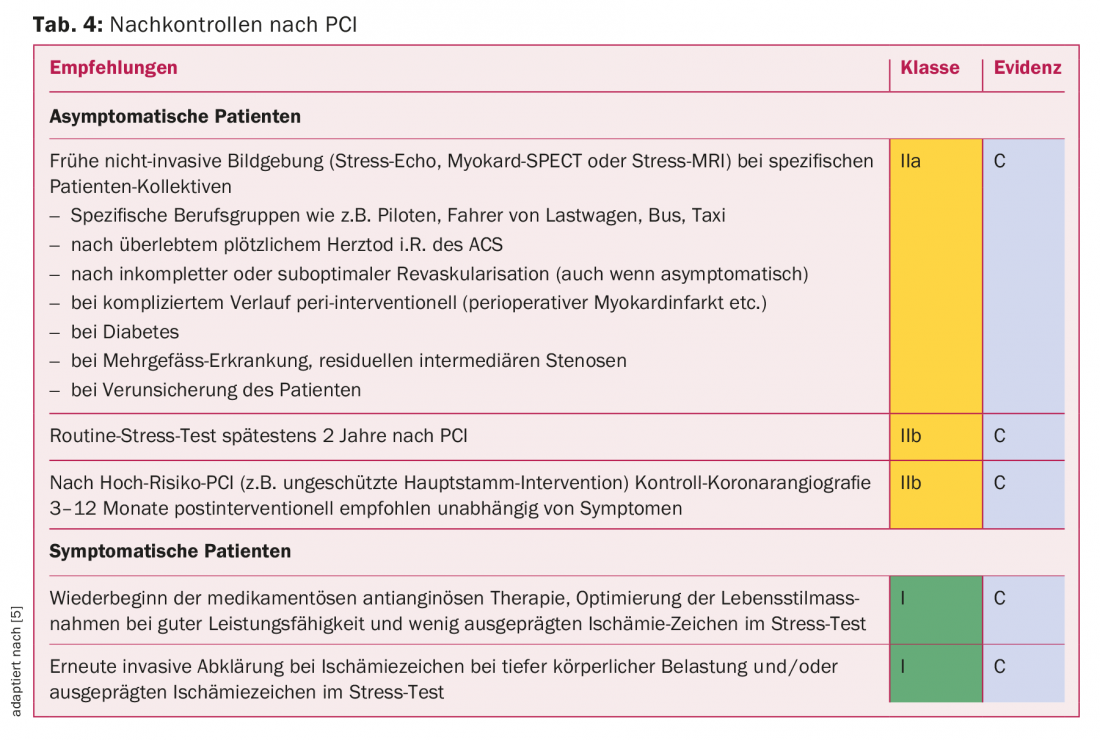

With regard to follow-up, recommendations exist, but they are not very evidence-based due to the lack of larger studies. Because of the improved performance of modern DES, ISR is relatively rare nowadays (<5% of cases) and re-ischemia is in the majority a reflection of progression of CHD. The focus during follow-up is not only on the recurrence of coronary ischemia but also on the individual optimization of the cardiovascular risk profile and the adjustment of antithrombotic therapy. The most important additional aspects are summarized in table 4.

Take-Home Messages

- With modern drug-eluting stents, the expected average stent thrombosis rate is now less than 1% and the instent restenosis rate is less than 5%.

- The type and duration of combined antithrombotic therapy vary relatively widely and depend primarily on the clinical setting (stable CHD vs. ACS), the need for additional anticoagulation (eg, atrial fibrillation), and the patient-specific bleeding risk.

- Sustained secondary prevention with the inclusion of a cardiac

- Rehabilitation is an integral part of management after revascularization, improving long-term prognosis and reducing the recurrence of ischemic symptoms.

- According to expert opinion, continuous medical monitoring of CHD patients after PCI is important to support the implementation of optimal secondary prevention and early detection of relevant instent restenosis or progression of CHD.

Literature:

- Gruentzig A: Transluminal dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis. Lancet 1978; 1(8058): 263.

- Stefanini GG, Holmes DR Jr: Drug-eluting coronary-artery stents. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(3): 254-265.

- Piepoli MF, et al: 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2315-2381.

- Byrne RA, Johner, Kastrati A: Stent thrombosis and restenosis: what have we learned and where are we going? The Andreas Gruentzig Lecture ESC 2014. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 2608-2620.

- Authors/Task Force members: 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 2541-2619.

- Wiviott SD, et al: Triton-TIMI 38 Investigators: prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. New Engl J Med 2007; 357: 2001-2015.

- Wallentin L, et al: PLATO Investigators. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1045-1057.

- Bhatt DL, et al: REACH Registry Investigators. Comparative determinants of 4-year cardiovascular event rates in stable outpatients at risk of or with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2010; 304(12): 1350-1357.

- Costa F, et al: Derivation and validation of the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score: a pooled analysis of individual-patient datasets from clinical trials. Lancet 2017; 389: 1025-1034.

- Van Diepen S, et al: Mortality and readmission of patients with heart failure, atrial fibrillation, or coronary artery disease undergoing noncardiac surgery: an analysis of 38,047 patients. Circulation 2011; 124(3): 289-296.

- Gibson CM, et al: Prevention of Bleeding in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing PCI. New Engl J Med 2016; 375(25): 2423-2434.

- Rickli H, et al: Stable angina pectoris: drug therapy vs. stent. The Informed Physician 2017; 2.

- Tada T, et al: Risk of stent thrombosis among bare-metal stents, first-generation drug-eluting stents, and second-generation drug-eluting stents: results from a registry of 18,334 patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013; 6: 1267-1274.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(3): 15-19