Community-acquired pneumonia is a heterogeneous clinical picture. The clinical diagnosis is not always clear. Many patients, especially older ones, lack typical signs such as cough, sputum, or fever. Demonstration of a pneumonic infiltrate on chest radiograph confirms the diagnosis. The severity and thus the need for hospitalization can be determined with simple parameters; comorbidities must also be taken into account. Patients treated as outpatients can generally be treated empirically without searching for causative pathogens; for patients treated as inpatients, pathogen diagnostics must be designed according to severity. If therapy fails, the primary consideration must be a complication or a differential diagnosis. Pulmonary infiltrates may also have a noninfectious cause.

Respiratory infections are common in family practice. Upper respiratory tract infections, acute bronchitis, exacerbated bronchiectasis, acute exacerbated COPD, and community-acquired pneumonia are not always easy to distinguish at first glance. However, only a delineation of these entities can ensure the therapy that, against the background of increasing antibiotic resistance and growing costs to the health care system, allows not only optimal patient care but also judicious use of antibiotics and efficient allocation of resources.

Community-acquired pneumonia – a heterogeneous disease

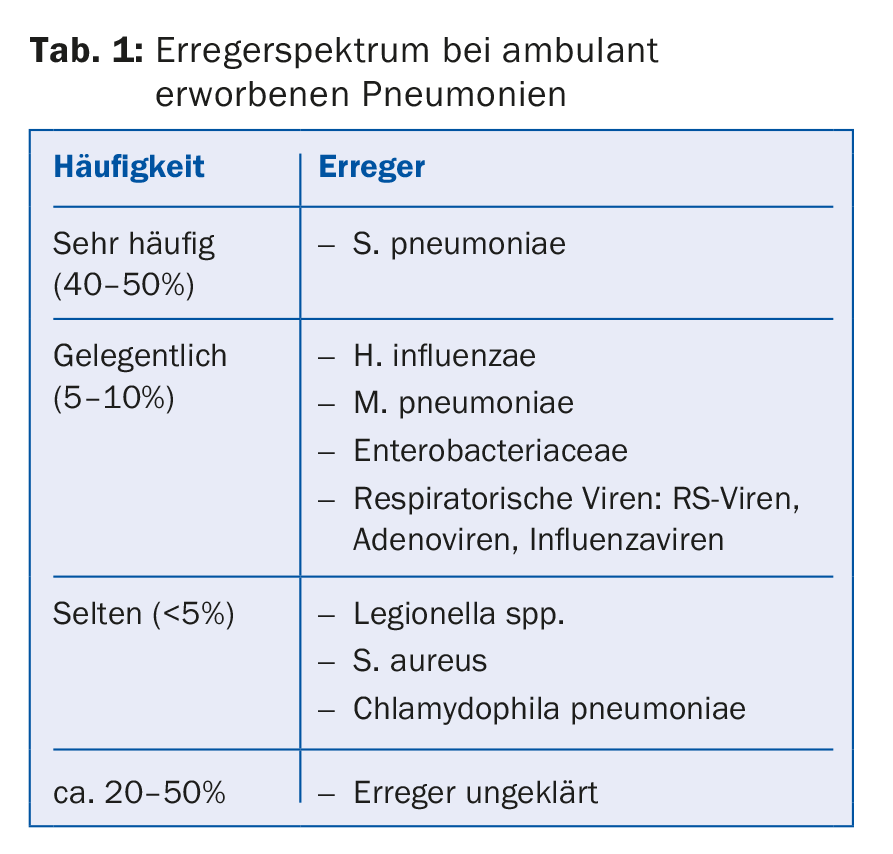

From a clinical point of view, it is useful to classify pneumonia – the microbially caused inflammation of the lung parenchyma – according to the site of acquisition and immune status of the patient. The major pathogens in outpatients who are not immunocompromised are summarized in Table 1. Pneumonia that occurs during a stay in a nursing or retirement home or during chronic hemodialysis treatment is also considered to be community-acquired.

The term “community-acquired pneumonia” encompasses a heterogeneous spectrum of clinical pictures, some of which are mild and without complications, but which can also represent life-threatening emergencies and have a relevant mortality (the mortality of all pneumonias treated in hospital is 10-20%). Pneumonia also frequently occurs in the terminal phase of pulmonary or extrapulmonary chronic disease (e.g., heart failure, malignancy, neurologic disease) or is at the end of life in the very elderly.

Clinic: not always specific

Pneumonia manifests itself on the one hand with respiratory symptoms (cough, purulent sputum, dyspnea) and on the other hand with systemic symptoms (feeling sick, fever or hypothermia, chills). It must be suspected if an immunocompetent patient has an acute illness with the leading symptom of cough without any other obvious cause, a new focal finding is apparent on clinical chest examination, and there is fever for more than 4 days, dyspnea, or tachypnea.

In elderly or chronically ill patients, the immune response decreases so that respiratory symptoms or fever may be mild or absent. Confusion, weakness, somnolence, decompensation of other diseases, or other nonspecific extrapulmonary symptoms may remain the only symptoms.

Chest X-ray remains gold standard

There are no symptoms specific to pneumonia. Also, the combination of history and clinical examination does not allow differentiation of pneumonia from another lower respiratory tract infection (acute bronchitis, acute exacerbation of COPD or bronchiectasis, influenza) with sufficient specificity to confirm the diagnosis and thus indicate antibiotic therapy.

Detection of pneumonic infiltrate by chest radiography is necessary to avoid overtreatment of lower respiratory tract infections with antibiotics. Furthermore, the radiograph allows to detect complications (lung abscess, empyema) and severity (multilobar infiltrates) of the pneumonia and gives indications of structural lung diseases (lung fibrosis or tumors).

Role of biomarkers

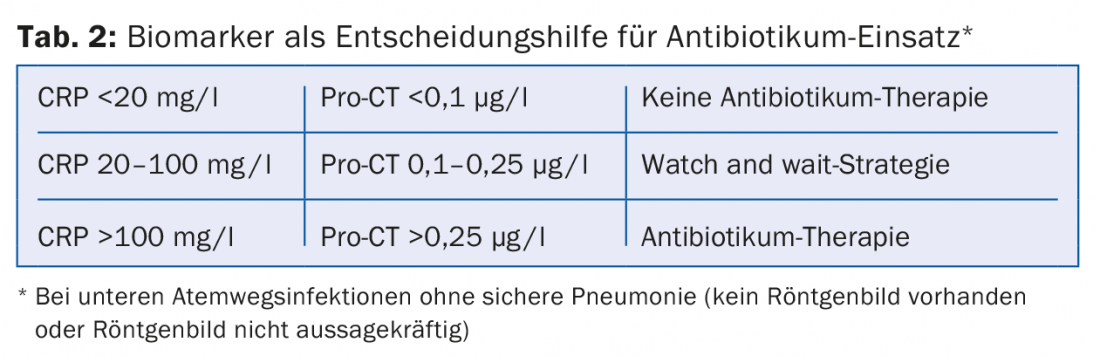

When pneumonia is diagnosed, it is always treated with an antibiotic. In unclear situations, e.g., when no definite infiltrate is recognizable or no radiograph is available, the therapeutic decision can be supported by biomarkers, but clinical assessment must always be paramount (Table 2).

Biomarkers such as procalcitonin (Pro-CT) and C-reactive protein (CRP), in addition to establishing the diagnosis, can be useful in assessing treatment response and determining the duration of therapy. Procalcitonin is sufficiently specific to distinguish bacterial from viral pneumonia, and intervention studies exist for procalcitonin to guide therapy. The main reasons for the nevertheless hesitant spread of procalcitonin measurement are the limited availability in the outpatient setting and the high costs.

Microbiological diagnostics

In general, the more severe the pneumonia, the more microbiological diagnostics are useful. Microbiological diagnostics are not recommended for outpatients, with the exception of immunosuppressed individuals. For more severely ill patients requiring hospitalization, it is carried out depending on the degree of severity. Blood and sputum cultures should always be obtained. However, sputum can only be cultivated meaningfully in the case of purulent sputum, good sputum quality and suitable logistics (processing within two to four hours).

The determination of the Legionella antigen in urine is sensitive and specific and – if positive – leads to a modification of the therapy. The recommendation for pneumococcal antigen testing is less strong because any empiric pneumonia therapy must be directed against pneumococci; however, positive detection can help detect pneumonia and focus antibiotic therapy.

If there is an intention to treat (severe pneumonia, symptoms <48 hours) and the epidemiological situation fits, detection of influenza by PCR should be sought.

Searches for Mycoplasma, Chlamydophila, Coxiella, or respiratory viruses are useful only in special situations, such as severe pneumonia (requiring intensive care), epidemics, or differential diagnostic considerations.

If invasive methods are available, bronchoscopic collection of tracheobronchial secretions or bronchoalveolar lavage should be discussed for severe pneumonia.

Parapneumonic pleural effusion

Concomitant pleural effusion occurs in 25-50% of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. From 10 mm extension it should be sonographed and diagnostically punctured. In addition to the macroscopic aspect, evidence of pathogens, or a pH <7.2, size (≥ half hemithorax) and evidence of loculation or septation are indications for drainage therapy (and possibly fibrinolysis) or thoracoscopic debridement.

Where to treat?

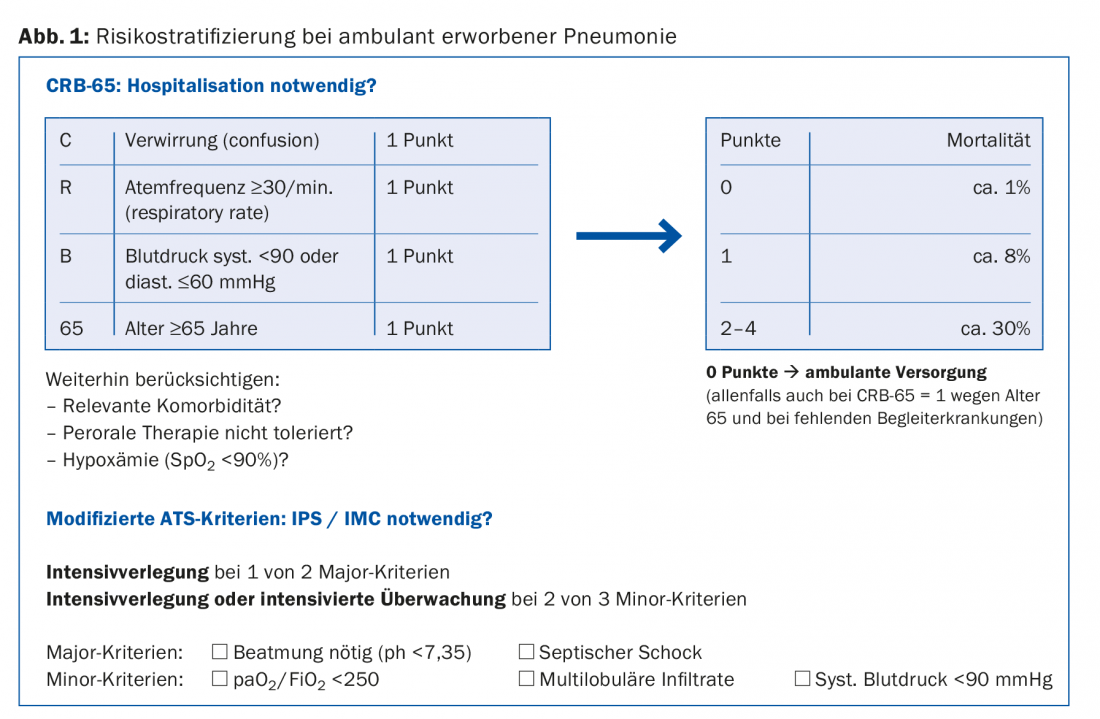

In patients who were in a functionally good condition before the disease, the prognosis and thus the need for hospitalization can be estimated by collecting simple parameters. The CRB-65 score, supplemented by a pulse oximetry survey of oxygenation, is well suited to determine the need for hospitalization (Fig. 1).

In patients with poorly controlled diabetes, severe renal or hepatic insufficiency, or severe cardiac disease, these conditions may decompensate rapidly and violently under pneumonia, so hospitalization is more likely in these cases. Social circumstances and opportunities for self-care may also necessitate hospitalization.

Antibiotic therapy

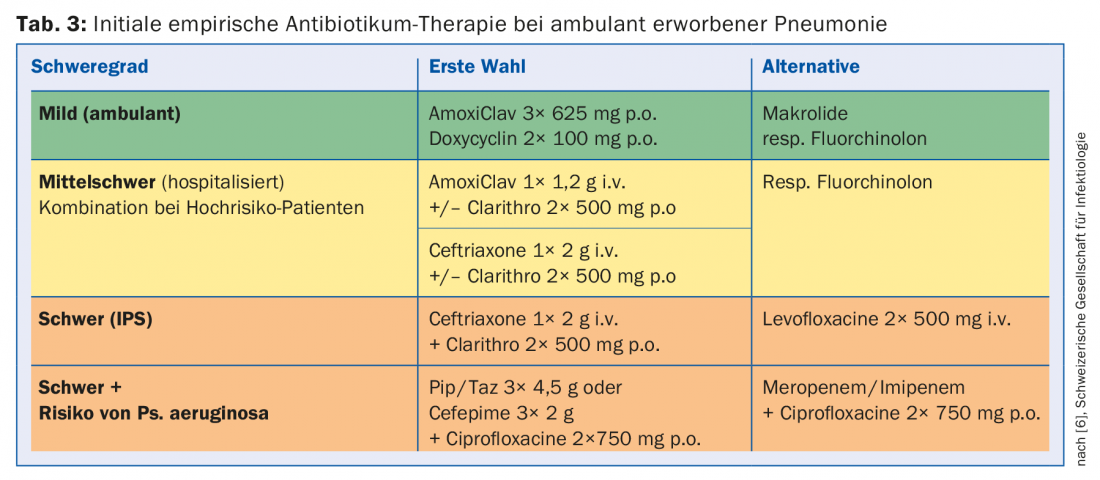

Even in cases where microbiological diagnostics are indicated, the pathogen usually cannot be detected promptly. Therefore, a calculated empirical therapy is performed based on the local pathogen and resistance situation as well as the risk factors for resistant germs. The recommendations for Switzerland are listed in Table 3 , although these may differ locally due to the pathogen and resistance situation. For moderate-to-severe pneumonia, initial combination therapy with a macrolide is still recommended until clinical stabilization. Its efficacy is not based solely on the additional coverage of atypical pathogens, but a favorable immunomodulatory effect is postulated, among other things.

The duration of therapy is usually five days for mild, uncomplicated pneumonias, five to seven days for moderate pneumonias, and up to ten days for severe pneumonias. A longer duration of therapy becomes necessary in cases of proven intracellular bacteria, lung abscesses, cavities, and empyema.

Systemic steroids?

The use of systemic steroids in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia is again coming into focus. It was shown in clinical studies that clinical stability was achieved earlier in hospitalized patients and that the duration of hospitalization and the use of parenteral antibiotics could be reduced, without any relevant disadvantages being observed in the short term. Which subgroups of pneumonia patients really benefit from systemic steroids, how the treatment should be carried out in detail, and whether the effect could not also be achieved by better attention to the clinic (stability criteria) and more prudent antibiotic use (“antibiotic stewardship”) has not yet been clarified, so that no recommendation can be made in this regard.

Other drugs

Dextromethorphan or codeine may be recommended for symptomatic treatment of an agonizing, nonproductive irritable cough. Expectorants, mucolytics, antihistamines, and bronchodilators are without proven evidence.

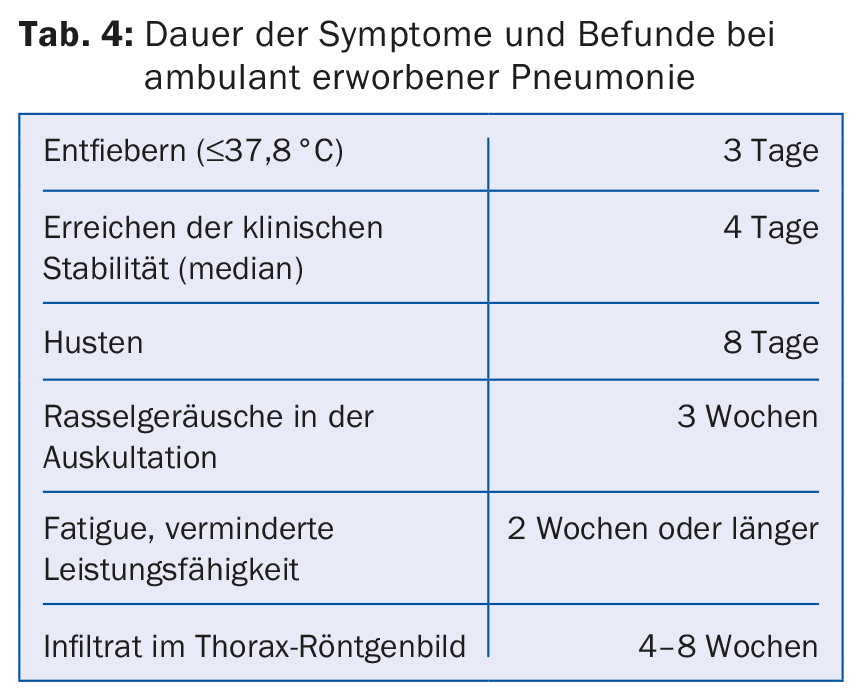

Endpoint of therapy: clinical stability

Symptoms of community-acquired pneumonia usually last much longer than until clinical stabilization (tab. 4). Therefore, it is not the definitive resolution of symptoms that should be considered, but clinical stability as a surrogate of response to therapy. The patient is designated clinically stable if the following criteria apply:

- No fever

- Normocardia and normotension

- No tachypnea

- No hypoxemia (SpO2 ≥90% or pO2 ≥60 mmHg below room air).

- Oral nutrition and medication possible

- Pre-existing mental status regained.

When clinical stability is achieved, the patient can be switched to peroral therapy if i.v. therapy was previously administered.

Early and late treatment failure

Early deterioration of the condition (<72 hours after the start of treatment = progressive pneumonia) is usually due to a failure to respond to initial therapy. Reasons include an uncovered pathogen, unexpected resistance, or a different diagnosis (pulmonary embolism, acute interstitial pneumopathy), but the main reason is the development of sepsis. Therefore, early treatment failure must be actively excluded even in outpatients by means of clinical monitoring 72 hours after initiation of therapy.

Two-stage deterioration occurring late after initial response to therapy (>72 hours) can usually be attributed to a complication of pneumonia (superinfection, abscess, empyema) or exacerbation of a comorbidity (heart failure, renal failure).

Non-resolving pneumonia, defined as the persistence of radiographic changes for more than four to eight weeks despite clinical response to therapy, should be distinguished from treatment failure. In these cases, an underlying lung disease must be sought, for example, bronchus carcinoma, bronchiectasis, organizing pneumonia, idiopathic interstitial pneumopathy, or vasculitis.

Aftercare

For community-acquired pneumonia treated in an outpatient setting, clinical monitoring is necessary on the second to third day after initiation of treatment to detect any early treatment failure. Even with a favorable course, the patient and family members must be instructed to report again if fever persists for more than four days, dyspnea increases, oral intake of food and fluids is not possible, impaired consciousness occurs, or any symptom persists for more than three weeks. There is little evidence for radiographic monitoring four to six weeks after pneumonia, but it is recommended in cases of persistent symptoms and higher risk for tumor disease (smoker, history of malignancy, age >50 years).

Primary and secondary prevention

Vaccinations against influenza and pneumococci are preventively effective. The new 13-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine included in the recommendations has the advantage over the previously used 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine of also being effective with respect to noninvasive infections and mortality and of maintaining its efficacy over time. Active smokers are recommended to stop smoking. In cases of suspected or obvious aspiration pneumonia, dysphagia should be recognized and treated in a timely manner. The indication for continuous medication that may promote pneumonia (inhaled corticosteroids, proton pump inhibitors) should be reviewed.

Literature:

- Prina E, et al: Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2015; 386(9998): 1097-1108.

- Musher D, et al: Community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(17): 1619-1628.

- Woodhead M, et al: Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J 2005; 26(6): 1138-1180.

- Ewig S, et al: S3 guideline. Treatment of adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia and prevention – Update 2016. Pneumology 2016; 70(3): 151-200.

- Eccles S, et al: Diagnosis and management of community and hospital acquired pneumonia in adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2014; 349: g6722.

- Laifer G, et al: Management of community acquired pneumonia (CAP) in adults (ERS/ESCMID guidelines adapted for Switzerland), www.sginf.ch/guidelines/guidelines-of-the-ssi.html (accessed Apr 25, 2016).

- Lim WS, et al: BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax 2009; 64 Suppl 3: iii1-55.

- Schuetz P, et al: Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 9: CD007498.

- Chalmers JD, et al: Severity assessment tools for predicting mortality in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2010; 65(10): 878-883.

- Wan YD, et al: Efficacy and Safety of Corticosteroids for Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 2016; 149(1): 209-219.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(7): 11-15