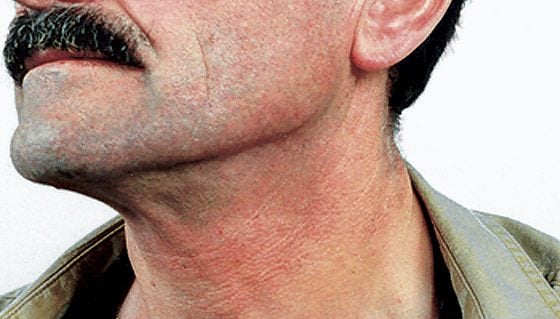

Many different types of cancer are associated with pain, which severely limits the quality of life of those affected. Still, the underlying mechanisms of this tumor pain are insufficiently understood. Although sensory nerves and blood vessels are close to each other in tumor tissue, neither interactions in this area nor the influence of angiogenic molecules on the pain process have been investigated so far. A recently published study now provides exciting insights into this field and suggests that growth factors from the VEGF family may also be responsible for tumor pain.

It is known that VEGF is expressed by various cancers to stimulate the growth of new blood vessels in the vicinity of the tumor. A group of researchers has now been able to show that neighboring nerve cells react sensitively to these messenger substances and thus appear to develop an oversensitization to pain stimuli.

VEGFR-1 upregulated in neurons

Specifically, the authors describe the nonvascular role of diverse VEGF family ligands in the development of pain. VEGF signaling appears to function not only in blood vessels but also in nerve cells. Through selective activation of VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR-1), tumor-derived VEGF-A, PLGF-2, and VEGF-B increase pain sensitivity. In mouse models, but also in human cancers, VEGFR-1 was shown to be upregulated in neurons, allowing increased “docking” of ligands. VEGF receptor 2 – highly relevant for tumor angiogenesis – does not seem to play a role in this context.

Conversely, the researchers found that local or systemic blockade of VEGF receptor 1 and its deletion or “switching off” prevented tumor-induced remodeling of nerve cells and thus also led to an attenuation of tumor pain – as shown by mouse models in vivo. The same effect was achieved by blocking VEGF family ligands.

The therapeutic potential of this discovery is great. According to these results, anti-angiogenic tumor therapies that directly target VEGFR-1 or also ligands from the VEGF family exert a palliative effect and possibly support the treatment of cancer pain. Studies that specifically examine tumor pain in the clinical endpoint are therefore useful with VEGF-targeting agents. The authors point to bevacizumab, a VEGF antibody that has been shown to improve quality of life in cancer patients. This finding would be consistent with the present study results, as pain relief is a major factor in increased quality of life. In fact, therapies that directly target VEGFR-1 instead of its ligands tend to be slightly more effective, according to the work.

The question remains open as to why only certain tumor types trigger pain and others do not, even though they have the same growth mechanisms. Furthermore, the authors emphasize that although their analysis revealed a strong link between VEGF signaling in sensory nerves, structural remodeling and pain, conclusive statements on causality cannot (yet) be drawn.

Source: Selvaraj D, et al: A Functional Role for VEGFR1 Expressed in Peripheral Sensory Neurons in Cancer Pain. Cancer Cell 2015; 27(6): 780-796.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(9-10): 4.