At an event during the SGIM congress in Basel, the topic was abdominal pain. PD Dr. med. Emanuel Burri, Kantonsspital Baselland Liestal, gave an overview of dyspepsia, discussed the current situation in the field of antibiotic resistance, and addressed the diagnosis of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. He also discussed possibilities of therapy for irritable bowel syndrome.

In principle, abdominal pain can be divided into acute and chronic or chronic recurrent forms. According to PD Dr. med. Emanuel Burri, Kantonsspital Baselland Liestal, one has to consider that in about half of all patients with chronic abdominal complaints a functional disease is suspected. Accordingly, no somatic cause is found. In the following, the speaker went into detail about various clinical pictures.

Dyspepsia

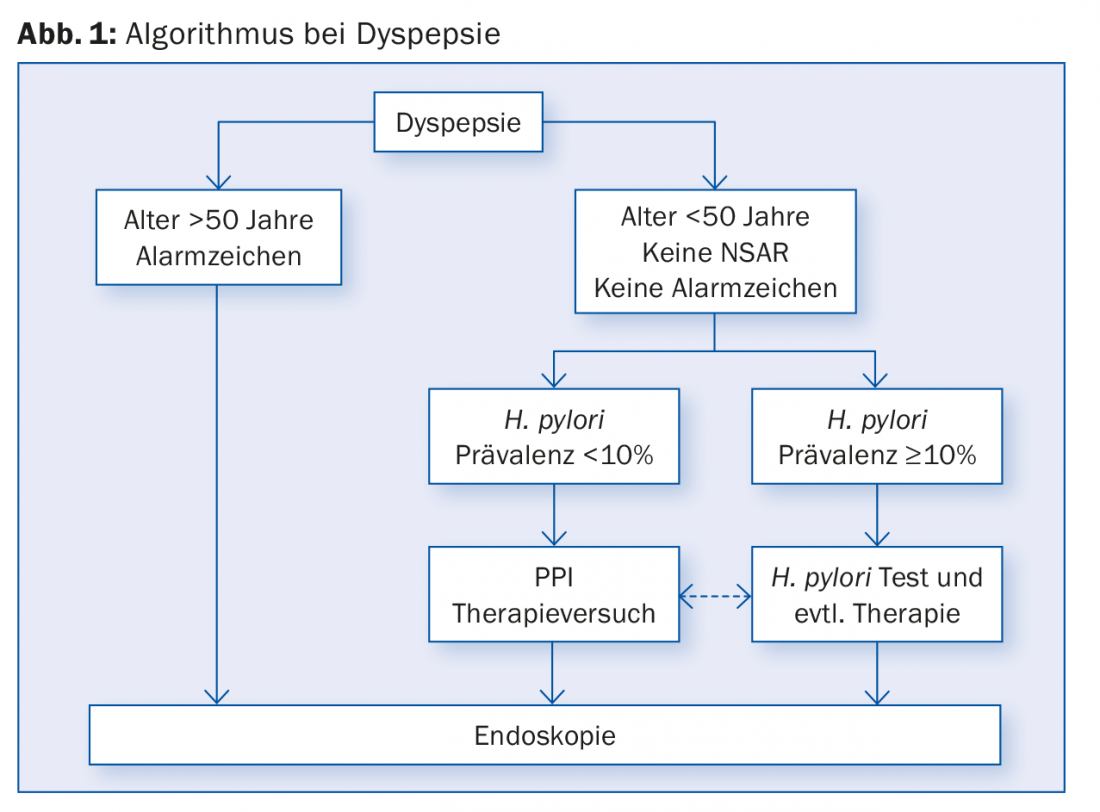

These are chronic or intermittent upper gastrointestinal tract complaints characterized by epigastric pain, loss of appetite, belching, bloating, heartburn, nausea, or vomiting. The prevalence is 20-40% of the normal population. Of these, 40% come forward. Thus, dyspepsia is a frequent reason for consultation in the family practice. “However, only a portion of symptomatic patients have a somatic condition,” Dr. Burri said. According to a meta-analysis of nine studies involving 5389 patients with unexplained dyspepsia, 73% of endoscopic findings were normal, 20% of those examined had reflux, 6% had an ulcer, and 1% had carcinoma. A possible clarification algorithm is shown in Figure 1 .

If the patient is over 50 years old and shows alarm signs, gastroscopy is necessary. Such alarm signs may include: positive family history (gastric carcinoma), involuntary weight loss, increasing dysphagia, odynophagia, gastrointestinal bleeding, iron deficiency anemia, persistent vomiting, and abdominal lymphadenopathy/ictal space.

If H. pylori prevalence is at least 10%, H. pylori testing and possibly therapy are indicated. Serology is not useful in this context, as it does not distinguish between active and passed infection. Better, but also expensive and time-consuming is the 13C breath test. It has a sensitivity and a specificity of 85-95%. Fecal antigen, which has identical sensitivity/specificity to the breath test, is feasible in practice. H. pylori testing should occur at least two weeks after discontinuation of PPI therapy and at least four weeks after stopping antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic resistance: How to proceed?

“A long-known and threatening problem is antibiotic resistance,” the speaker said. In Switzerland, the resistance rate to clarithromycin is about 20%, to metronidazole less than 30%, to levofloxacin 4-28%, which varies from region to region, and to amoxicillin/tetracycline 1-2%. With regard to bismuth, there is no resistance, but this is not standard in Switzerland. More common in first-line eradication therapy is the French regimen (clarithromycin 2× 500 mg/d + amoxicillin 2× 1000 mg/d + PPI 2x daily the standard dose). The Italian regimen, which uses metronidazole 2× 500 mg/d instead of amoxicillin, is used less frequently in Switzerland.

PPI therapy trial is effective

“For unexplained dyspepsia, PPI therapy is more effective than placebo (HR range of 0.77 to 0.54), according to a review [1] of four trials and 2164 patients. Overall, the risk of symptoms was reduced by 35% (HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.55-0.78). Treatment was more effective for heartburn than for epigastric pain.

“In the area of PPIs, there are also interesting new developments: Dexlansoprazole (Dexilant®), for example, is a PPI with a dual-release mechanism, which allows a longer duration of action and intake independent of food intake,” Dr. Burri explained.

Functional dyspepsia

In functional dyspepsia, eradication therapy has a small effect. Under PPI, symptom control is better than under placebo (relative risk reduction of 10.3%), but the Number Needed to Treat is relatively high, 14.6, according to a systematic review of seven studies involving 3725 patients [2].

“Phytotherapeutics should always be tried for functional dyspepsia,” the expert said. Multi-target therapy can be achieved with Iberogast® (motor activity, acid secretion, mucosal protection). A multicenter, double-blind, controlled study of 308 patients demonstrated the significant superiority of Iberogast® over placebo with respect to gastrointestinal symptoms from day 14 to day 56 [3].

Chronic inflammatory bowel disease

“40% of all patients with inflammatory bowel disease meet the Rome III criteria for irritable bowel syndrome,” Dr. Burri explained. A problem with all disease patterns is delayed diagnosis: 25% of patients with Crohn’s disease do not receive this diagnosis for more than 24 months. Just as many of the patients with ulcerative colitis wait more than a year before the condition is reliably diagnosed. “Calprotectin can be used to detect inflammatory bowel disease at an early stage,” Dr. Burri explained. “The single measurement from the stool sample is reliable. The test discriminates very well. Fecal calprotectin results in 67% fewer endoscopies, so it’s also an important value in terms of patient selection for rapid endoscopy.”

With regard to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), it should be noted that this is not a diagnosis of exclusion: According to the AGA Taskforce 2009, the probability of finding organic diseases in the absence of alarm symptoms is the same as in the normal population. The so-called FODMAP diet is an important part of IBS therapy. FODMAP is the abbreviation for Fermentable Oligo-, Di-and Monosaccharidesand(and) Polyols. The hypothesis that these dietary components should be avoided was published based on previous research on food intolerances to fructose, fructo-oligosaccharides, and lactose in Australia. According to studies, the procedure is very successful in reducing the symptoms of IBS – it reduces not only bloating, but also abdominal pain and intestinal wind. [4]. The diet should be planned in collaboration with a nutritionist.

“For drug therapy of constipation-type IBS (IBS-C), linaclotide (Constella®) is effective [5],” Dr. Burri said. It has been approved in this indication since March 2013. Linaclotide acts only locally in the intestine and is not absorbed. It does not make systemic side effects. The main side effect is diarrhea, leading to discontinuation of therapy in about 4% of patients.

Source: How to manage abdominal pain, SGIM Congress, May 20-22, 2015, Basel.

Literature:

- Talley NJ, et al: American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review on the Evaluation of Dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2005 Nov; 129(5): 1756-1780.

- Wang WH, et al: Effects of proton-pump inhibitors on functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007 Feb; 5(2): 178-185; quiz 140. epub 2006 Dec 14.

- von Arnim U, et al: STW 5, a phytopharmacon for patients with functional dyspepsia: results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Gastroenterol 2007 Jun; 102(6): 1268-1275.

- Halmos EP, et al: A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014 Jan; 146(1): 67-75.e5.

- Chey WD, et al: Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol 2012 Nov; 107(11): 1702-1712.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(7): 40-42