An educational event on February 12 at the Inselspital Bern focused on vertigo: Among other topics, the most important vertigo syndromes for the practice, video-oculography and current therapy options were discussed. Of great importance in diagnostics is the question of whether there is a central or peripheral cause. A concept with the catchy name “HINTS” helps here. In therapy, the options are varied depending on the type of vertigo and range from physiotherapeutic maneuvers to symptomatic treatments to surgical interventions.

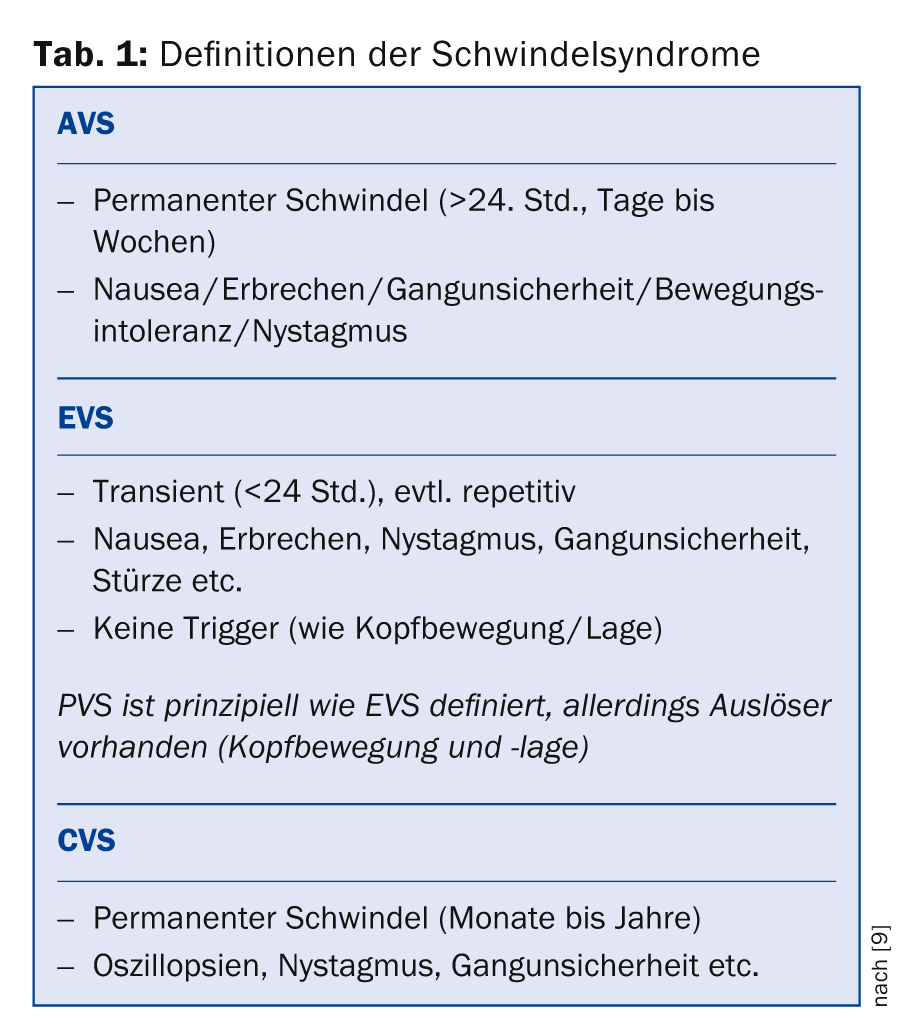

When can dizziness be dangerous? Georgios Mantokoudis, MD, University Department of ENT, Head and Neck Surgery, Inselspital Bern, Switzerland, addressed this question. “Dizziness is a common symptom in the emergency department: According to surveys, there are 2.6 million consultations/year in the U.S. and 250 000-500 000 emergency consultations for acute vestibular syndrome.” In this context, he reviewed the most important vertigo syndromes for practitioners. Vestibular syndrome is defined by spinning or swaying vertigo, nausea/vomiting, gait unsteadiness, motion intolerance, and spontaneous nystagmus. There are three main vestibular syndromes (depending on the temporal profile), defined by the international “Committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society” (Table 1):

- Acute vestibular syndrome (AVS)

- Episodic vestibular syndrome (EVS) with the subtype positional vestibular syndrome (PVS).

- Chronic vestibular syndrome (CVS) with the subtype “persistent postural-perceptual dizziness” (PPPD).

The most important differential diagnoses in AVS are neuritis vestibularis and cerebral apoplexy (especially posterior stromal area, brainstem and cerebellum). Pseudoneuritis also falls into this area. “About a quarter of all AVS patients have posterior stromal strokes,” Dr. Mantokoudis explained, adding that in PVS, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPLS) and orthostatic vertigo are the most prominent. EVS initially suggests Meniere’s disease and vestibular migraine or vertebrobasilar transient ischemic attack.

Central or peripheral?

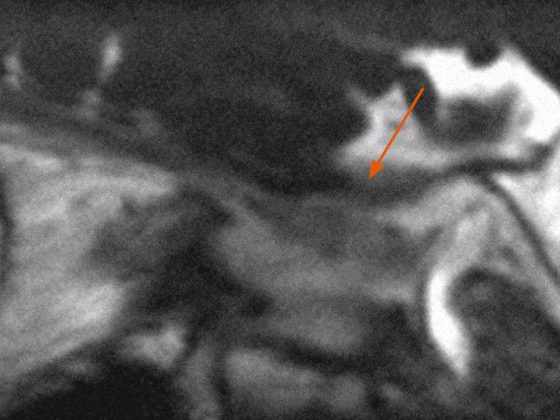

The most important question to ask in practice is whether there is a central or peripheral cause. “The diagnosis of vertigo is challenging,” the speaker emphasized, noting that 35% of strokes are missed during the initial consultation in the emergency department and 50% of patients with stroke and AVS have no focal neurologic symptoms or signs. CT demonstrates a high degree of accuracy in the early imaging of acute stroke (<24 h) has a sensitivity of about 16% and MRI (DWI) of 50-80%. The so-called HINTS examination is new, which can detect a cerebral stroke in AVS with a sensitivity of 98% and a specificity of 85% [1]. This involves a head impulse test (Head Impulse), a nystagmus test, and a test of skew (vertical divergence of the eyes). This is a quick, easy, and cost-effective way to determine whether the cause is cerebral or peripheral before imaging. A central cause of vertigo can be assumed if the head impulse test is normal, or if there is directional nystagmus, or if there is vertical divergence on the alternating cover test (it is sufficient if one of the three tests indicates a central cause). Thus, while the HINTS is a decision-making rule, the so-called ABCD2 score (Age, Blood Pressure, Clinical, Duration of Symptoms, Diabetes) is used more for risk stratification. A study [2] with emergency patients presenting with AVS had shown that the ABCD2 is not considered for stroke diagnosis because it only achieved a sensitivity of 61.1% and a specificity of 62.3% for a score of ≥4, which is significantly worse compared with the HINTS with 96.5 and 84.4%, respectively.

Thus, when is emergency imaging not necessarily indicated? According to the speaker, when all of the following are met:

- Subacute onset of vertigo (minutes to hours)

- No accompanying neurological symptoms (also no hearing impairment, headaches)

- No focal neurological findings

- Clinic consistent with unilateral peripheral-vestibular vertigo (HINTS: positive head impulse test, no skew deviation, no direction-changing nystagmus).

Video-oculography – future ECG of oto-neurologists?

Video-based techniques have recently become available for quantitative measurement of the patient’s vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR): So-called video-oculography is performed using fixed goggles (similar to swimming goggles), within which an accelerometer registers head rotation speed and an infrared camera registers eye movement. The data is analyzed by computer. The fixation point of the eyes can also be transferred to a camera on top of the glasses. The images from the head camera then show exactly where the patient is looking.

Video-oculography helps standardize the head impulse test – part of the HINTS. It is central that the glasses do not slip during jerky movements. Such motion artifacts, since they are not entirely avoidable, must be methodically compensated for. “A survey of 362 neurologists (DGN members) in 2014 had shown that still 96.2% of respondents perform the head impulse test (KIT) clinically – i.e., not quantitatively by means of video-oculography – although just one third trust their own assessment of the clinical KIT,” said Prof. Dr. Erich Schneider, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich.

In 2009, KIT could be reliably measured by video for the first time [3]. In the meantime, the technology has advanced further and has also been optimized for use in pediatrics, for example. Compared to the gold standard, the “scleral search coil”, video-oculography shows equally good results and is also mobile, much easier to use, and thus easier to integrate into the practice routine (suitable for the bedside and the emergency ward) [4]. The ratio between eye speed and head rotation speed calculated with this is called gain (eye speed divided by head rotation speed). If the gain is 1, it is a non-pathological result. If it is 0.5, it means that the eye compensates only 50% of the head movement. In the computer-based recording by means of velocity curves, even the smallest differences that are not visible to the naked eye, so-called covert saccades, can be easily reproduced.

With increasing age, the gain decreases more and more below 1. In a just submitted paper by Prof. Schneider and colleagues, a gain reduction of 0.012 per decade was shown. These standard values will be used to interpret oculography results in the future. Ultimately, the HINTS examination becomes much more accurate and easier with video-oculography. Within minutes, reliable quantification of the head impulse test is possible, which contributes to the rapid differential diagnosis of peripheral and central diseases. A proof-of-concept study on a small sample [5] was able to show a diagnostic accuracy of 100% for the video-based HINTS examination.

Therapy of vertigo

Prof. Dominique Vibert, MD, University Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Inselspital Bern, first reviewed the history of BPLS: It was first observed by Bárány in 1921. A good thirty years later, in 1952, Dix and Hallpike had described the provocative maneuver of BPLS, which is still used in diagnostics today. In 1969, Schuknecht was able to histopathologically demonstrate displaced otoliths on the cupula of the posterior arch, which led to the so-called cupulolithiasis hypothesis and the first description of the possible pathomechanism. Later, namely in 1992, Parnes and McClure described perioperatively free otoliths in the posterior arch canal-the canalolithiasis hypothesis was born, which is now considered a more precise explanation of the pathomechanism. 80-90% of BPLS cases are posterior arcuate, 10-20% lateral, and only 1-2% anterior. Physiotherapeutic maneuvers are commonly used: posteriorly the Brandt/Daroff, Semont, Epley, or the Gans maneuver; laterally geotropically the Barbecue or Gufoni maneuver; and laterally apogeotropically the modified Semont maneuver. In the very rare anterior form, Yacovino and colleagues described a new successful maneuver in 2009 [6]. Surgical procedures such as neurotomy of the singular nerve or occlusion of the posterior or lateral arcade are rarely performed.

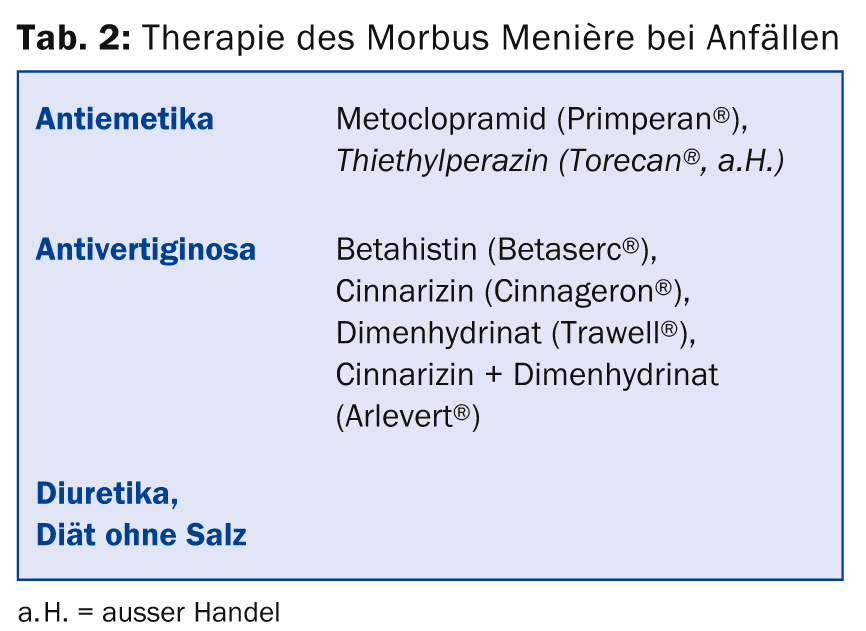

In acute vestibular deficit, treatment is initially symptomatic with antiemetics, e.g. metoclopramide (Primperan®) or formerly thiethylperazine (Torecan®, now off the market). Compared to vestibular physiotherapy exercises, corticosteroids achieve complete disease recovery earlier, but in the long term (after twelve months) the two procedures are equal [7]. Compared with placebo, significantly more patients on corticosteroids show caloric recovery at one month and at one year; cortisone therapy does not appear to play a role in clinical recovery [8].

Table 2 summarizes the drug treatment options for Meniere’s disease. The intratympanic injection of gentamicin and, since a few years, of cortisone have also been successful in basic and attack therapy. The latter form of therapy has the advantages that it is not ototoxic and does not cause systemic side effects. The treatment is performed locally on the diseased ear (under local anesthesia), but previous studies on this are very heterogeneous with respect to study protocols and therefore poorly comparable. The procedure for recurrent seizures and failure of drug therapy in the Bern ENT clinic includes insertion of a tympanic drain, intratympanic gentamicin therapy (both under local anesthesia), vestibular neurectomy (for functional hearing) or labyrinthectomy (for deafness).

Source: Interdisciplinary Symposium on Vertigo, February 12, 2015, Bern.

Literature:

- Kattah JC, et al: HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke 2009 Nov; 40(11): 3504-3510.

- Newman-Toker DE, et al: HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med 2013 Oct; 20(10): 986-996.

- Bartl K, et al: Head impulse testing using video-oculography. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009 May; 1164: 331-333.

- Agrawal Y, et al: Evaluation of quantitative head impulse testing using search coils versus video-oculography in older individuals. Otol Neurotol 2014 Feb; 35(2): 283-288.

- Newman-Toker DE, et al: Quantitative video-oculography to help diagnose stroke in acute vertigo and dizziness: toward an ECG for the eyes. Stroke 2013 Apr; 44(4): 1158-1161.

- Yacovino DA, Hain TC, Gualtieri F: New therapeutic maneuver for anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol 2009 Nov; 256(11): 1851-1855.

- Goudakos JK, et al: Corticosteroids and vestibular exercises in vestibular neuritis. Single-blind randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014 May; 140(5): 434-440.

- Goudakos JK, et al: Corticosteroids in the treatment of vestibular neuritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol 2010 Feb; 31(2): 183-189.

- Newman-Toker DE, et al: Vestibular Syndrome Definitions for the International Classification of Vestibular Disorders, ICVD. Barany Society Meeting, Buenos Aires 2014.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(3): 54-56