The goal of drug therapy for prostate cancer (PCa) is to prolong survival with acceptable side effects. Today, several drugs are available to achieve effective androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). The goal is to lower the testosterone level below 20 ng/dl. An indication for primary initiation of ADT exists in symptomatic metastatic PCa. An asymptomatic patient may also be offered ADT, but in this case a detailed weighing of possible advantages and disadvantages must be performed. If PSA progression occurs despite hormone manipulation, this is referred to as castration-resistant PCa. Treatment options in these patients include chemotherapy (primarily docetaxel), abiraterone, and enzalutamide.

Prostate carcinoma (PCa) is the most common form of cancer in Switzerland, with around 6000 new cases per year. With a median age of onset of 70 years, PCa is a disease of older men. The course is often progressive, depending on tumor stage and differentiation, but can often be favorably influenced by the use of drugs [1]. These are briefly summarized below.

Hormonal therapy of prostate carcinoma

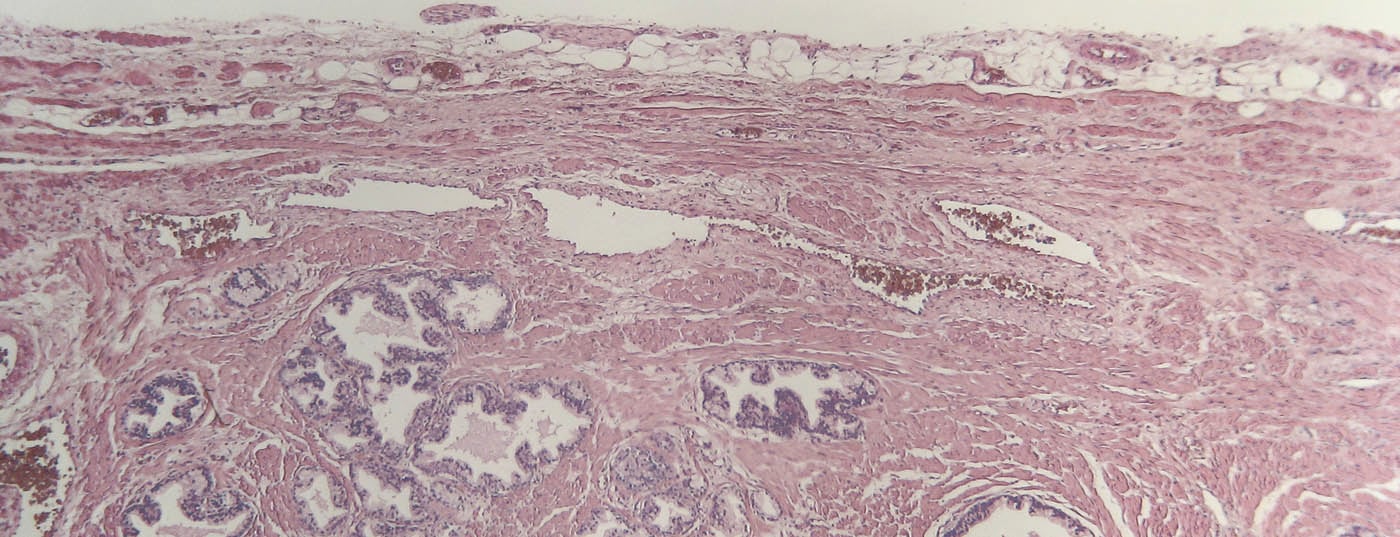

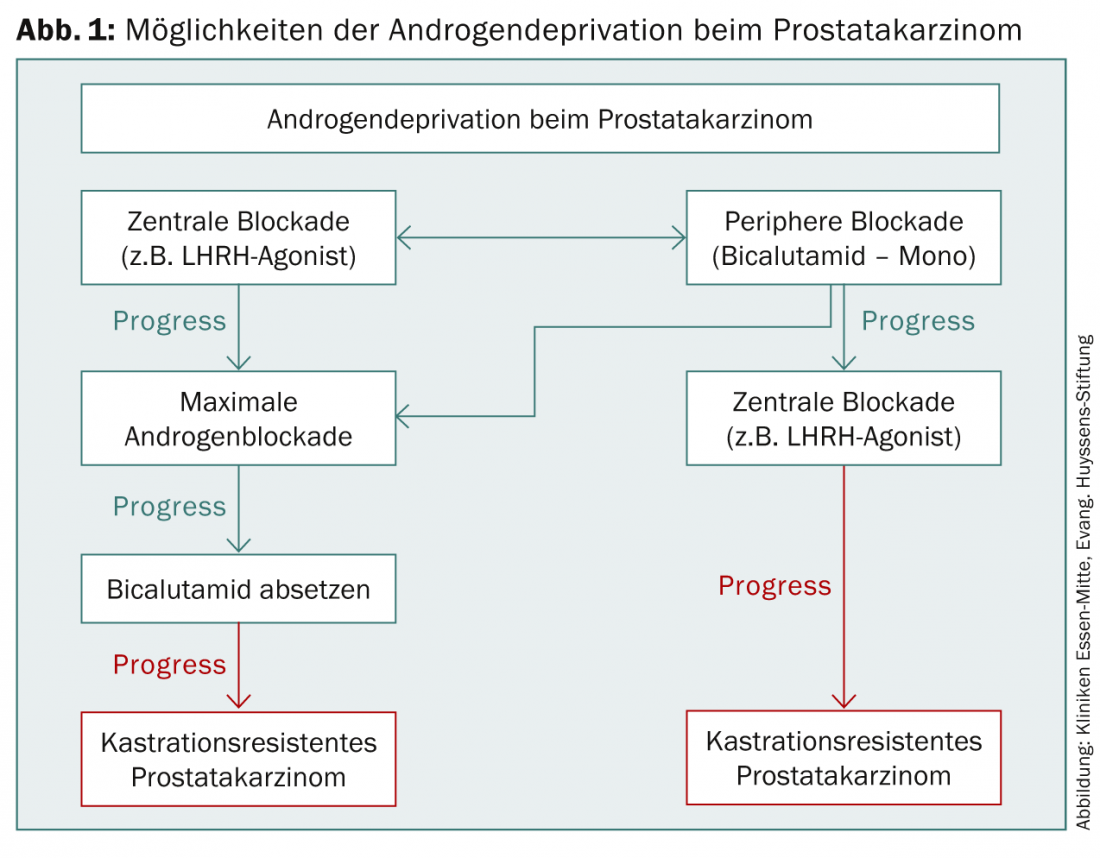

First and foremost in drug therapy for PCa is hormone therapy. In 1941, Huggins and Hodges first described the beneficial effect of androgen deprivation (ADT) by bilateral orchiectomy on prostate cancer, for which they were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1966 [2]. Today, various drugs are available to achieve effective ADT (Fig. 1). A reduction of the serum testosterone value below 50 ng/dl is indicated as effective [3]. However, more recent data show that surgical castration can even reduce testosterone to below 20 ng/dl – this value should therefore also be aimed for during castration with medication [4].

One of the indications for primary initiation of ADT is in symptomatic metastatic PCa. An asymptomatic patient may also be offered primary ADT, but in this case, detailed consideration must be given to potential adverse side effects, potential impact on quality of life, palliative nature of treatment, and prolongation of the progression-free interval. For tumor progression after previous therapy, ADT should be started if PSA doubling time is less than three months, symptomatic local progression, or distant metastasis is detected. ADT is also used periinterventionally in high-risk patients as part of percutaneous radiotherapy.Before brachytherapy, cryotherapy, or high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), ADT can reduce prostate volume [4].

LHRH agonists

Most commonly, an LHRH agonist is used for ADT [3]. This binds to the LHRH receptors and stops testosterone production by down-regulating the receptors in the pituitary gland. Initially, there is an increase in testosterone because the binding of the agonist to the receptor leads to increased production of LH and thus also testosterone. This must be intercepted by administration of an androgen receptor blocker such as bicalutamide 150 mg for two weeks before and two weeks after the initial administration of the LHRH agonist. The castration level is usually reached within this time [5,6]. LHRH agonists are injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly and are available as monthly deposits for 1-12 months, depending on the preparation. Common preparations include leuprorelin, goserelin and buserelin. Common side effects include hot flashes, loss of libido, and impotence, and with prolonged administration, osteoporosis and muscle wasting.

Intermittent androgen blockade as an alternative to minimize the side effects of ADT is currently not yet recommended as a routine treatment in the guidelines of the German Urological Society due to lack of long-term data on tumor-specific and overall survival. However, after prior education on the long-term data that are still lacking, intermittent ADT can be used to reduce the impact of medication on quality of life. The most common duration of therapy is 6-9 months followed by a break in therapy, which may vary depending on PSA dynamics [3,7].

During ADT, in addition to regular PSA determinations, testosterone levels should also be monitored regularly. If the level of castration is not achieved by the chosen agent, a change of agent, additional administration of an androgen receptor blocker (most commonly bicalutamide 50 mg) for complete androgen blockade, or subcapsular orchiectomy should be initiated [3].

LHRH antagonists

An alternative to the LHRH agonists are the LHRH antagonists Abarelix ( not approved in Switzerland) and Degarelix (Firmagon®). These LHRH receptor blockers do not cause testosterone to rise and lower testosterone below castration levels within just a few days, providing an alternative to castration in highly symptomatic metastatic PCa. There is a possibility of allergic reaction up to anaphylactic shock with the administration of Abarelix, this side effect is not observed with Degarelix [8,9].

Androgen Receptor Blocker

A variety of steroidal (e.g., cyproterone acetate) and nonsteroidal androgen receptor blockers are available that inhibit the action of dihydrotestosterone directly at the cellular level. The testosterone level is not lowered by this. For reasons of practicability, we will discuss here only the most common preparation with fewer side effects, the non-steroidal bicalutamide (Casodex® and generics).

Bicalutamide, taken orally, is approved for monotherapy in non-metastatic but locally advanced prostate cancer. It has been shown that similar survival times can be achieved by dosing 150 mg daily as by surgical castration [10]. Patients with metastatic PCa and a PSA >400 ng/ml showed shorter progression-free and shorter overall survival, but bicalutamide monotherapy can also be given to these patients – in view of the better quality of life compared with ADT – after appropriate education [11]. One of the most common side effects is gynecomastia, which is often painful, so prophylactic radiation of the mammary glands is recommended before starting therapy.

Maximum androgen blockade

If a PSA increase occurs with LHRH monotherapy, an androgen receptor blocker is added. This is called complete or maximal androgen blockade. It is also used when testosterone levels do not fall below castration levels with LHRH monotherapy, or when there is a PSA increase with bicalutamide monotherapy. However, the possibility of increased side effects must be discussed in detail with the patient. In an asymptomatic patient with PSA increase, it is also possible to wait initially while maintaining monotherapy and to initiate maximal androgen blockade only when symptoms appear [3].

Secondary hormone manipulation

If PSA rises again under maximal androgen blockade, discontinuation of the androgen receptor blocker may cause PSA to drop because of a developing point mutation in the testosterone receptor [12]. Furthermore, numerous other substances are available for secondary hormone manipulation, for example, corticosteroids, ketoconazole, aminoglutethimide, estrogens, progestagen, tamoxifen, somatostatin inhibitors, retinoids, and calcitriol. Ketoconazole, in particular, can prolong the time to initiate chemotherapy [13]. Before starting therapy, the patient should be informed in detail about the palliative nature of therapy, possible side effects, and the lack of evidence for prolonged survival [3].

Chemotherapy

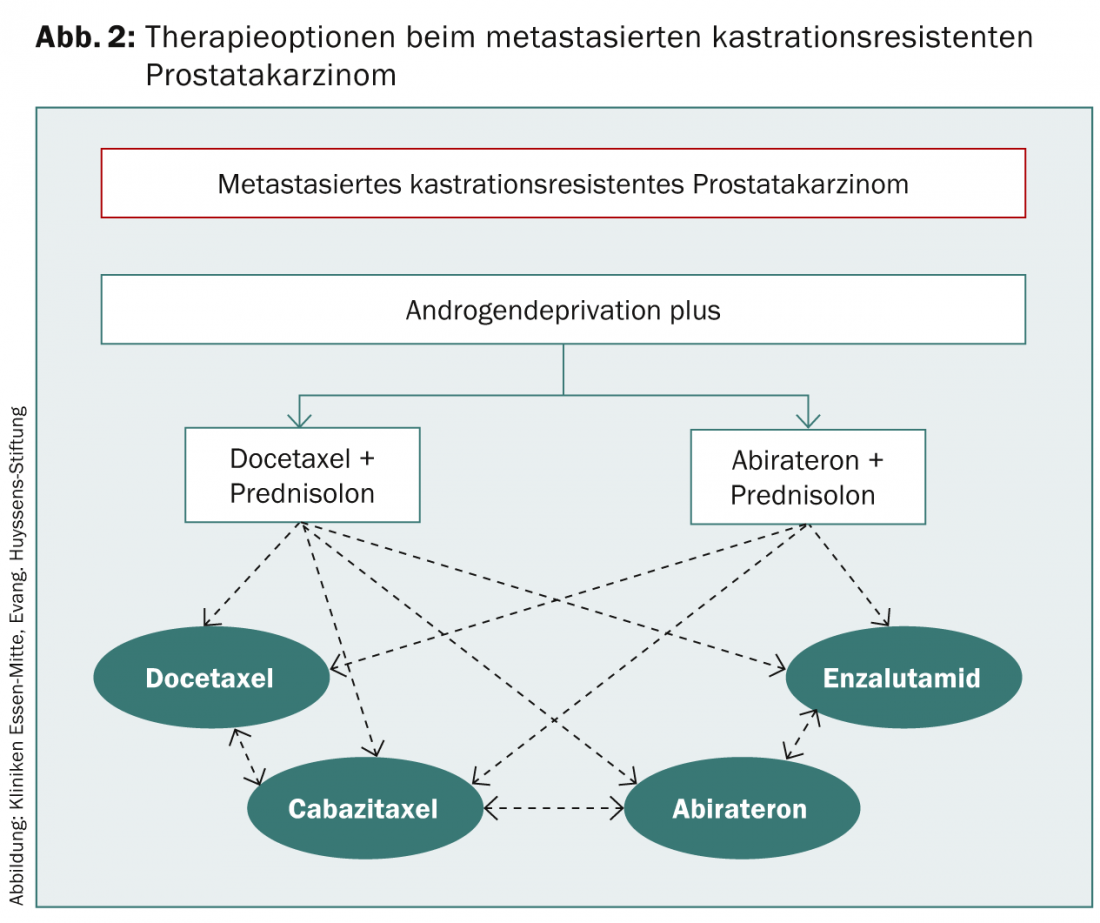

If PSA progression occurs despite secondary hormone manipulation, this is referred to as castration-resistant prostate cancer. In an asymptomatic patient, further waiting can be done. Indications for initiation of chemotherapy include progressive metastasis or rapid PSA doubling time and a PSA >15 ng/ml (Fig. 2).

Because of the side effects to be expected, careful consideration should be given in an asymptomatic patient as to when initiation of therapy is appropriate.

Docetaxel is used for first-line chemotherapy. Docetaxel 75 mg/m² is applied at three-week intervals along with 2× 5 mg prednisolone daily for 6-10 cycles. Pre-existing ADT should be maintained, but androgen receptor blockers must be discontinued at least four weeks before chemotherapy is started [3]. If disease progresses on docetaxel, a switch to cabazitaxel 25 mg/m² every three weeks in combination with prednisolone may be considered. In trials, a survival benefit occurred only after receiving at least three cycles of cabazitaxel. New data also show a survival advantage for docetaxel in first-line therapy before ADT, which will likely lead to a change in treatment sequence.

Abiraterone (Zytiga®)

Abiraterone (Zytiga®), a CYP17 inhibitor, lowers testosterone levels by inhibiting testosterone synthesis in the testes, prostate and adrenal glands. Since October 2011, abiraterone has been approved for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant PCa following tumor progression after docetaxel chemotherapy and is thus also recommended in the guidelines of the urological societies. Abiraterone is now also approved as first-line therapy for metastatic castration-resistant PCa, but only for asymptomatic to at most mildly symptomatic patients. It should be noted here that patients treated with abiraterone before docetaxel show more rapid disease progression after docetaxel administration than abiraterone-naive patients [14].

Abiraterone is taken in tablet form at a dosage of 1000 mg daily in combination with prednisolone; existing ADT is continued. Relevant side effects are mainly hypertension, hypokalemia and fluid retention due to mineralocorticoid excess.

Enzalutamide (Xtandi®)

Enzalutamide (Xtandi®) was approved in Europe in June 2013 for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant PCa following docetaxel therapy. The androgen receptor inhibitor is taken daily in tablet form with or without prednisolone. Relevant side effects are headache and hot flashes. There is a contraindication in case of severe hepatic dysfunction. In trials, oral administration of 160 mg enzalutamide daily resulted in significantly prolonged overall survival vs. placebo; therefore, enzalutamide is another alternative therapy to cabazitaxel and abiraterone [15]. Enzalutamide is also expected to be approved in fall 2014 prior to docetaxel chemotherapy.

Therapy of osseous metastases

For the treatment of osseous metastases, the guideline currently recommends the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid (Zometa® and generics) or the monoclonal antibody denosumab (Prolia®) [3]. In addition, radium-223 is also available when strictly indicated. However, a detailed discussion of these drugs would exceed the scope of this article, so reference is made to the topic-specific literature.

Conclusion

Currently, many different drugs are available for the treatment of advanced PCa. Especially in the field of metastatic castration-resistant PCa, the approval of numerous new drugs has resulted in promising therapeutic alternatives. However, further studies are urgently needed to develop evidence-based sequential therapy.

Take-home-messages

- The goal of drug therapy for PCa is to prolong survival with acceptable side effects.

- ADT should be continued even in the metastatic castration-resistant stage.

- Currently, an alternative to primary chemotherapy is abiraterone.

- Enzalutamide is another alternative after (and as of fall 2014, before) docetaxel therapy.

- There is not yet sufficient evidence to develop a stepwise schedule for drug selection in the metastatic castration-resistant stage.

- Effective drugs are available for the treatment of osseous metastases with zoledronic acid, denosumab and radium-223.

Literature:

- Cancer in Germany 2007/2008. 8th ed. Robert Koch Institute (ed.) and the Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registries in Germany (ed.). Berlin, 2012.

- Huggins C, et al: Studies on prostatic cancer. II. the effects of castration on advanced carcinoma of the prostate gland. Arch Surg 1941; 43: 209-223.

- Interdisciplinary guideline of S3 quality for early detection, diagnosis and therapy of the different stages of prostate cancer.

- Gomella LG: Effective testosterone suppression for prostate cancer: is there a best castration therapy? Rev Urol 2009; 11(2): 52-60.

- www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/043-022OLl_S3_Prostatakarzinom_2011.pdf. (Retrieved 11/08/2014)

- Auclair C, et al: Inhibition of testicular luteinizing hormone receptor level by treatment with a potent luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist of human chorionic gonadotropin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1977; 76(3): 855-862.

- Huhtaniemi I, et al: Response of circulating gonadotropin levels to GnRH agonist treatment in prostatic cancer. J Androl 1991; 12(1): 46-53.

- Tunn U: The current status of intermittent androgen deprivation (IAD) therapy for prostate cancer: putting IAD under the spotlight. BJU Int 2007; 99 Suppl 1: 19-22; discussion 23-24.

- Trachtenberg J, et al: A phase 3, multicenter open label, randomized study of abarelix versus leuprolide plus daily antiandrogen in men with prostate cancer. J Urol 2002; 167: 1670-1674.

- Van Poppel H, et al: Degarelix: a novel gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor blocker – results from a 1-yr, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 dose-finding study in the treatment of prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2008; 54(4): 805-813.

- Iversen P, et al: Casodex (bicalutamide) 150-mg monotherapy compared with castration in patients with previously untreated nonmetastatic prostate cancer: results from two multicenter randomized trials at a median follow-up of 4 years. Urology 1998; 51(3): 389-396.

- Kaisary AV, et al: Is there a role for antiandrogen monotherapy in patients with metastatic prostate cancer? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2001; 4(4): 196-203.

- Small EJ, et al: Second-line hormonal therapy for advanced prostate cancer: a shifting paradigm. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15(1): 382-388.

- Lam JS, et al: Secondary hormonal therapy for advanced prostate cancer. J Urol 2006; 175(1): 27-34.

- Schweizer MT, et al: The Influence of Prior Abiraterone Treatment on the Clinical Activity of Docetaxel in Men with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 2014; pii: S0302-2838(14)00069-4. doi:10.1016/ j.eururo. 2014.01.018.

- Scher H, et al: Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1187-1197.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2014; 2(8): 10-13.