Important advances are emerging in Alzheimer’s diagnostics. Soon, low-cost eye and smell tests could be included in early diagnosis. Several studies on this were presented at the AAIC Congress in Copenhagen. They promise a relatively simple and accurate initial assessment of the condition and could provide valuable indications for early therapy in routine screening in the future.

Shaun Frost, Perth, presented preliminary results from a small study of 40 participants that examined the extent to which amyloid-β, an important component in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, can be visualized in the retina. “Practical, low-cost screening that makes AD detectable and observable at an early stage, before irreversible brain atrophy occurs, could be a valuable key to early therapy in the future,” Frost said.

Researchers have found that amyloids have pathological effects not only in the brain, but also in the retina. For diagnostic imaging, the eye is naturally many times more accessible than the brain. Using curcumin, a natural dye, amyloid-β aggregates in the retina are now to be made fluorescently visible. To verify the results, Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET images were obtained in addition to the eye test in the study.

Two patient visits were required for the eye test. In between, sufferers had to take curcumin supplements (as a liquid). This dye binds with high affinity to amyloid-β and fluoresces in the retina. In addition, Frost says it is safe to use. The dye and images of the retina can be used to provide information on the amount, location, and distribution of amyloid plaques and to generate a retinal amyloid index (RAI). In the blood, curcumin uptake was monitored.

Results: Patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, patients with “mild cognitive impairment,” and healthy control subjects participated in the study. Preliminary results suggest that RAI correlates strongly and highly significantly (p<0.0001) with amyloid load in the brain (detected by PET scans). Thus, an eye test in early diagnostics seems to be profitable. The test was also able to distinguish between patients with Alzheimer’s disease and patients without Alzheimer’s disease with 100 percent sensitivity and 80.6 percent specificity. “The entire study, with 200 participants, will be completed soon,” Frost said. “Then we may know more precisely whether an eye test (possibly also as a regular check-up) is useful in addition to the existing diagnostic tools. It may then also be possible to use it to monitor progress in clinical studies.”

Further technologies in the pipeline

Other studies are also currently investigating the possibilities of a diagnostic eye test. Here, slightly different techniques are used to the one already mentioned. One of these studies was also presented at AAIC. Paul Hartung, Acton, presented the FLES system (“Fluorescent Ligand Eye Scanning”). Again, an amyloid-binding component (applied topically) is used to stain the plaques. They are then detected with a laser-based scanner. A recent study on the efficacy and safety of this procedure shows promising results.

Results: 40 subjects participated in the observer-blinded study. 20 were affected (mild to moderate probable AD) and 20 were healthy matched volunteers. The day before the measurement, the fluorescent ligand was applied as an ophthalmic ointment under the lower eyelid. The laser detected the ligand via a specific signature. In addition, PET scans were also performed here. There was a significant correlation between ocular and PET testing. In addition, it was possible to distinguish significantly between Alzheimer’s patients and healthy subjects – also with high specificity (95%) and sensitivity (85%). There were no serious side effects of the FLES diagnostic strategy. All 40 participants therefore terminated the study.

“At a cost of $300, such a test is about ten times cheaper than a PET scan. In addition, of course, it also has a much lower invasiveness,” says the expert. Such an eye scan takes only one millisecond and in about five minutes the computer outputs the result. Therefore, almost no training is required and the technique could be widely implemented and used by practice assistants or nurses. A Phase III study currently underway will provide further valuable information.

“I see great potential in this technology,” Hartung said. “One thing is certain, however: all of these advances can only really take effect when we finally have a better therapeutic strategy at hand to address Alzheimer’s even in its early stages and influence its course.”

Who has the right nose?

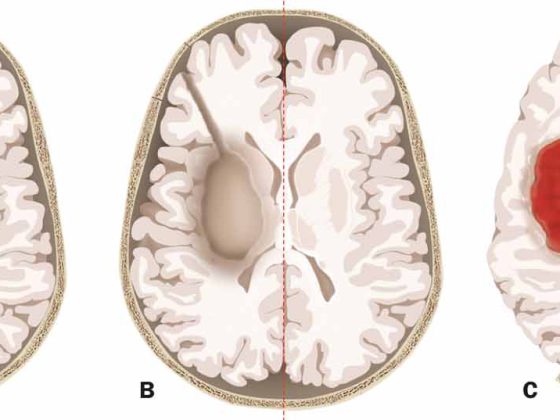

Olfactory sense could serve as another important biomarker. Deficits in this area show up early in Alzheimer’s disease. This is because the pathology of the disease affects not least the olfactory system in the brain (including the bulbus olfactorius and entorhinal cortex). Sometimes, therefore, olfactory tests such as the UPSIT (“University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test”) have been developed as potential screening tools. The UPSIT is very cost-effective and easy to perform in the clinic. Here, 40 fragrances are microencapsulated on paper. They can be released by scratching and identified by the patient in multiple-choice questions. A study now examined the relationship between olfaction, memory performance, biomarkers of neurodegeneration, and amyloid deposition in 215 clinically healthy elderly subjects. The UPSIT, neuropsychological tests, MRI and PET evaluations were used for this purpose.

Results: At this time, the results are all still considered preliminary and short-term, yet they are promising. In univariate analysis, poorer sense of smell was significantly associated with smaller hippocampal volume (p<0.001), reduced entorhinal cortex thickness (p=0.003), and marginally associated with PET evaluations (p=0.06). In multivariate models, thinner entorhinal cortex was significantly associated with poorer olfactory sense (p=0.03). Better smelling ability was again associated with better memory performance (p=0.03) – but this was only in the univariate, not in the multivariate analysis.

“The key finding from this study is that in clinically healthy elderly subjects with elevated cortical amyloid, more advanced neurodegeneration (thinner entorhinal cortex) was associated with poorer sense of smell,” concluded Matthew Growdon, MD, Boston. That is, there was indeed an association between the simple and inexpensive smell test and the expensive, laborious, and time-consuming PET and MRI procedures. This makes the olfactory test a potentially important diagnostic tool in the future that could indicate Alzheimer’s at an early stage or at least justify the use of subsequent invasive procedures such as PET. However, more long-term studies researching this are needed to make a firm statement on the efficacy of this procedure. “We ourselves plan to continue monitoring these patients for more than five years,” informed the expert.

Source: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2014, July 12-17, 2014, Copenhagen.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2014; 12(5): 42-43.