Itching massively affects quality of life and sleep and can thus lead to secondary problems such as lack of sleep, fatigue, depression, reduction of general condition and also cardiovascular problems. This article deals with old-age pruritus, which is usually very chronic and difficult to influence. Causes, investigation and treatment options will be discussed and the goal is to offer some starting points in diagnosis and treatment for the practicing physician and to make medical and nursing staff aware of this problem.

Already in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno the forgers, liars and alchemists are punished with an eternal itch. This punishment is deep in the eighth circle of hell, very close to the lowest point of hell and thus close to Lucifer. This clearly shows how even our ancestors judged itching as a severe punishment from God.

Itching is a very subjective symptom that cannot be measured objectively. Therefore, few randomized controlled clinical trials of pruritus therapy exist. Itching is defined as an unpleasant, diffuse sensation in the skin that results in scratching or triggers an imperative urge to scratch. Chronic pruritus is defined as itching that lasts longer than six weeks [1]. The mechanical irritation of the scratching process and also the damage to the skin trigger inflammatory responses, with cytokines (such as IL-31) and local neuropeptides and neurotransmitters in the skin playing an important role. A large part of the itching sensation finds its beginning in the skin and is then mostly transmitted via slowly conducting, unmyelinated C-fibers of the peripheral nervous system via the dorsal ganglia to the central nervous system, where the effectively perceptible itching then arises. Recent research [2] proves that already at the level of the peripheral nervous system, the transmission and pathways of itch are clearly separated from pain. However, pain and itching can directly affect each other. Usually the sensation of pain predominates, it can drown out the itching. Many patients with pruritus try to control the itch via pain triggers such as pinching or bloody scratching, as the pain is usually easier to bear than the itch. Scratching leads to inflammation and skin damage, which in turn makes the sensory system in the skin much more sensitive and damages the skin barrier, so that new irritations lead to increasingly severe itching attacks. The patient gets into a vicious circle that is very difficult to break. It is the physician’s task to identify the various causes and influences on itching and to control or alleviate it by appropriate systemic and topical measures.

Physiological causes of itching in old age

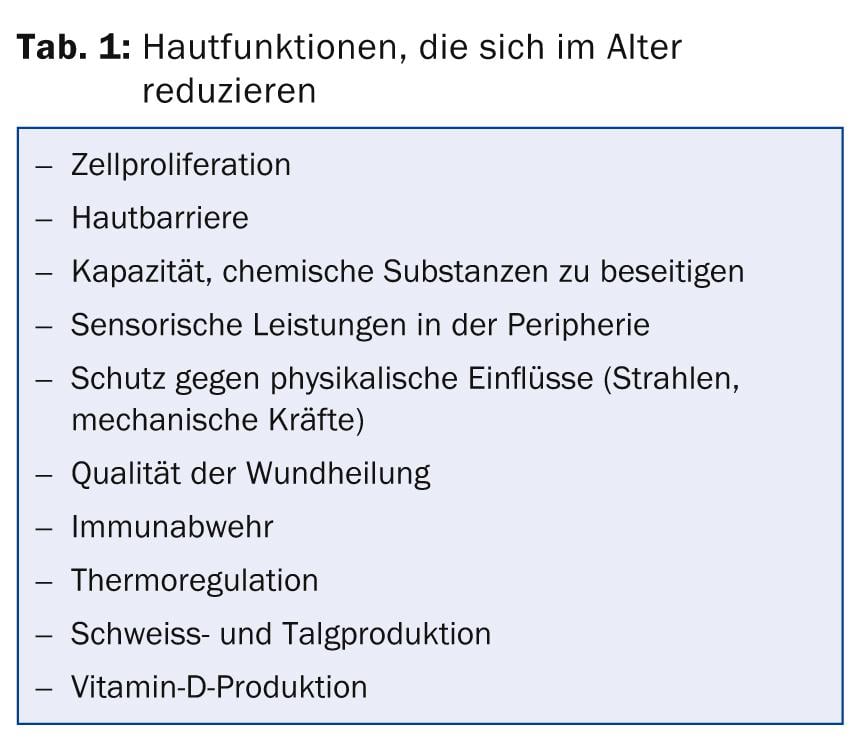

Itching is the main reason for dermatology consultations in patients over 65 years of age, and in addition to dry skin, age-related diseases such as diabetes mellitus, kidney or liver disease, thyroid disease, or medications play a role [3,4]. According to studies, more than 60% of people over 60 suffer from mild to severe itching every week [1]. Skin aging brings many changes, which in turn can affect itch (Table 1) [3,5,6].

The hormonal and functional reduction of sebum and sweat with age is one of the main reasons for dry skin. In addition, atrophy of the skin with a reduced cellular regenerative capacity and, above all, qualitative and quantitative changes in lipid production lead to dry skin and impaired barrier function. The skin barrier is critical in keeping potentially sensitizing or irritating substances such as fragrances, preservatives, detergents or other additives away from the living skin layer and the immune system. These chemical substances can trigger an allergic and/or irritant contact eczema, which can lead to itching via an inflammatory reaction or directly trigger sensory feelings such as tingling, formication, burning or itching via skin cells or skin nerve fibers. Finally, reduced resistance to mechanical forces (shear, tear or pressure) or to physical radiation lead to wounds or inflammation, which in turn trigger or intensify itching.

As early as the 19th century, the pioneers of dermatology, Hebra and Kaposi, postulated an age-related alteration of the peripheral nervous system with a subclinical neuropathy. Such neuropathy may initially lead to hypersensitivity with allodynia or cacodynia and later to hyposensitivity. This is exacerbated by additional diabetes. In any case, the emotional life in the skin changes with age.

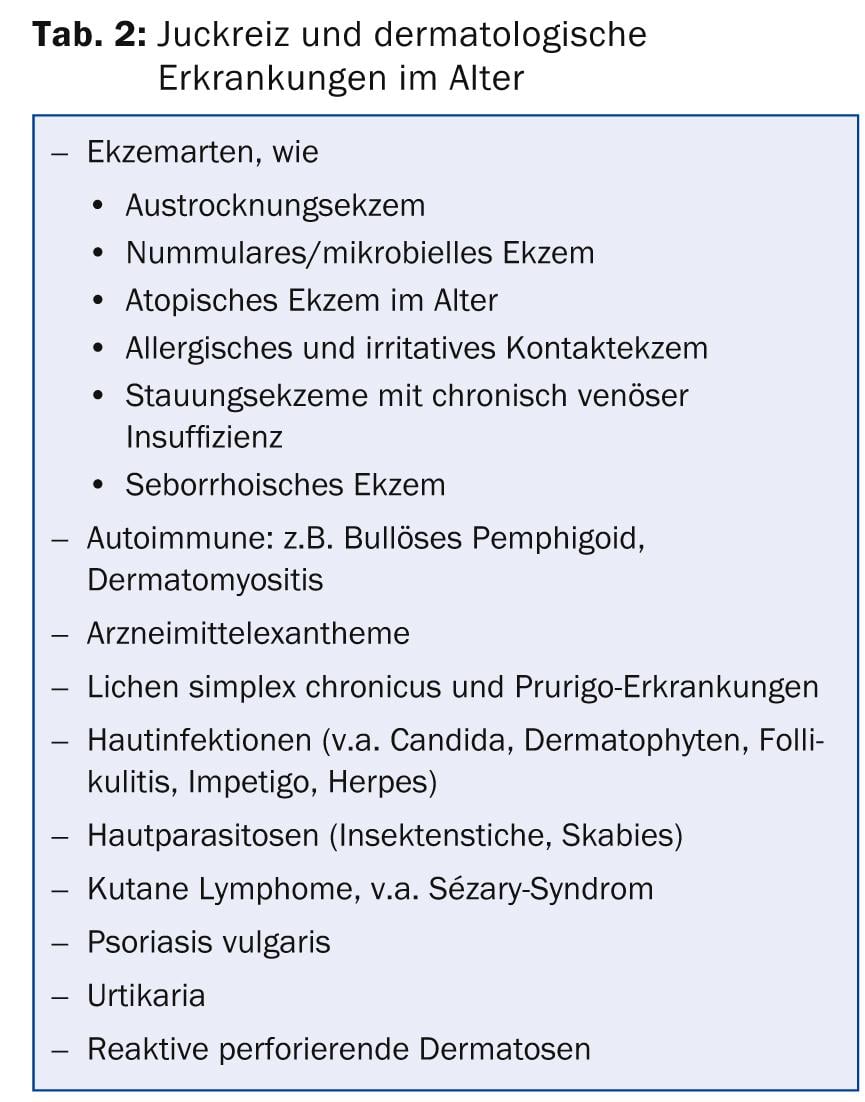

Dermatoses as triggers of itching

Table 2 summarizes the most important dermatologically relevant triggers of senile pruritus. The main cause of itching in old age is generally dry, cracked skin (xerosis cutis). This is certainly amplified in winter due to cold and dry air. Interestingly, my experience in the tropical environment in Singapore with high humidity (>80%) and temperatures always above 30 °C has shown that seniors under these conditions have the same amount of dry skin with itching as the comparison population in Switzerland. This means that humidity and temperature are less responsible for dry skin than genetic or age-related changes in the skin barrier.

One of the typical examples of damaged and altered skin barrier with dry skin is the mutation of filaggrin gene, which is associated with ichthyosis and atopic diseases in Caucasians [7].

Atopic predisposition is characterized by sensitive skin and mucous membranes in combination with allergies such as rhinoconjunctivitis or asthma and especially dry skin with atopic eczema. The dry, cracked skin combined with imbalance in the immune system leads to changes in the composition of the skin microbiome. Bacterial colonization of the skin is also greatly altered by the use of topical disinfectants, skin care products, and especially topical and systemic antibiotics. The composition of the microbiome of the skin, and probably also in the gastrointestinal tract, is becoming increasingly important in the genesis of different types of eczema and allergies. More studies are needed that examine genetic factors and the influence of the microbiome specifically in aging skin.

Dry skin can lead to very inflammatory and itchy desiccation eczema due to constant scratching, bacterial and mycological colonization and skin irritation. The treatment of chronically dry and itchy skin tempts patients to use all sorts of home remedies, which in turn, however, can trigger skin irritations and allergies again. Sometimes alcohol-containing products are used, as they provide short-term itch relief by cooling, or regular cold or hot showers are taken. All these measures irritate, degrease and dry out the skin even more and are therefore counterproductive.

A special form of desiccation eczema is the circular, well-limited subacute eczematous lesions of nummular-microbial eczema. At the same time, this type of eczema also appears to be a variant of atopic eczema in the elderly.

Of particular importance in old age is stasis dermatitis in chronic venous insufficiency and chronic edema of the legs. The lymphedema, trophic circulatory disorders of the skin and also the stasis purpura lead to inflammation, itching and eczematous lesions. It is then also important to treat the cause, namely the edema in the legs, with consistent compression therapy (support stockings or short-stretch bandages). In recurrent stasis eczema that does not respond even to correct therapeutic approaches, additional allergic contact dermatitis must be ruled out. The clarification of allergic contact dermatitis is based on a good history, accompanied by epicutaneous tests with correct evaluation.

Itching can sometimes be the first symptom of bullous pemphigoid, and the typical tense blisters appear later. Sometimes bullous pemphigoid may appear under the clinic of crusted erosions similar to seropapules in purigo simplex subacuta. Specific single-cell lesions and, above all, histopathology and immunofluorescence with the typical band-shaped deposits of IgG and complement in the area of the basement membrane lead to the correct diagnosis.

Epidemics of itching with nocturnal symptoms in nursing homes are very typical of infections of the skin with Sarcoptes scabiei (scabies). Prompt and correct diagnosis and treatment of all contacts is critical to the management of scabies. The antiparasitic drug ivermectin is increasingly prescribed for the treatment of this skin parasitosis. However, the persons in contact must also be treated and the parasites in clothes and bedding must be eliminated.

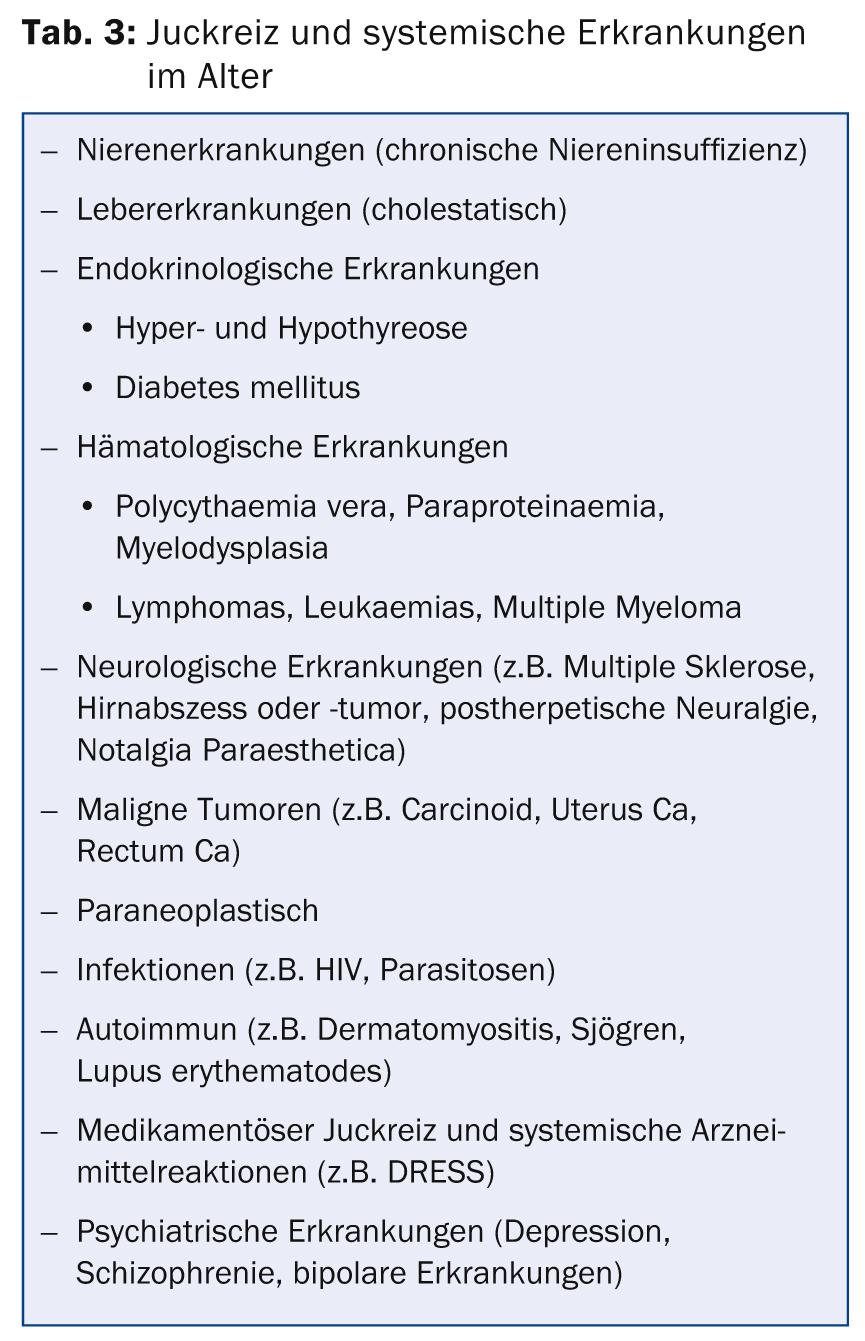

Systemic diseases as triggers of itching

Various systemic diseases, which become more frequent in old age, are responsible for itching in old age (Tab. 3). Diabetes mellitus plays a special role. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy is pathogenetically implicated and may lead to chronic pruritus. This itching may be an early symptom of diabetes mellitus. Therefore, a more in-depth evaluation of itching can often reveal hidden diabetes mellitus and thus initiate early and correct treatment and diet.

Severe and refractory localized and generalized pruritus is often present in chronic renal failure, and sometimes dialysis can only partially help. Cholestatic pruritus is the main cause of chronic itching in liver disease. Liver diseases without cholestasis, such as viral hepatitis or cirrhosis, are usually not associated with itching. An important differential diagnosis for chronic pruritus in the elderly is malignant disease. Pruritus is an important paraneoplastic symptom especially in hematologic malignancies and myelodysplasias; these must always be excluded. Sometimes carcinomas of the rectum, uterus, or prostate can cause localized itching symptoms in the genito-anal area.

Drugs per se can cause itching without specific sensitization and without skin manifestation. Numerous drugs commonly used in geriatrics can trigger such pruritus, such as opioids, hydrochlorothiazide, estrogens, ACE inhibitors, allopurinol, simvastatin, amiodarone, and many others (see also Jerome Y. Litt, Drug Eruption Reference Manual, Parthenon Publishing Group). Often these are non-allergic reactions with nonspecific, pharmacological release of biogenic amines. However, most systemic drug reactions manifest with sometimes characteristic skin manifestations (maculopapular, pustular, eczematous, vesicular). Sometimes peripheral eosinophilia may occur in isolation without skin manifestation and may indicate an allergic drug reaction. Fever, lymphadenopathy, elevation of transaminases, or pharyngitis may also indicate a DRESS (“Drug Related Eosinophilia with Systemic Symptoms”) syndrome. Since a wide variety of medications are prescribed in old age and itching can sometimes take several weeks or months to appear, clarification of drug-induced itching is not always easy and sometimes all medications must be discontinued or replaced for at least a month. The anamnesis is the most important tool for a correct diagnosis. Necessary medications can then be reintroduced one at a time with one- to two-week intervals. If skin symptoms are present, allergological clarification with skin tests may be useful.

Clarifications of the age pruritus

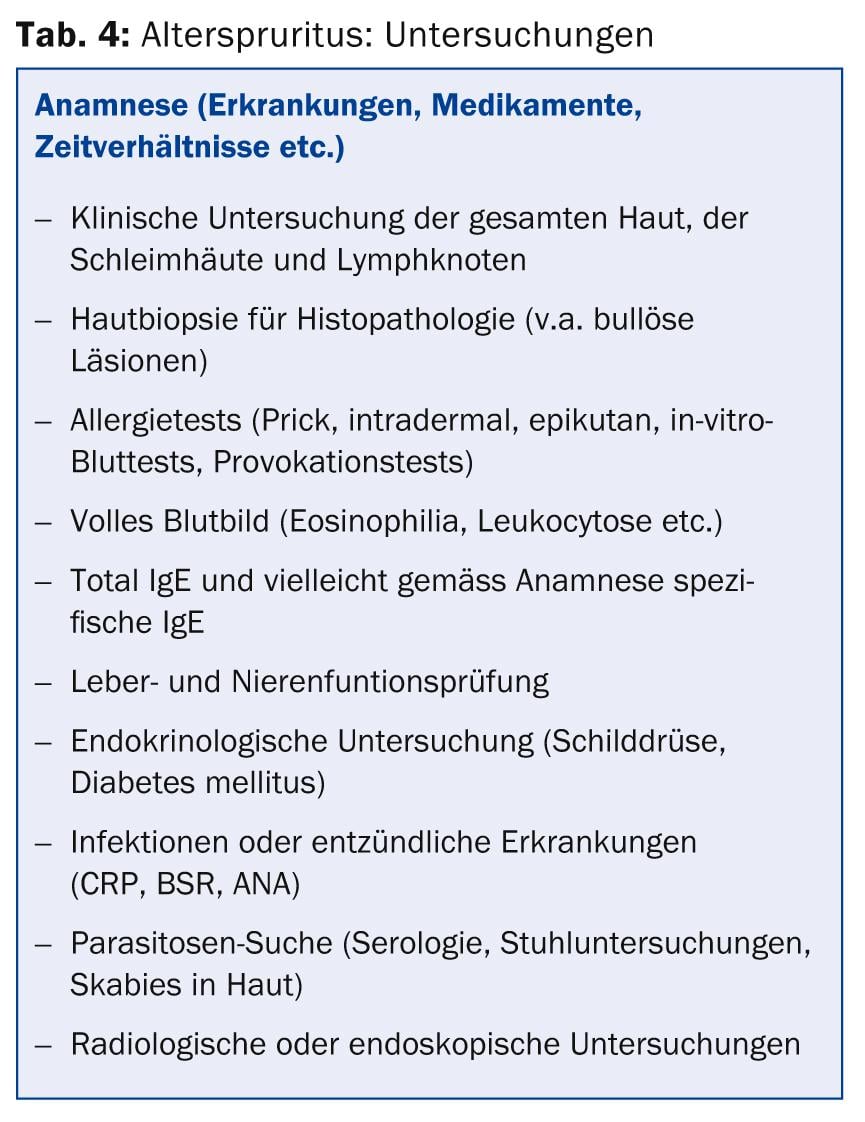

As with all pruritus, the exact anamnesis is decisive for a correct clarification of old-age pruritus. Above all, the time ratios are decisive. Since when has the pruritus existed, did it occur abruptly from one day to the next or insidiously over days and weeks, is it bound to certain times of the day or to a monthly periodicity, are there certain triggers or temporal correlations with food intake, medication use or application of external products? In addition, it is essential to take a very accurate history of diseases and operations. Decisive is also information about the social environment and the family, whether the itching has occurred in isolation or whether other people in the close environment are also affected. Family and personal history may provide evidence of atopic predisposition (allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, bronchial asthma, atopic eczema).

The correct history already accounts for more than half of the itch history, and the following investigations confirm the suspicion or may lead to a new lead, which must then be confirmed by an extended history. Table 4 summarizes the further investigations in pruritus, where a detailed examination of the whole patient (including mucous membranes) is crucial. The additional examinations mentioned depend on the clinical picture and the medical history.

Therapy of senile pruritus

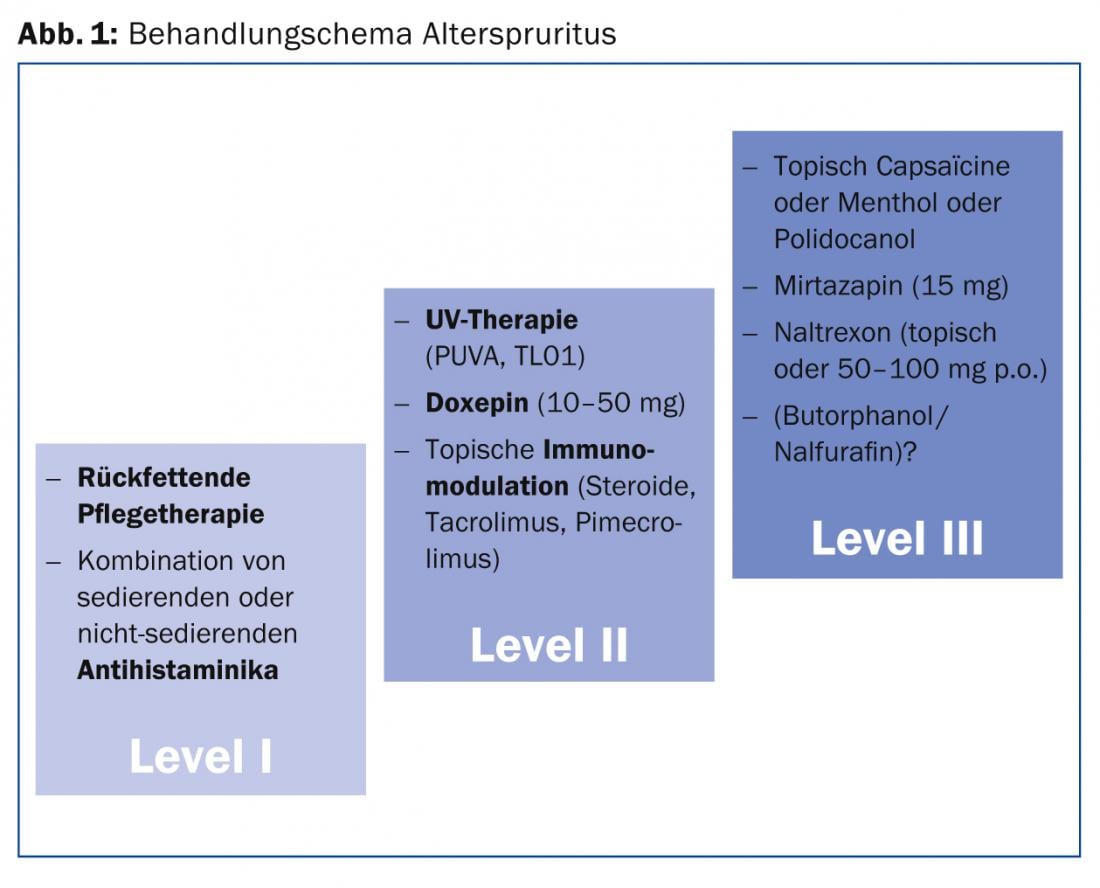

Figure 1 shows a possible therapy scheme.

Especially in old-age pruritus, it is important that therapy focuses on the multiple identified causes and aggravating additional factors. Each individual issue must be addressed in a multidisciplinary approach and corrected or treated as best as possible. Possible irritant or allergic causes must be identified and avoided. In particular, a detailed medication history can indicate possible drug-related causes of pruritus. Then this suspicious therapy must be replaced or discontinued for at least one month. If there is no improvement in pruritus, the drug was probably not the cause.

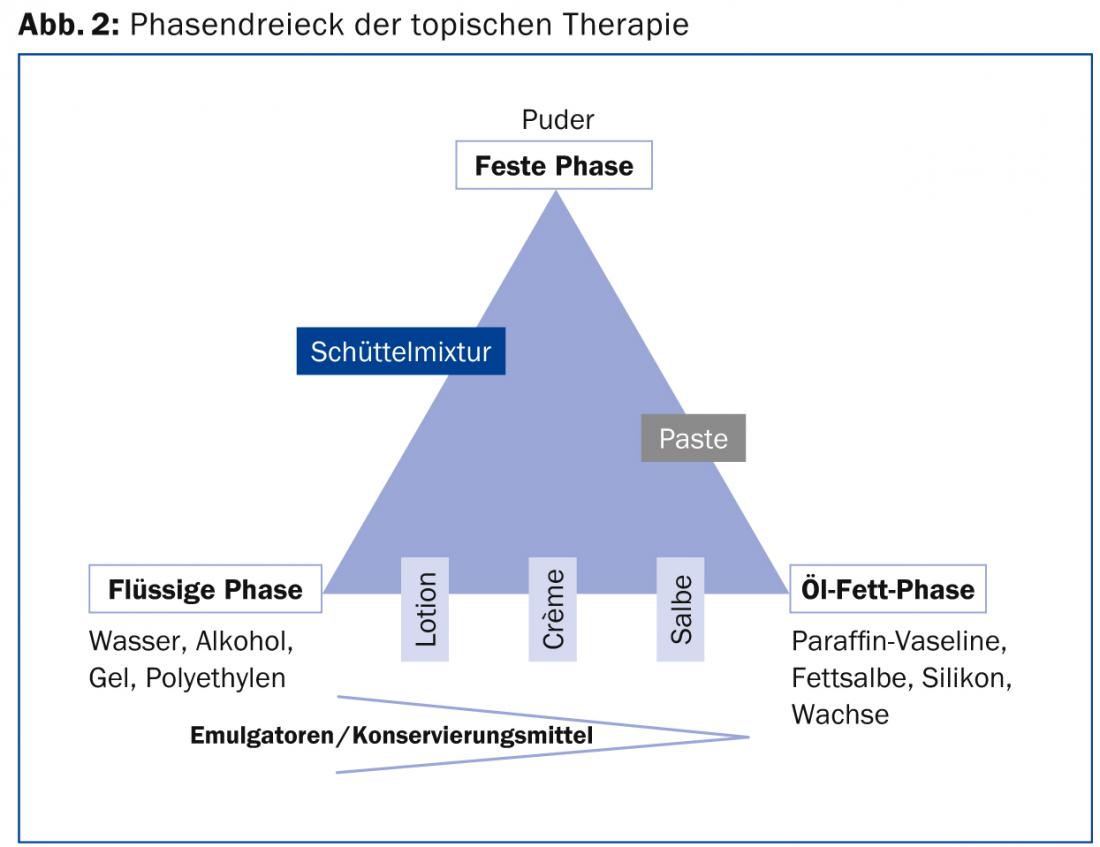

The most important sole or additional cause of age pruritus is dry skin. Therefore, special attention must be paid to a good and sufficient refatting care therapy. Since there is usually a genetic and age-related dehydration of the skin with changes in the skin lipids and the skin barrier, the re-fattening and hydration must be done externally. External preparations containing potentially irritating and sensitizing additives should be avoided. Especially fragrances, preservatives and various natural additives can easily penetrate the disturbed skin barrier in aging skin and disturb, damage or stimulate the living skin cells in the epidermis and also the immune cells in the skin. An inflammatory skin reaction is the result, which in turn intensifies the itching. Therefore, my maxim is to use topical care products, such as creams, ointments or soap shampoos, which contain a minimum of additives. Less is more! It can be assumed that water-in-oil emulsions (ointments) usually contain fewer additives (emulsifiers, preservatives) and are better refatting than oil-in-water emulsions (creams, lotions). But compliance is usually better in the patient with less fat bases, and therefore sometimes a compromise must be found. The principle is that oily ointments should be used for dry, cracked, and chronic eczematous changes, and less oily, watery creams and lotions should be used for more acute-subacute, weeping changes (Fig. 2).

Topical therapy stands and falls with the patient’s compliance. Most topical therapies fail due to underapplication of topical products. It takes great discipline on the part of the patient; the doctor and nurses must support and help the patient. Older patients in particular often have limited mobility and are unable to cream themselves. As a rule of thumb, 30 g of care cream should be used per application to the whole body, i.e. for re-lubrication of the whole body twice a day (which corresponds to normal re-lubricating therapy), 500 g of cream or ointment is optimally required every 1-2 weeks. It is also important to inform patients to avoid alcohol-containing externals or frequent showering. This dries out the skin once again and makes the itching worse in the long run, despite short-term relief.

When the skin care therapy has been optimized, additional measures can be combined. This includes a combination of sedative and non-sedative antihistamines. It must be emphasized, however, that no study has yet been able to clearly prove that antihistamines can really reduce chronic itching. Topical corticosteroids are appropriate for eczematous, inflammatory conditions, and perhaps the calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) for prolonged use. However, corticosteroids should be avoided in cases of pruritus without visible skin inflammation (e.g., pure xerosis cutis), since the primary anti-inflammatory effect cannot take effect here. Long-term use, even of weak steroids, should be avoided as this can negatively affect skin atrophy, microbial skin colonization, and sometimes diabetic metabolic status. The benefits and side effects are out of proportion here. I recommend an interval therapy with application of corticosteroid externals regularly once or twice a week, e.g. Saturday and Sunday, and in between a pure care therapy.

Systemic use of doxepin (Sinquan®) or mirtazapine (Remeron®), which are primarily antidepressants but apparently can also affect peripheral nerve fibers and thus itch, is certainly a good alternative. Doxepin may be tried in doses of 10-50 mg in the evening. However, it must be noted that doxepin is sedating and also has anticholinergic effects with, for example, urinary retention or problems in glaucoma patients. Also, sometimes ultraviolet therapy can relieve itching. I had good success with UV-A/UV-B 311 nm combination therapies. Itching based on kidney and liver problems must be specifically addressed.

Literature:

- Weisshaar E, et al: European guideline on chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92: 563-81.

- Sun YG, et al: Cellular basis of itch sensation. Science 2009; 325: 1531-1534.

- Ward JR, Bernhard JD: Willan’s itch and other causes of pruritus in the elderly. Int J Dermatol 2005a; 44: 267-273.

- Ward S: Eczema and dry skin in older people: identification and management. Br J Community Nurs 2005b; 10: 453-456.

- Fenske NA, Lober CW: Skin changes of aging: pathological implications. Geriatrics 1990; 45: 27-35.

- Cohen KR, et al: Pruritus in the elderly: clinical approaches to the improvement of quality of life. P T 2012; 37: 227-239.

- Irvine AD, Mclean WH: Breaking the (un)sound barrier: filaggrin is a major gene for atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126: 1200-1202.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Pruritus in the elderly is usually a combination of different causes. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach and collaboration between the different physicians and, above all, the nursing staff, the patient and his family are essential.

- This takes a lot of time and effort, but it is worth it, as the reduction of itching can significantly improve the patient’s quality of life and overall health.

- Special attention must be paid to the re-fatting care therapy and reduction of dry skin.

- Correct application and compliance must be constantly monitored. Time-consuming persuasion and assistance are essential.

- Constant re-evaluations of possible additional factors, hidden diseases or drug therapy must be performed in chronic pruritus.

A RETENIR

- Un prurit chez la personne âgée est le plus souvent la combinaison de différentes causes. The result is that a multidisciplinary approach and collaboration between different physicians and, above all, between the medical staff, the patient and his family are indispensable.

- Cela nécessite beaucoup de temps et d’efforts, mais en vaut la peine étant donné que la réduction des démangeaisons peut améliorer considérablement la qualité de vie et l’état de santé général du patient.

- À cet égard une attention particulière doit être portée sur les soins relipidants et la réduction de la sécheresse cutanée.

- L’utilisation correcte et l’observance doivent être contrôlées en permanence. Un travail de persuasion et une aide de longue haleine sont indispensables.

- Des réévaluations permanentes des facteurs supplémentaires possibles, des pathologies sous-jacentes ou des traitements médicamenteux doivent être effectuées dans le prurit chronique.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(2): 10-16