Allergic diseases are among the most common diseases worldwide, even if the relevance is assessed differently and many complaints are subsumed under the term “allergy”. Fundamental to the diagnosis of allergy is the identification of the relevant allergen source and allergens. A correct diagnosis is the cornerstone for successful treatment. In this paper, the authors address examples of selected IgE-mediated inhalant and food allergies (NMA).

Epidemiological data collected in Switzerland since 1926 show a significant increase in pollen allergy from <1% at that time to >12% in the 1990s and a leveled off level around 20% since then. In recent studies from Austria and Germany, more than half of the general population shows sensitization to at least one inhalant allergen [1]. The direct and indirect socioeconomic costs resulting from allergies are considerable. An estimate in 2000 put the cost in Switzerland at about 1 billion Swiss francs [2]. New information does not appear to be available. Depending on the type and severity of an allergy, those affected are massively restricted in their quality of life. Thanks to OTC (“over the counter”) products, the majority of patients initially treat themselves or rely on non-conventional treatments. Unfortunately, few are aware that, in addition to prevention, individualized therapy is useful and allergen-specific treatments are possible.

Aspects of aero- or inhalation allergies

Aeroallergies such as pollen allergy trigger inflammatory changes at the contact sites of mucous membranes such as the upper and lower respiratory tract. Typically, most affected individuals initially present with rhinoconjunctivitis, usually with bilateral eye involvement and sneezing attacks. However, pharyngeal itching, which extends to the middle ear and is perceived as very unpleasant, is also part of the symptom spectrum [3]. More than half of pollen allergy sufferers develop bronchial hyperreactivity with asthmatic symptoms after prolonged exposure to allergens or even after years, manifesting during physical exertion, exertion or after respiratory infections. With seasonal allergen exposure (pollen, seasonal molds), symptom onset is virtually always acute – from one hour to the next. Year-round allergen sources, on the other hand, such as dust mites, some animals or indoor fungal infestations, usually manifest themselves subliminally with a gradual onset.

The very largest proportion of seasonal complaints is caused by pollen from wind-pollinated plants. In Switzerland, grass, birch and ash pollens are generally significant, as well as mugwort (e.g. Valais) or other pollens depending on the region. The main pollen allergens of hazel, alder, beech, and oak show great homology to birch pollen and are cross-reactive with each other [4]. Perennial symptoms are often triggered by house dust and other mites or pets [5]. Undoubtedly, occupational allergies must also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Aspects of food allergies

Relevant food allergies (NMA) are registered more frequently in the first months and years of life and decrease with age. NMA is thought to affect approximately 6% of children and 3-4% of adults [6], with different foods (NMs) identified as triggers. While in children cow’s milk, hen’s egg, peanut, fish, soy and wheat are considered the most common triggers of NMA, in adults cross-reactions due to structural protein sequence homologies between inhalant and food allergens play a role. In particular, tree nuts, all fruits, various vegetables and shellfish are common causes of NMA. The affected persons do not necessarily have to suffer from pollinosis or other inhalation allergies, but they “merely” exhibit sensitization to the relevant lead allergen.

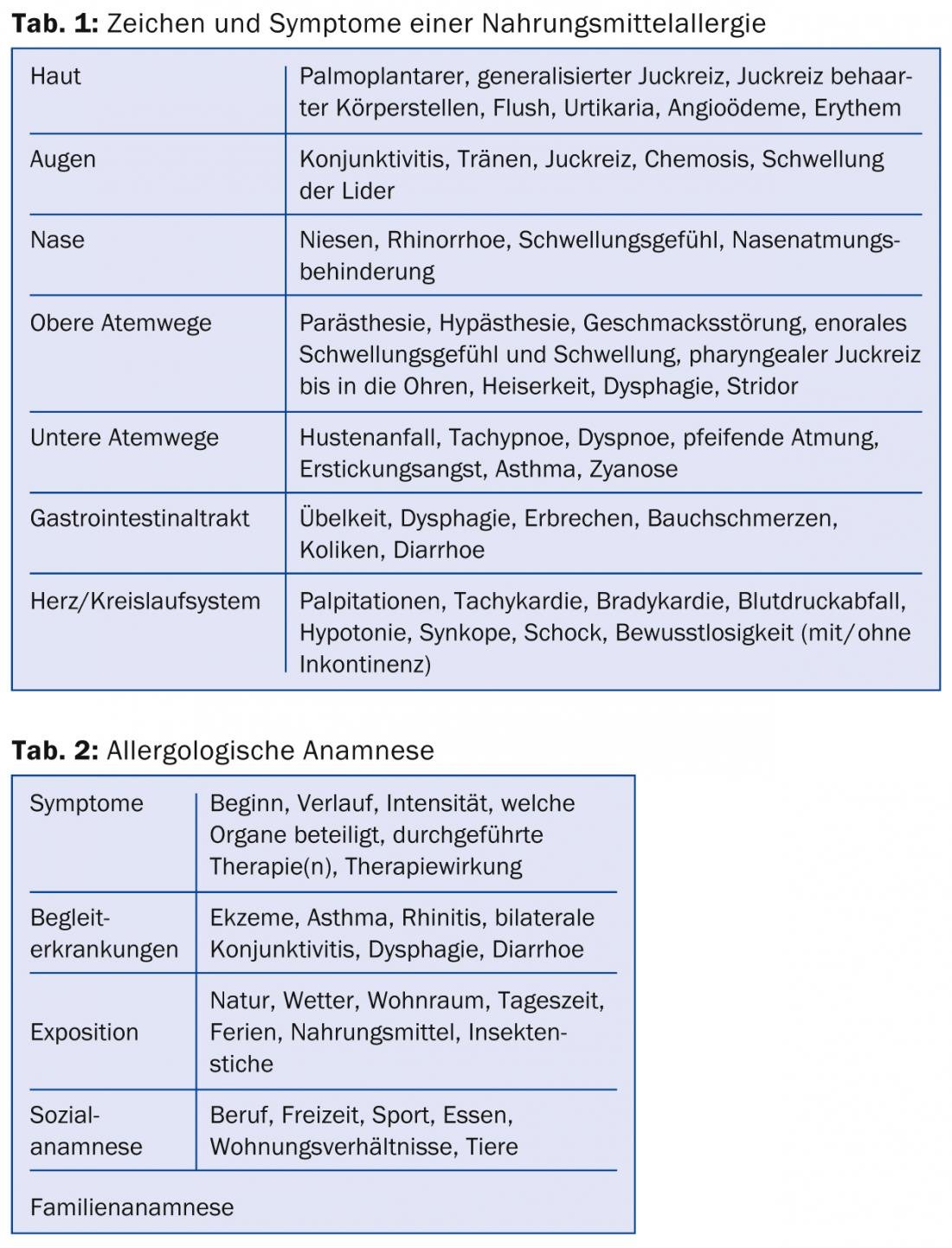

Symptoms of NMA can manifest themselves variably (Tab. 1) . They range from mild local contact reactions to severe anaphylaxis. IgE-mediated NMA usually manifest rapidly and already during eating in the form of enoral itching, swelling, “aphthae formation”, blisters or biting on the lips, buccal mucosa, tongue or throat. This phenomenon, which can be elicited in about half of pollen allergy sufferers, is called oral allergy syndrome [7]. The most common triggers of this NMA are apples and hazelnuts (cross-reaction with birch pollen). Since the causal allergens are neither heat nor digestion stable, symptoms are usually limited to the mouth and throat. Thus, these foods can be enjoyed heated or cooked virtually always without problems.

However, NMAs can also trigger systemic reactions in the skin, mucous membranes, gastrointestinal or respiratory tract, as well as in the circulatory system (Tab. 1). Peanut, tree nuts, seeds and kernels contain storage or lipid transfer proteins,

which are heat and digestion stable, which can lead to systemic and even severe general reactions. Thus, Ara h2 is considered a marker allergen for peanut allergy, which can lead to systemic reactions. Lipid transfer proteins are major allergens and are found in various fruits such as apple, peach, apricot, cherry, and plum; usually affected individuals are not allergic to birch pollen.

Medical history

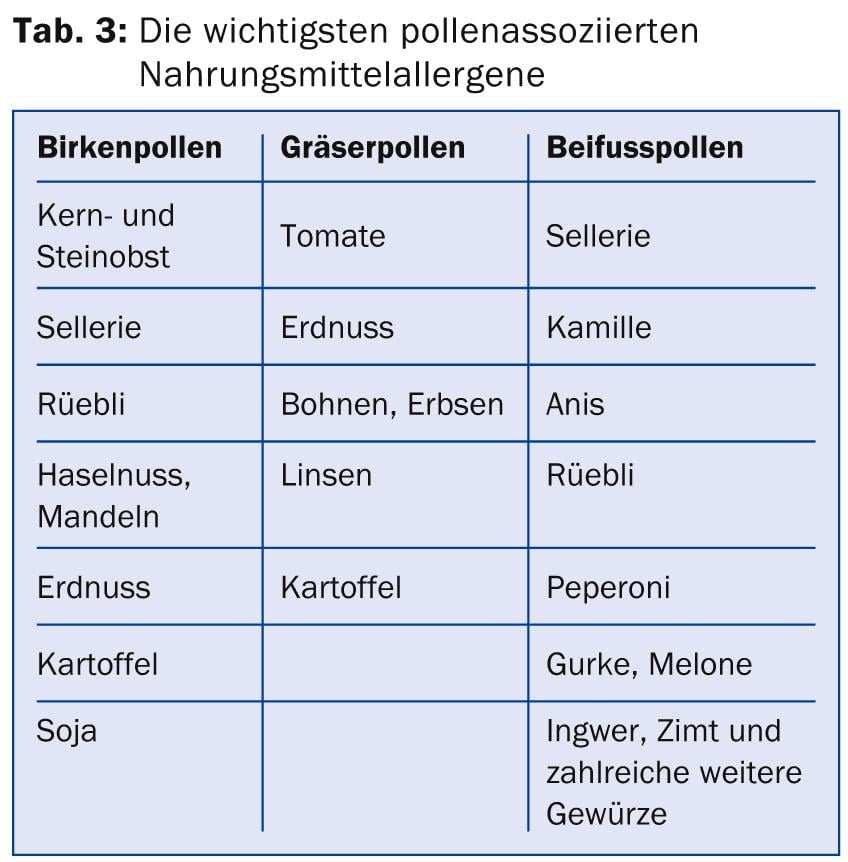

Ana-mnesis plays a key role in the clarification of allergies. Skin testing and serological determinations are further cornerstones in the diagnosis, but the results can only be interpreted correctly on the basis of the medical history. While local reference often plays a role in inhalant allergies, the temporal interval after eating and the onset of symptoms is directional in NMA. Keeping a symptom diary can be useful in this regard. Pollen allergy sufferers can, for example, download a free app (“e-symptoms App”) to their smartphone. The important points of an allergological history are summarized in Table 2.

Skin testing

Skin testing with various standardized allergen solutions (Fig. 1) can be used to clarify most inhalation allergies as well as NMA.

Detection of sensitization to a food is usually more accurate when fresh, native foods are used and tested by prick-to-prick. It is important to compare and evaluate the wheal and erythema reaction with the suspected NM 15-20 minutes after application with the positive control (e.g., histamine) [8].

Prick tests are usually sensitive enough. In contrast, specificity is limited because not every positive skin test reaction is clinically relevant. Therefore, always refer to the clinical symptoms when making an assessment. It is important that oral antihistamines are discontinued five, preferably seven, days prior to testing, otherwise interpretation is hampered. Likewise, other medications such as H2 receptor blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, or antiemetics may interfere with test results.

Serology detection of specific IgE

Specific IgE (sIgE) antibodies against many allergen sources as well as major and some important minor allergens can be determined by various analytical methods such as ELISA. In contrast to the skin test, only free sIgE circulating in the blood are detected serologically. The serological tests are generally less sensitive than the skin test [9]. In recent years, the determination of sIgE against recombinantly produced single allergen components (component-based allergy diagnostics) has become increasingly important. It has been shown that molecular diagnostics can be used to make more precise statements about the relevance of an allergen in the case of both inhalation allergies and NMA, or to better assess the risk of general reactions [10].

Component-based allergy diagnostics using the example of pollen allergy

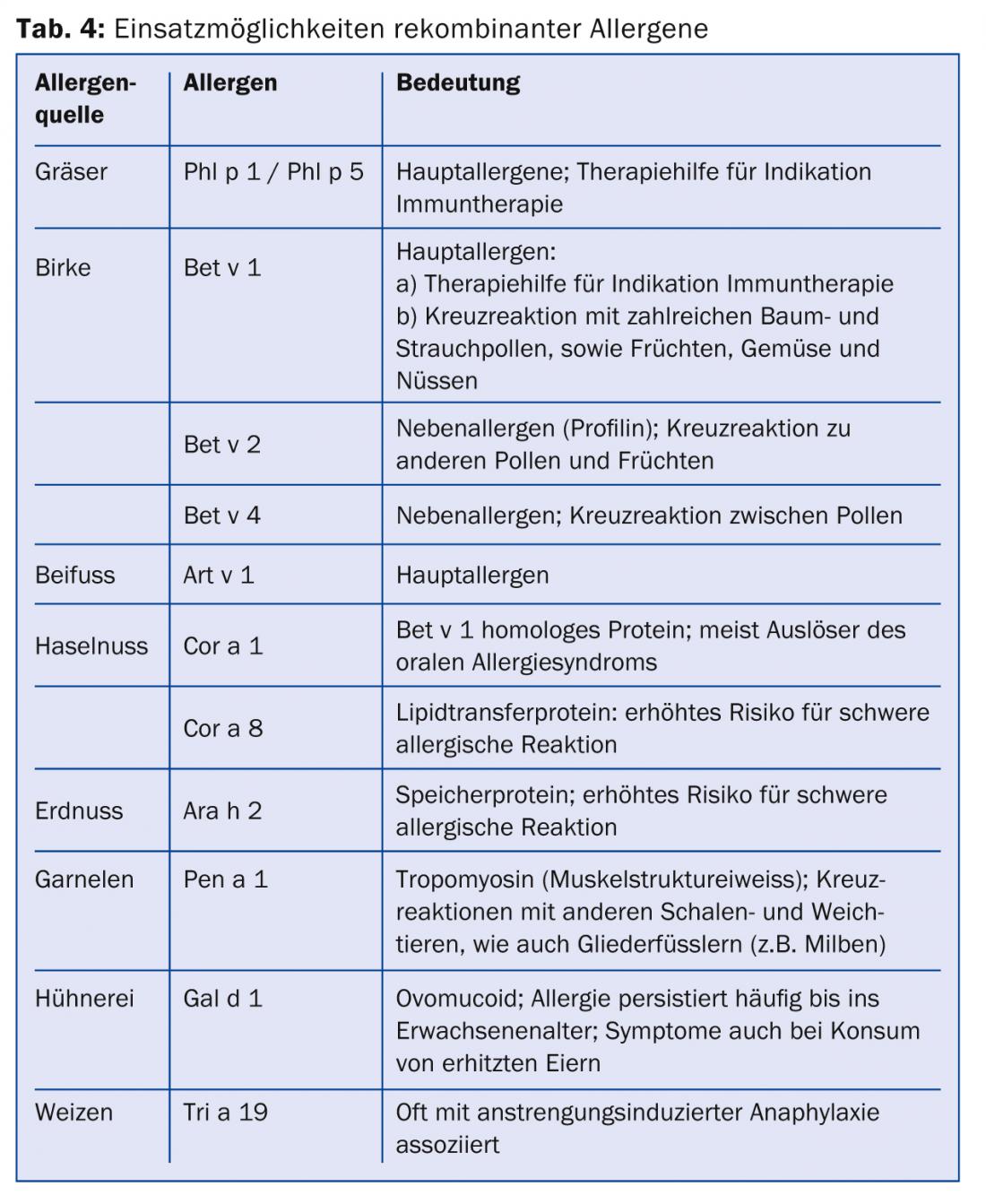

In pollen allergies, sIgE can be determined for major and minor allergens. While major allergens are characteristic of an allergen source, some minor or secondary allergens have cross-reactive properties and are also often clinically less important [11]. In the indication of specific immunotherapy, this circumstance must be taken into account, as the therapy extracts are standardized to the main allergens. Of particular concern for Switzerland are the major allergens of birch pollen (Bet v 1), grass pollen (Phl p 1, Phl p 5) and ash pollen (Ole e 1 [Olivenpollen-homologes Allergen]).

Component-based allergy diagnostics using the example of a NMA.

NMA can also be better assessed thanks to molecular diagnostics. Numerous plant foods are cross-reactive to the major allergen of birch pollen and can evoke an oral allergy syndrome from consumption of a fresh or raw food (Table 3).

Sensitization to a storage protein (e.g., Ara h 2 from peanut) or lipid transfer protein (e.g., Pru p 3 from peach) tends to indicate a higher risk for potential general reactions, although this should be assessed in the context of the clinic [12]. Several different allergens can be found in the same food, e.g. apple or peanut, which can give rise to different allergic symptoms. Thus, in addition to storage proteins (Ara h1-3), peanuts also contain Ara h8, which is homologous to Bet v1 and clinically induces an oral allergy syndrome. Table 4 lists further examples of important allergens.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Allergy diagnostics is based on the patient’s medical history and the resulting further clarifications such as skin testing and blood tests.

- Prick testing is an easy to perform and inexpensive test with good sensitivity. The determination of specific IgE antibodies against allergens should primarily be performed in addition to skin testing or if skin testing is not possible.

- Both skin testing and serology must always be interpreted in conjunction with the medical history and clinic; sensitization is not always synonymous with (clinically relevant) allergy.

- The determination of specific IgE antibodies against recombinant allergens allows better statements about the course and severity of an allergy and thus also the determination of treatments such as specific immunotherapy.

Lukas Jörg, MD

Literature:

- Schmitz R, et al: Patterns of sensitization to inhalant and food allergens – findings from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2013; 162(3): 263-270.

- Müller U, et al: Good Allergy Practice. Swiss Medical Journal 2000; 81: 41.

- Wallace DV, et al: The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy ClinImmunol 2008; 122(2 Suppl): S1.

- Egger C, et al: The allergen profile of beech and oak pollen. Clin Exp Allergy 2008; 38: 1688-1696.

- Dürr C, Helbling A: Allergies to animals and fungi. Therapeutic Review 2012; 69 (4): 253-259.

- Sicherer SH, Sampson HA: Food allergy. J Allergy ClinImmunol 2006; 117: S470.

- Kleine-Tebbe J, Herold DA: Cross-reactive allergen clusters in pollen-associated food allergy. Dermatologist 2003; 54(2): 130.

- Ruëff F, et al.: Skin tests for diagnostics of allergic immediate-type reactions. Guideline of the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Pneumology 2011 Aug; 65(8): 484-495.

- Hamilton RG, Franklin Adkinson N: In vitro assays for the diagnosis of IgE-mediated disorders. J Allergy ClinImmunol 2004; 114: 213.

- Giorgio C, et al: A WAO – ARIA – GA²LEN consensus document on molecular-based allergy diagnostics. World Allergy Organization Journal 2013; 6: 17 (3 October 2013).

- Sastre J, et al: How molecular diagnosis can change allergen-specific immunotherapy prescription in a complex pollen area. Allergy 2012 May; 67(5): 709-711.

- Sastre J: Molecular diagnosis in allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2010 Oct; 40(10): 1442-1460.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(2): 12-15