Therapy of PD must always be individualized and its onset should take into account the patient’s level of suffering. Initially, almost all antiparkinsonian drugs can be used with success, but levodopa should still be preferred in the elderly and/or polymorbid, as well as in parkinsonisms. When motor fluctuations occur, many treatment strategies, some of them invasive, are available. Special attention must be paid to non-motor symptoms; only some of them improve after administration of dopaminergics, some do not at all, and some even get worse with antiparkinsonian drugs. Further measures are often indicated.

It is a common misconception that therapy for Parkinson’s disease is simple. We know the “old” drugs well, the pharmaceutical industry has “fortunately” hardly brought any novelties to the market. Nevertheless, individualization of treatment remains difficult. Are there general rules that make our work easier?

After the diagnosis of Parkinson’s syndrome is certain, we must first ask ourselves whether a “classic”, idiopathic form is present. A neurologist should be consulted for this. If the answer is positive, the following decisions must be made: When to treat and how to start? What to do when the first motor fluctuations appear? When are the more “aggressive” therapies indicated? Can we alleviate the nonmotor disturbances of the disease, and if so, how? And what should we do when our patients actually present with Parkinsonism? Thoughtful, individualized answers to these questions will allow us to give patients the best possible quality of life for as long as possible.

When and how to treat?

Today, it is often claimed that starting treatment as early as possible may be beneficial. There is evidence that drugs, such as rasagiline, delay disease progression (although this has not been clearly confirmed to date). Moreover, early treatment improves patients’ quality of life sooner. In addition, the preventive effect of later treatment on the development of motor fluctuations has not been proven. But treating earlier also means an earlier risk of side effects – and their impact on quality of life has been little studied. So how should you proceed? The old golden rule still applies: the timing of the start of therapy should be discussed in detail with the patient. His or her wishes, social and professional situation, and level of suffering must be taken into account.

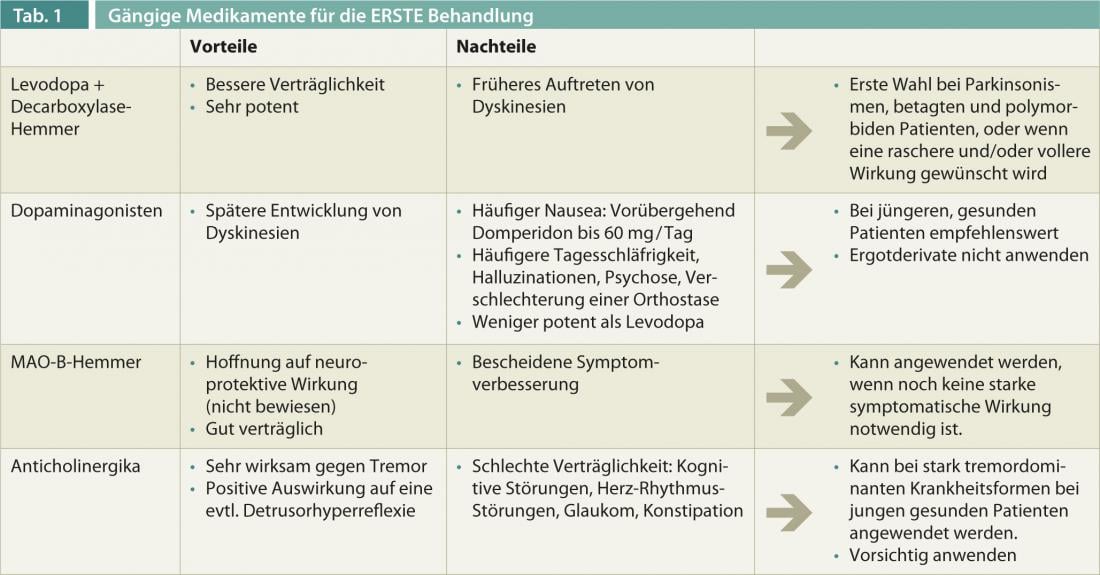

After the decision is made, the question comes to the forefront, “Treat with what?” Does one put one’s faith in the hope of neuroprotection? Is rapid symptom improvement desired by the patient? Do pre-existing non-motor symptoms or other atypia indicate parkinsonism? Is there any polymorbidity? Is the tremor the primary concern for the patient? The possible strategies for initial treatment are summarized in Table 1 .

As a general rule, the initial dose must be as small as possible and any dose increase must be very slow. It is not uncommon to start with twice-daily administration, e.g., at 8 a.m. and 2 p.m.; more frequent administration can be given later if necessary. Starting treatment with sustained-release drugs, COMT inhibitors, or drugs with long half-lives offers little advantage because the effects of standard drugs last longer initially and nocturnal or early morning motor symptoms usually do not yet occur. Also, the hypothesis that continuous dopaminergic stimulation could delay the development of dyskinesias and other motor fluctuations has never really been confirmed: Effect fluctuations do occur later with this – whether they were prevented or simply well treated remains to be seen.

For parkinsonisms and polymorbidities: levodopa

Unfortunately, resistance to therapy is often expected when parkinsonism is suspected. Nevertheless, many of these patients show at least partial responsiveness to dopaminergic therapy in the early years. Levodopa is the drug of first choice here. In parkinsonisms, the early onset of serious nonmotor symptoms (such as symptomatic orthostasis or cognitive and psychiatric disturbances) is very likely, whereas the risk of dyskinesia is minimal. Because levodopa has a lower effect on hypotension, hallucinations, and psychosis than the other antiparkinsonian drugs, it must be preferred for parkinsonisms. The same is true for elderly and polymorbid patients, whose susceptibility to side effects is well known. These patients are often treated by complicated therapy; the non-interaction of levodopa (an amino acid) is an additional advantage here.

First fluctuations

After a few years of relatively simple treatment, motor fluctuations occur in most patients. The duration of drug action becomes shorter (“wearing off”) when the minimum effective dose of levodopa is administered more frequently than every four hours. Parkinson’s symptoms may also occur at night and painful dystonia may accompany the akinetic phases. The cause? Levodopa, which has a short half-life, is simply no longer “stored” by the brain.

The simplest effective measure would then be to administer levodopa more frequently, at a frequency that takes into account the duration of action observed by the patient. If the times of intake are not to be changed, we can administer levodopa retard; these can be associated with standard levodopa to reduce any latency of action delay. Alternatively, additional medication (with COMT inhibitors, dopamine agonists, or MAO-B inhibitors) is conceivable. When additional supplements are given, a slight reduction in levodopa is recommended to avoid an increase in dyskinesias.

These involuntary movements have since become frequent (even in patients treated with dopamine agonists, although somewhat later). The best strategy against this is to keep the dose of medication as small as possible. An exception is the (rare) biphasic dyskinesias that accompany the onset and end of action. There, surprisingly, a dose reduction will lead to an increase in involuntary movements: In contrast, a dose increase and discontinuation of sustained-release drugs will cause a paradoxical improvement.

For dyskinesia, amantadine is also often chosen, but its effect is often only noticeable for a few months.

Stronger fluctuations

Over time, the phases of recurrence of Parkinson’s symptoms become more irregular. Although one can address the unpredictable akinesias by using a rapidly absorbable form of levodopa that must be dissolved in water. However, due to the longer preparation time, the advantages of faster absorption are usually lost. To this end, dyskinesias often increase and may be dose-limiting, possibly along with other side effects.

In advanced Parkinson’s disease with severe fluctuations and various non-motor accompanying symptoms, “pump therapy” is available in addition to Parkinson’s surgery if conventional (oral and transdermal) medications have been exhausted. The theoretical background for apomorphine administered subcutaneously via pumps and levodopa/carbidopa gel administered enterally (via gastrojejunostomy) is the concept of continuous dopaminergic stimulation.

The dopamine agonist apomorphine has a very potent antiparkinsonian effect. In the case of subcutaneous injection, the effect occurs after about ten minutes, which is used, for example, in the use of the apomorphine pen(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Apomorphine pen

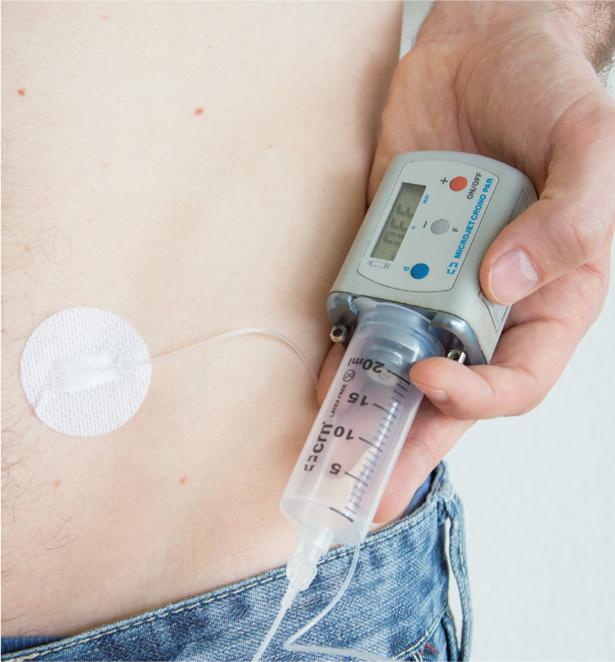

Apomorphine administration by pump(Fig. 2) is appropriate for patients who suffer from on-off problems and who experience concomitant dyskinesia during periods of good drug efficacy, or when the apomorphine pen is used very frequently.

Fig. 2: Apomorphine pump

The external pump controls the continuous apomorphine infusion. As a result, off times are reduced by 50-70%. With concomitant savings of oral levodopas, dyskinesias are often significantly reduced as well.

Moreover, a combination preparation of levodopa and carbidopa in the form of a viscous gel has been available for years, which is continuously delivered directly into the small intestine by means of a body-worn pump(Fig. 3) via a percutaneous gastrojejunal tube (JET-PEG).

Fig. 3: Duodopa

®

-pump

Significantly improved Parkinson’s symptoms over a period of up to seven years were demonstrated under this treatment: Decrease in fluctuations and dyskinesias, reduction in daily off, improvement in gait disturbances and “freezing”, decrease in falls. Non-motor symptoms also improved, and many patients showed increased quality of life and independence.

In this issue, PD Dr. med. Christian Baumann, Zurich, takes a closer look at functional neurosurgery (article on the benefits of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease). Here, it should only be emphasized that the best effect of surgical interventions is equal to the best effect of drugs. So where is the difference? The effect remains for 24 hrs during the operation, in addition, a reduction of possible side effects caused by medication is made possible. However, the fact that the best effect of medication is not surpassed means that therapy-resistant Parkinsonisms are unfortunately hardly improved even by surgery.

Nonmotor symptoms: reduction of medication?

Patients with Parkinsonism are not the only ones who suffer from non-motor symptoms. Even if patients are “lucky” enough to be affected by the “real” PD, their treatment is mainly complicated by non-motor symptoms.

Rarely pronounced at the beginning (otherwise this indicates parkinsonism), these complaints increase during the course and are hardly improved or sometimes even worsened by antiparkinsonian therapy. Thus, dopaminergics exacerbate or cause hallucinations and psychosis: a typical example is dopamine dysregulation syndrome (with behavioral disturbances such as pathological buying or gambling behavior, tendency to abuse drugs, hypersexuality, hypomania). The total dose of antiparkinsonian drugs must be reduced in the case of psychiatric manifestations and monotherapy with levodopa must be sought, since this exerts a lower effect on the mesolimbic system than the other dopaminergic drugs. If the use of neuroleptics is nevertheless necessary, only clozapine and quetiapine in very low doses can be considered. Levodopa monotherapy should also be sought in cases of dementia and symptomatic orthostasis. In orthostasis, possible treatments include the use of domperidone in an attempt to partially inhibit the peripheral effects of dopaminergics. Also an increased daytime sleepiness – especially to be considered with drivers – can be caused by the disease, but is also intensified or caused by the drugs, especially pramipexole and ropinirole : Special attention (and drug reduction!) is required here.

An increase in antiparkinsonian drugs, on the other hand, can alleviate numerous other symptoms, e.g., the relatively frequent depression: the enhancement of everyday life through optimized medication will brighten the patient’s mood; moreover, the organic component of the depression is improved by the dopaminergic drugs. Likewise, the frequent pain symptoms, which may be aggravated or even caused by the disease, will usually be alleviated by optimizing the medication. The same is true for the eventual restless legs symptomatology, sexual dysfunction, salivation and frequent constipation.

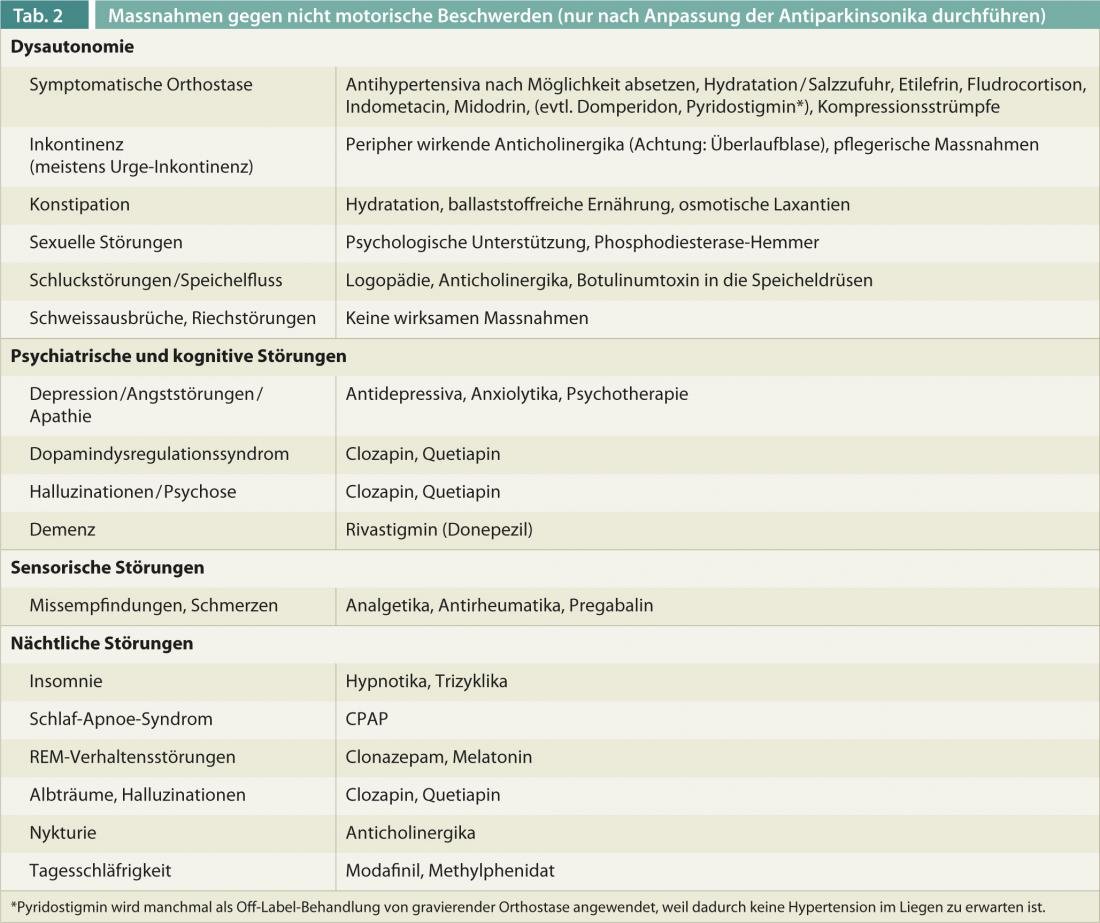

After adjustment (dose increase or reduction or simplification) of antiparkinsonian medications is made, numerous nondopaminergic medications or nursing measures can be used to try to control these bothersome symptoms(Table 2). Nevertheless, these disorders are probably the most important cause of disability in advanced disease.

Experience shows that the constellation of complaints that patients present is very complex and individual. A high degree of flexibility and a multidisciplinary approach in close collaboration with various specialists can make it possible to give patients a satisfactory quality of life for as long as possible.

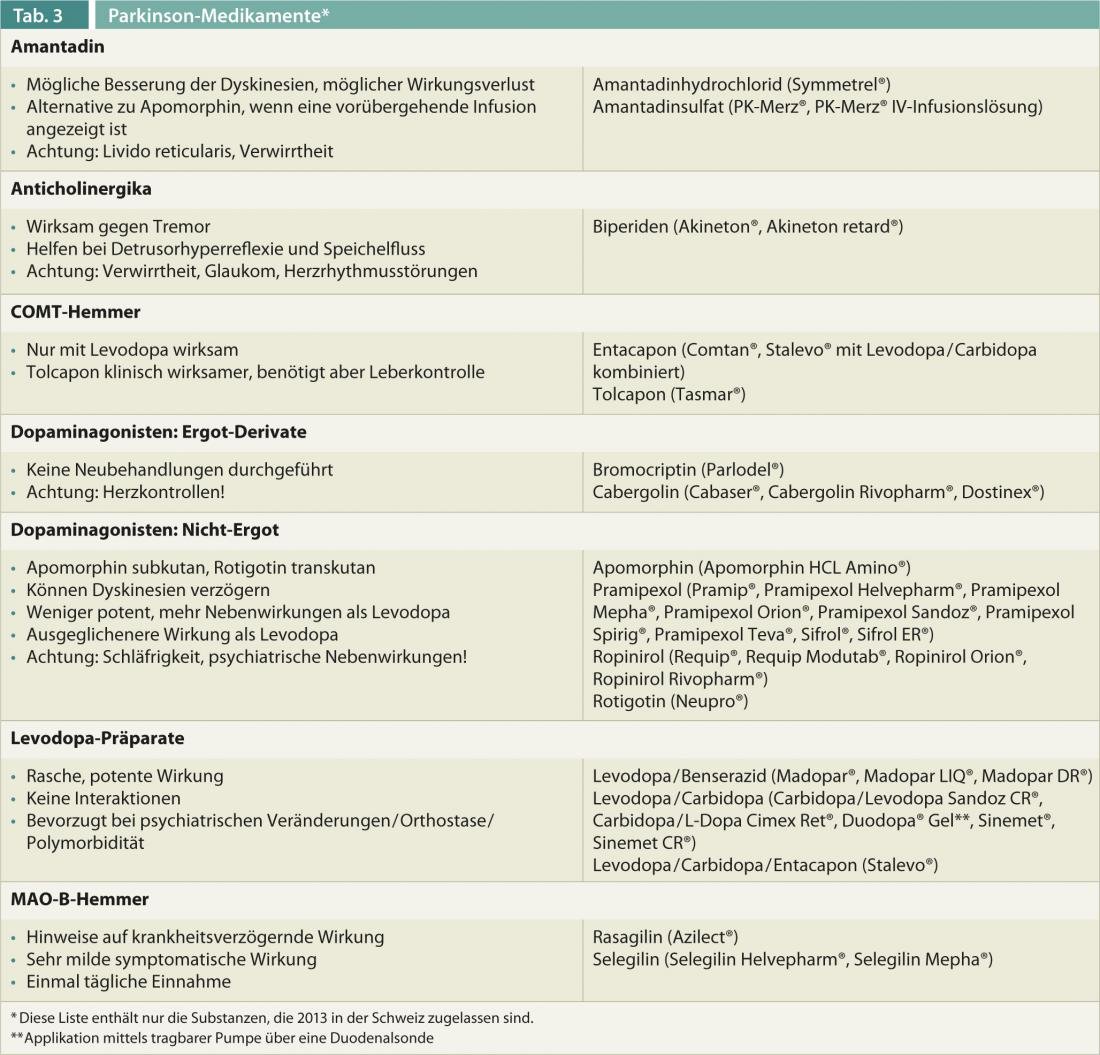

An overview of the characteristics of different Parkinson’s drugs is given in Table 3.

Literature list at the publisher

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2013; 11(4): 10-15.