The causes of chest pain are extremely varied, can affect different organ systems in the chest and – depending on the cause – are absolutely harmless or acutely life-threatening. Fortunately, in the general practitioner’s office or the emergency department, by means of targeted questioning, clinical examination and the use of selected additional tests (electrocardiogram, blood test, imaging), approximately 90% of all situations can be classified as harmless without the need for further clarification. The primary objective is to exclude dangerous circumstances through targeted risk stratification.

Chest pain is a common problem. In the Swiss population as a whole, an average of 1-2% of all respondents report having experienced chest pain in the past four weeks (women more often than men). It is estimated that 20-40% of the general population experiences chest pain at least once in their lifetime. These complaints frighten patients and, accordingly, this reason for consultation is very common in the family practice, accounting for 4-10% of all visits to the doctor.

In particular, acute chest pain due to cardiovascular pathology is a serious emergency situation that must be recognized quickly and treated without delay. Despite impressive progress in recent decades, acute coronary syndromes/heart attacks, aortic dissections, pulmonary embolisms, new-onset arrhythmias, hypertensive hazards/crises, and decompensated heart failure are still conditions that contribute substantially to mortality (and morbidity) in the overall Swiss population [1]. Thus, even today, the average myocardial infarction has an early (in-hospital) mortality rate of more than 4% [2]. Here it is important to quickly initiate a specific therapy. Any delay can have fatal consequences for the further course of the disease; for example, in the case of aortic dissection, a quarter of all patients die within the first 24 hours after the event (1% mortality rate per hour!), and in the case of myocardial infarction, delayed opening of the affected coronary artery leads, among other things, to an irretrievable loss of valuable heart muscle tissue (consequence: heart failure). A well-functioning network of primary care providers, specialists, emergency services and hospitals is central to efficient patient care here.

Acute heart attack

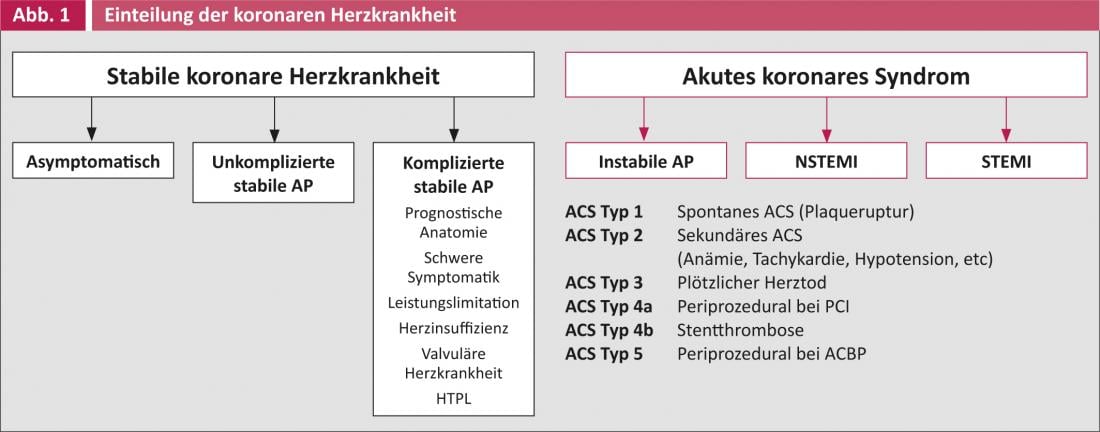

Coronary artery disease is a potentially dangerous cause of chest pain and affects a majority of cardiovascular emergencies. Typical initial manifestations are: acute myocardial infarction (40%), stable angina (40%), or sudden circulatory arrest/cardiac death (20%). Coronary artery disease thus includes a chronic form of manifestation (stable angina), but can also occur acutely (acute coronary syndromes) (Fig. 1). The latter can be divided pathophysiologically into five types, the most common being spontaneous rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque in a coronary artery with subsequent clot activation and thrombotic occlusion (ACS type 1).

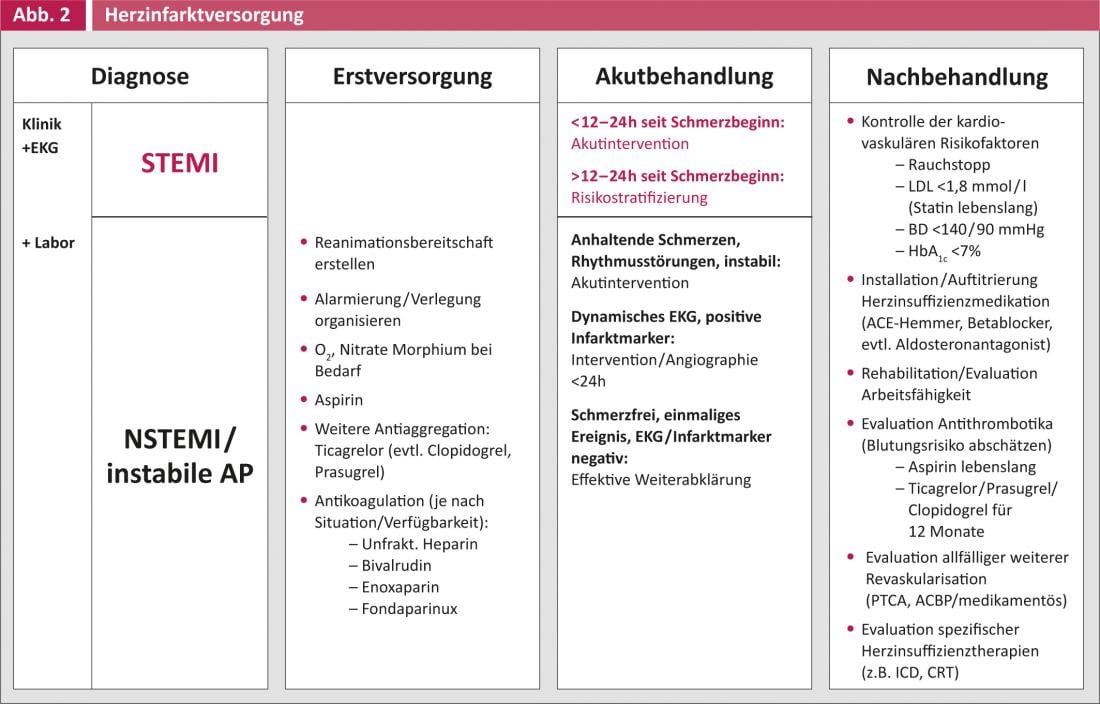

For clinical practice, the classification into unstable angina/NSTEMI (non-ST elevation myocardial infarction) and STEMI has proven useful because the treatment strategy differs significantly. Myocardial infarction care (Fig. 2) can be divided into different phases, with each phase having specific medical care characteristics, different diagnostic/therapeutic time windows, and communication interfaces [3].

Treatment strategy/diagnostics

The diagnosis of acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is purely electrocardiographic (laboratory and imaging usually unnecessary) and should usually be made within the first ten minutes of initial medical contact (primary care physician, on-site ambulance, emergency department). Acute intervention in the nearest cardiac catheterization laboratory via direct referral by the primary medical contact is reasonable within the first 12-24 hours after the pain event. In this time window, every minute counts, and the patient should receive acute treatment as soon as possible. The goal of optimal care is to perform a procedure within the first 60-90 minutes of initial medical contact.

In non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina pectoris, adequate acute treatment results from initial risk stratification: Thus, a single pain event with negative ECG findings and no increase in laboratory markers of infarction may well be electively further clarified in the course (stress test, imaging, etc.), whereas a patient with persistent pain despite initial treatment even without ST-segment elevations should be directly referred to catheter-based acute intervention.

Initial drug treatment and follow-up treatment

The initial drug treatment of STEMI differs little from that of NSTEMI/unstable angina, with the only difference being the antithrombotic therapy protocols. The use of modern drug, interventional, and logistic treatment strategies can reduce mortality and morbidity in the early phase of myocardial infarction.

However, for a sustainable treatment success, the follow-up treatment is of central importance: The initial intervention only treats the acute problem (myocardial infarction), the disease (coronary heart disease/atherosclerosis) is not cured. Accordingly, long-term consistent control of cardiovascular risk factors according to secondary prevention target values is important. The use of antithrombotic therapy during the course often requires a combination of drugs adapted to the patient (depending on the risk of bleeding, simultaneous indication for oral anticoagulation, pending surgery, optimal duration, etc.) – in this case, the optimal solution usually results from a direct consultation between the post-treatment physician and the specialist/cardiologist.

Patients who develop heart failure require increased attention. These patients find it particularly difficult to return to everyday life after a heart attack, are limited in their physical capacity and have a poor prognosis (mortality/morbidity). Although current medications can be effective, installation of extended heart failure therapy is a lengthy process over several weeks (uptitration ACE inhibitor/betablocker, clinical/laboratory chemistry checks, possibly implement aldosterone antagonist, short-/long-term diuretic use, etc.). In addition, it is important to identify patients who would benefit from specific heart failure therapies (e.g., implantable defibrillator [ICD], cardiac resynchronization therapy [CRT], drug/mechanical circulatory support, heart transplantation).

Stable angina pectoris

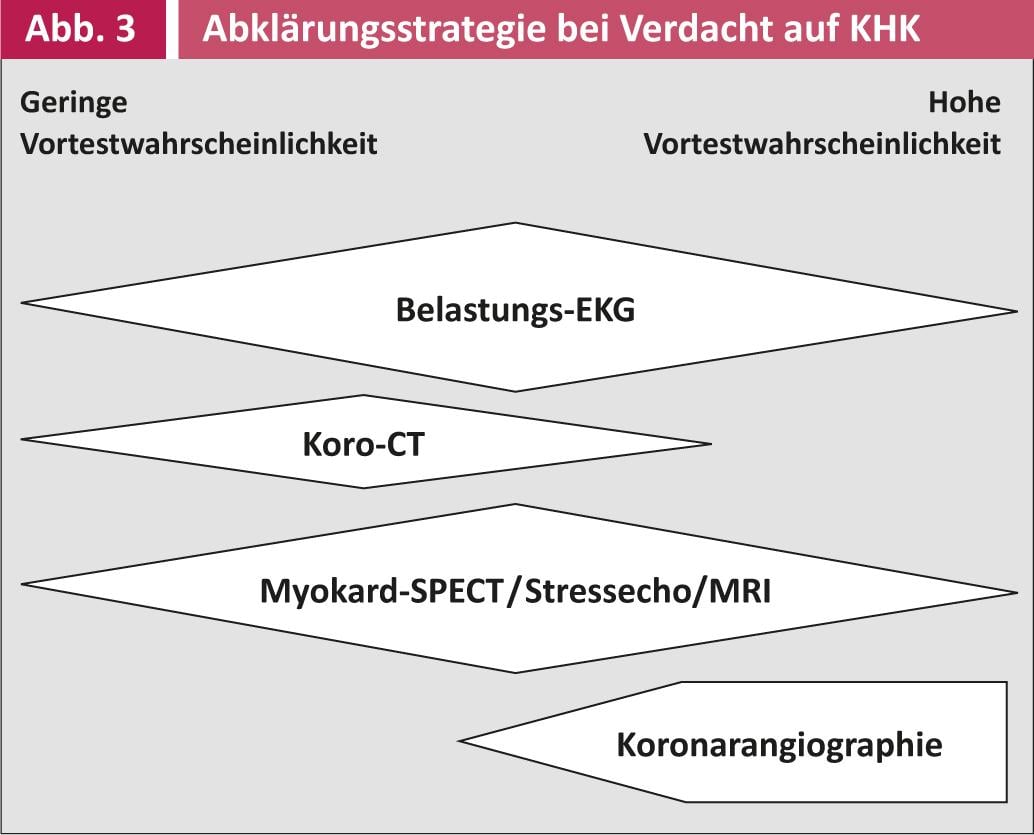

The clarification strategy for suspected coronary causes of chronic stable thoracic symptoms is mainly based on the individual determination of the pretest probability for the presence of causative coronary artery disease in the corresponding patient(Fig. 3). The value of ergometry is controversial. Even with low posttest probability (formal and subjectively unremarkable ergometry), the risk for the presence of significant coronary artery disease is still approximately 10-20% (multivessel disease 4%).

When choosing a treatment strategy, the therapeutic goal must be clearly formulated. There are prognostic indications for treatment (main stem stenoses, proximal RIVA stenoses, multivessel disease with impaired left ventricular function, or imaging evidence of a large area of ischemia) as well as purely symptomatic situations. The optimal treatment option (catheter-based revascularization, coronary bypass surgery, or drug therapy) must always be assessed on an individual basis.

Conclusion

Attentive perception of physical symptoms, targeted and prompt further medical clarification and individual risk stratification enable the best possible clarification and treatment of chest pain in a well-functioning network of general practitioners/primary care providers, specialists, emergency services and hospitals.

PD Christophe Wyss, M.D.

Literature:

- Mortality and its main causes in Switzerland, source: FSO, 29.4.2013.

- Current outcome of acute coronary syndromes. Cardiovascular Medicine 2013; 16(4): 115-122.

- ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines. European Heart Journal 2012; 33: 2569-2619.