Some gynecological diseases must be treated with antibiotics, otherwise there is a risk of secondary damage. But not every redness or itching in the genital area requires the medication. Family physicians can initiate diagnosis and in some cases treat – but should know when referral to a specialist is advisable.

The patient tells her family doctor that her vagina is burning and feels swollen. When she additionally mentions foamy discharge that smells like spoiled fish, the physician has an urgent suspicion. She takes a smear and sees unicellular parasites with tails in the light microscope – clear: the woman has a trichomonad infection. The doctor prescribes metronidazole, and after a few days the symptoms have disappeared. “Some gynecological diseases absolutely must be treated with antibiotics,” says Prof. Daniel Fink, M.D., director of the Department of Gynecology at the University Hospital of Zurich, “otherwise there can be secondary damage such as infertility, and you may infect your partner.” Family physicians can treat some of the infections themselves, Prof. Fink says, but they need to know when to call in a specialist.

Obligate pathogens must always be treated

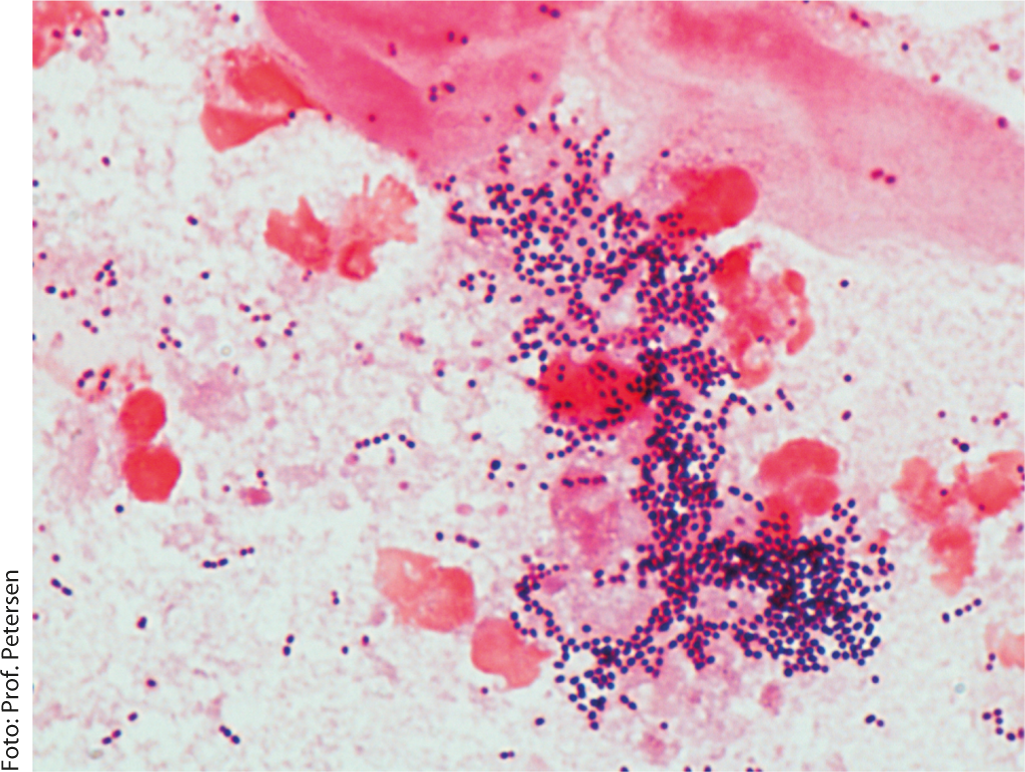

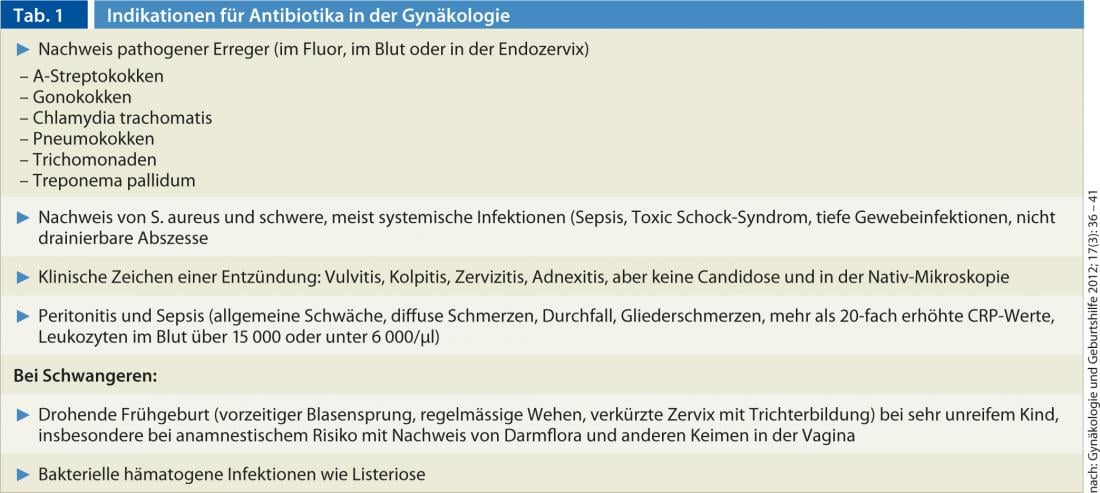

Whether a woman needs antibiotics for gynecological diseases depends, on the one hand, on the type of pathogen. On the other hand, it depends on where the germs are detected and how strongly the body reacts with inflammation. Some germs, the “real” pathogens, do not belong to the body flora and must be treated in any case. These include A streptococci (Fig. 1), pneumococci, gonococci, chlamydia, treponema, trichomonads, and listeria (Table 1). Other pathogens such as staphylococci or germs of the intestinal flora also occur in the genital area in many healthy people. They only lead to infection and require treatment if they enter normally sterile areas of the body such as the blood, peritoneum, urinary tract systems, breast, or internal genital organs, or if the woman has a defense deficiency. “The clinical condition of the patient together with the inflammatory parameters determines whether we need to prescribe antibiotics or not,” says Prof. Eiko Petersen, M.D., a gynecologist and infectious diseases specialist at the University Hospital Freiburg i.Br. If the patient has a fever, it is pretty clear that she is experiencing an infection. “It becomes difficult when the patient complains of general pain and is listless but has no fever,” says Prof. Petersen. In these cases, CRP helps. “Rising CRP levels and falling leukocyte levels in the blood indicate that the body cannot cope with the severe infection on its own,” explains Prof. Petersen. “If you don’t give antibiotics now, it can be fatal.” The drugs are indicated in any case when a woman complains of pain after childbirth or surgery, or even out of full health, and CRP is elevated more than 20-fold.

Fig. 1: A-streptococcal infection (puerperal sepsis)

Search for pathogens before therapy

Many infectious diseases in gynecology cause few or no symptoms at the beginning. For example, two-thirds of women with chlamydia infection have no symptoms. “And if the woman has symptoms, they are not always specific to a particular pathogen,” Prof. Fink says. Thus, many genital infections are accompanied by discharge, and some are accompanied by ulcers or abdominal pain. “With symptoms like that, you have to look for herpes, syphilis, and if the woman has been to Southeast Asia or Africa, ulcus molle,” Prof. Fink says. In addition to a careful history and clinical examination, the diagnosis includes a smear from the cervix and, if necessary, the urethra, as well as appropriate laboratory tests. If a sexually transmitted disease is suspected, the woman should also be advised to have an HIV test. “Many primary care physicians are familiar with swabbing and know when it is or is not appropriate to determine a serology,” Prof. Fink said. “If you’re unsure, you refer the woman to a specialist.”

Unfortunately, it happens again and again, the gynecologist says, that colleagues suspect a sexually transmitted disease and initiate empirical antibiotic therapy. “You can’t preach it often enough,” says Prof. Fink. “You have to diagnose before you treat and only prescribe antibiotics when it’s appropriate.” For example, some physicians would prescribe antibiotics if there is evidence of normal vaginal flora, or even for noninfectious skin conditions associated with redness and itching, such as lichen sclerosus. “Not only do the medications not help then, but the vaginal flora is often disturbed in the process.” If intestinal or skin germs are detected in the vagina, antibiotics are not necessary. “Unfortunately, the drugs are then often prescribed anyway,” says Prof. Petersen. Bacteriuria without evidence of inflammation also does not need to be treated with antibiotics. “I have a hard time with the recommendation that this doesn’t apply during pregnancy,” says Prof. Petersen. “I have never seen bacteriuria turn into pyelonephritis in a pregnant woman.”

Treat longer for chlamydia

If more than three leukocytes per milliliter are seen in the urine at 400-fold magnification, a urinary tract infection requiring treatment is present. Colpitis is diagnosed when three times more leukocytes than epithelia are seen in the fluorine on native microscopy, the woman complains of discomfort, and the vagina is reddened. In vaginal fluorine, small amounts of intestinal germs, i.e., less than 104 germs per milliliter of fluorine, can be detected in culture in most women and are of no significance. The most common pathogens that can be detected in the endocervix are chlamydia and gonococcus.

“Even if you’ve detected the germs in the smear, you can’t rely on that alone,” says Prof. Petersen. “For severe gynecologic infections, always include an antibiotic effective against A streptococcus, as this is the most dangerous bacterial pathogen in the genital tract.” If a pathogen cannot be detected with certainty, one goes by the pathogens usually found in genital infections. The more severe the infection without pathogen detection, the broader the spectrum of efficacy must be. Sometimes a combination of several antibiotics may also be useful if, as in the case of adnexitis, not all the pathogens in question are adequately covered by one antibiotic.

How long the woman has to take the antibiotics depends on the pathogen. For gonorrhea, for example, this is one to five days, for chlamydia two to three weeks. “That’s because the germs multiply so slowly,” explains Prof. Petersen. If the patient is well and no pathogens can be detected, the antibiotic therapy can be stopped immediately.

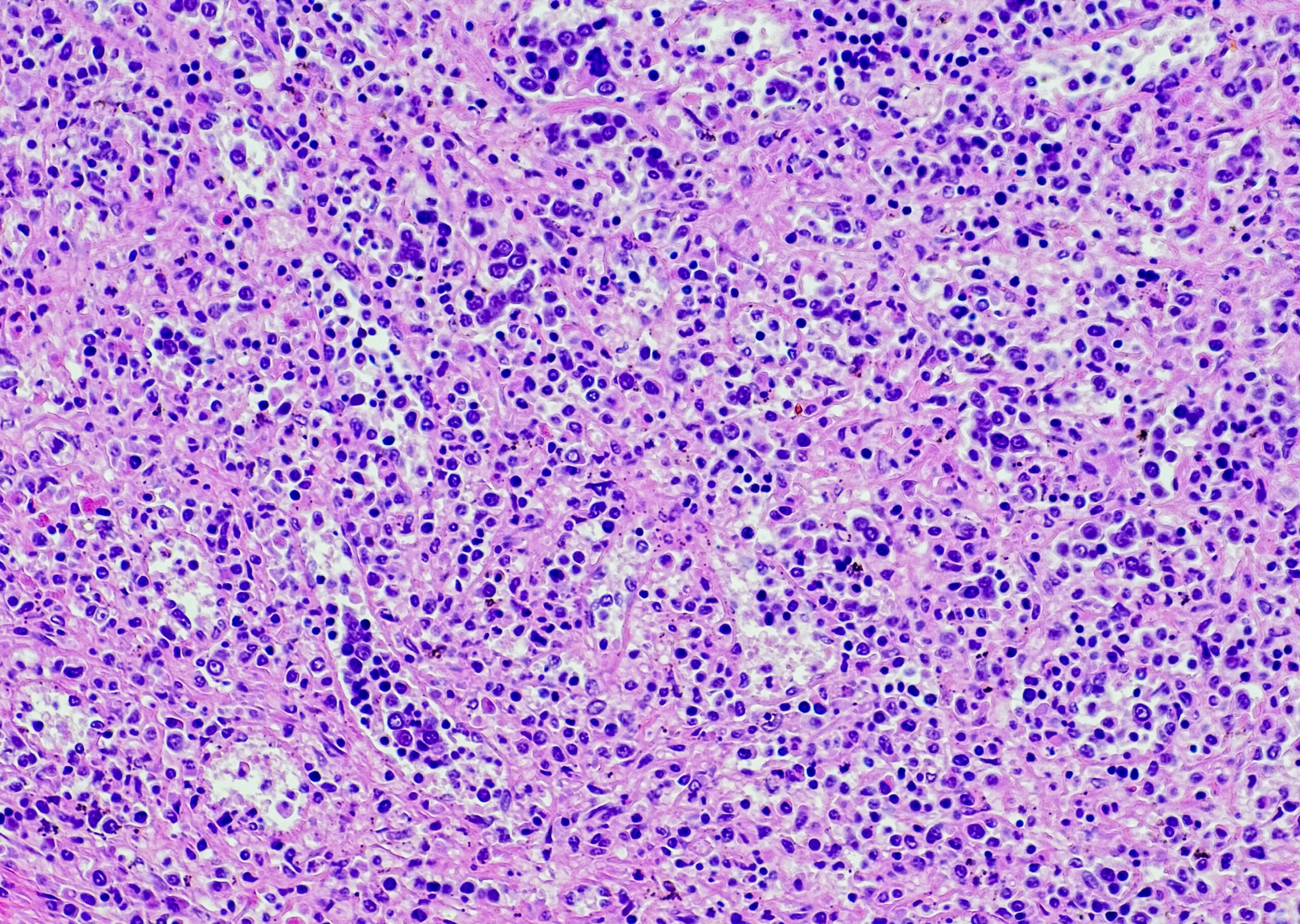

“Prescribing antibiotics without thinking can have unpleasant consequences,” says Prof. Fink. For example, the drugs disrupt the normal germ flora and can lead to an overgrowth of Clostridium difficile and subsequent diarrhea. One promotes the emergence of multi-resistant germs, some antibiotics can reduce the effectiveness of the “pill” and some trigger allergies. Frequently, fungi multiply so that a harmless fungal colonization becomes manifest candidosis (Fig. 2).

Conclusion

Used correctly, however, antibiotics make sense, not only as therapy but also as prophylaxis. For example, experts recommend a single course of antibiotics for all major procedures that involve contact with areas colonized by germs, such as hysterectomy, breast surgery or cesarean section. Antibiotic prophylaxis may also be considered for recurrent postcoital urinary tract infections after all conservative measures have been exhausted.

Sources:

Petersen E: Antibiotics in gynecologic conditions. Which therapy makes sense and when. Gynecology and Obstetrics 2012; 17(3): 36-41.