Forty years have passed since the landmark publication on the importance of Helicobacter pylori as a triggering factor for gastritis by Warren and Marshall. In that time, the understanding of associations between H. pylori infection of the gastric mucosa with both inflammatory and malignant diseases of the stomach and extragastric diseases has grown steadily. In 2022, the fourth version of the S2k guideline “Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer disease” of the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases was published. The most relevant innovations are summarized here briefly, concisely and clinically applicable.

Forty years have passed since the landmark publication on the importance of Helicobacter pylori as a triggering factor for gastritis by Warren and Marshall. During this time, the understanding of associations between H. pylori infection of the gastric mucosa with both inflammatory and malignant diseases of the stomach and extragastric diseases has grown steadily. Indications for testing and modalities of eradication therapy have been continuously developed. In parallel, current knowledge has been summarized in guidelines for the clinician. In 2022, the fourth version of the S2k guideline “Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer disease” of the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases was published [1]. This article aims to summarize the most relevant innovations in a short, concise, and clinically applicable manner.

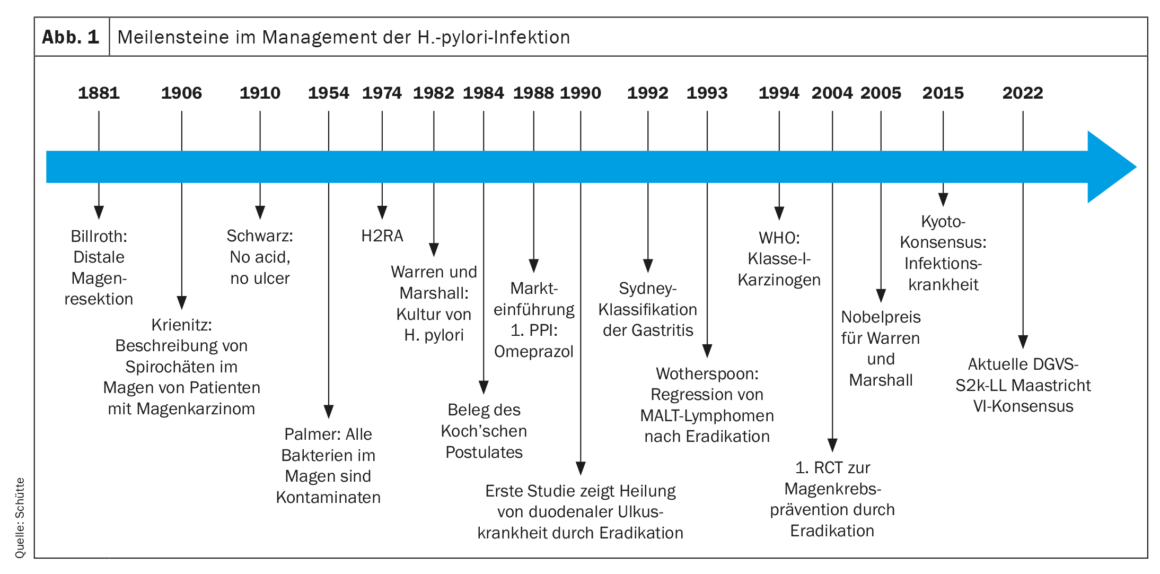

Historical development

The Halberstadt pathologist W. Krienitz had already described spirochetes in the stomach of patients with gastric carcinoma in 1906. Nevertheless, until the 1980s, peptic ulcer disease was considered a solely acid-driven disease (no acid, no ulcer, Schwarz 1910), and the bacteria discovered in the stomach by other pathologists in the following decades were considered contaminants. Finally, in 1982, Warren and Marshall succeeded in culturing H. pylori, and in self-experimentation they were subsequently able to prove the role of this bacterium in the development of gastritis by fulfilling Koch’s postulates. Finally, in the nineties of the 20th century, the first studies demonstrated the cure of duodenal ulcer disease by eradication therapy. In 1993, eradication therapy was shown to cure MALT lymphoma as well. Based on animal and clinical epidemiological data, H. pylori was first classified as a class I carcinogen by the WHO in 1994. After the indications for eradication therapy were expanded to include extragastric diseases in subsequent years, the positive effect of eradication therapy in preventing gastric cancer was demonstrated for the first time in a randomized clinical trial in 2004. Finally, the Kyoto Consensus Conference of 2015 saw another paradigm shift [2]. Since then, infection of the gastric mucosa with H. pylori has been considered an infectious disease even when infected individuals have no symptoms or complications of infection (Fig. 1). In the case of pathogen detection, this implies the indication for eradication therapy. Consequently, the indication for eradication therapy should always precede the examination for the presence of H. pylori infection. Although the prevalence of H. pylori varies significantly worldwide and is decreasing significantly, especially in industrialized nations, 30-40% of the population in Central Europe is infected, and approximately half of the population worldwide. Approximately 80% of infected individuals remain asymptomatic, although all infected individuals develop gastritis with a potential for developing complications [3].

Risk factors for ulcer disease

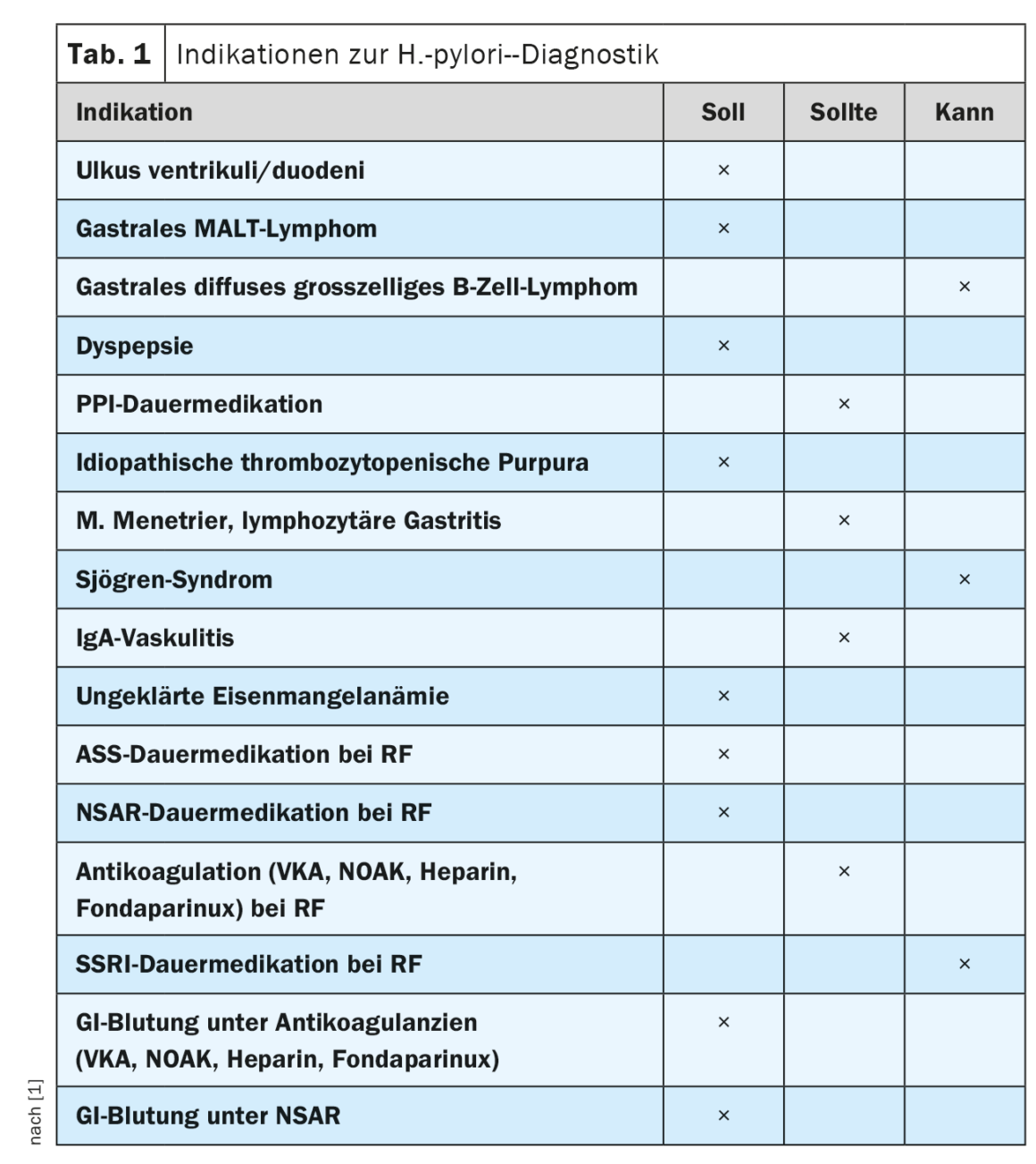

H. pylori infection of the stomach and the use of ASA or non-selective (ns) NSAIDs are the most important risk factors for the development of ventricular or duodenal ulcers [4]. Therefore, peptic ulcer ventriculi or duodeni should be tested for the presence of H. pylori infection. Eradication therapy is superior to other drug treatments for H. pylori-positive duodenal ulcers. Likewise, it effectively prevents recurrences of gastric and duodenal ulcers [5]. In addition, other non-H. pylori risk factors exist for the development of gastroduodenal ulcers or their complications. Established risk factors for the development of gastroduodenal ulcers include an age of more than 60 years, a history of ulceration, the use of nsNSAR or ASA, and severe concomitant diseases, severe psychosocial stress, and smoking. In addition, use of SSRIs, P2Y12-inhibitors, systemic steroids and anticoagulants (DOAK, VKA, heparins, selective factor X inhibitors) as well as severe concomitant diseases as risk factors for the occurrence of ulcer complications. The updated guideline recommends that when ulcer disease is present, additional, rare causes of gastroduodenal ulcer disease should be sought in the absence of H. pylori infection or ASA and/or NSAID medication. In this regard, the differential diagnosis of possible additional causes for the occurrence of gastroduodenal ulcers is broad and includes inflammatory diseases (e.g., eosinophilic gastroenteritis, Crohn’s disease, Behçet’s disease), other infections (e.g., CMV, HSV, mycobacteria, Treponema pallidum), ischemia or necrosis (e.g. after transarterial therapies such as chemo- or radioembolization) other drugs with increased risk (e.g., bisphosphonates, chemotherapy, spironolactone), neuroendocrine tumors (e.g., gastrinoma), obstruction, postoperative conditions, severe disease (e.g., ARDS or shock), or tumor infiltration, e.g., by pancreatic cancer.

Further indications for diagnostics and therapy

Due to the increased risk of ulcer disease, the updated guideline confirms the recommendation to test for the presence of H. pylori infection prior to planned long-term medication with ASA or nsNSAR in the presence of other risk factors. As a new recommendation, testing for H. pylori infection was included as part of the workup for dyspeptic symptoms. This can be done non-invasively in patients younger than 50 years with no alarm symptoms such as weight loss, dysphagia or bleeding signs. The rationale for this is that elimination of H. pylori infection in patients with prolonged dyspeptic symptoms and negative endoscopic findings results in sustained symptom improvement in up to 10% of cases. However, in patients beyond the age of 50 or in the presence of alarm symptoms, esophagogastroduodenoscopy is indicated to rule out organic dyspepsia, especially malignancy [6].

Also included as a new recommendation was testing for H. pylori in patients with planned or ongoing long-term PPI therapy. This is because atrophic changes in the gastric corpus mucosa and corpus-dominant H. pylori gastritis may develop during long-term PPI therapy. In H. pylori-positive patients, increased progression of preexisting inflammatory changes has been observed with PPI continuous therapy. In addition, synergistic effects of PPI therapy and H. pylori infection result in the increased presence of non-H. pylori germs in the gastric mucosa. It is postulated that these factors increase the risk of gastric carcinoma occurrence. The current guideline indications for testing for H. pylori are summarized in Table 1.

H. pylori infection of the gastric mucosa is the most important risk factor for the development of gastric carcinoma, causing more than one-third of infection-driven malignancies. About 90% of non-cardia gastric carcinomas are associated with H. pylori infection [7]. In this regard, gastric carcinomas develop through a multistep process that progresses from H. pylori-induced gastritis to multifocal atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and finally dysplasia to carcinoma (Correa cascade). International guidelines therefore recommend endoscopic surveillance of patients with high-risk lesions (MAPS guidelines [8]). However, a screen-and-treat strategy has been shown to be cost-effective only in regions of the world with high H. pylori prevalence and intermediate or high gastric carcinoma incidence [9]. These conditions do not apply to Central Europe. Nevertheless, there are at-risk populations for which screening for the presence of H. pylori infection is indicated. Only recently, a prospective randomized clinical trial including H. pylori positive first-degree relatives of patients with gastric cancer confirmed that successful eradication therapy reduces the risk of gastric cancer by 73%. [10]. Eradication therapy is equally effective in preventing metachronous carcinoma in patients who have received curative therapy for gastric carcinoma in the past by partial gastric resection or endoscopic procedures. Successful eradication therapy reduces the risk of metachronous gastric cancer by 50% in a recent prospective randomized clinical trial [11]. Therefore, a new recommendation was included in the updated guideline to perform H. pylori testing in all individuals at increased risk for gastric cancer, which should be offered primarily by endoscopic biopsy from the age of approximately 40 years. This screen-and-treat strategy is intended to reach as a risk population first-degree relatives of patients with gastric cancer, persons born and/or raised in H. pylori high-prevalence areas and high-incidence areas for gastric cancer (Asia, Eastern Europe, Central and South America), patients with advanced atrophic gastritis with or without intestinal metaplasia, and patients with previous gastric neoplasia.

How to diagnose?

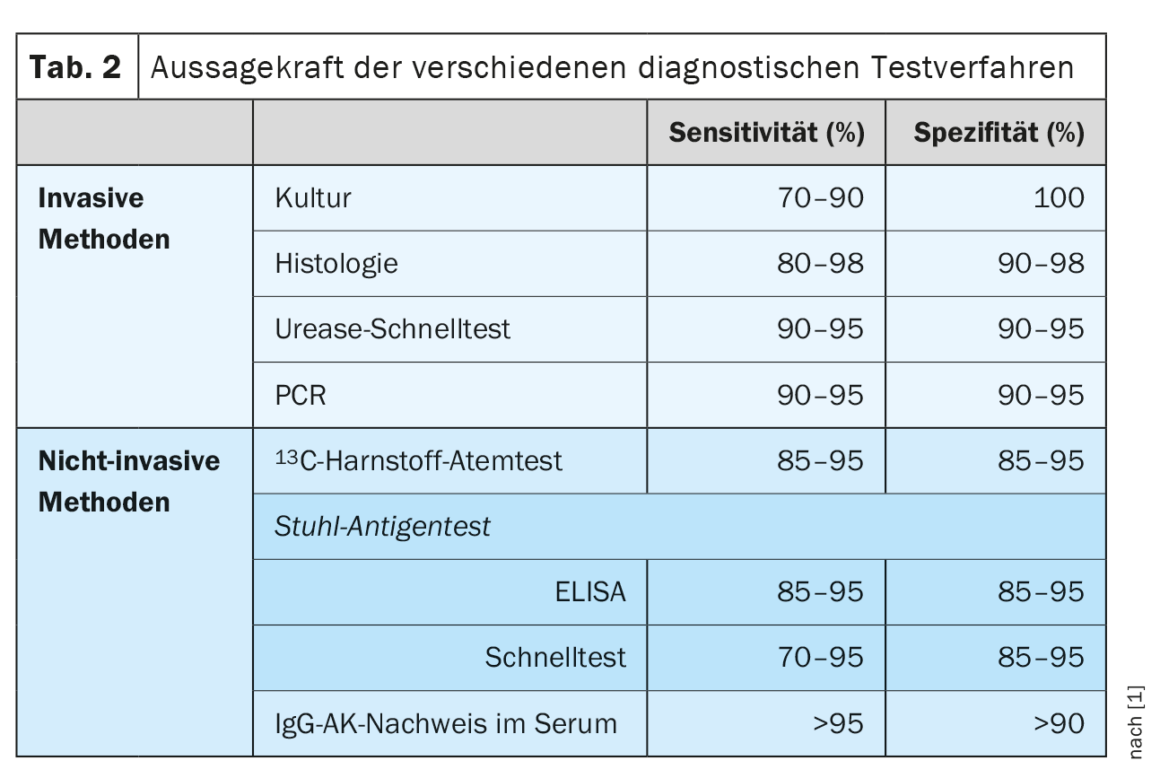

To test for the presence of H. pylori infection, invasive (histology, rapid urease test, culture, PCR) and noninvasive (13C-urease breath test, antigen detection in stool, IgG antibodies in serum) are available. No single method is absolutely accurate, and the risk of false positive results increases with decreasing prevalence of H. pylori infection in industrialized countries. (Tab. 2). Previous guidelines therefore called for detection of H. pylori infection by two testing procedures. The updated guideline now defines special situations that make a second positive test unnecessary. Histological detection of H. pylori in combination with chronic active gastritis is nearly 100% specific. Similarly, due to the high prevalence of H. pylori in the presence of duodenal ulcer, a positive test result is sufficient to diagnose H. pylori infection. A positive H. pylori culture from gastric biopsies is 100% specific on its own and is sufficient to indicate eradication therapy. However, knowledge of limitations of the test methods is relevant. For example, serological testing for IgG antibodies to H. pylori cannot distinguish between an active infection and one that has occurred, and therefore has any value at all only in exceptional clinical situations. Similarly, conditions that result in decreased bacterial density (e.g., PPI therapy, ingestion of H. pylori active antibiotics, mucosal atrophy, hypochlorhydria, and acute upper GI bleeding) result in decreased test sensitivity. Therefore, for reliable H. pylori diagnosis, it is recommended that a two-week interval from PPI therapy and a four-week interval from previous eradication or other antibiotic therapy be observed prior to testing.

How to treat?

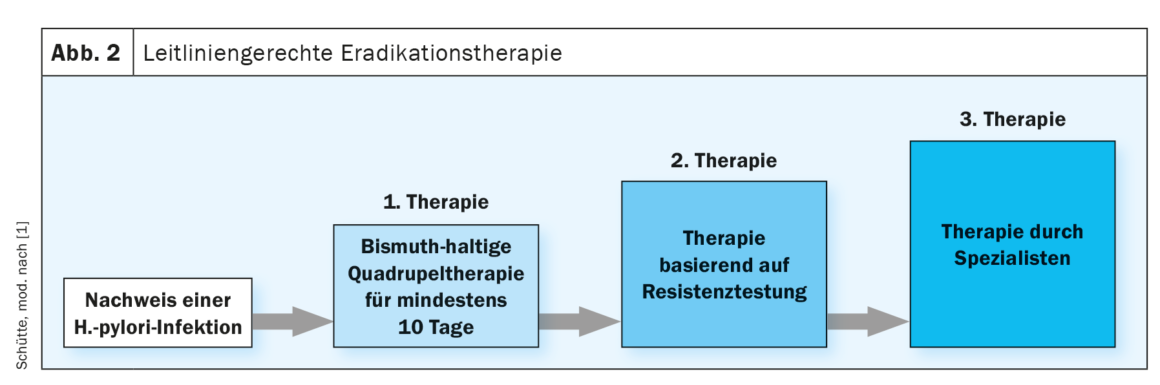

Since the 1990s, PPI triple therapy, initially for seven days, since 2010 over 14 days, was considered the established standard therapy for H. pylori eradication. Increasing resistance to the antibiotics used in triple therapies, especially clarithromycin, metronidazole, and quinolones, already had an impact on therapeutic recommendations in the last guideline. Here, knowledge of the local clarithromycin resistance rate was assumed as a stratum for the selection of first-line eradication therapy. The further increasing resistance rates as well as the lack of clinical data on the local resistance situation now led to a relevant change in the therapeutic recommendations in the updated guideline. Thus, the bismuth-containing quadruple therapy is now recommended for at least ten days as empirical first-line therapy. At the latest from the second line onwards, susceptibility-controlled eradication therapy should be used, which therefore requires resistance testing. (Fig. 2). Newly emphasized in the guideline update is the reliable bioptic exclusion of gastric carcinoma in the presence of a ventricular ulcer by endoscopic healing control after 6-8 weeks. Similarly, the guideline reinforces the recommendation to monitor eradication success, which can be done by 13C-urea breath testor stool antigen test, unless there is an indication for control EGD.

Prevention of ulcer disease by PPI therapy in high-risk constellations.

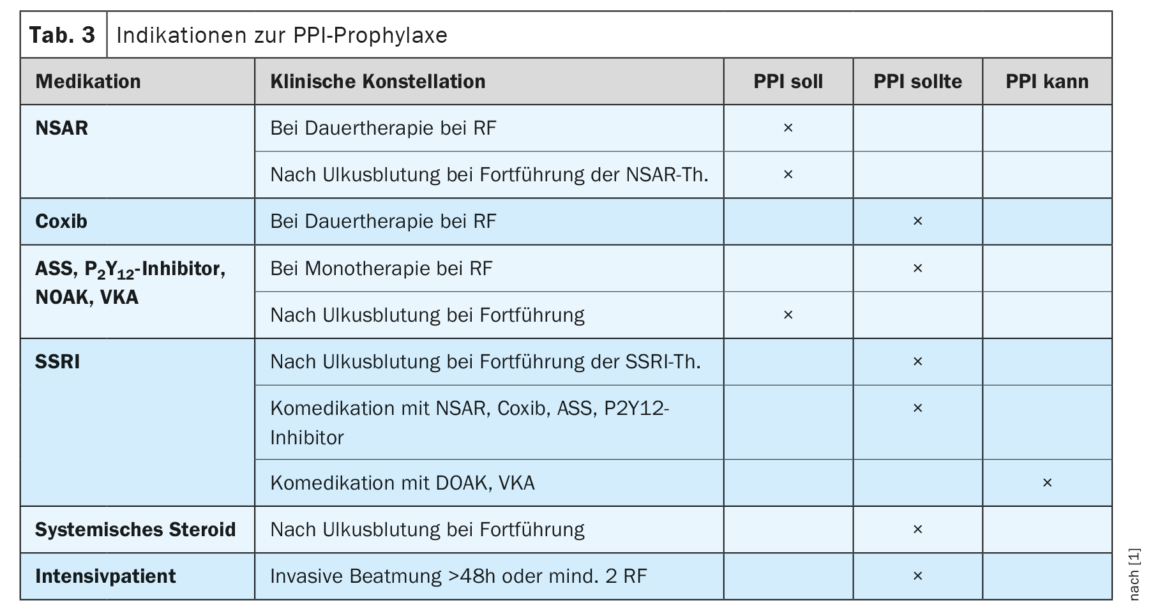

In selected clinical situations, there is an indication for continuous PPI therapy to prevent the occurrence of ulcers or ulcer complications. The updated guideline now concretizes these recommendations (Tab. 3) . In this context, the individual risk assessment for each patient depending on his or her risk profile is of crucial importance. Although age greater than 60 years has been documented as a risk factor, this alone is not sufficient as an indication for PPI prophylaxis. Rather, other factors must be added to justify one. A target recommendation for PPI prophylaxis is made for patients who have already experienced an ulcer complication while on NSAIDs, ASA, P2Y12inhibitor, or other anticoagulation. Similarly, if other risk factors are present, PPI prophylaxis should be given to patients on continuous NSAID therapy. Patients taking two anticoagulants should be treated prophylactically with a PPI. Less strong recommendations are made for other risk constellations. These include long-term therapy with a coxib in the presence of clinical risk factors; long-term therapy with an ASA, P2Y12inhibitor, NOAK, or vitamin K antagonist in the presence of additional risk factors; long-term use of an SSRI after ulcer complication or in co-medication with NSAIDs, coxib, ASA, or P2Y12inhibitor. Similarly, patients who have experienced a complicated ulcer while on systemic steroid therapy and require continuation of steroid therapy should receive a PPI prophylactically. For patients in the ICU, prophylactic treatment with a PPI should be given if invasive ventilation is used for more than 48 hours or if at least two other risk factors are present (stay > one week, sepsis, ARDS, hepatic or renal failure, polytrauma, burn, high-dose steroid therapy).

Summary

The updated German guidelines on H. pylori infection and ulcer disease follow international guidelines and now evaluate infection of the gastric mucosa with H. pylori as an infectious disease, even without the presence of symptoms or complications [2,12]. This represents a decisive paradigm shift. The detection of an H. pylori infection implies an indication for therapy. Formally, there are no contraindications against therapy. The lack of conviction for the necessity of eradication therapy should now be weighed before diagnosis. In addition to a screen-and-treat strategy to prevent gastric cancer for patients at increased risk for developing it, a tough recommendation is made to test for H. pylori for certain patient populations to prevent ulcer or ulcer complication. Similarly, extragastric conditions such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura or unexplained iron deficiency anemia indicate testing for H. pylori.

In consequence of increasing rates of resistance to antibiotic groups used in eradication therapy and insufficient nationwide epidemiological data on the local resistance situation, the guideline emphasizes the need for susceptibility-controlled treatment from the second line at the latest. Recognizing the high rate of clarithromycin resistance, first-line therapy should be bismuth-based quadruple therapy for at least ten days. Regardless of H. pylori infection, selected patient populations benefit from prophylactic PPI therapy to prevent ulcers or ulcer complications. Here, the individual assessment of the risk profile of the individual patient remains crucial.

Take-Home Messages

- Infection of the stomach with Helicobacter pylori is an infectious disease, even without symptoms or complications.

- Detection of infection indicates eradication therapy.

- For patients with an increased risk of gastric carcinoma, should

be offered a screen-and-treat strategy. - Empirical eradication therapy should be administered in the first line with

Bismuth-based quadruple therapy can be used. - Only in certain risk constellations is prophylactic PPI-

therapy to prevent ulcer disease is useful.

Literature:

- Updated S2k guideline Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal ulcer disease of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) 2022. AWMF register number: 021-001. Z Gastroenterol 2023; 61(5): 544-606.

- Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, et al: Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut 2015; 64(9): 1353-1367.

- Malfertheiner P, Camargo MC, El-Omar E, et al: Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023; 9(1): 19.

- Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Hunt RH: Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peptic-ulcer disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2002; 359(9300): 14-22.

- Ford AC, Gurusamy KS, Delaney B, et al: Eradication therapy for peptic ulcer disease in Helicobacter pylori-positive people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 4(4): CD003840.

- Koletzko L, Macke L, Schulz C, Malfertheiner P: Helicobacter pylori eradication in dyspepsia: New evidence for symptomatic benefit. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2019; 40-41: 101637.

- Plummer M, de Martel C, Vignat J, et al: Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016; 4(9): e609-e616.

- Pimentel-Nunes P, Libanio D, Marcos-Pinto R, et al: Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy 2019; 51(4): 365-388.

- Lee YC, Lin JT, Wu HM, et al: Cost-effectiveness analysis between primary and secondary preventive strategies for gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007; 16(5): 875-885.

- Choi IJ, Kim CG, Lee JY, et al: Family history of gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori treatment. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(5): 427-436.

- Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, et al: Helicobacter pylori therapy for the prevention of metachronous gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(12): 1085-1095.

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, et al: Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut 2022; doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327745.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(5): 4-8