According to current knowledge, gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis are distinct entities that require different therapeutic approaches. This is particularly emphasized in the updated S2k guideline “Gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis” published this year by the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) are the most common diseases of the esophagus and show partly overlapping symptoms [1]. There is no diagnostic gold standard that can prove or rule out GERD. Instead, criteria have been developed by which it is possible to narrow down the diagnostic probability. The Lyon Consensus is leading the way. This is based on both endoscopic and functional diagnostic findings. Especially in refractory reflux patients, a possible EoE should always be considered in the differential diagnosis, as emphasized in the guideline.

GERD vs. EoE

While GERD is an inflammatory disease of the esophagus (stomach) triggered by pathologic reflux of gastric contents, EoE is a chronic, immune-mediated disease of the esophagus characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation. Other systemic and/ or local causes of esophageal eosinophilia should be excluded [3]. If EoE is left untreated, there is a high risk of esophageal fibrosis, strictures, and bolus obstruction [4–6].

Endoscopic findings in EoE usually conspicuous

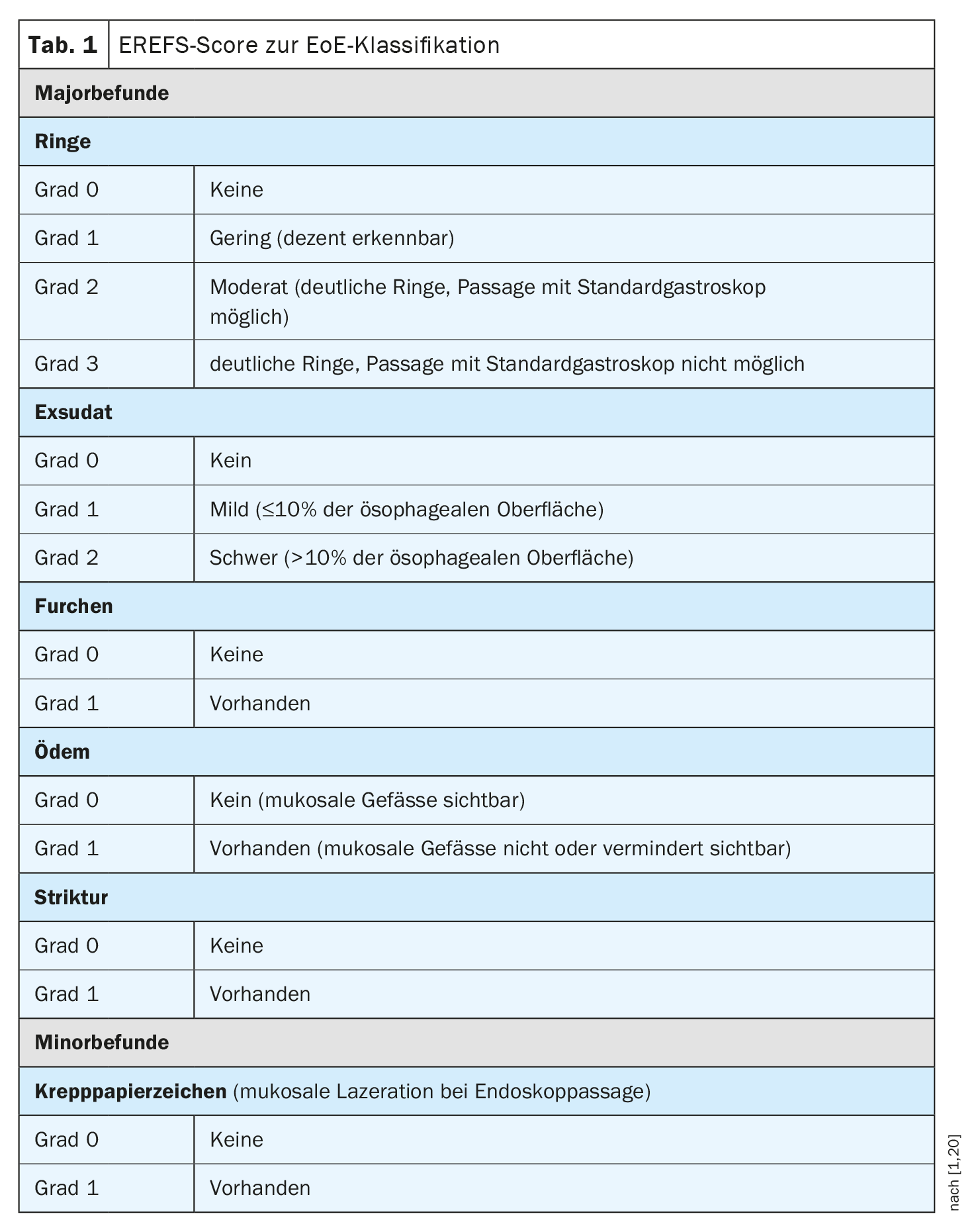

If symptoms initially interpreted as GERD do not improve with 8 weeks of PPI therapy, endoscopic examination is indicated. In GERD patients, approximately 70% of endoscopies are unremarkable [2]. In contrast, characteristic endoscopic abnormalities are detected in approximately 90% of EoE patients. These include visible structural changes of the esophagus in the form of whitish exudates, longitudinal furrows, mucosal edema, fixed rings, a small-caliber esophagus and strictures, and mucosal laceration on endoscopic massage (crepe paper sign). These features may occur alone or in combination. The Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS) (Table 1) should be used for endoscopic reporting of EoE [1]. This is a classification system by which histological features can be systematically documented and classified. This scoring system has been shown to correlate with histologic improvement in EoE [24].

Diagnostic latency: prognostically unfavorable

In a retrospective study of 200 patients in the Swiss EoE cohort, it was shown that with increasing latency of diagnosis, the rate of esophageal strictures on index endoscopy increases [4]. If the diagnosis was made within two years of symptom onset, esophageal stenosis was found in 47% of cases. If the diagnosis was made after more than 20 years since symptom onset, the stricture rate increased to 88%. In the largest cohort study to date of 721 patients (including 117 children) conducted in the Netherlands, the rate of endoscopic fibrosis signs at diagnosis was found to be significantly higher in adults (76%) than children (39%) [5]. If the time to diagnosis was a maximum of two years, the rate of fibrosis signs on index endoscopy was 54%. The rates of high-grade strictures and bolus obstruction were 19% and 24%, respectively. With a diagnostic delay of 21 years or longer, these rates increased to 52% and 57%, respectively. Based on these data, a risk of progression of 9% per year of untreated disease was calculated [5].

Recommended therapeutic strategies for EoE

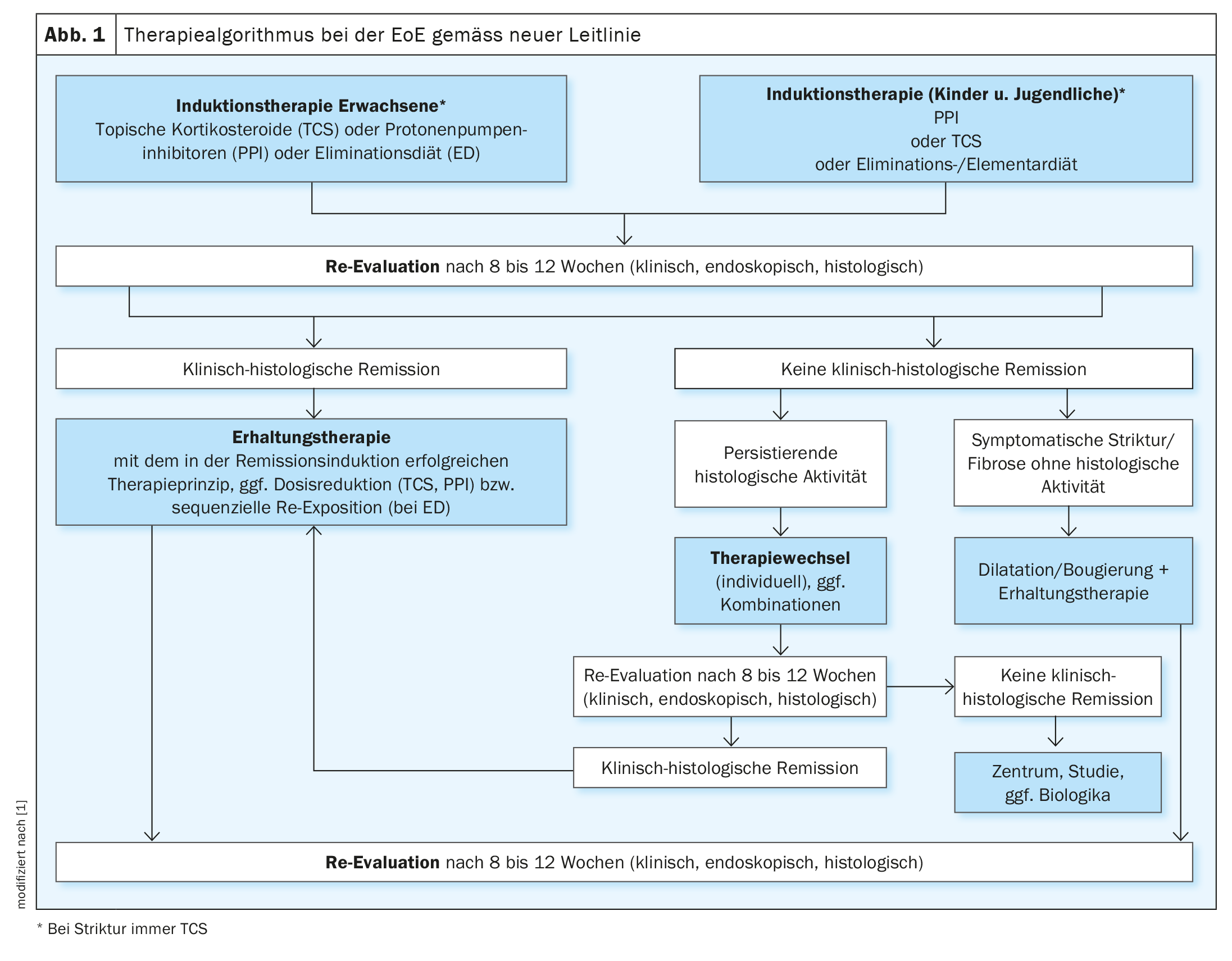

Current European and US guidelines advise that if active EoE is detected, induction therapy should be initiated with the goal of achieving clinical histologic remission (Fig. 1) [1,3,7]. In adults, therapy with topical corticosteroids is recommended. Alternative treatment options include high-dose PPI or a 6-food elimination diet. In the DGVS guideline, the current evidence regarding these therapeutic options is presented in detail, including the following study findings [1]:

- Topical corticosteroids: To date, 11 placebo-controlled double-blind studies are available on remission-inducing therapy of EoE with topical corticosteroids in adults and children, seven of them with budesonide and four with fluticasone [1]. In addition, five randomized trials with other comparators exist: Fluticasone vs. prednisolone, fluticasone vs. esomeprazole, budesonide suspension vs. budesonide nebulizer, budesonide suspension vs. fluticasone nebulizer [1]. In addition, 6 meta-analyses are available [8–13].

- High-dose PPI: In a prospective observational study published in 2016, a clinico-histological remission rate of 33% was reported in 121 adult patients with active EoE after 8 weeks of high-dose PPI therapy (omeprazole 2× 40 mg daily) [14]. In a prospective registry study published in 2020, interim analysis of 630 patients (554 adults) after PPI therapy showed histologic remission rates of 48.8% (<15 eos/hpf) and 37.9% (<5 eos/hpf), respectively [15].

- Elimination diet: the 6-food elimination diet eliminates the foods most commonly associated with food allergies, i.e. cow’s milk proteins, wheat, soy, egg, nuts and fish/seafood. In a retrospective study in children, it was shown that up to 74% of the patients treated in this way showed histological remission, but when the individual foods were reintroduced by means of renewed endoscopies, the respective triggering food could only be identified in a few patients [16,17].

The goal of successful induction therapy is both clinical histologic remission and improvement of endoscopic findings. After 8 to 12 weeks, an appropriate control should be performed [1].

- Validated questionnaires (e.g., ESAI-PRO, DRQ for adults, PEES2 for children) or a numerical scale are useful for objective assessment of symptoms [21–23].

- Endoscopic findings should be recorded in a standardized manner using the EREFS classification [20].

- Currently, only endoscopy with biopsy is suitable for verifying the presence of histologic remission, because symptoms and endoscopic findings often correlate poorly with inflammatory activity [1].

- To date, no reliable non-invasive biomarkers exist either [1].

After induction therapy or remission: maintenance therapy

In EoE patients, remission-maintaining therapy should be continued after clinico-histological remission has been achieved (Fig. 1). The guideline recommends that their effectiveness be reviewed clinically and endoscopically-histologically every 1-2 years.

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 28 patients published in 2011, remission-maintaining therapy with budesonide suspension 2× 0.25 mg daily resulted in a significantly lower rate of histologic recurrence after 50 weeks. The rate of histologic remission at 50 weeks was 36% with budesonide and 0% with placebo. AlsoRate of clinical remission was higher at 50 weeks compared with placebo, but not statistically significant [18].

A European phase III study of 204 adult EoE patients in clinical histological remission demonstrated the efficacy and safety of orodispersible budesonide tablet in remission maintenance [19]. In this randomized double-blind study, the primary endpoint of clinical histologic remission was achieved after 48 weeks of therapy with budesonide orodispersible tablet at the daily dose of 2× 0.5 mg or 2× 1 mg in 73.5% and 75% of patients, respectively (p<0.0001 vs. placebo: 4.4%).

The guideline mentions that there are no RCTs to date on long-term PPI therapy for EoE and few data on long-term effects of an elimination diet.

Literature:

- S2k guideline Gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) – March 2023 – AWMF register number: 021-013. Z Gastroenterol 2023; 61(7): 862-933.

- Gerson LB: Diagnostic Yield of Upper Endoscopy in Treated GERD Patients. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 1408-1409.

- Lucendo AJ, et al: Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European Gastroenterology Journal 2017; 5: 335-358.

- Schoepfer AM, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 1230-1236.e1-2.

- Warners MJ, et al: The natural course of eosinophilic esophagitis and long-term consequences of undiagnosed disease in a large cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113: 836-844.

- Shaheen NJ, et al: Natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review of epidemiology and disease course. Dis Esophagus 2018; 31(8): doy015. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy015.

- Hirano I, et al: AGA Institute and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1776-1786.

- Chuang M-y, et al: Topical SteroidTherapy for the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 2015; 6: e82.

- Tan ND, Xiao YL, Chen MH: Steroids therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J of Digestive Diseases 2015; 16: 431-442.

- Lipka S, et al: Systematic review with network meta-analysis: comparative effectiveness of topical steroids vs. PPIs for the treatment of the spectrum of eosinophilic esophagitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2016; 43: 663-673.

- Murali AR, et al: Topical steroids in eosinophilic esophagitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2016; 31: 1111-1119.

- Rokkas T, Niv Y, Malfertheiner P: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials on the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults and Children. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2020; 55: 400-410.

- de Heer J, et al: Histologic and Clinical Effects of Different Topical Corticosteroids for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Lessons from an Updated Meta-Analysis of Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trials. Digestion 2020; 102: 377-385.

- Gómez-Torrijos E, et al: The efficacy of step-down therapy in adult patients with proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2016; 43: 534-540.

- Laserna-Mendieta EJ, et al: Efficacy of proton pump inhibitor therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in 630 patients: results from the EoE connect registry. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2020; 52: 798-807.

- Kagalwalla AF, et al: Identification of Specific Foods Responsible for Inflammation in Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis Successfully Treated With Empiric Elimination Diet. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition 2011; 53: 145-149.

- Kagalwalla AF, et al: Effect of Six-Food Elimination Diet on Clinical and Histologic Outcomes in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2006; 4: 1097-1102.

- Straumann A, et al: Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 400-409.e1

- Straumann A, et al: Budesonide Orodispersible Tablets Maintain Remission in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2020; 159: 1672-1685.e5

- Hirano I, et al: Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut 2013; 62: 489-495.

- Schoepfer AM, et al: Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2014; 147: 1255-1266.e21

- Dellon ES, et al: Development and field testing of a novel patient-reported outcome measure of dysphagia in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 38: 634-642.

- Martin LJ, et al: Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis Symptom Scores (PEESS v2.0) identify histologic and molecular correlates of the key clinical features of disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 135: 1519-1528.e8

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023, 18(9): 34-36