COPD is considered a preventable and treatable disease, but this is only partially true. Cigarette smoking is the most commonly identified and preventable risk factor in this country – but in many patient cohorts, including Switzerland, one-third or even more are nonsmokers [1]. Occupational and environmental factors may play a role. The diagnosis of COPD is based on airway obstruction, defined as a ratio (after bronchodilation with medication) of FEV1/FVC below 0.7 [2]. Although this cut-off has been questioned and age-dependent lower limits have been propagated instead (LLN, “lower limits of normal”), this continues to be valid. The following article provides an update on the diagnosis and treatment of COPD.

It is believed that 330 million people worldwide are affected by COPD and only a quarter of them have been diagnosed. By 2020, epidemiologists expect COPD to be the third leading cause of death in Western countries [3]. A global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD can also be found in the GOLD Executive Summary [4].

Diagnosis and assessment

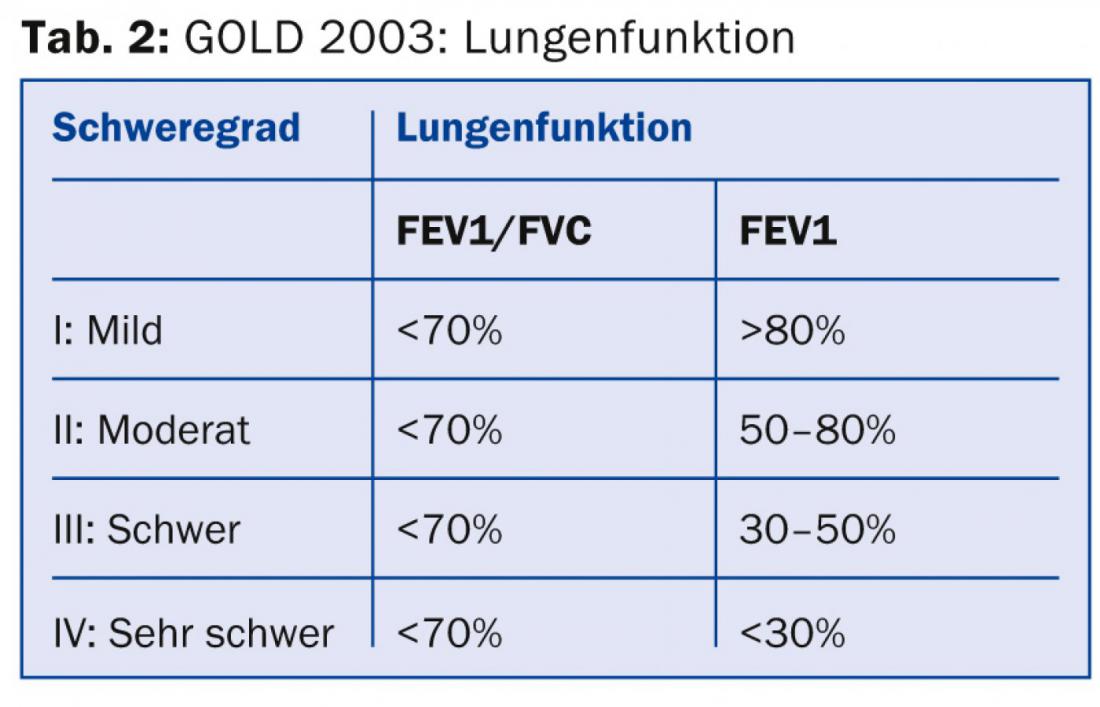

History, clinic and practice spirometry: typical symptoms are dyspnea, chronic cough and sputum production. It is often recommended that practice spirometry be performed in patients over 40 years of age at increased risk with or without symptoms [5]. This is simple and allows COPD to be diagnosed and classified into severity levels I-IV (mild, moderate, severe, and very severe), as recommended by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) committee in the first Consensus Report in 2001. To date, there is no basis for general screening.

The current GOLD strategy: in subsequent years, airway obstruction was found to have limited correlation with various patient health problems and outcomes, and a more comprehensive approach to capture different phenotypes became necessary [6].

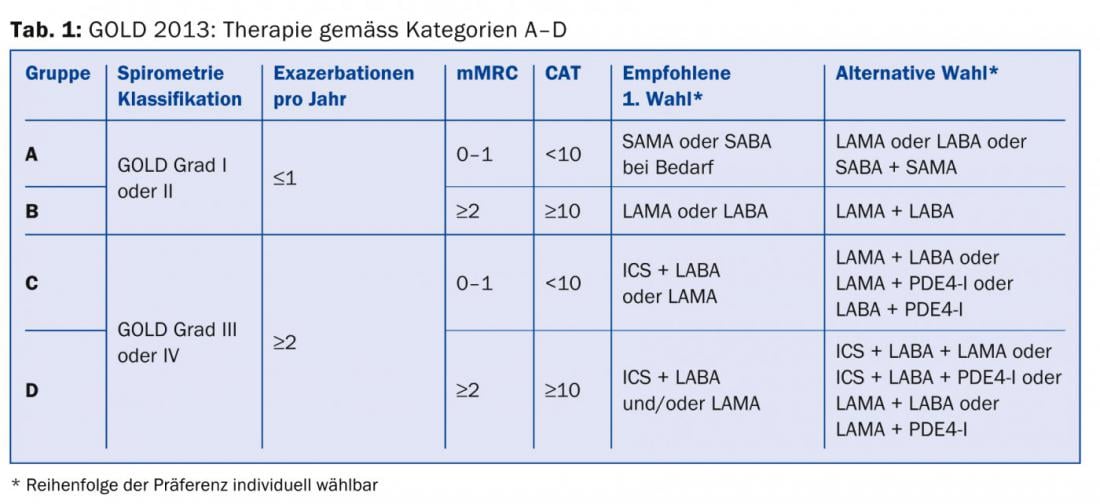

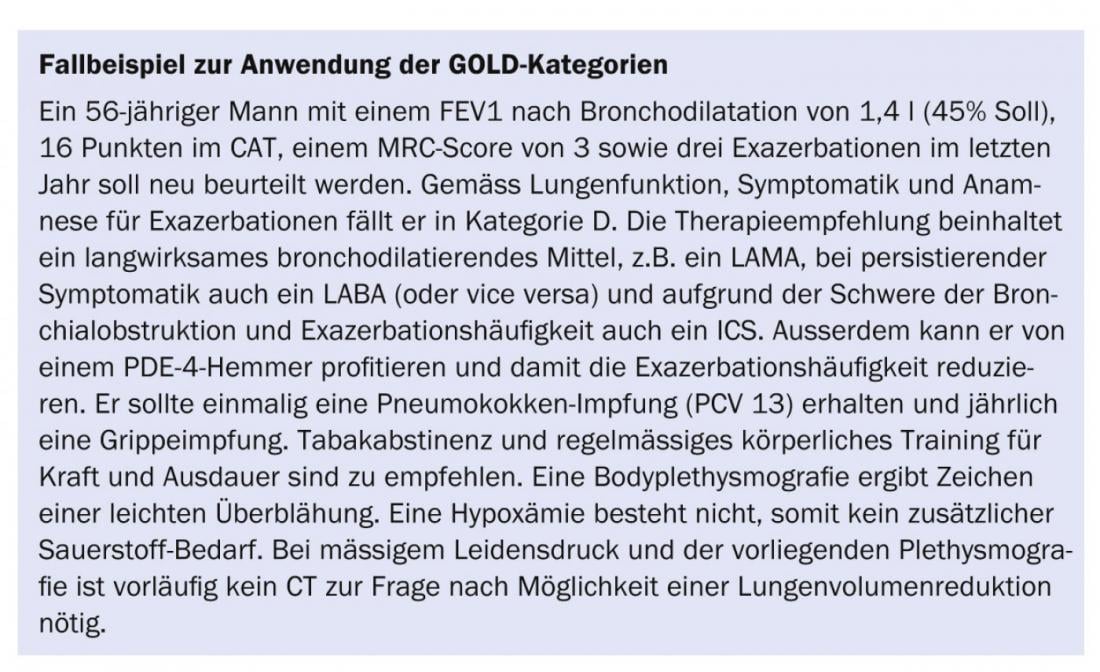

Although a completely new orientation of a classification system that has only been valid for a few years is not easy to communicate, the categorization into four risk groups (A, B, C, D) also shows clear advantages: The classification is still based on the severity of the obstruction, but the severity of the symptoms and the frequency of exacerbations are now also taken into account. Thus, the lowest mortality rate is found in category A, the highest in category D, and a comparable rate in categories B and C. This is also true for the frequency of hospitalizations, but exacerbations increase continuously from A-D. Comorbidities are (unsurprisingly) more often found in the more symptomatic categories B and D. Even this current classification will not be perfect, as COPD patients manifest themselves too heterogeneously, for example with or without concomitant emphysema, with different patterns of inflammation, disturbances in gas exchange, radiologically detectable additional findings and much more [2].

Although the recently published Swiss guidelines have not adopted this new classification [7], at least as a pulmonologist one will not be able to avoid it here.

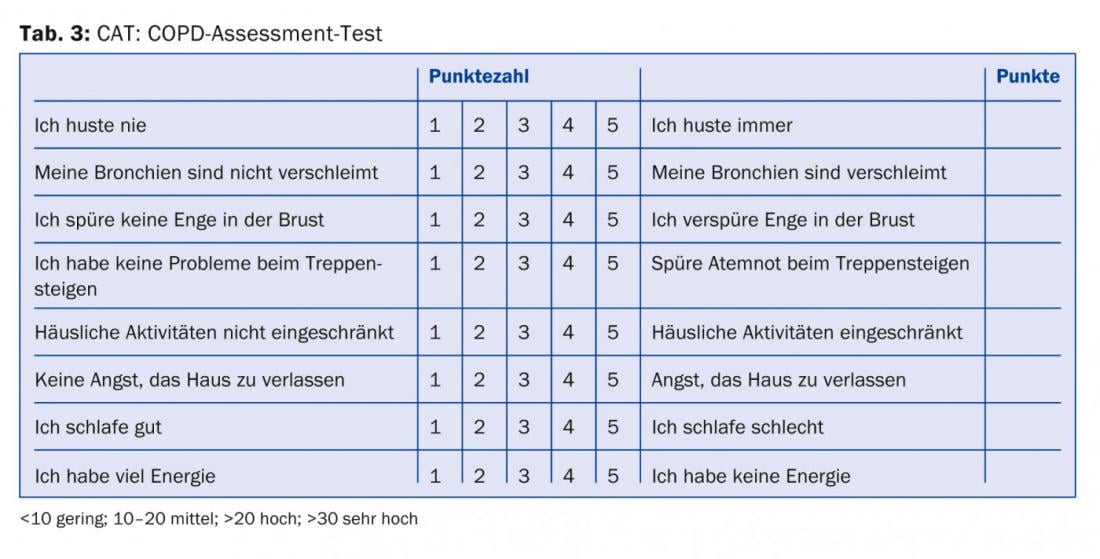

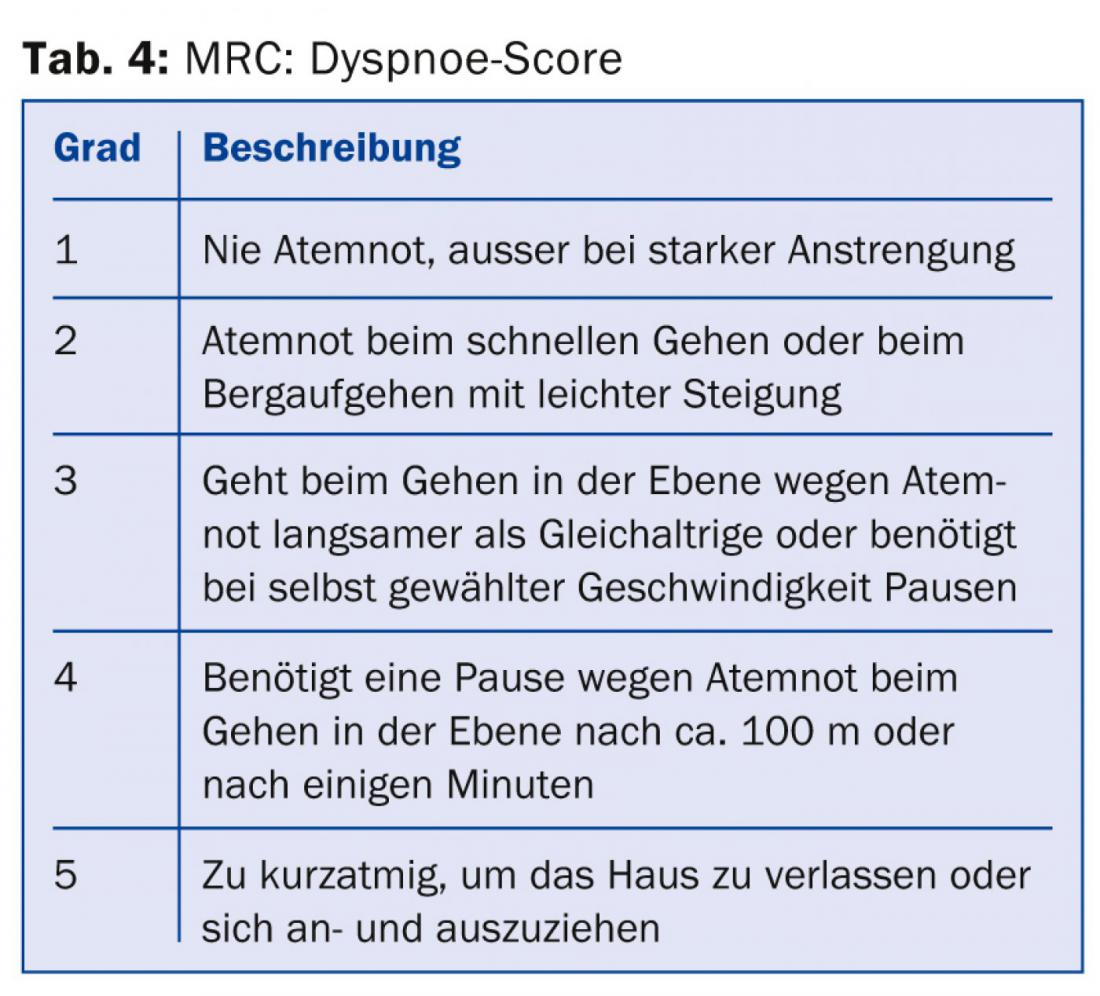

All physicians treating COPD patients should at least be aware that, in addition to the severity of airway obstruction, symptom severity and exacerbation frequency [8] should be included in the risk stratification and treatment plan. The necessary information for categorization and therapy recommendation (Tab. 1) can be collected from lung function (Tab. 2), CAT score (Tab. 3), dyspnea score (Tab. 4) and history regarding exacerbations.

Experience shows that patients are often not treated according to the guidelines [9]. This may be for individual reasons, and often recommendations are published before their superiority over a previous practice has been proven. However, cost savings and perhaps avoidance of side effects may be expected with guideline-compliant treatment. Polypragmatic treatments and a “conceptless” use of all possible drugs, sometimes with several substances of the same drug groups, reflect on the one hand only a limited effect and persistent symptoms despite treatment, but on the other hand also an insufficiently clearly determined management of the patient by the physician.

Therapeutic options

Most treatment options are not life-prolonging and have little or no effect on disease progression. Nevertheless, the interest of pharmaceutical companies in this disease is high, probably also due to immense patient numbers and a large number of undiagnosed cases. Several new drugs and combinations are currently being launched or are about to be launched. However, a fundamental change in the severity and prognosis of COPD is not immediately expected as a result; rather, gradual differences in the onset of action, the strength of action, and improvement in additional endpoints such as endurance performance or “trough FEV1” (first-second capacity at the end of the dosing interval) are mentioned. But the user-friendliness of the inhalation devices is also being continuously improved. For their part, advocates of longer marketed compounds highlight data with large case numbers on treatment safety and proven clinical benefit.

Drug therapies

Bronchodilators and inhalable steroids: long-acting bronchodilators (long-acting beta-agonists [LABA] and long-acting antimuscarinic agonists [LAMA]) are the mainstay of drug treatment. Although this only slightly improves first-second capacity, the decrease in hyperinflation, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects still result in a decrease in dyspnea, symptom improvement, prevention of exacerbations, improvement in quality of life, and decreased need for “rescue” medications [10,11]. The combined use of LABA/LAMA and topical inhaled steroids (ICS) is recommended in patients with frequent exacerbations and/or with a severity of bronchial obstruction GOLD III or greater. In practice, ICS are prescribed too frequently [12]. The prevention of exacerbations is offset by a previously underestimated increase in pneumonia due to ICS use [13].

Other anti-inflammatory therapies: The commonly prescribed N-acetylcysteine probably has no therapeutic or prognostic effect in COPD therapy. A new effective substance is the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor roflumilast. This substance can be used to prevent exacerbations predominantly in patients with a “bronchitic phenotype” [14]. However, only moderately severe exacerbations appear to be significantly prevented, and benefits in terms of quality of life and mortality have not yet been demonstrated.

Other treatment options

Rehabilitation: Patients with COPD generally benefit from physical exercise. Medical training therapy (MTT) program offerings can be found at www.pneumo.ch. MTT performed as an outpatient or inpatient significantly improves dyspnea, endurance, quality of life, and decreases hospitalizations due to exacerbations [15].

Oxygen: Oxygen can be used prognostically either for palliative reasons or in the presence of hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension. Mobile patients benefit most from ambulatory liquid oxygen. Potentially eligible patients for long-term oxygen treatment should be identified by primary care physicians and referred to pulmonologists for titration, prescription, and monitoring [16].

Surgery: Surgical lung volume reduction (LVR) is considered in patients with significant distress and limitations on low exertion, severe hyperinflation, and predominantly heterogeneous emphysema. With correct selection, a survival advantage may even be expected [17]. The procedure can be performed with acceptable risk; prior controlled tobacco abstinence is still required. Ultima ratio remains lung transplantation.

Endoscopic LVR: L ung volume reduction can also be induced with partially endoscopic, relatively simple and low-stress procedures (use of valves or coils). Patient selection is crucial here, and only a few centers have sufficient experience and controlled results to date [18].

coping strategies (“disease management”): Disease-specific training often occurs as part of MTT. Family physicians are challenged to educate patients in recognizing an exacerbation, develop an emergency plan, and help break the downward spiral of illness, anxiety, isolation, and depression [19].

Vaccinations: Influenza vaccination reduces exacerbation rates and, especially in elderly patients, hospitalizations and mortality. It should be done annually. Recommendations for polyvalent pneumococcal vaccination have recently been questioned. Booster vaccinations with the 23-valent vaccine (PPV 23) are not recommended at this time. The Swiss vaccination schedule currently provides a single dose of the 13-valent pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-13) for persons at increased risk of complications from pneumococcal disease. This vaccination should be given at a minimum interval of four weeks from an influenza vaccination. Currently, however, the cost of pneumococcal vaccination is covered only for children up to five years of age.

Acute exacerbations

Acute exacerbations, the most common complications in practice, are defined by persistent increases in dyspnea, cough, or sputum production. Treatment includes an increase in inhaled medications, oral corticosteroids, which may be used for a shorter period of time at most (only for five days) at a dose of 50 mg prednisone equivalent [20], and antibiotics if there is increased purulence of the sputum.

Controversies

Expectations that pharmacotherapy could slow the progression of COPD remain unfulfilled to date. It is not clear whether early use of inhaled agents can halt the loss of lung function, or whether combination therapies consisting of LABA + LAMA + ICS benefit patients. The use of ICS will have to be questioned further. The risk-benefit ratio has probably been judged too favorable so far. In the future, greater emphasis will be placed on the treatment of comorbidities and on therapy that is as adapted as possible to the phenotype.

Prof. Dr. med. Robert Thurnheer

Literature:

1. Ackermann-Liebrich U, et al: American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 1997; 155: 122-129.

2nd Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, updated 2014.

3 Halbert RJ, et al: ERJ 2006; 28: 523-532.

4. Vestbo J, et al: American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2013; 187: 347-365.

5. Rothe T: Praxis 2012; 101: 1481-1487.

6. Vestbo J: Clinics in chest medicine 2014; 35: 1-6.

7. Russi EW, et al: Respiration 2013; 85: 160-174.

8. Aaron SD: American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2009; 179: 335-336.

9. Fritsch K, et al: Swiss medical weekly 2005; 135: 116-121.

10 Calverley PM, et al: NEJM 2007; 356: 775-789.

11. Tashkin DP, et al: NEJM 2008; 359: 1543-1554.

12. Jochmann A, et al: Swiss medical weekly 2012; 142: w13567.

13 Suissa S, et al: Lancet 2009; 374: 695-703.

15, Casaburi R, ZuWallack R: NEJM 2009; 360: 1329-1335.

16 Calverley PM: Thorax 2000; 55: 537-538.

17. Meyers BF, et al: The Annals of thoracic surgery 2001; 71: 2081.

18. Herth FJ, et al: Respiration 2010; 79: 5-13.

19. Bourbeau J: Copd 2011; 8: 143-144.

20 Leuppi JD, et al: JAMA 2013; 309: 2223-2231.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Although a very big breakthrough in COPD treatment has not yet been achieved, a new understanding of the disease has contributed to a variety of possible interventions and a noticeable change.

- Patients are often not treated according to the guidelines.

- Inhalation devices are becoming more and more user-friendly.

- Patients with COPD generally benefit from physical exercise.

- Pharmacotherapy has not yet been able to slow the progression of COPD.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(8): 18-21