Malnutrition increases with age. The leading symptom is unwanted weight loss. In nutrition therapy, the supervision of a qualified nutritionist is of great importance.

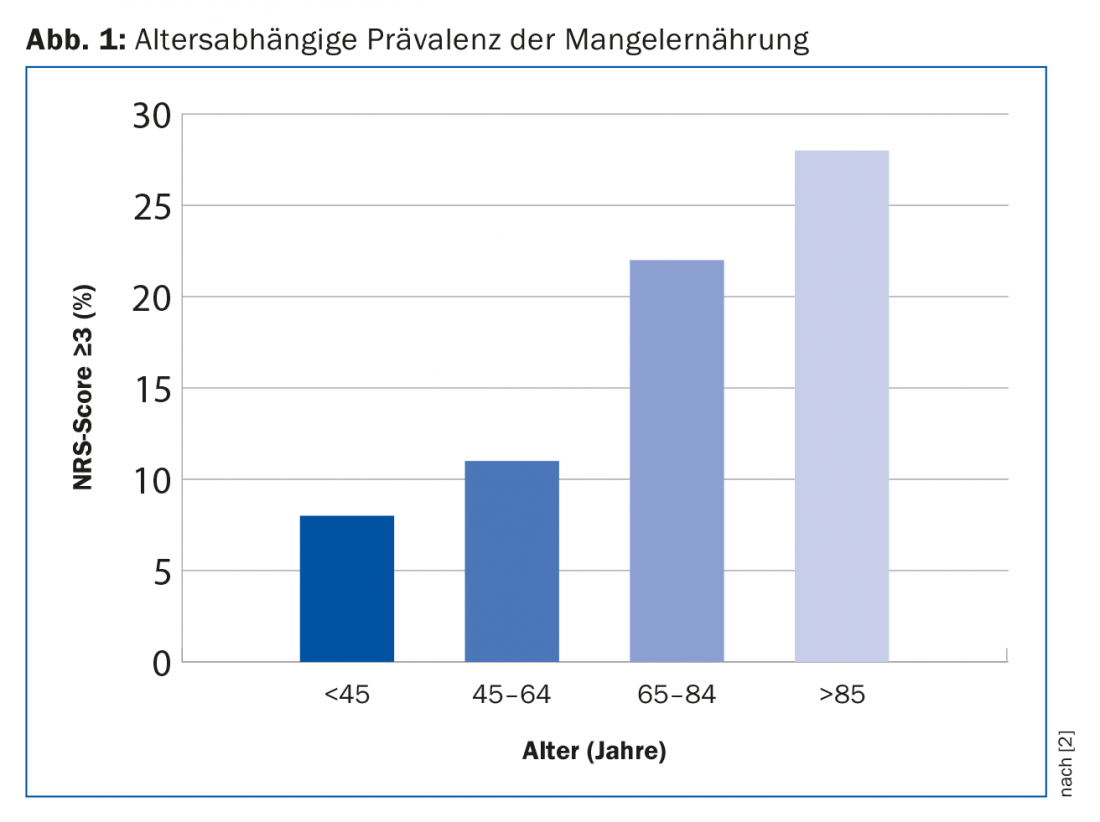

Although we live in a country characterized by prosperity, the number of malnourished people is astonishingly high. Especially in hospitals and nursing homes, 20-60% of internal medicine and surgery patients present energy and/or protein malnutrition, with the highest prevalence observed in geriatric (56.2%), oncology (37.6%), and gastroenterology (32.6%) departments. 43% of patients with age over 70 years were affected by malnutrition in contrast to only 7.8% of patients with age under 30 years [1]. Also, in our own study of over 32,000 patients, we observed that the prevalence of malnutrition is directly age-dependent (Fig. 1) [2]. Thus, malnutrition occurs frequently and increases with age.

To date, national and international professional societies have not been able to agree on a uniform definition of malnutrition. Nevertheless, all experts consider unwanted weight loss as a leading symptom of malnutrition. Anyone who has lost more than 5% of their body weight in one month or more than 10% in six months meets a key criterion of malnutrition. Other important markers of the presence of a risk for malnutrition, which are often easier to ascertain in everyday life, are an unintentionally reduced food intake and a body mass index of less than 20 kg/m2 [3].

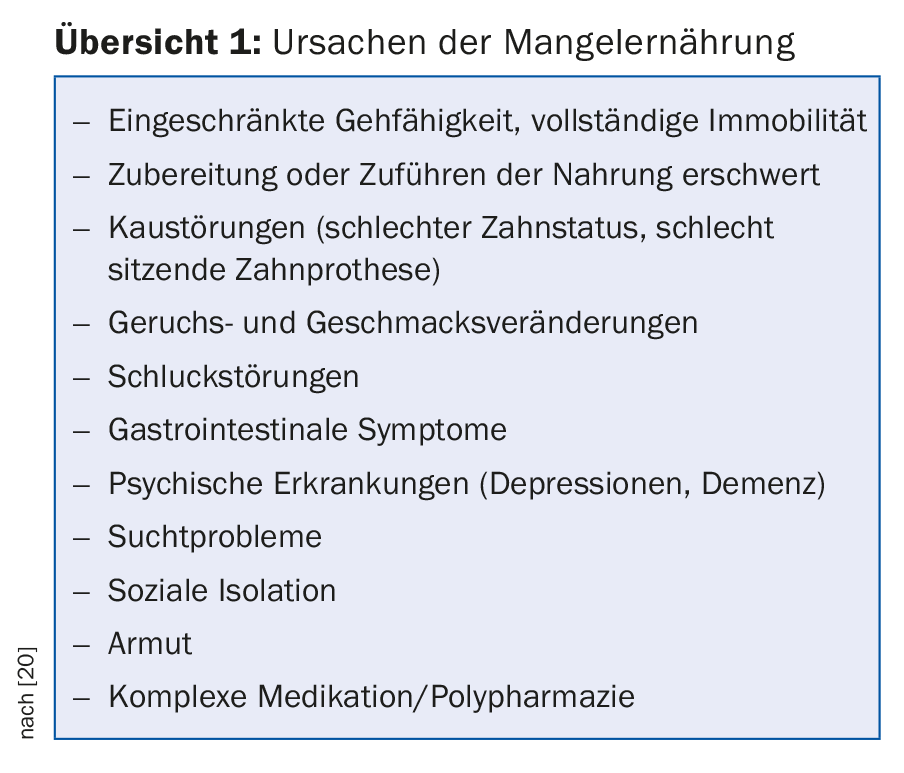

The causes for the occurrence of malnutrition are complex. An overview of possible causes that can lead to malnutrition is shown in Overview 1 . First of all, changes in body composition occur over the course of a person’s life: Muscle is lost and replaced by fat mass as early as the age of 30. This change affects physical performance, so that some seniors are no longer able to shop for or prepare groceries, for example. In addition, the sense of thirst and the desire for food are reduced in old age. This so-called age-related anorexia is explained by an increased activity of gastrointestinal satiety factors. The bioavailability of iron, vitamin B12, and calcium is reduced due to decreased gastric acid resection with age. Many seniors spend less time outdoors, so their skin synthesizes less vitamin D via sun exposure. Men and women over 60 years of age are therefore recommended to supplement with 800 IU/day to achieve a target blood concentration of 25(OH)D of 50 nmol/l. In addition, the ability to respond adequately to metabolic stress is impaired. Even a harmless illness can therefore often lead to a deterioration in nutritional status and the development of malnutrition in old age. These changes in old age rarely occur in isolation, but rather in parallel and are exacerbated by polypharmacy [4].

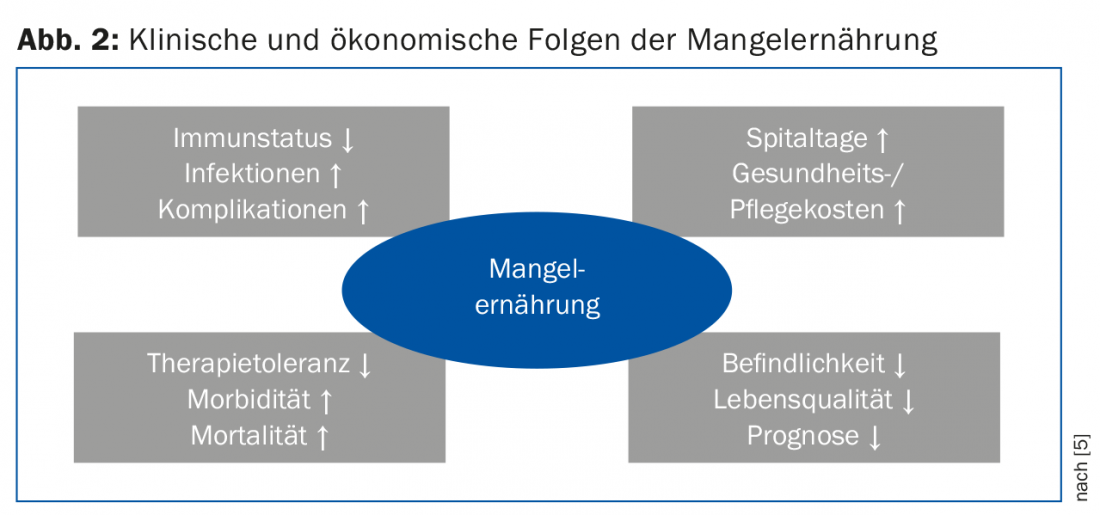

The presence of malnutrition has both clinical consequences for the patient and economic consequences (Fig. 2) [5]. Malnutrition has a structural and functional impact on virtually all organ systems. For example, the immune status of patients decreases, increasing the risk of infections and complications. As a consequence, treatment tolerance is reduced and the quality of life of patients decreases, leading to an overall increase in morbidity and mortality [5]. Reduced nutritional status typically causes patients to stay in the hospital longer and increases the cost of care. Systematic analyses in Germany show direct additional costs due to malnutrition in the order of approximately 9 billion euros per year [5]. In an older study commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health to determine the costs of malnutrition in Switzerland, the costs could be estimated at an average of 526 million Swiss francs per year [6]. We may assume that today the costs are substantially higher.

Recognition of malnutrition

In hospitals, nursing homes or even in the doctor’s office, regular checks should be made to determine whether a patient is suffering from malnutrition. Various questionnaires have proven useful for screening. The Nutritional Risk Screening [7] is recommended for hospitalized patients and the Mini Nutritional Assessment [8,9] is recommended for elderly patients. The questionnaire for geriatric patients is suitable for both inpatient and outpatient settings. All questionnaires have as a common feature the query of an unintentional weight loss and a restricted food intake.

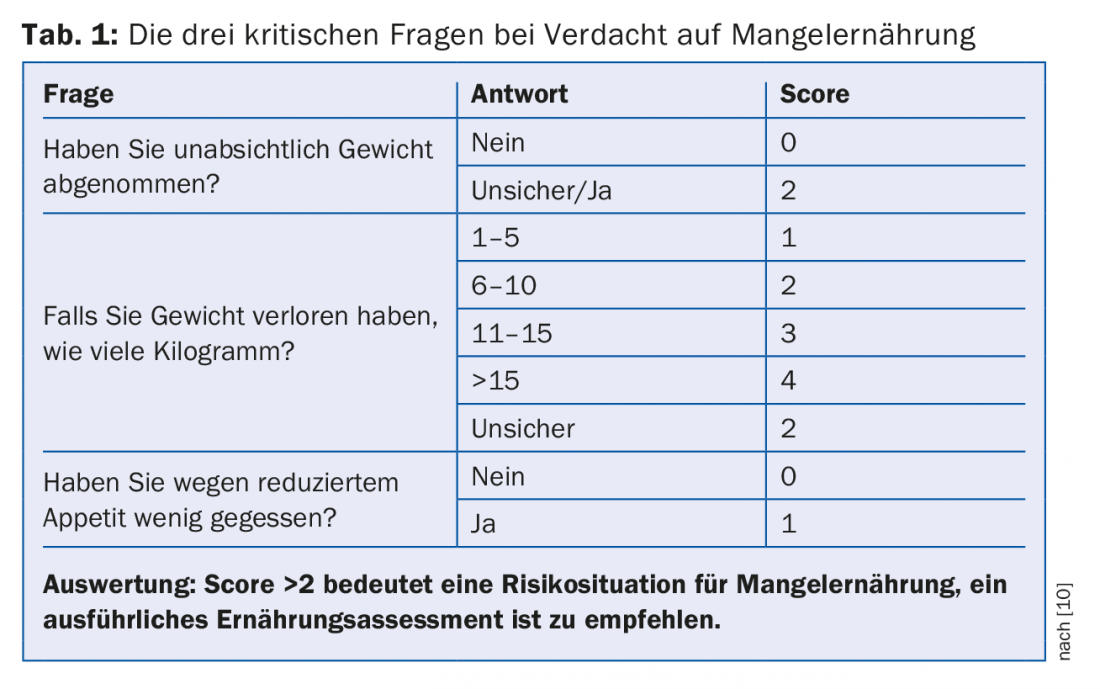

The recognition and, if possible, the prevention of malnutrition should not only take place in the acute case of illness in the hospital, but already by the family doctor. However, the limited time available in medical practice requires simple tools to check for the presence of malnutrition. Initially, it is recommended that weight be measured and documented twice a year as a routine for each patient. Without spending a lot of time, three very effective questions can be asked during the interview with the patient, which are listed in Table 1 together with the possible answers. A total score of two or more indicates a risk situation, which should lead to a detailed nutrition assessment by a qualified (legally recognized) dietitian [10].

The key question about appetite plays a central role in the detailed anamnesis. If appetite is normal or increased, the predominant causes of malnutrition are hyperthyroidism, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, malabsorption, or pheochromocytoma. In most cases, however, the appetite is reduced, so that the workup should cover the entire spectrum of internal medicine and proceed according to leading symptoms [11].

In addition to the detailed interview, a brief physical examination should also be performed on the patient. Some malnourished patients are obviously recognizable as such, as the protruding bone edges and ribs can be seen directly. Muscle atrophy and complete absence of subcutaneous adipose tissue are easily seen and also palpable. In addition to muscle and adipose tissue status, the oral cavity is additionally an important anatomic region of the body where clinical signs of nutrient deficiency or malnutrition manifest. Lips, tongue, oral mucosa and gums in particular also indicate vitamin and/or mineral deficiencies, often long before other areas of the body are affected. Disorders such as burning of the mouth and tongue and changes in taste can also be recorded in this way [11].

Nutrition therapy for malnutrition

If a patient is identified as malnourished or at risk for malnutrition, a qualified dietitian should be consulted and, if indicated, individualized nutrition therapy should be initiated after nutritional assessment has been completed. In younger patients, the reduction of morbidity and mortality is the top priority; in contrast, in geriatric patients, the preservation of function, independence, and quality of life is paramount [12]. Nutritional therapy in the elderly often goes beyond mere dietary measures and encompasses a wide range of different interventions, all of which can contribute to adequate nutritional intake. These measures include, for example, a visit to the dentist, special eating utensils or the inclusion of a home help or a meal service [12].

Nutritional therapy aims to ensure that patients have adequate energy, macro- and micronutrients, and fluids. The guideline value for fluid intake is 30 ml per kg body weight. If there is increased fluid loss due to sweating, fever, diarrhea or vomiting, these losses must be compensated for quickly. The resting energy requirement decreases in the course of life; the guideline value for energy intake in seniors is about 30 kcal per kg body weight per day. Depending on the nutritional status, physical activity and metabolic situation, the energy requirement must be adjusted accordingly. In this context, regular checking of body weight gives an indication of whether sufficient energy is being absorbed. In contrast to the energy requirement, the protein requirement does not decrease and even increases somewhat. With an adequate protein supply, the loss of muscle mass can be counteracted. Daily protein intake should therefore be at least 0.8-1.2 g/kg body weight in the absence of renal insufficiency [12,13]. In addition to dietary recommendations, the importance of physical activity in old age should be noted here, which also promotes the preservation of muscle mass, function and quality of life [14].

To achieve nutrition goals, a regular meal structure is helpful. The main meals should always include a starch side dish such as potatoes and a protein side dish. At breakfast, the protein side dish could be cheese, egg, or cottage cheese; at lunch, for example, it could be meat, egg, or even vegetarian sources of protein. Additionally, small snacks can be incorporated to provide adequate energy and protein. The choice of food should be based on calories and energy. protein-dense foods such as cream cheese, nuts or whole milk yogurt are preferred. Furthermore, meals can be enriched with fats, e.g. in the form of olive oil, or with sugar, honey or maltodextrin. Protein-rich products such as skim milk powder or protein powder can also be used for fortification [13].

If the patient cannot meet his or her needs through normal food intake, oral nutritional supplements (ONS) should be used. These can also be used as a snack between meals or as a meal replacement/supplement. In the context of nutrition therapy for malnourished seniors, the use of ONS is appropriate to stabilize and improve nutritional status [15,16]. National and European guidelines of nutritional medical societies recommend the use of ONS with a level of evidence A for older people with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition to reduce the risk of complications and also mortality [12,17].

If all the measures described for the therapy of malnutrition are not sufficient and a supply gap persists, tube feeding or, at the very end, parenteral nutrition should be discussed together with the patient. The prerequisite for the use of artificial tube feeding is always that the expected benefits should outweigh the burdens. The aspects of prognosis and quality of life should always be included in the decision for or against artificial tube feeding and should be reassessed regularly [18]. Under these circumstances, tube insertion is indicated as soon as it is foreseeable that a patient does not have sufficient oral nutritional intake, e.g. due to dysphagia. cannot take food orally for more than three days. Enteral nutrition is always preferable to parenteral nutrition. If a patient only needs to be tube fed for a short period of time, nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding tubes should be used. For long-term tube feeding starting at about four weeks, insertion of a percutaneous gastrostomy (PEG) should be discussed [19]. Parenteral nutrition is indicated only when the patient no longer has a functioning gastrointestinal tract [18].

Take-Home Messages

- Malnutrition is common and increases with age.

- The leading symptom of malnutrition is unwanted weight loss.

- Nutrition therapy for geriatric patients focuses on maintaining function, independence and quality of life, and the care of a qualified, certified nutritionist or therapist is of great importance.

- For healthy seniors, daily guidelines are 30 kcal for energy, 0.8-1.2 g for protein, and 30 ml for water per kg of body weight.

- As part of nutritional therapy for malnourished seniors, the use of sip feeds is appropriate.

Literature:

- Pirlich M, et al: The German hospital malnutrition study. Clinical Nutrition 2006; 25: 563-572.

- Imoberdorf R, et al: Prevalence of undernutrition on admission to Swiss hospitals. Clinical Nutrition 2010; 29: 38-41.

- Bauer JM, Kaiser MJ, Sieber CC: Evaluation of nutritional status in older persons: nutritional screening and assessment. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 2010; 13: 8-13.

- Bauer JM, et al: for the participants of the BANSS Symposium 2006: Malnutrition, sarcopenia and cachexia in the elderly: from pathophysiology to treatment. Conclusions of an international meeting of experts, sponsored by the BANSS Foundation. Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift 2008; 133: 305-310.

- Löser C: Malnutrition in hospital: the clinical and economic implications. Deutsches Arzteblatt international 2010; 107: 911-917.

- Frei A: Malnutrition in hospital – medical costs and cost-effectiveness of prevention. Report commissioned by the FOPH. 2006.

- Kondrup J, et al: ESPEN Guidelines for Nutrition Screening 2002. Clinical Nutrition 2003; 22: 415-421.

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ: Mini Nutritional Assessment: a practical assessment tool for grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Facts and Research in Gerontology 1994; 4: 15-59.

- Rubenstein LZ, et al: Screening for undernutrition in geriatrc practice: developing the short-form Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA-SF). Journal of Gerontology: Biology Science and Medical Science 2001; 56: M366-M72.

- Ferguson M, et al: Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patients. Nutrition 1999; 15: 458-464.

- Imoberdorf R, et al: Malnutrition – undernutrition. Swiss Medical Forum 2011; 11: 782-786.

- Volkert D, et al.: Guideline of the German Society of Nutritional Medicine (DGEM) in collaboration with GESKES, AKE and DGG: Clinical Nutrition in Geriatrics – Part of the ongoing S3 guideline project Clinical Nutrition. Current Nutritional Medicine 2013; 38: e1-e48.

- Imoberdorf R, et al: Malnutrition in old age. Swiss Medical Forum 2014; 14: 932-936.

- Federal Office of Sport FOSPO, Federal Office of Public Health FOPH, Health Promotion Switzerland, bfu – Swiss Council for Accident Prevention, Suva, Network for Health and Physical Activity Switzerland: Gesundheitswirksame Bewegung. Magglingen. FOSPO 2013.

- Stratton RJ: A review of reviews: a new look at the evidence for oral nutritional supplements in clinical practice. Clinical Nutrition Supplements 2007; 2: 5-23.

- Uster A, Ruehlin M, Ballmer P: Drinkable nutrition is effective, expedient and economical. Swiss Journal of Nutritional Medicine 2012; 4: 7-11.

- Volkert D, et al: ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: Geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition 2006; 25: 330-360.

- Bischoff S, et al: S3 guideline of the German Society of Nutritional Medicine (DGEM) in collaboration with GESKES and AKE. Artificial nutrition in the outpatient setting. Current Nutritional Medicine 2013; 38: e101-e154.

- Haller A: Enteral tube feeding. Therapeutic Review 2014; 71: 155-161.

- Solver C: The unintentional weight loss of the elderly. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2007; 49: 3411-3420.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(3): 12-16