The fact that a microbial imbalance is relevant to disease is regarded as certain. The exact nature of the associated processes is the subject of current studies. It is also considered proven that the exposome can favor or worsen the condition of skin affected by acne. In terms of therapeutic implications, the evidence is still limited, but this is a promising area of research.

To date, the pathophysiological relationships of acne vulgaris have not been fully elucidated [1,2]. The role of the microbiome in the development and maintenance of acne has increasingly become the focus of interest in recent years. The interrelationships are very complex and a wide variety of hypotheses are currently being researched. In the context of the virtual Dermatology and Allergology Refresher, PD Dr. med. Maja A. Hofmann, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin (D) gave an up-to-date overview of the role of the skin microbiome.

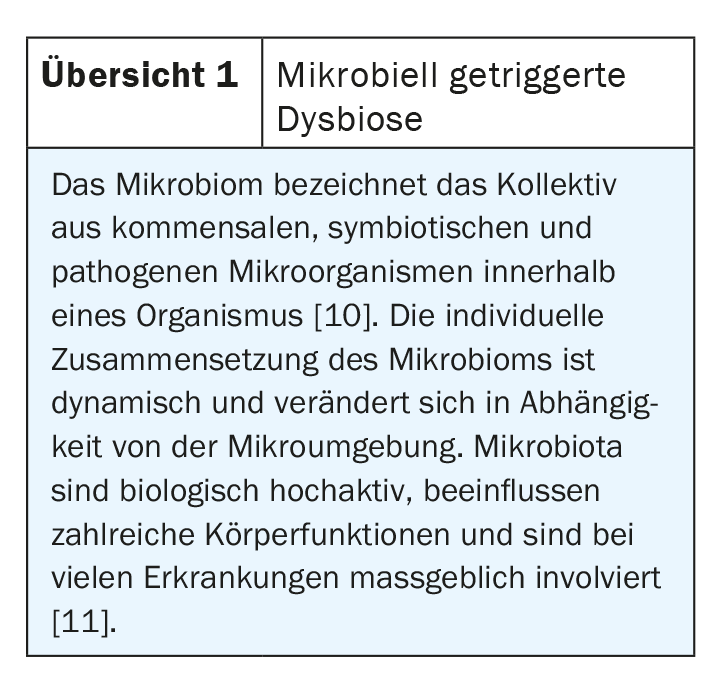

Microbial dysbiosis in focus as a pathogenetic factor.

The fact that the composition and activity of the skin microbiome is disturbed in acne has been empirically proven several times. Which microbes are involved and how is the subject of numerous current studies [3]. “Everyone has a different microbiome, and dysbiosis often occurs – not only in acne but in other diseases as well,” the speaker explained. This modification of the skin barrier triggered by changes in the microbiota can lead to a pathological state (overview 1). In a healthy state, bacteria, viruses and parasites are prevented from entering the body by primary protective barriers and associated immune defense components. If microorganisms nevertheless penetrate tissues, lymph and bloodstream, they are attacked by the secondary barrier, a highly complex system of innate (phagocytes, natural killer cells, complement system) and adaptive (“specific”) components of the immune system. The immune system orients itself on the one hand to individually specific marker molecules on the surface of the body cells (“major histocompatibility complex”, MHC system) and on the other hand to microbial molecules (“pathogen-associated molecular patterns”, PAMPs).

Studies of the interplay of the various bacteria on the skin will provide further insights into the pathophysiology of acne vulgaris in the coming years, Dr. Hofmann said [2]. Propionibacterium acnes produces the small molecule coproporphyrin III, which induces Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) to form a biofilm that is pathogenetically poor and results in an immune response, the speaker explained, referring to an article published in Nature 2018 [4].

In an article published in 2020 by Dreno et al. a decrease in the diversity of the skin microbiome as a result of increased colonization with Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) triggered by hormonal changes and increased sebum reduction induced by this is described as a pathogenetically relevant factor [1]. Increased colonization of Cutibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermis (S. epidermis) is still thought to be characteristic of acne. C. acnes contains numerous biosynthetic gene clusters and lipases involved in the production and release of antimicrobial and immunomodulatory molecules and can thereby alter the microenvironment. There are also findings that in skin affected by acne, the diversity of C. acnes phylotypes is reduced [5,6].

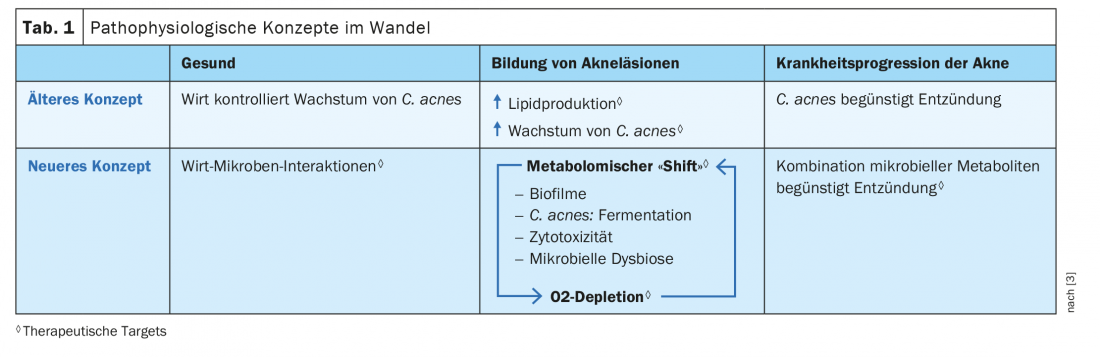

Referring to results of metagenomic sequencing studies, a 2018 article by O’Neill and Gallo challenges the concept that sebum production-triggered overgrowth of hair follicles with C. acnes is a sole driver of inflammation and acne progression [3]. The authors postulate an alternative disease model in which a combination of different microbial metabolites within a bidirectional interaction structure acts as a driver of the inflammatory gene associated with acne (Table 1).

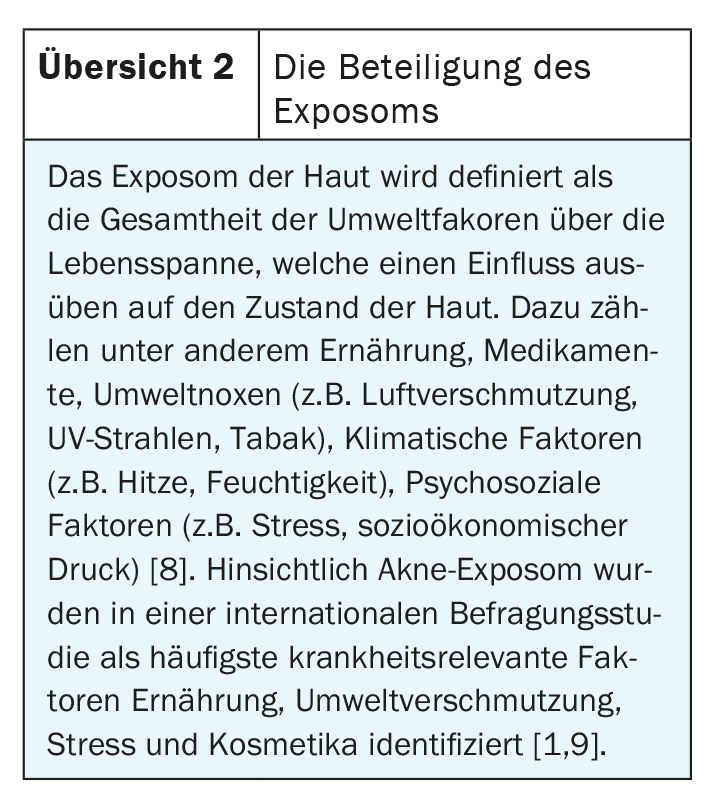

The exposome is also involved

In addition to the numerous internal triggers, external factors also contribute to a change in the germ spectrum of the skin. The exposome, i.e. the totality of disease-relevant environmental factors, is also involved in this (overview 2) [7]. The skin exposome is defined as the totality of environmental factors over the life span that exert an influence on the condition of the skin and skin diseases [7]. These include, for example, diet, medications, environmental toxins, climatic factors, psychosocial factors [8]. It is important to advise patients that a balanced diet can help stabilize acne, she said [2]. Possible trigger factors include dairy products and sweets (especially chocolate). Among medications, antidepressants and antiepileptics can have a negative impact on the condition of acne sufferers. It is also known that high humidity combined with high temperatures can contribute to symptom exacerbation by altering the biofilm. And it is now also known that stress plays a not insignificant role. According to the speaker, it is not unimportant to discuss these factors, but experience has shown that there is often little time for this in everyday clinical practice.

Therapeutic use: there are obstacles to overcome

Maintaining the balance of the cutaneous microbiome within the follicles and on the surface of the skin is considered essential in acne-prone and acne-affected skin [1]. However, the research findings in this regard are still very incomplete [3]. According to O’Neill and Gallo 2018, longitudinal metagenomic analyses of phenotypic changes in the microbiome during antibiotic or isotretinoin therapy can be informative-particularly in patients who are refractory to treatment or in whom symptoms recur after treatment. The authors consider a better understanding of the interactions of C. acnes and S. epidermis as essential – on the one hand for a better understanding of the pathophysiology and on the other hand for the detection of secondary metabolites, which can be used therapeutically [3]. While oral and topical antibiotics are the proven mainstay of therapy, there are still many gaps in knowledge regarding microbiota as therapeutic targets as well as the option of eradicating important commensals. Major hurdles to scientific studies in this regard include a lack of molecular techniques for genetic manipulation of C. acnes and the lack of a representative in vivo model for acne. Thus, there are still many unanswered questions regarding the interplay of microbial and non-microbial factors in the pathogenesis of acne and how these findings can be translated into therapeutic applications.

Source: FomF (D) Dermatology and Allergy 2020

Literature:

- Dréno B, et al: J Cosmet Dermatol 2020; 19(9): 2201-2211.

- Hofmann MA: Acne and rosacea – what helps best and for whom? PD Dr. med. Maja A. Hofmann, Dermatology and Allergology Refresher, Hofheim (D), 12.09.2020.

- O’Neill AM, Gallo RL: Microbiome 2018; 6(1): 177.

- Byrd AL: Nat Rec Microbiol 2018; 16(3): 143-155.

- Kwon HH, Suh DH. Internat J Dermatol. 2016; 55(11): 1196-1204.

- Qidwai A, et al: Human Microbiome J 2017; 4: 7-13.

- Passeron T, et al: JEADV 2020; 34 (IssueS4): 4-25.

- Dreno B, et al: JEADV 2018; 32: 812-819.

- Dreno B, et al: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereolb 2020; 34: 1057-1064.

- Lederberg J, McCray AT: Scientist 2001; 15(7): 8.

- Hinghofer-Szalkay H: A Journey through Physiology. Defense strategies, microbial colonization of the body, em. Univ.-Prof. Dr.med. Helmut Hinghofer-Szalkay, http://physiologie.cc/XVII.1.htm

- Dréno B, et al: Nonprescription acne vulgaris treatments: Their role in our treatment armamentarium – An international panel discussion. J Cosmet Dermatol 2020; 19(9): 2201-2211.

- Hofmann MA: Acne and rosacea – what helps best and for whom? PD Dr. med. Maja A. Hofmann, Dermatology and Allergology Refresher, Hofheim (D), 12.09.2020.

- O’Neill AM, Gallo RL: Host-microbiome interactions and recent progress into understanding the biology of acne vulgaris. Microbiome 2018; 6(1): 177.

- Byrd AL: The Human Skin Microbiome. Nat Rec Microbiol 2018; 16(3): 143-155.

- Kwon HH, Suh DH. Recent progress in the research about Propionibacterium acnes strain diversity and acne: pathogen or bystander? Internat J Dermatol. 2016; 55(11): 1196-1204.

- Qidwai A, et al: The emerging principles for acne biogenesis: a dermatological problem of puberty. Human Microbiome J 2017; 4: 7-13.

- Passeron T, et al: Clinical and biological impact of the exposome on the skin. JEADV 2020; 34 (IssueS4): 4-25.

- Dreno B, et al: The influence of exposome on acne. JEADV 2018; 32: 812-819.

- Dreno B, et al: The role of the exposome in acne: results from an international patient survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereolb 2020; 34: 1057-1064.

- Lederberg J, McCray AT: ‘Ome Sweet ‘Omics – A Genealogical Treasury of Words, Genealogical Treasury of Words. Scientist 2001; 15(7): 8.

- Hinghofer-Szalkay H: A Journey through Physiology. Defense strategies, microbial colonization of the body, em. Univ.-Prof. Dr.med. Helmut Hinghofer-Szalkay, http://physiologie.cc/XVII.1.htm

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2020; 30(6): 44-45 (published 12/6/20, ahead of print).