Porphyrias are a group of very rare, genetically determined metabolic diseases with a disorder of heme biosynthesis. The typical symptom triad in a relapse consists of abdominal pain, cerebral symptoms, and peripheral neuropathy. Another important sign is the red discoloration of the urine. For the treatment of an acute episode, intravenous administration of hemarginate (Normosang®) is the therapy of choice. When caring for patients, it is especially important to avoid medications that trigger relapses (emergency card). Patients with newly diagnosed porphyria should be included in the Munich Registry for Acute Porphyrias.

Porphyrias are a group of very rare, genetically determined metabolic diseases that are based on a disorder of heme biosynthesis. In the human organism, heme is a component of hemoglobin, which is responsible for oxygen transport, and of the oxygen storage protein myoglobin, in which it occurs as an iron-bearing prosthetic group, as well as of numerous cytochromes that are involved in energy metabolism in virtually every cell in the respiratory chain. For the continuous turnover of these proteins, heme must be constantly provided.

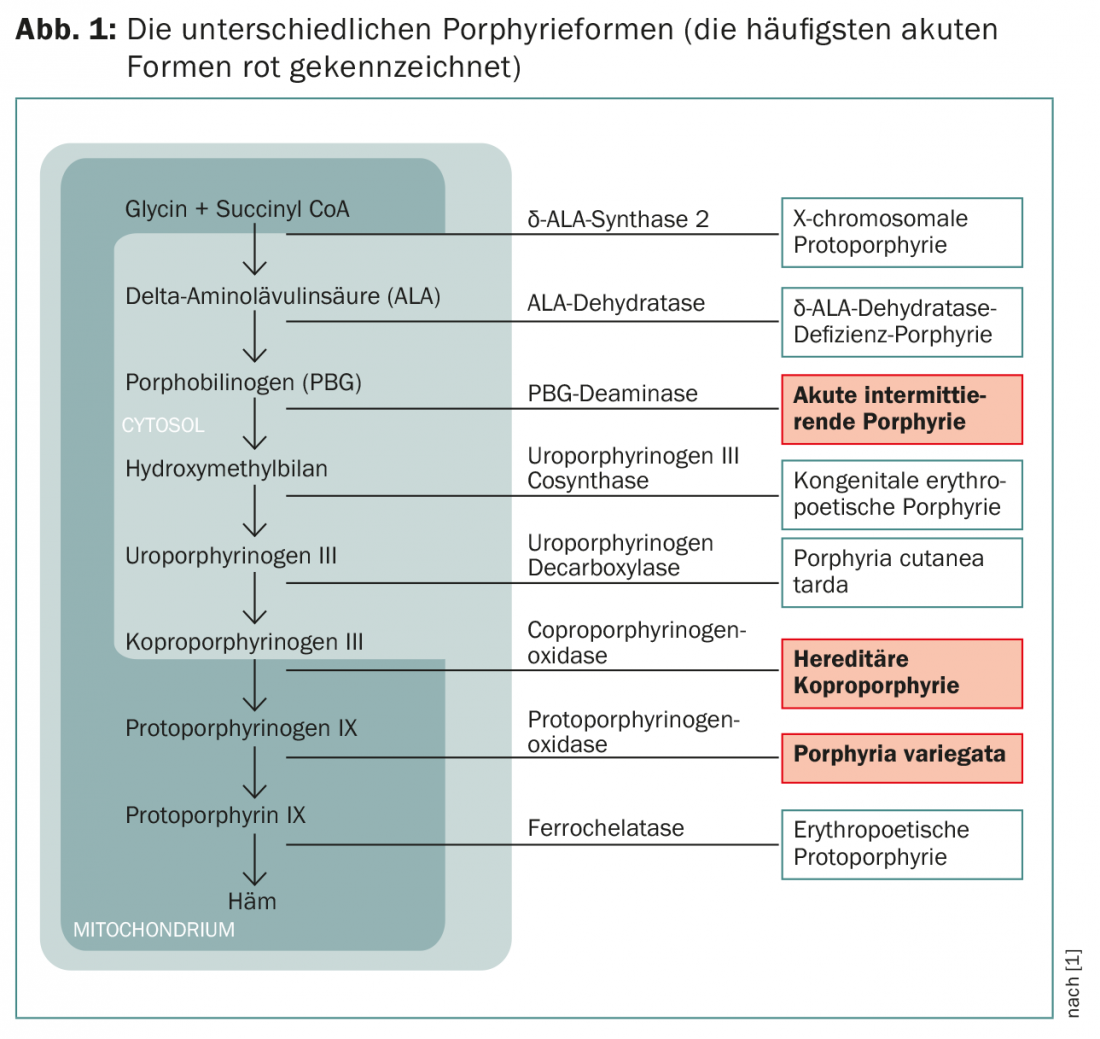

Eight enzymes are involved in the biosynthesis of heme; regulation of synthesis occurs via feedback inhibition of δ-ALA synthase, the first enzyme in biosynthesis, by the end product heme. There are two isoenzymes in the organism: δ-ALA synthase 1 is found in all tissues, and δ-ALA synthase 2 is found only in bone marrow. Due to their quantitative importance, the liver and bone marrow are the most important sites for heme synthesis.

Pathophysiology of porphyrias

Heritable (or rarely spontaneous) mutations in the genes of the enzymes of heme biosynthesis lead to a partial loss of function of the encoded enzyme. This partial loss of function (i.a. to 50%) is sufficiently compensated by stimulation of δ-ALA synthases so that heme deficiency does not normally occur. Carriers of the genetic predisposition therefore generally have no problem with the reduced metabolic performance of the affected enzyme. The situation becomes problematic when heme requirements increase, e.g., due to the use of a drug such as phenytoin, which induces heme-containing cytochrome P450 degradation enzymes in the liver. Then heme synthesis is very strongly stimulated, and a “traffic jam” occurs at the narrow point of the enzyme defect due to the reduction of activity to 50%: Intermediates of heme metabolism (especially the porphyrin precursors porphobilinogen and δ-aminolevulinate) accumulate in the cells, enter the extracellular space and distribute in the organism.

Three forms of porphyria

Depending on which enzyme is affected in acute porphyrias, a distinction is made between the common variant “acute intermittent porphyria” (AIP) and the rarer variants “porphyria variegata” (PV) and “hereditary coproporphyrinuria” (HKP) ( Fig. 1).

Symptoms depend on which metabolites accumulate. The porphyrin precursors, which are still water-soluble, penetrate nerves and cause neurological symptoms; the fat-soluble porphyrins are deposited in the skin and cause skin symptoms through exposure to UV radiation. These complaints are very diverse and often confusing, as they also occur in a large number of other diseases. The correct diagnosis is therefore usually made correspondingly late.

Symptoms: Abdominal pain, red urine, neurological disturbances.

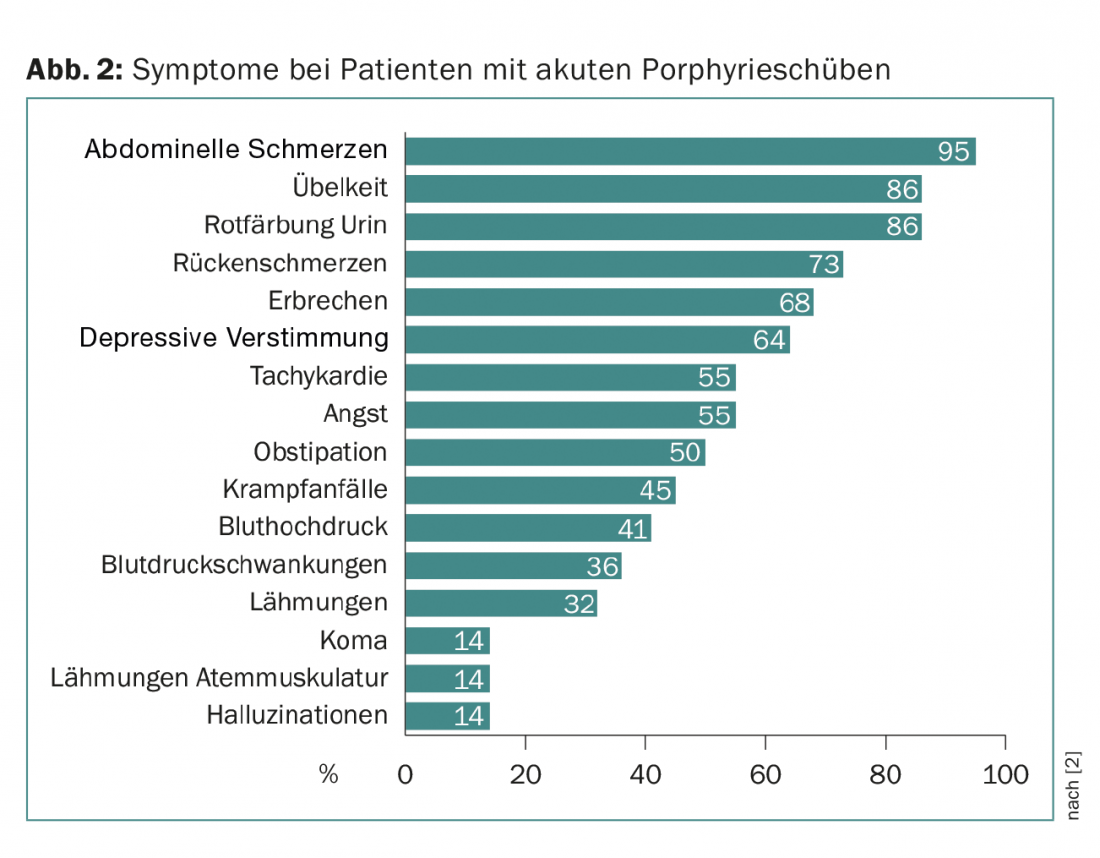

In all three forms, the acute onset of symptoms is referred to as a relapse. The relapses can be mild and are then mainly determined by abdominal pain. They occur repeatedly without success in making the correct diagnosis. Only in a severe episode in which, in addition to abdominal pain, signs of central symptoms (such as depressed mood, hallucinations, coma) and peripheral neurological symptoms (back pain, paralysis) occur (symptom triad), does the likelihood of making the correct diagnosis increase (Fig. 2).

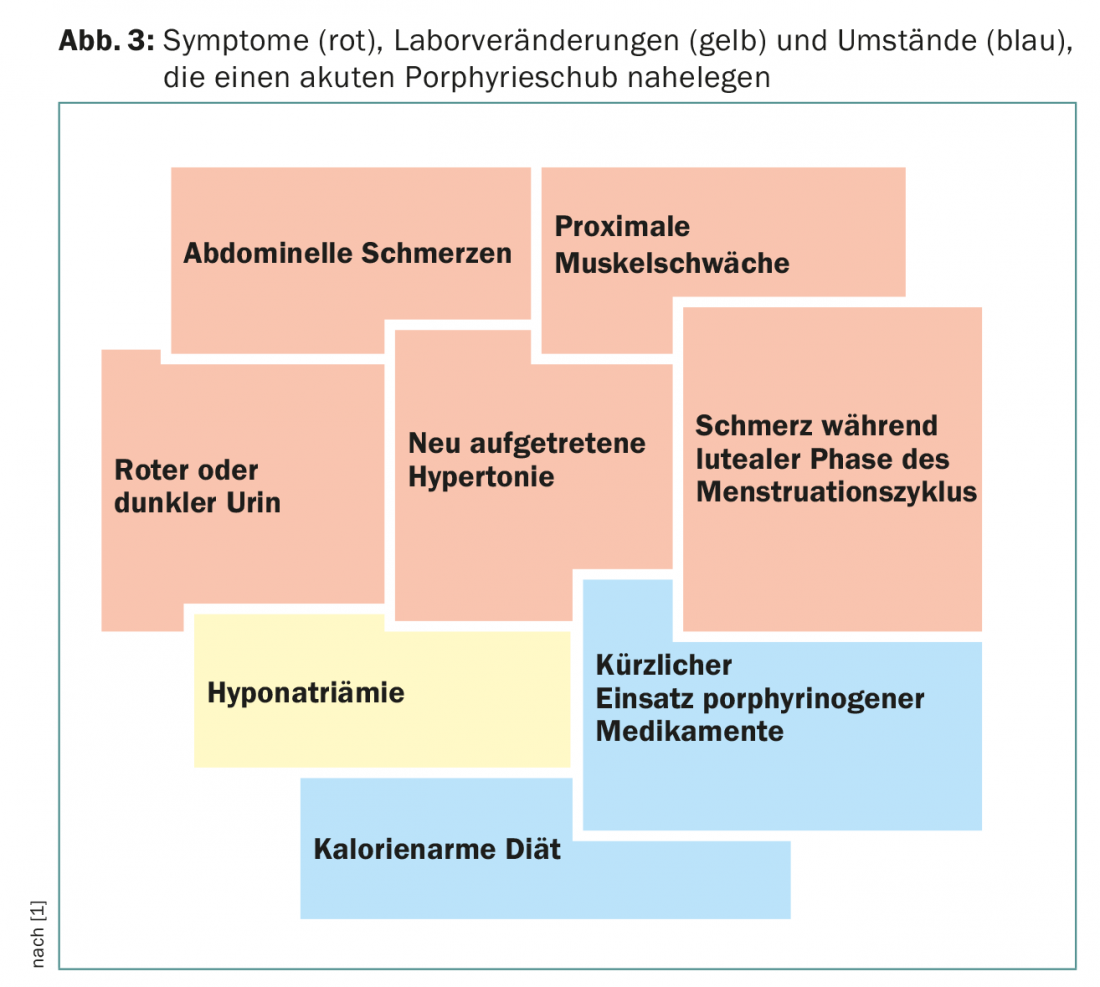

An important additional clinical sign is the red discoloration of the urine, which results from autooxidation of porphobilinogen to porphobilin. Together with laboratory changes such as hyponatremia, these symptoms suggest acute porphyria (Fig. 3). Patients are often cared for in intensive care units because of the severity of the symptoms, and it is often a young resident who remembers the rare disease because of its proximity to the state examination.

Hyponatremia can lead to seizures, which are not infrequently treated with carbamazepine or phenytoin, which are relapse-promoting drugs, in ignorance of the diagnosis. Cerebral symptoms can range from mild mental impairment to paranoid psychosis, delirium, or coma. In isolated cases, central mono- or hemiparesis occurs, and respiratory paralysis threatens the need for mechanical ventilation, so that a life-threatening situation may develop. In the setting of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), detected by MRI scan, cortical blindness with complete loss of visual acuity may occur.

A proportion of patients develop peripheral, predominantly motor neuropathy during the relapse. In a large proportion of patients, polyneuropathy is triggered by iatrogenic measures (administration of porphyrinogenic drugs) in ignorance of the presence of acute porphyria. The neuropathy is atypically distributed, i.e., the arms are affected more than the lower extremities, and the proximal muscles are more pronounced than the distal muscle groups. In one-third of patients, paralysis begins in the legs, with proximal emphasis in half. Asymmetric distribution of paresis is common. Signs of sensory neuropathy include sensory disturbances either sock-like and glove-like or in the trunk area like a “bathing suit.” In the rarer acute porphyrias, PV and HKP, additional skin symptoms occur. This is due to the fact that not only are porphyrin precursors elevated, but later intermediates of porphyrin synthesis are additionally deposited in the skin due to the position of the responsible enzyme defect.

Diagnostics

The increased detection of porphyrin precursors (δ-ALA and PBG) in the urine and not – as still often erroneously assumed – primarily of porphyrins suggests the suspicion of acute porphyria. Porphobilinogen is first measured semiquantitatively in a rapid test. The problem is that this test is not available in many laboratories. If the test is positive, quantitative analysis of PBG and δ-ALA follows: if the result is related to the urine creatinine level, a spontaneous urine sample is generally sufficient. 24-hour urine is no longer needed.

If porphyrin precursors are elevated, the presence of acute intermittent porphyria is confirmed by determination of PBG deaminase in erythrocytes and, if it is decreased, by mutation analysis (genetic testing). Diagnosis of the other two acute porphyrias requires urine and stool analysis for uro- and coproporphyrins, respectively.

Today, the final confirmation of the diagnosis is made by more than 300 different mutations in the PBG deaminase gene, i.e. practically every second amino acid position can be affected by a mutation. Therefore, the complete gene must always be sequenced at initial diagnosis. If the mutation is known, it is possible to test relatives specifically for the presence of this mutation.

Only about 10-15% of gene carriers develop a manifestation of porphyria in their lifetime. This is attributed, on the one hand, to the fact that confrontation with triggering agents does not occur in the knowledge of the predisposition and, on the other hand, to the fact that modifying genes protect against the manifestation of a relapse.

Therapeutic options

Previously, only infusion of high-dose glucose was available for therapy; this inhibits heme synthesis via downregulation of δ-ALA synthase activity. Today, intravenous administration of hemarginate (Normosang®) is the therapy of choice to “slow down” heme biosynthesis. The drug is administered as a short infusion over four days; a mixture with human albumin is useful because of the vein-irritating effect. Individual patients suffering from chronic relapsing episodes receive infusions via a port-a-cath. It is clear that relapse-promoting medications must be discontinued and not reapplied. Classic drugs that trigger relapses include the anticonvulsants phenytoin, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and valproic acid; barbiturates; the analgesics metamizole and phenylbutazone; sulfonamide antibiotics; and the antifungal drug griseovulvin. For example, lorazepam, diazepam, morphine, pethidine, chlorpromazine, and ondansetron are considered safe.

Patients receive an emergency ID card, which also refers to the website www.drugs-porphyria.com, where lists of thrust-promoting and safe medications are constantly updated. In individual cases, it is difficult to perform the assignment with certainty.

Interdisciplinary care

Diagnostics and therapy of patients with acute porphyrias are nowadays performed in an interdisciplinary team with hematologists, gastroenterologists, neurologists, anesthesiologists, laboratory physicians, dermatologists, gynecologists, and geneticists [1]. Of particular importance are the following aspects:

- Chronic recurrent relapses

- Treatment of severe, relapse-related, neurological complications.

- Preparation and execution of anesthesia

- Avoidance of misdiagnosis

- Care of pregnant patients with porphyria

- Differential diagnosis of possible skin changes

- Reliability of mutation analysis.

New diagnosis: inclusion in the porphyria register

Due to the rarity of the diseases, information on the course, severity of clinical expression and impairment of quality of life, possible side effects of treatments, etc. can only be obtained from registries. As of February 2016, 60 patients with acute porphyrias have been documented in the Munich Acute Porphyrias Registry. Newly diagnosed patients should be reported to this registry [2]. A website on this is under construction (www.akuteporphyrie.de).

Literature:

- Petrides PE (ed.), et al: The acute porphyrias, an information brochure for physicians. 4th edition 2015 Munich (available from Orphan Europe Ulm).

- Bronisch O, et al: Acute Intermittent Porphyria in Germany: Interim Analysis of 45 Patients from a single institution (Munich). International Congress on Porphyrins and Porphyrias, Düsseldorf, 9/2015.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(2): 16-19.