For those who need care for their mental illness but cannot or do not want to do so in an inpatient setting, there is an alternative: home treatment is increasingly establishing itself in the Swiss healthcare system. How does this concept actually work?

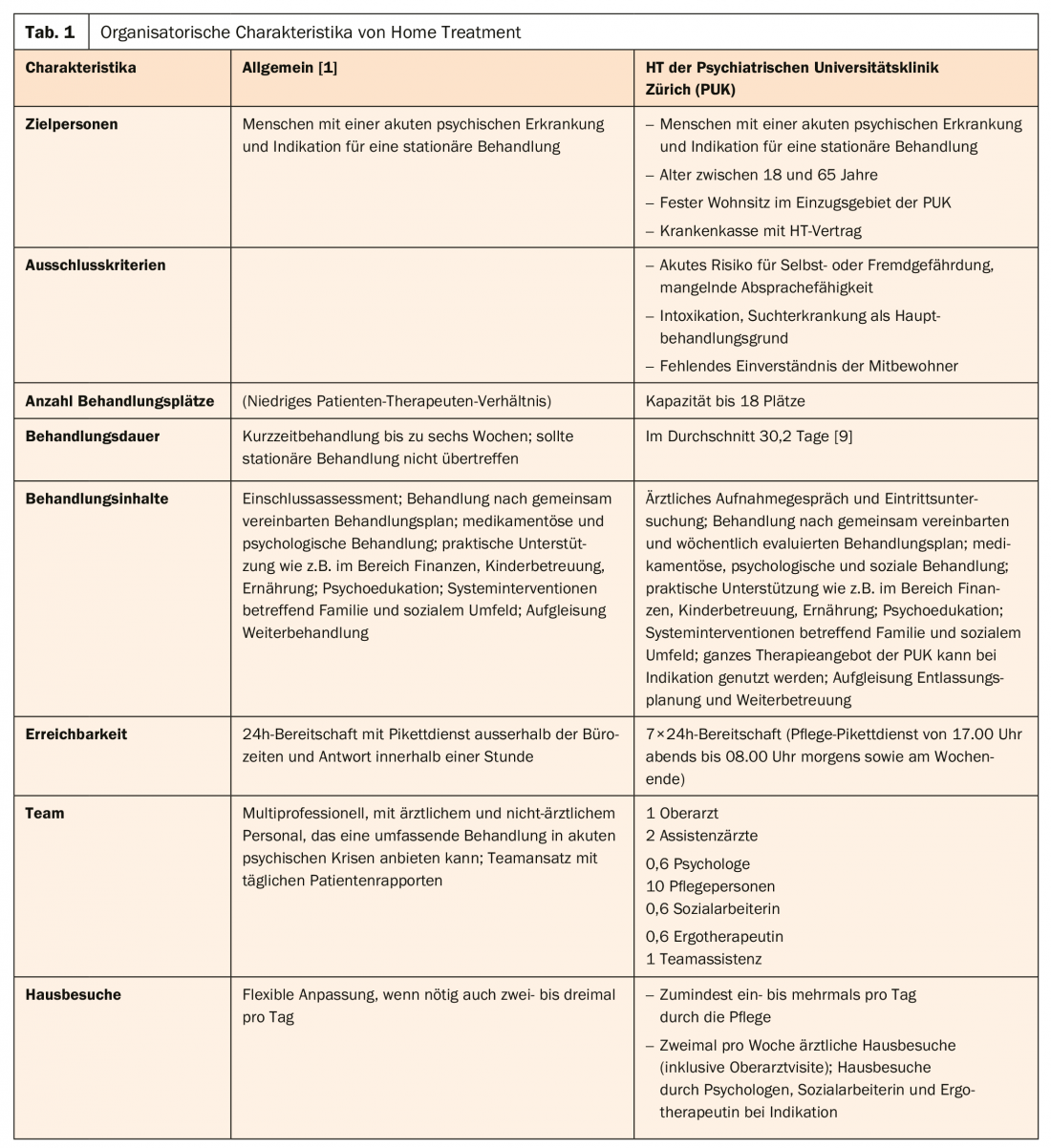

The term Home Treatment (HT) refers to an inpatient-equivalent alternative for people with acute mental illness who wish to receive professional treatment in their familiar environment. Synonyms are also used in German for community-integrated acute treatment or mobile crisis intervention and in English for the term “Crisis Resolution Team”. HT is aimed primarily at patients in need of inpatient treatment and lasts about the same length of time as standard conventional psychiatric hospital treatment. The primary goal of HT is to fully replace or appropriately shorten inpatient treatment days. In the latter case, this means that the HT team thereby also assumes the responsibility to triage necessary inpatient days, for example, in the case of acute suicidality [1]. This requires a very networked and flexible way of working, taking into account the various players from the hospital, outpatient care and the patients’ social environment. The treatment is carried out according to a mutually agreed treatment plan, which after a few weeks also includes the initiation of a suitable follow-up solution, such as outpatient therapy. The treatment is carried out by a multi-professional and mobile team, which has a rapid operational readiness around the clock. Regular home visits are made, several times a day if needed. Depending on the problem, the home visit is made by a team member with the appropriate profession [2]. Table 1 summarizes the main organizational HT characteristics.

Delimitation

Unfortunately, the term HT is often used indistinctly both in research and in the implementation of services in practice, which makes a precise understanding of the concept difficult. The following section will therefore provide a brief overview of how HT can be conceptually distinguished from similar intermediary offerings.

Basically, HT can be differentiated from other community-based system interventions in terms of three treatment characteristics (mobility, team approach, acuity) [3]. HT outreach, for example, is clearly distinct from day hospitals, outpatient clinics, or “(Intensive) Case Management” (CM), which treat patients primarily in office settings and are not primarily outreach-based. In Switzerland, outreach (mobile) mental health services can be categorized into three groups [4]:

- Outpatient psychiatric care

- Mobile psychiatric services of hospitals and psychiatric clinics (consultation and liaison services as well as mobile units)

- Mobile services provided by other providers, such as live-in companionship

HT is based on a multiprofessional team approach and therefore differs significantly from monoprofessional services such as outpatient psychiatric nursing or physician consultation and liaison services. However, in addition to HT, there are other outreach mental health services that are multiprofessional in nature, such as Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) or Community Mental Health Teams (CMHT). The distinction from HT can be made here in terms of the degree of acuity of the disease phase and the duration of treatment. While HT offers patients in acute phases of illness an inpatient-equivalent alternative of limited duration, ACT and CMHT focus more on the rehabilitation of people with mental illness. These forms of long-term care are thus complementary to, and not primarily substitutes for, traditional inpatient treatment [4–6].

Effectiveness and advantages

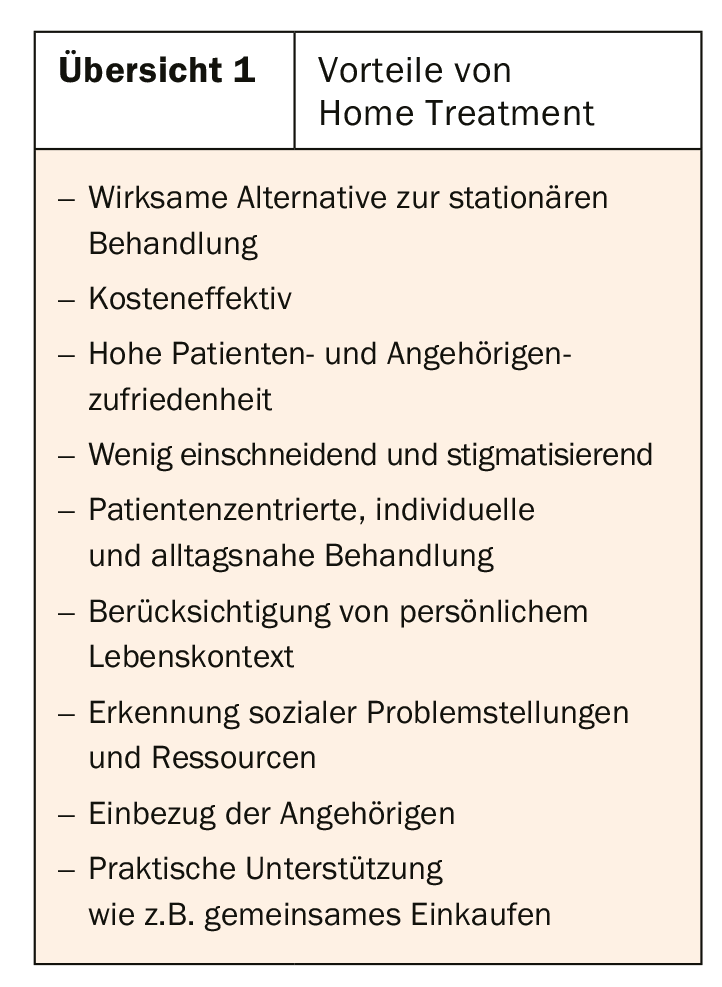

In the course of psychiatric deinstitutionalization, the introduction of various community-based care services for people with mental illness has been advocated, but their implementation status varies widely geographically [5]. While HT has been well established and evaluated in English-speaking countries, for example, the concept of HT in acute psychiatric care is only little known in German-speaking countries [7]. A legal basis for “ward-equivalent treatment” (StÄB) has existed in Germany since January 2018, as a result of which numerous pilot projects have been implemented since then [8]. The criteria for StÄB offerings are well defined and differ in some aspects from HT as designed in the offering presented here. HT is recommended as an alternative to acute inpatient treatment in the S3 guidelines “Psychosocial therapies for severe mental illness” with the highest level of evidence for routine treatment [3]. International and national studies have been able to demonstrate that the effectiveness of HT is no less than that of conventional residential treatments [9–11]. The results of these studies also showed that HT is likely to be more cost-effective, reduce burden on family members, and increase satisfaction with treatment services among both patients and their families compared with the inpatient setting. Furthermore, treatment in the home environment is often experienced by patients as less drastic and stigmatizing. The closeness to everyday life allows for individual treatment, whereby professional support can also take the form of practical help or skills training (e.g. shopping together, keeping the household tidy). The inclusion of the social environment is a matter of course in HT, but cooperation with the relatives must be well clarified at the beginning in order not to increase the stress situation [2,6] (overview 1).

However, the data available to date on specific impact factors in HT is very modest and further evaluation studies, especially from German-speaking countries, are urgently needed. In addition, little is known about HT-specific interventions. In contrast to the organizationally well-defined field of activity compared to other forms of care, the treatment content and therapies used in HT are still largely unexplored [7].

Limiting factors

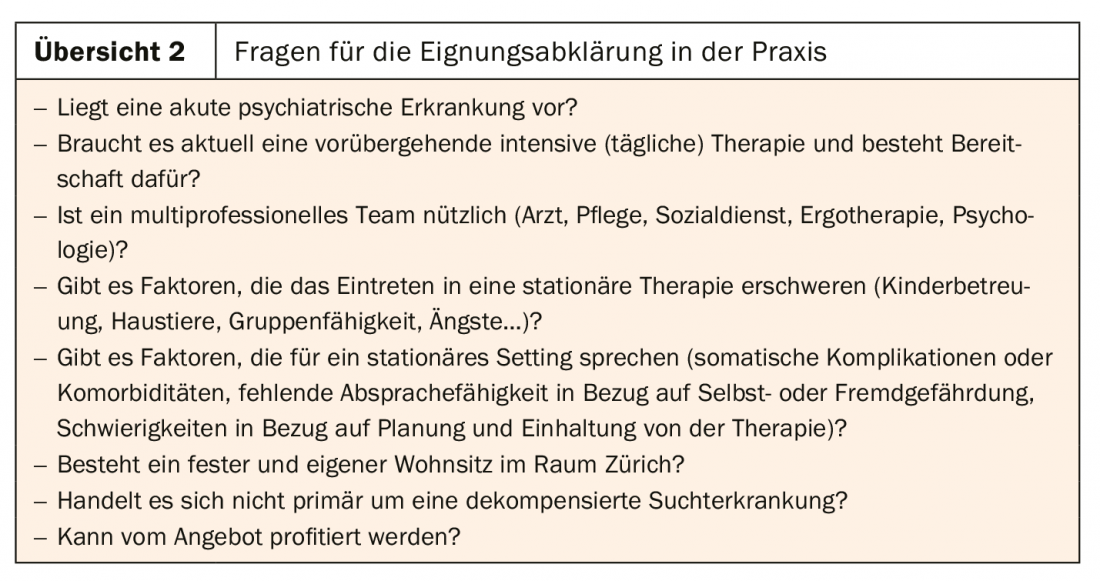

Inpatient stays cannot be replaced by HT in every case. Outreach treatment in the home environment is not suitable for persons with acute danger to others or themselves or in the case of acute intoxication or other medical emergencies. HT is also not very effective if there is a lack of consultation and cooperation (e.g., if the patient is out of the hospital at the time of the agreed appointments). If the goal of treatment is disorder-specific or primarily addiction cessation, HT is also less appropriate [2,6]. For patients with high somatic care requirements or somatic complications, or when the main focus is on rapid diagnosis, an inpatient stay is often more appropriate. Likewise, patients must have a certain commitment to planning therapy and keeping appointments.

In principle, it is recommended to perform a suitability assessment before admission to HT, which should always take into account the patient’s preferences and family situation in addition to the patient’s history, disease phase, and risk aspects [2]. Overview 2 summarizes possible guiding questions for the suitability assessment. Additionally, organizational factors, such as current workload, play a role in whether HT entry can occur. Organizational factors such as networked working practices, mobility and rapid accessibility, and a longer-term funding base were identified as key success factors [4]. However, the latter is often not the case for HTs in Switzerland, which is a key limiting factor for the planning security and further development of such offerings.

Insight into HT Zurich – Organization

In April 2016, the Home Treatment department opened as part of the Center for Acute Psychiatric Illness at PUK. Since then, full inpatient therapy has been available for 18 patients with acute psychiatric illness, ages 18-65. The prerequisite is to have a fixed and own residence in the Zurich area or the surrounding communities. To provide care 24 hours a day, seven days a week, a 15-member treatment team consisting of nurses, physicians, a psychologist, an occupational therapist and a social work staff member is available (Fig. 1).

Patients who meet the inclusion criteria have the opportunity to receive intensive multiprofessional treatment in the home setting for a limited time. Treatment includes at least one daily home visit, provided primarily by nursing, but also twice weekly by medical staff. In acute crises, the frequency can be increased to several home visits a day. Occupational therapy as well as social work are called in as needed and integrated into the patient’s weekly home visit schedule. Psychology can provide case management for individual patients as well as conduct testing or develop exposure plans. In order to maintain an overview in this complex planning with decentralized working methods, the team is actively supported by a team assistant (MPA). This ensures that the various resources are used optimally and that cooperation between the different professional groups runs as smoothly as possible. In addition to effective documentation, the brief daily team meeting to discuss all patient contacts is essential to staying on the same page therapeutically. In addition, the weekly therapy goals formulated together with the patients are written down and printed out for all involved specialists. These allow for a good reference as to where you are in your individual treatment planning. Important messages from the on-call team, as well as organizational and scheduling adjustments, are discussed each morning at the 5-minute meeting before the team leaves for home visits.

And with success! Since opening, more than 440 treatments have been completed. On the one hand, the scientific accompanying evaluation showed that the patient collective is comparable to that from the inpatient sector with regard to diagnoses and severity of illness. On the other hand, it also showed that HT is equally effective as inpatient treatment in terms of clinical treatment parameters such as symptom reduction, functional level, and readmission rates [9]. In addition to the high quality of treatment, the satisfaction of patients and their relatives is also very high, which shows appreciation for the HT team and makes it easier to work in constantly changing environments and sometimes difficult traffic conditions.

Implementation step by step

Despite the successful implementation of HT in the Swiss healthcare landscape, there are major uncertainties regarding the sustainable financing of the service. Although HT can be offered at a significantly lower cost than inpatient therapy, it has not been possible to negotiate a contract for a per diem rate with all health insurers. Thus, direct admission without prior cost approval is unfortunately only available to slightly more than half of all insured persons. However, we are optimistic that, due to the good success and the increasing level of awareness, an agreement can soon be reached for all insured persons. The experience gathered so far suggests that the still somewhat unfamiliar English term will soon be part of the standard repertoire of good psychiatric care.

Take-Home Messages

- Home Treatment is an evidence-based alternative to inpatient treatment for people with mental health problems in acute phases of illness.

- Mobile and multiprofessional teams with 24h availability treat patients at home in their familiar environment.

- Home Treatment is not indicated in cases of acute danger to others or oneself, or in cases of intoxication.

- By working in the immediate living environment, longer-term solutions to problems in coping with everyday life and in the social environment can be developed.

- Home Treatment is cost effective.

Literature:

- Johnson S: Crisis resolution and intensive home treatment teams. Psychiatry 2004; 3(9): 22-25.

- Gühne U, et al: Acute treatment in the home setting: systematic review and implementation status in Germany. Psychiatric Practice 2011; 38(03): 114-122.

- DGPPN: S3 Practice Guidelines in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy., Heidelberg: Springer, 2013.

- Stocker D, et al: Success criteria of mobile services in psychiatry. Final report. Bern: Federal Office of Public Health, 2018.

- Berhe T, et al: “Home treatment” for mental illness. The Neurologist 2005; 76(7): 822-831.

- Hepp U, Stulz N: “Home treatment” for people with acute mental illness. The Neurologist 2017; 88(9): 983-988.

- Sjølie H, Karlsson B, Kim HS: Crisis resolution and home treatment: structure, process, and outcome. A literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2010; 17(10): 881-892.

- Längle G, Holzke M, Gottlob M: Caring for the mentally ill at home. Station Equivalent Treatment Manual. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2018.

- Mötteli S, et al: Utilization and Effectiveness of Home Treatment for People With Acute Severe Mental Illness: A Propensity-Score Matching Analysis of 19 Months of Observation. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 495.

- Murphy SM, et al: Crisis intervention for people with severe mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 12: CD001087.

- Stulz N, et al: Home treatment for acute medical healthcare: randomised controlled trial. Br 7 Psychiatry 2019; 1-8 [epub ahead of print].

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(3): 32-39.