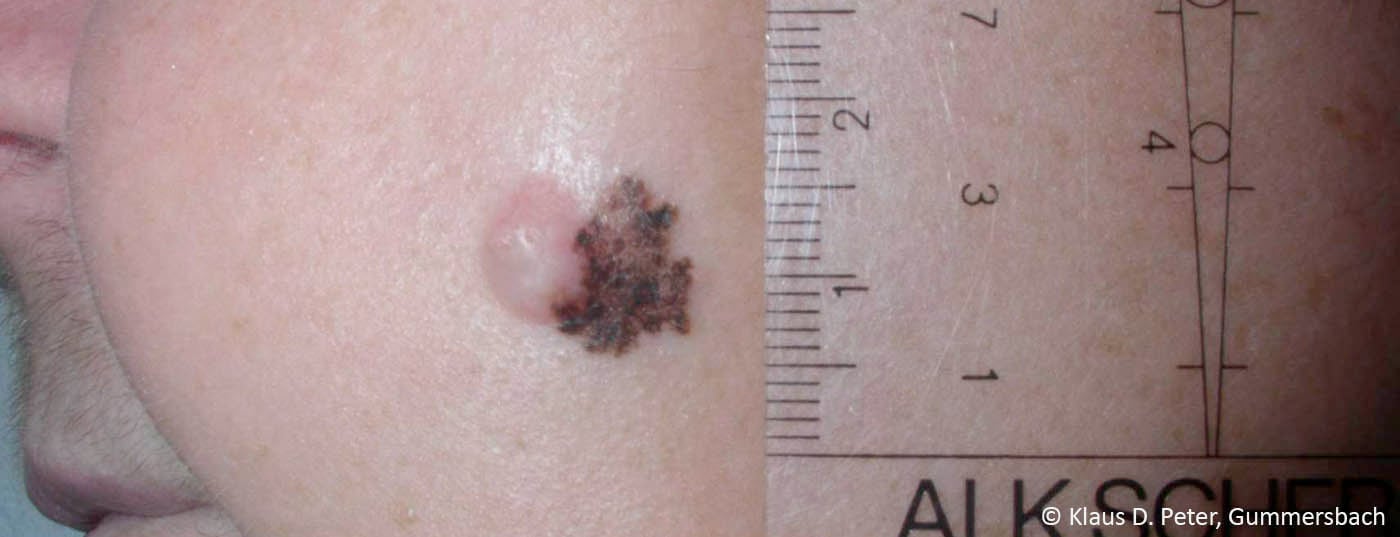

The use of targeted oncologics and immunotherapeutics has revolutionized the treatment of black skin cancer in recent years. However, the optimal therapeutic sequence remains unclear even today. A study analysis has now addressed the question of whether BRAF V600E/K mutation status has an impact on the success of immunotherapy in advanced malignant melanoma.

Approximately 40% of all metastatic melanomas have a BRAF mutation, with the activating BRAF V600E/K mutation being by far the most common [1]. This genetic alteration may be of therapeutic benefit and serves as a target for various targeted treatments. For example, vemurafenib and encorafenib are mutation-specific BRAF inhibitors that are highly valued in melanoma therapy. Combination with MEK inhibitors such as trametinib can further increase the efficacy of these agents and result in less secondary resistance. MEK, like BRAF, is a component of the MAPK signaling pathway, which is important in pathogenesis and whose uncontrolled activation in BRAF-mutated melanoma leads to excessive cell growth [2]. In addition to targeted agents for BRAF and MEK inhibition, immunotherapeutics are also used in the treatment of metastatic black skin cancer [3]. With the multitude of options, the question of the optimal therapeutic sequence to maximize efficacy and tolerability also arises. Data to date suggest that response to first-line therapy is better than to all subsequent treatments, regardless of whether primary checkpoint or BRAF/MEK inhibitors are used [4].

Evaluation of immunotherapy after targeted therapy.

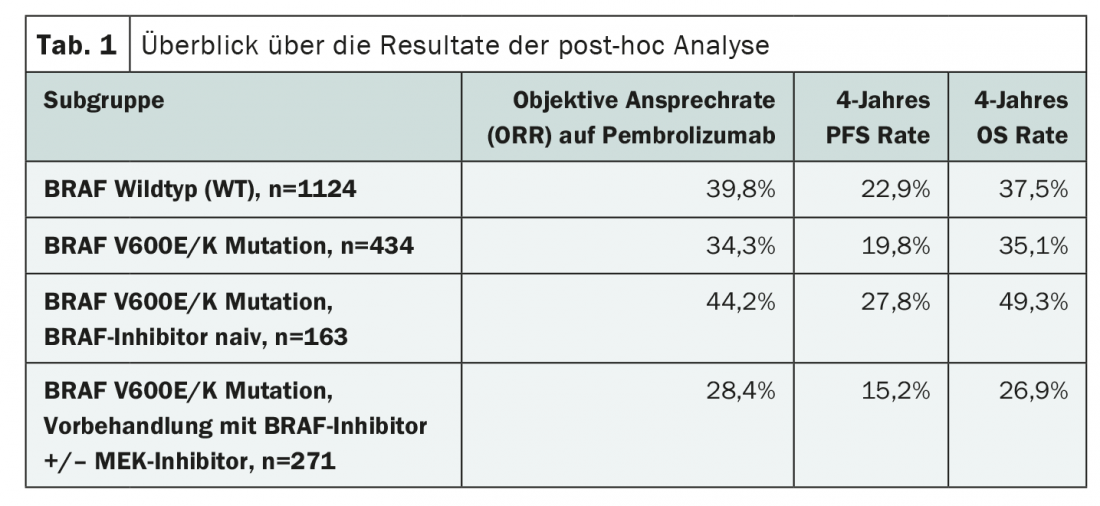

Further evidence on the potential interaction of targeted therapies and checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of malignant melanoma is now provided by a study recently published in JAMA Oncology. The authors investigated the impact of BRAF mutation status and prior BRAF/MEK inhibition treatment on immunotherapy with the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab. To do so, they analyzed data from three randomized clinical trials, KEYNOTE-001, KEYNOTE-002, and KEYNOTE-006. The analysis included 1558 adult patients with advanced melanoma whose BRAFV600E/K mutation status was known and who received pembrolizumab. 1124 patients had BRAF wild type (WT) and 434 patients had a BRAF mutation, which had been targeted in 271 cases. Primary endpoints of the retrospective analysis were objective response rate (ORR) to pembrolizumab, and PFS and OS rates at four years on immunotherapy (Tab.1). On the one hand, outcomes were compared in sufferers with BRAF WT and mutant BRAF status, and on the other hand, the authors also evaluated the effects of BRAF inhibitor therapy with or without additional MEK inhibition within the subgroup of patients whose tumor had a BRAF mutation.

When comparing BRAF WT and BRAF mutated tumors, slightly better results were seen in those without the mutation (Table 1). However, the majority of patients with BRAF mutation had received prior therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors. In addition, they were older on average and had more frequently already undergone treatment with ipilimumab.

Comparison of subgroups with and without BRAF inhibitor treatment suggested that appropriate pretreatment was a poor prerequisite for immunotherapy (Table 1). However, closer examination revealed that those patients who were pretreated with targeted therapy generally had poorer outcomes. For example, there was a higher number of PD-L1 negative tumors and brain metastases among them. Nevertheless, a certain effect remained in various subgroup analyses, which, however, according to the authors could be due to weaknesses in the patient selection of the study.

With regard to safety, neither mutation status nor pretreatment with BRAF inhibitors seemed to play a role. Adverse drug reactions were evenly distributed across all patients. The authors concluded that the use of pembrolizumab can provide clinical benefit in all subgroups studied and that safety is assured even with pretreatment. To confirm these statements, to possibly prove a significant effect of BRAF inhibitor therapy on subsequent lines of treatment, or even to be able to recommend a therapy sequence, much research is probably still needed, also in the context of prospective studies. Although much has already been done with the development of various new substances, which have already sustainably improved the prognosis in malignant melanoma, further milestones in the management of black skin cancer could be achieved with their optimal use and subgroup-specific treatment.

Source: Puzanov, et al: Association of BRAF V600E/K Mutation Status and Prior BRAF/MEK Inhibition With Pembrolizumab Outcomes in Advanced Melanoma: Pooled Analysis of 3 Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6(8): 1256-1264.

Literature:

- Long GV, et al: Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(10): 1239-1246.

- Knispel S, et al: Malignant melanoma: options for advanced stage patients. Dtsch Arztebl International 2018; 115(20-21): 4-9.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN clinical practice guidelines: cutaneous melanoma (version 4.2020). www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf.

- Johnson DB, et al: Sequencing Treatment in BRAFV600 Mutant Melanoma: Anti-PD-1 Before and After BRAF Inhibition. J Immunother 2017; 40(1): 31-35.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2020; 8(6): 30.