Sore throat is usually harmless and self-limiting. Sometimes, however, streptococcal angina is behind it, which is readily treated with antibiosis. However, this usually shows no advantages at all.

Sore throat is a common reason for consultation in family practice and of high socioeconomic importance. As a rule, sore throats are self-limiting and of viral etiology. In children aged 5-16 years, 70% of sore throats are viral in nature and in adults even in more than 80% [1,2]. Only about 20-30% of children and 5-15% of adults with sore throat have streptococcal angina [3]. So-called streptococcal angina is a bacterial acute tonsillitis and is caused by β-hemolytic group A streptococci. Pathogens of viral acute tonsillitis include influenza, parainfluenza, rhino, adenovirus, enterovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Infection occurs via droplet infection. In the German-speaking world, terms such as acute tonsillitis, acute pharyngitis and acute tonsillopharyngitis are sometimes used synonymously.

Studies from Denmark, Spain, USA, and Belgium have shown that 45-84% of patients with sore throat receive antibiotic treatment regardless of viral or bacterial etiology [4]. Guidelines from the Netherlands, UK, Germany, and Scotland have long advocated a more restrictive prescription of antibiotics for sore throat, as they show no effect in viral etiology and only marginal symptom improvement in streptococcal angina [1,5–7]. Thus, the duration of symptoms with antibiotic therapy in the case of streptococcal angina is shortened by just one day [5]. According to European guidelines, prevention of rheumatic fever, peritonsillar abscess, or glomerulonephritis are no longer indications for antibiotic therapy [5]. The risk of glomerulonephritis was not reduced in English studies despite the use of antibiotics, and the incidence of rheumatic fever has been declining sharply in Europe for many years, a trend that predates antibiotic therapy [8]. Improved socioeconomic conditions are thought to have been a major contributor, and antibiotic therapy was only of minor importance in this regard.

Thanks to a more restrictive use of antibiotics, the side effects of unnecessary antibiotic therapies can be avoided. In addition, antibiotics alter the microbiome, which in turn can lead to Clostridium difficile colonization, but also to reduced host immunity in general [9]. In addition, frequent use of antibiotics leads to increased resistance. As mentioned in the recently published article “Treatment of Streptococcal Angina” [10], the course of uncomplicated streptococcal angina with or without antibiotics differs only marginally from each other. In addition, purulent complications or rheumatic fever cannot be prevented by antibiotics. It is more important to educate the patient about the usually harmless and self-limiting course of the disease, provide adequate analgesic treatment, and advise the patient to check back in after 2-3 days if there is no improvement.

Clinic

The leading symptom of acute tonsillitis, regardless of the genesis, is sore throat and especially pain on swallowing. These are often accompanied by general symptoms such as a general feeling of illness, reduced general condition and fever. High fever and ductal enlargement of the angular cervical lymph nodes are more suggestive of a bacterial etiology, whereas catarrhal symptoms such as rhinorrhea, cough, and hoarseness are more suggestive of a viral etiology. Streptococcal angina typically presents on inspection of the pharynx with reddened palatine tonsils on both sides with the stippling and lacunae described in textbooks. However, these typical findings are not always present and, on the other hand, inspection of the pharynx is not always adequately possible, especially in children. Acute viral tonsillopharyngitis usually shows only reddened tonsils usually without stippling and redness of the posterior pharyngeal wall. Prolonged courses and unilateral complaints are atypical; in such cases, other differential diagnoses must be considered.

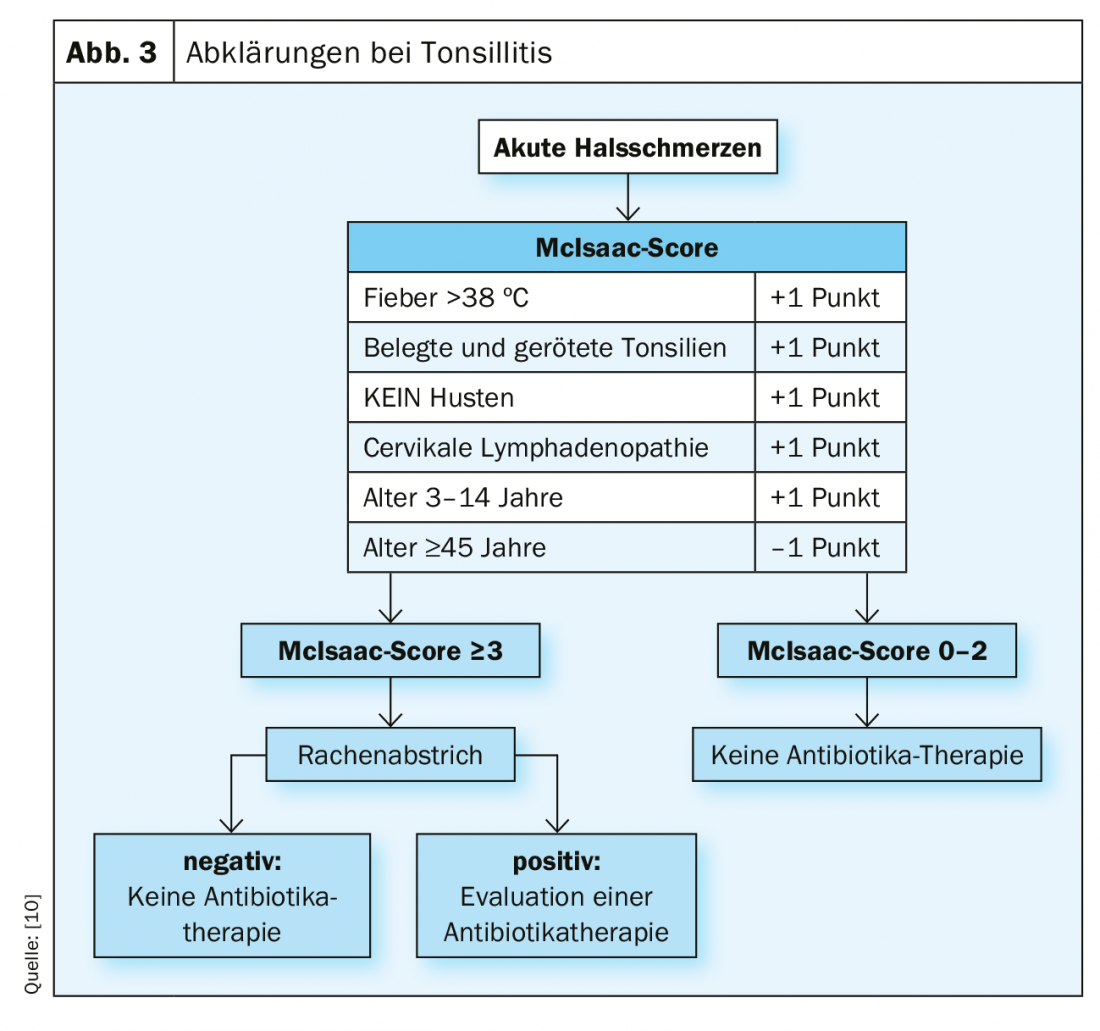

The Centor and McIsaac scores were developed and validated years ago to assess the risk of bacterial genesis [11], although even with these criteria, viral genesis cannot always be clearly distinguished from bacterial genesis.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of acute tonsillitis is made by a careful history, inspection of the pharynx, and palpation of the cervical lymph node stations. The Centor score (validated only for adults) or its modification, the McIsaac score, which can already be used in children, give the probability that the patient has streptococcal angina. From a score ≥3, the probability is between 28-35%. In the McIsaac score, children younger than 15 years of age receive an additional point in the scoring because the peak of disease in streptococcal angina is in this age range [8].

A McIsaac score between 0-2 does not require a throat swab with rapid strep test, as the probability of strep throat is only 0-17%. For throat swabs in children, it is always important to remember that up to 10% of children are asymptomatic streptococcus carriers [12]. With a McIsaac score of >3 , the increased risk justifies a throat swab, although with regard to antibiotic therapy, a wait-and-see approach also makes sense here [12].

If a wait-and-see approach is chosen, it is important to ensure that the patient does not present with any so-called red flags that may require immediate antibiotic therapy [10]. Red flags are: Immunosuppression, unusual course, findings strictly unilateral, severe pain in the neck on touch, lockjaw, significant comorbidities, poor general condition.

The rapid streptococcal test has a specificity of around 95% when performed correctly. The negative predictive value is between 93-97% and sensitivity around 86-95% compared to culture [5]. It is important to take the swab specifically in the area of infection, e.g. the palatine tonsils, with the mouth wide open and the tongue depressed, and to swab several times. If gagging occurs, a numbing spray (e.g., xylocaine) may be helpful. The result is then available within minutes. A routine control smear in the further course is not necessary. Cultures are usually no longer recommended. Laboratory analysis (leukocytes, CRP, antistreptolysin titer) is primarily not recommended, as these values are not relevant for a therapeutic decision or differentiation between viral and bacterial infection [1,13].

Therapy

With a McIsaac score between 0-2, primary symptomatic therapy is recommended. NSAIDs and acetaminophen are extremely effective, and patients should also be urged to drink enough and take physical rest, especially in the presence of fever [5,10]. Throat compresses and topical disinfectant and analgesic therapy in the form of lozenges or mouth rinses may provide additional relief [7].

If the McIsaac score is ≥3 and the throat swab is negative, symptomatic therapy is also given. The current paradigm shift in the treatment of streptococcal angina is now that even with a McIsaac score >3 and positive throat swab, treatment is also symptomatic and not antibiotic. Delayed antibiotic therapy is indicated only in the absence of improvement of symptoms after 48-72 hours. Immediate antibiotic therapy may be considered for high-risk patients with Red Flags [10]. Antibiotic of choice is penicillin V 1 million E/12h per os, although 6 days is usually sufficient [12]. Amoxicillin, which is also available as a syrup for children, may be prescribed as an alternative (25 mg/kg/12h). For penicillin allergy without anaphylaxis, cefuroxime 500 mg/12h is recommended instead, or for penicillin allergy with anaphylaxis, clarithromycin 500 mg/12h.

Patients at risk include young children, patients >65 years of age, patients with significant underlying diseases or comorbidities (immunocompromised, rheumatic fever in self or family history), or patients in significantly reduced general condition [7,10]. Unilateral pain, trismus, or unilateral pressured edema of the neck are signs of a complication (abscess) and should be further evaluated by a specialist.

Open and detailed communication with patients or parents is critical for successful implementation of the latest recommendations. A corresponding communication strategy has also been published [10]. Patients are informed of expected symptom duration, options for symptom relief, and reasons for not using antibiotics. In addition, the patient is given reassurance with the offer of follow-up care by telephone or by means of a new consultation.

Differential diagnostics

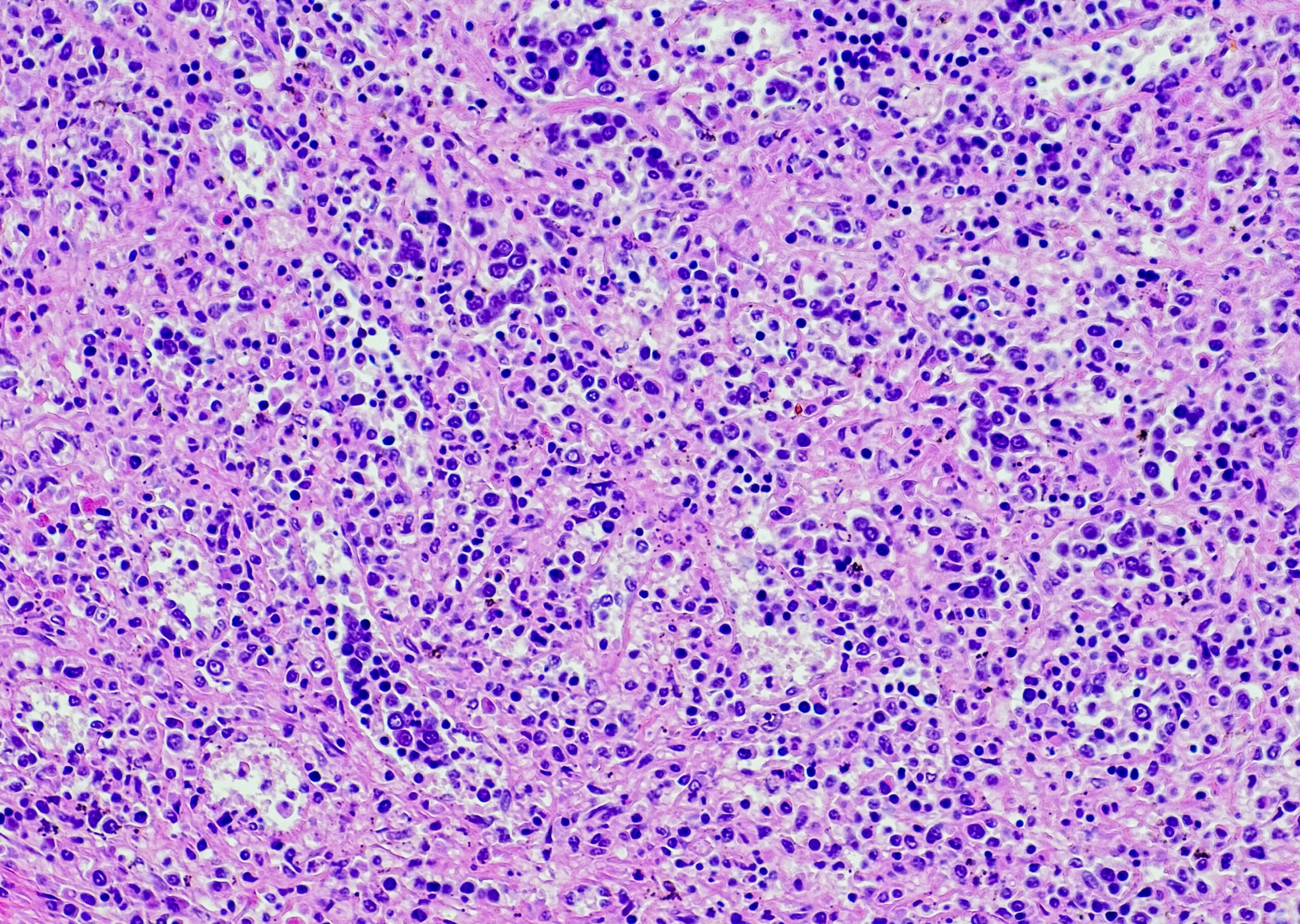

Infectious mononucleosis: Infection with EBV usually occurs in childhood, in Western countries more likely in adolescence. Over 98% of those over 40 are carriers of the virus. Patients have severe sore throat and are febrile. Clinically, there are grayish-white smeary tonsils and marked bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, especially of the nuchal lymph nodes, and often hepato-, splenomegaly. Laboratory findings include an increase in transaminases and lymphocytosis. The lymphocyte/leukocyte ratio (absolute values) is >0.3. Serology is part of the definitive diagnosis. Purely symptomatic therapy is used.

Scarlet fever: Scarlet fever is also a streptococcal disease mediated by streptococcal exotoxins. Patients typically complain of fever, headache and sore throat. The pharynx and tonsils are reddened, and coatings may appear on the tonsils as the disease progresses. At the beginning, the tongue has a whitish coating; after a few days, this coating detaches and the lingual papillae become prominent (“raspberry tongue”). Patients often develop exanthema after a few days (axillae and groin preferred), but the mouth-chin triangle remains absent. Scarlet fever responds well to penicillin therapy.

Herpangina: This is caused by the Coxsackie A virus. Patients typically have vesicles in the mucosa of the palate and tonsils and fibrin-covered ulcers as they progress. Therapy is always symptomatic.

Peritonsillar abscess: these patients usually present with unilateral severe throat and swallowing pain, and sometimes have a diarrhea-like speech. Clinically, there is a lockjaw as well as a bulging palatal arch and a swollen uvula that is deviated to the opposite side. The cause is often streptococci and anaerobes. 2/3 of all peritonsillar abscesses occur in individuals who have a prior McIsaac score of 0-2 or who had no prior sore throat [14]. Moreover, the peak age of peritonsillar abscess is in young adults, in contrast to streptococcal angina, which occurs mainly in young children [7]. Currently, there is controversy as to whether peritonsillar abscess is actually a complication of streptococcal angina or a separate clinical picture. Therapy of choice is decompression of the abscess followed by antibiotic therapy. If peritonsillar abscess is suspected, the patient should be referred to an ORL specialist.

Plaut-Vincent angina: This is a rare form of tonsillitis caused by an infection with Treponema vincenti and Fusobacteria. Mostly afebrile, patients present with unilateral ulcerative change of the tonsil and moderate, typically unilateral, sore throat in good general condition. Therapy of choice is penicillin.

Evidence base

Despite antibiotic therapy, the symptom duration of streptococcal angina is shortened by only one day, and even with antibiotic therapy, rheumatic fever, glomerulonephritis, or peritonsillar abscess cannot be prevented [5]. No increase in peritonsillar abscesses has been demonstrated in England despite a decrease in antibiotic therapy in children [14]. If there is no improvement, antibiotic therapy can be started after a delay [5,10]. This approach allows to prevent unnecessary antibiotic administration and to select patients with the need for antibiotic therapy.

Patient satisfaction is not dependent on antibiotic therapy. More important is an empathetic doctor-patient conversation. The patient should feel taken seriously and understand the therapy concept. He should be able to understand that in the presence of streptococcal angina, antibiotics can shorten symptom duration by as little as one day, but potentially have side effects. Also, without antibiotics, there is no fear of increased complications or prolonged absences from work, school [3].

Take-Home Messages

- With or without antibiotics, streptococcal angina usually has a harmless, self-limiting course and heals within a week. Even without antibiotic therapy, there is no increase in absenteeism from school or work [13].

- Antibiotics reduce the symptom duration of streptococcal angina by only one day. The risk of complications is not increased even without antibiotic therapy. Thus, the benefits of antibiotic therapy are small and advantages must be carefully weighed against disadvantages.

- From a McIsaac score ≥3, a throat swab may be performed if it is relevant to the decision. If the result is positive, pain-relieving therapy can also be tried first and antibiotic therapy can only be started after a delay if there is no response.

- If antibiotic therapy is indicated, penicillin or amoxicillin are the therapy of choice. Good patient education, empathy

- and empathy are crucial. This ensures that the patient understands the therapy concept and will contact you again if there is no improvement.

Literature:

- Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB: Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd 2013; 139(11): CD000023.

- Wessels MR: Clinical Practice. Streptococcal pharyngitis. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(7): 648-655.

- Bisno AL, et al: Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infect Dis 2002.

- Reinholdt K, et al: Management of sore throat in Danish general practices. BMC Family Practice 2019; 20: 75.

- ESCMID Sore Throat Guideline Group, Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L et al. Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012; 1-28.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: Management of sore throat and indication for tonsillectomy 2010: www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign117.pdf

- Wächtler H, et al: The Neck Pain Guideline of the German Society for General and Family Medicine. ENT 2011.

- Goslings WRO, Valkenburg HA, Bots AW, Lorrier JC: Attack Rates of Streptococcal Pharyngitis, Rheumatic Fever and Glomerulonephritis in the General Population. N Engl J Med 1963; 268(13): 687-694.

- Ubeda C, Pamer EG: Antibiotics, microbiota, and immune defense. Trends Immunol. 2012; 33(9): 459-466.

- Hofmann Y, Berger H: Treatment of streptococcal angina. Swiss Med Forum. 2019; 19(2930): 481-488.

- Fine AM, et al: Large-Scale Validation of the Centor and McIsaac Scores to Predict Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis. Arch Intern Med. 2012 June 11; 172(11): 847-852.

- Altamimi S, et al: Short-term late-generation antibiotics versus longer term penicillin for acute streptococcal pharyngitis in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012.

- AWMF, Therapy of Inflammatory Diseases of the Palatine Tonsils-Tonsillitis-S2k-Guideline 017/024; Status 08/2015.

- Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FDR, et al: Predictors of suppurative complications for acute sore throat in primary care: prospective clinical cohort study. BMJ Publishing Group 2013; 347(nov25 3): 6867-6867.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(2): 4-7