It was a long way from the development of the first artificial heart valve in the 1960s to modern biological heart valves made from animal tissue. At least in Europe, the latter are now clearly on the upswing. Why?

In 1960, the young surgeon Albert Starr, together with the experienced engineer Lowell Edwards, developed the first artificial heart valve, which was successfully implanted shortly afterwards in a patient with severe heart failure. The woman survived the surgery, but died of a pulmonary embolism after the procedure. In the second patient in the same year, Dr. Starr’s artificial heart valve already resulted in a survival of ten years, with death ultimately coming due to an unexpected fall from a ladder.

Five years later, the first biological heart valve was implanted. This was the heart valve of a pig. Development continued until, in 1971, it was possible to operate on a heart valve made from the heart tissue of a cow, attached to an artificial ring. Finally, it was Alain Cribier who first used a catheter-based heart valve shortly after the turn of the millennium.

Today, mechanical and biological heart valves continue to coexist. There are various forms of mechanical prostheses, the most common being the so-called “double wings”. In contrast to their mechanical counterparts, biological heart valves are constructed from animal tissue (e.g., aortic valve leaflets from pigs, i.e., porcine valves, or bovine valves made from the pericardium of cattle). The question of which is the best heart valve is more important today than ever before. Not least because there are considerable differences in usage internationally. In this context, TAVI has also been competing for the favor of physicians and patients for several years. For the replacement of the diseased aortic valve, catheter interventional valve replacement is pursued here instead of open heart surgery with heart-lung machine. The valve is placed on the beating, fully functional heart, with the prosthesis fixed in a folded state at the tip of a catheter. Subsequent expansion presses the old narrowed aortic valve against the aortic wall.

Guidelines – Reality

The trend is clear: Biological valves are being operated on more and more frequently in clinical reality today. Especially in Europe. This is to the detriment of the mechanical flaps. In the United States, the “gray area” where mechanical or biological aortic valves are considered (between 60 and 70 years) remains larger. The biological aortic valve should generally be considered in this country from the age of 65 . On both continents, mechanical aortic valves are actually the first choice until 60 years [1]. The European guidelines are relatively clear on this point [2]:

- Consider bioprostheses (aortic valve) from age 65 or (mitral valve) from age 70. In addition, for patients with a shorter life expectancy than the expected valve life.

- Consider mechanical prostheses (aortic valve) under age 60 or (mitral valve) under age 65.

Nevertheless, in a large Californian patient population, implantations of biological prostheses also increased significantly in the USA between 1996 and 2013. Aortic valve replacement surgeries are becoming more common – those of the mitral valve less so. According to the study, biological prostheses have a higher risk of reoperation, whereas mechanical valves require oral anticoagulation and also lead to bleeding and thromboembolism more frequently [3].

According to observational studies, mortality is comparable in patients between 50 and 69 years of age, regardless of the type and location of the prosthesis [4,5]. However, some differences emerged in the California patient population:

- Compared with its mechanical counterpart, the biological aortic valve replacement showed poorer survival to 55 years, and the biological mitral valve replacement to 70 years. In the first case, stroke incidence was significantly lower in patients aged 45 to 54 years, and in the second case, in patients aged 50 to 69 years.

- Bleeding was significantly less frequent with biological aortic valves, and with corresponding mitral valves this was also true in patients between 50 and 79 years.

- Reoperation was required more frequently with the biological variant, especially in younger patients.

- The 30-day mortality for redo was 7.1% for biological aortic valves and 14% for mitral valves.

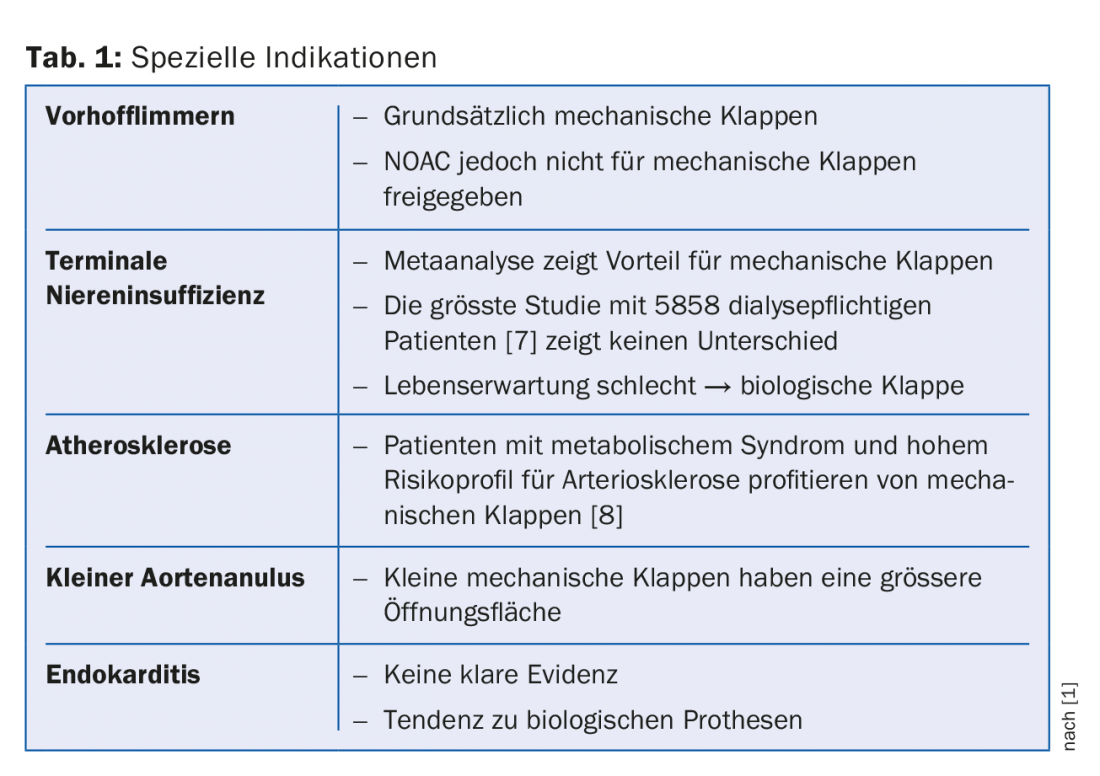

- “It can be concluded that the mechanical valve leads to better survival up to age 55 for aortic valve replacement, and up to age 70 for mitral valve replacement,” he said. In addition, special indications must be taken into account (Tab. 1).

Why not mechanical prostheses?

The reason why mechanical valves are being used less and less is probably due, on the one hand, to the good long-term results of their biological counterparts. Mention should be made, for example, of the data from Bourguignon et al. [6] on the biological Carpentier-Edwards PERIMOUNT aortic valve. Here, freedom from reoperation due to valve degeneration was shown to be approximately 71% and 38% at 15 and 20 years in the group up to 60 years of age, 83% and 60% in 60-70 year olds, and 98% in those even older. Over the two decades, the rate of valve-associated events was low, especially including structural valve degeneration. One flap lasted about 20 years across the cohort.

On the other hand, the upswing in catheter-based heart valves (TAVI) certainly plays a role. “There is much to be said for biological heart valves today,” Prof. Genoni summarized, “we have good long-term results and they do not require anticoagulation. Mechanical valves are considered when the patient absolutely does not want to waste any more thoughts on a possible heart operation or intervention. However, to avoid reoperation due to degeneration of a biological valve, TAVI can be used.”

Source: 16th Zurich Review Course in Clinical Cardiology, April 12-14, 2018, Zurich Oerlikon.

Literature:

- Head SJ, Çelik M, Kappetein AP: Mechanical versus bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J 2017 Jul 21; 38(28): 2183-2191.

- Falk V, et al: 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017 Oct 1; 52(4): 616-664.

- Goldstone AB, et al: Mechanical or Biologic Prostheses for Aortic-Valve and Mitral-Valve Replacement. N Engl J Med 2017 Nov 9; 377(19): 1847-1857.

- Chiang YP, et al: Survival and long-term outcomes following bioprosthetic vs mechanical aortic valve replacement in patients aged 50 to 69 years. JAMA 2014 Oct 1; 312(13): 1323-1329.

- Chikwe J, et al: Survival and outcomes following bioprosthetic vs mechanical mitral valve replacement in patients aged 50 to 69 years. JAMA 2015 Apr 14; 313(14): 1435-1442.

- Bourguignon T, et al: Very long-term outcomes of the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount valve in aortic position. Ann Thorac Surg 2015 Mar; 99(3): 831-837.

- Herzog CA, et al: Long-Term Survival of Dialysis Patients in the United States With Prosthetic Heart Valves. Circulation 2002; 105: 1336-1341.

- Lorusso R, et al: Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with faster degeneration of bioprosthetic valve: results from a propensity score-matched Italian multicenter study. Circulation 2012 Jan 31; 125(4): 604-614.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(5): 45-48

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(3): 35-36