Bullous autoimmune dermatoses represent a heterogeneous group of rare, sometimes severe autoimmune diseases, which include pemphigus and pemphigoid disorders, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and dermatitis herpetiformis Duhring. A common feature of bullous autoimmune dermatoses – with the exception of Duhring’s disease – are autoantibodies directed against structural proteins of the skin and mucous membranes and responsible for a loss of cutaneous integrity [1].

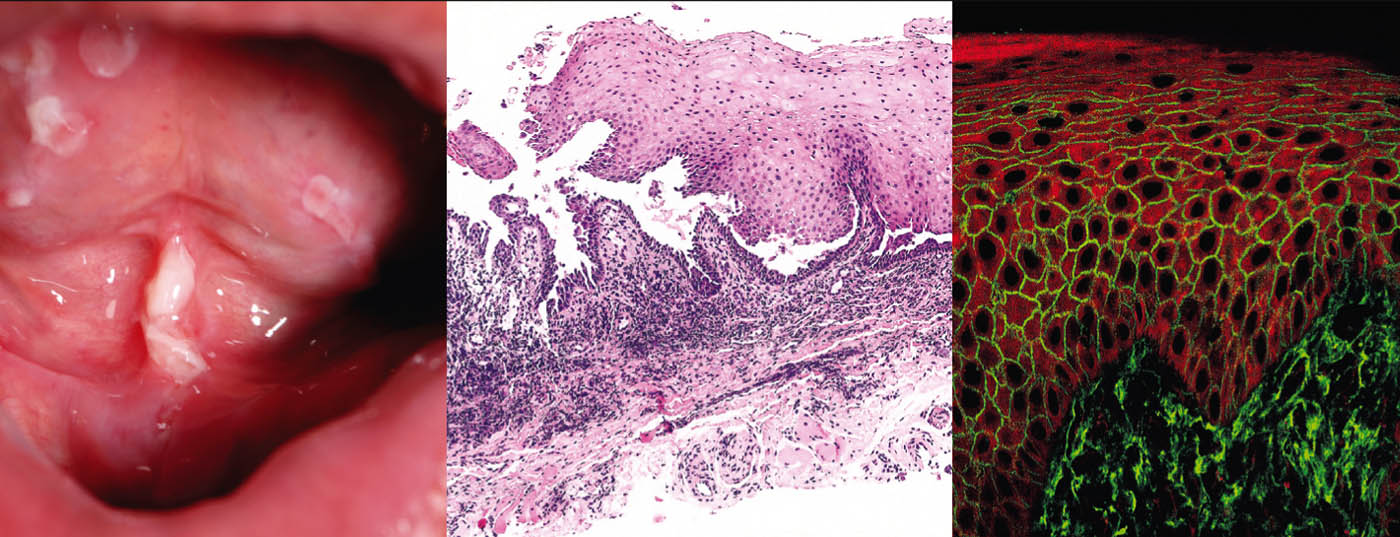

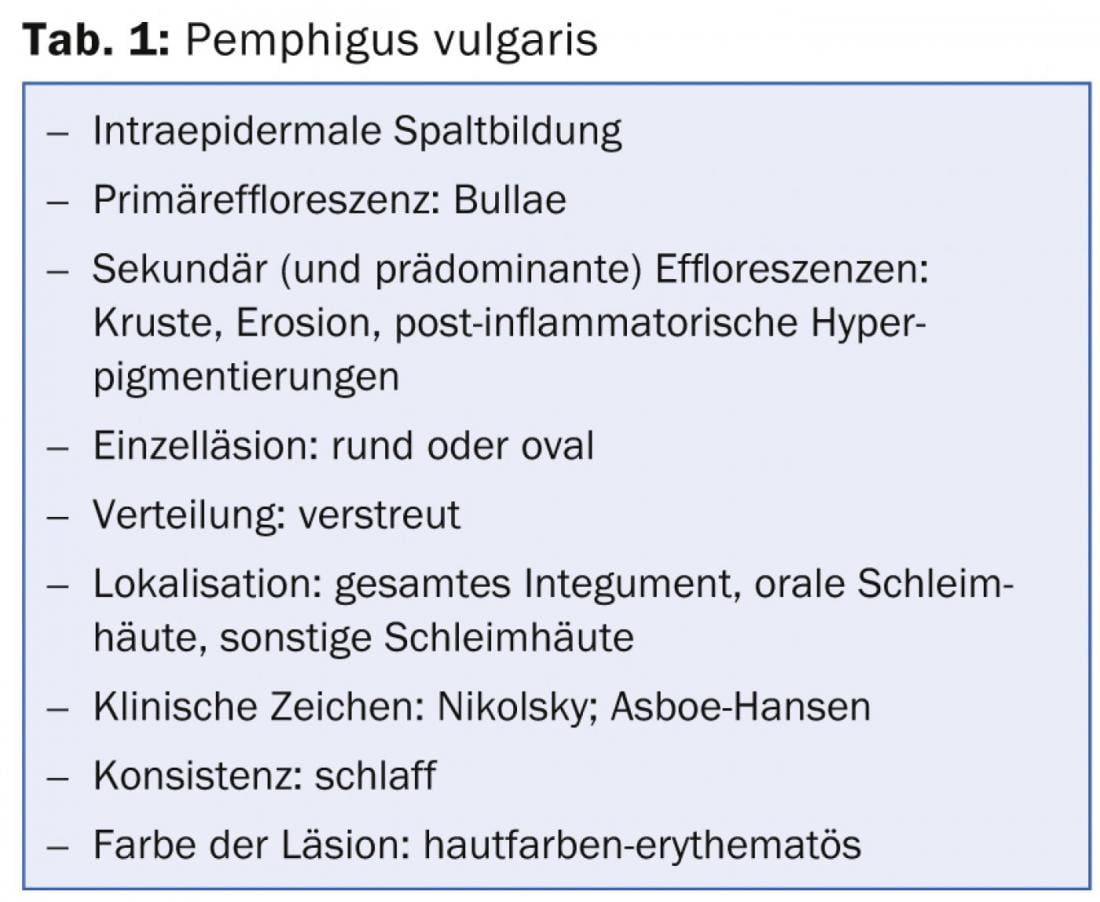

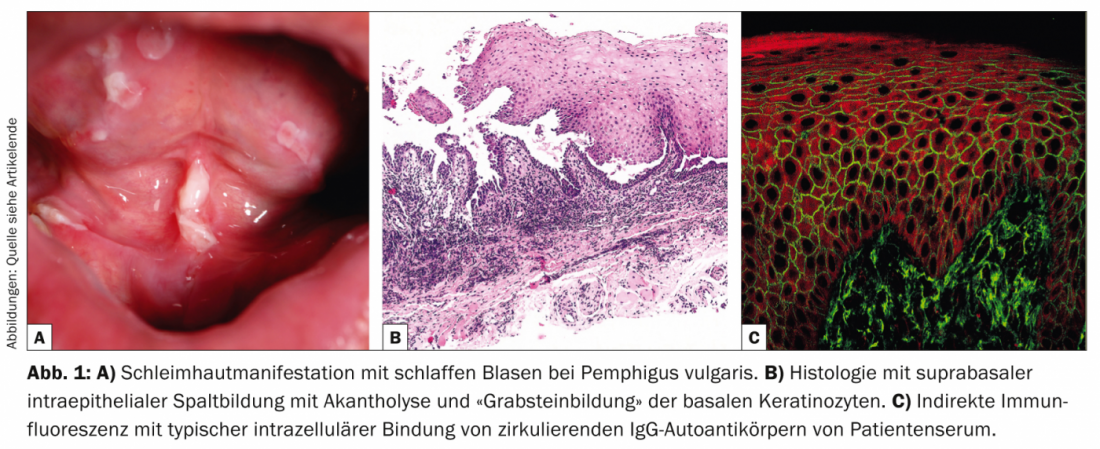

Pemphigus vulgaris (Table 1, Fig. 1) manifests with generalized, mucocutaneous, flaccid blisters that rupture very rapidly, so that the clinical picture is usually dominated by erosions and crusts.

Involvement of the mucous membranes, especially in the mouth, which is very painful, occurs in most patients and so the diagnosis is not infrequently made initially by dentists. Pathogenetically, pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by autoantibodies (AK) against cell adhesion proteins – desmogleins 1 and 3. In patients with exclusively oral infestation, AK are directed against desmoglein 3. Histopathologically, there is suprabasal intraepidermal cleft formation with acantholysis and “tombstone formation” of basal keratinocytes. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows typical intercellular IgG and C3 deposits in the epidermis. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) from patient serum confirmed circulating IgG autoantibodies. Using ELISA, direct detection of desmoglein 3 and desmoglein 1 can be achieved in patient serum [2].

Therapy is primarily aimed at reducing autoantibody production. Here, systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide or ciclosporin continue to be the standard therapies. Other options include plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG). In therapy-resistant cases, the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab in particular is a promising alternative. In addition to pemphigus vulgaris, the group of pemphigus diseases also includes pemphigus foliaceus [3], pemphigus herpetiformis [4], paraneoplastic pemphigus [5], and IgA pemphigus.

Bullous pemphigoid

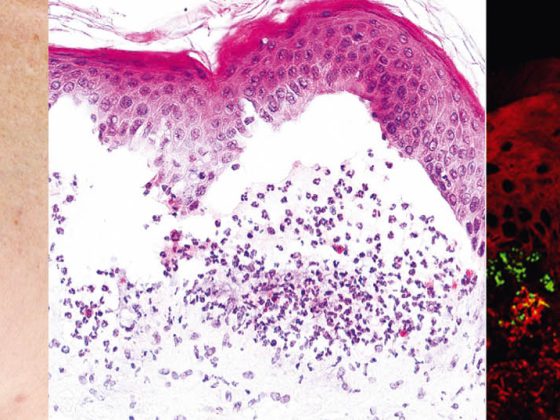

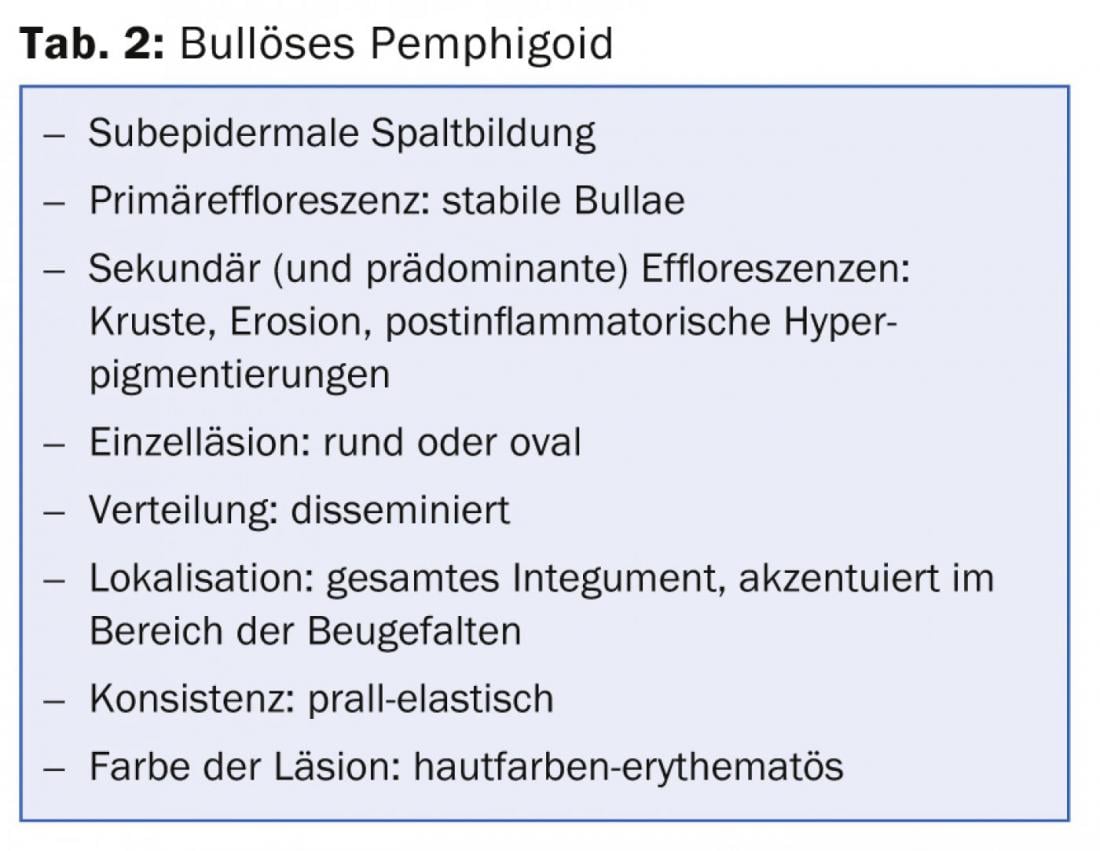

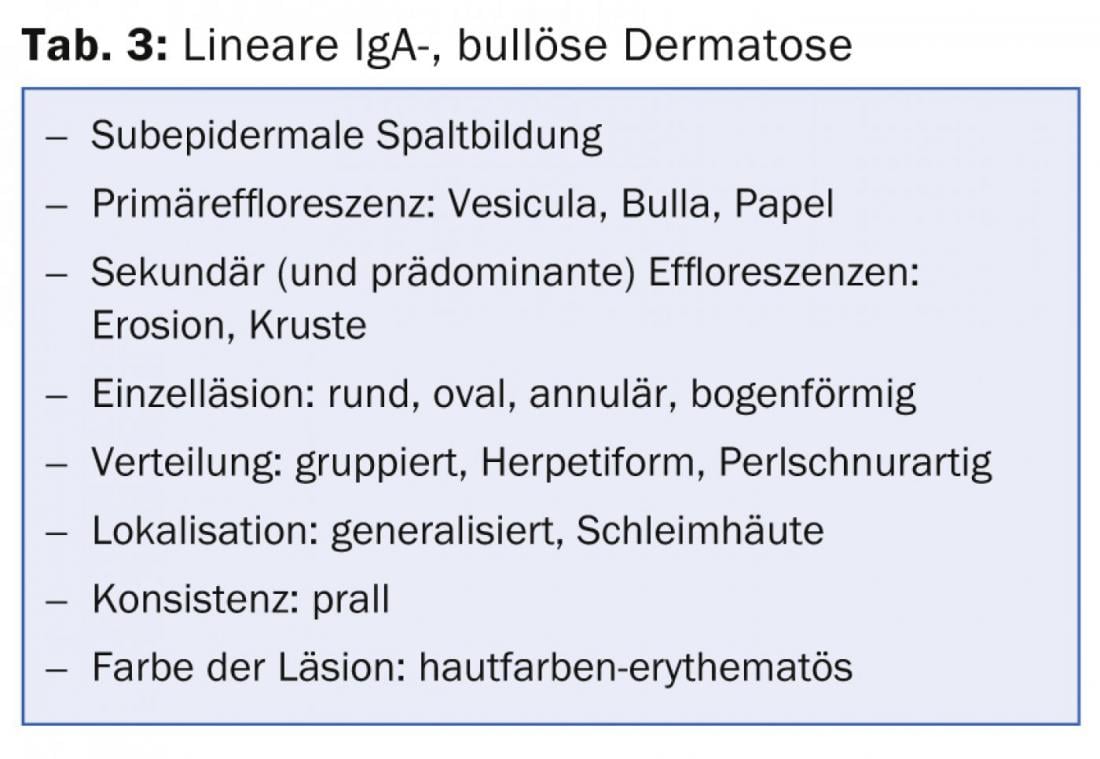

With an incidence of 12.1 new cases/million/year in Switzerland, bullous pemphigoid (Tab. 2, Fig. 2) is the most common disease from the pemphigoid group and also the most common blistering autoimmune dermatosis of all [6].

Bullous pemphigoid occurs mostly in old age and is characterized by bulging blisters on inflamed-reddened or normal skin that is intensely itchy. Often this disease initially progresses without blistering and is diagnosed as eczema, urticaria or prurigo due to the pronounced pruritus. Pathogenetically, the disease is due to autoantibodies against BP 180 (also known as type XVII collagen). Histology shows subepidermal blistering with intact epidermis and prominent eosinophil-rich infiltrates. In DIF from perilesional skin, IgG deposits are found along the dermal-epidermal junctional zone (basement membrane), which can be confirmed in IIF with the detection of IgG antibodies binding to the basement membrane. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity and can be determined during follow-up to determine the need for further therapy.

Topical or systemic corticosteroids remain the basis of therapy. Other options include tetracyclines with nicotinamides, dapsone, or immunosuppressants in severe disease, most notably azathioprine, and IVIG and rituximab in treatment-resistant cases.

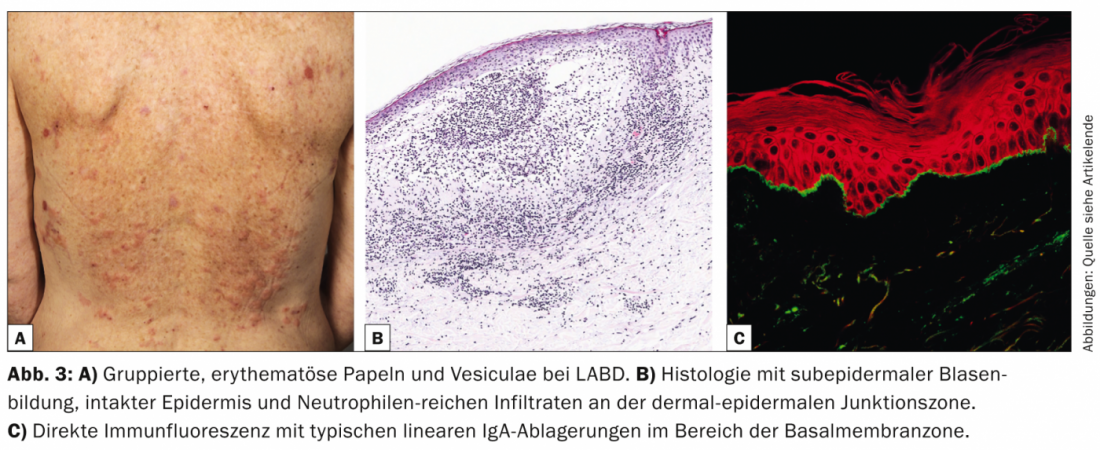

Linear IgA, bullous dermatosis

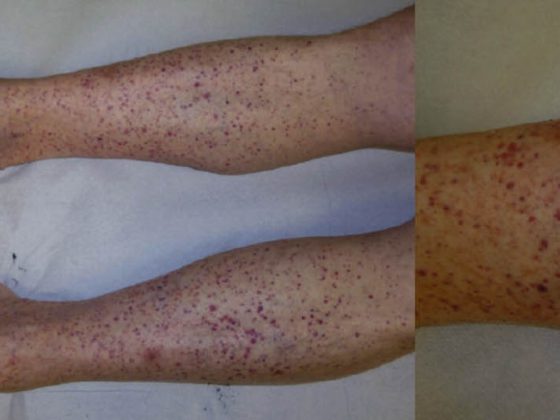

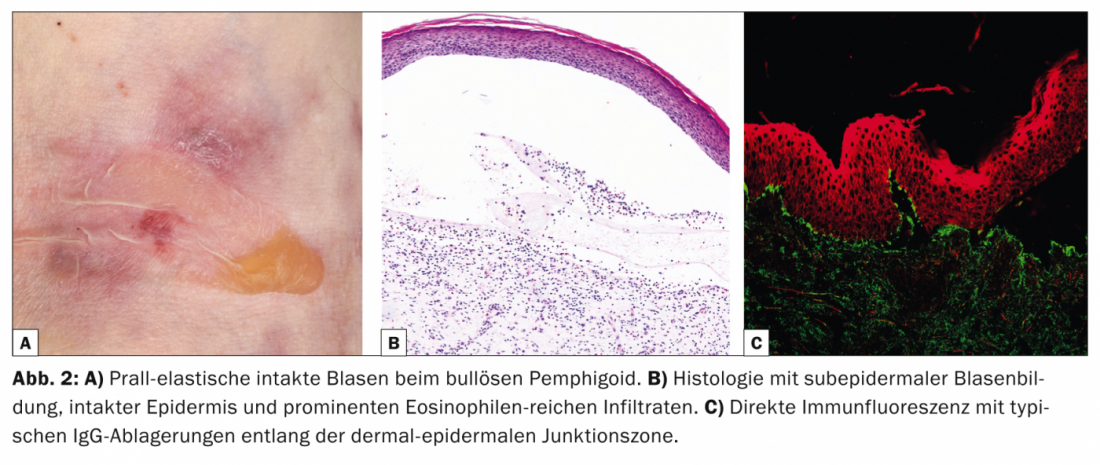

Linear IgA dermatosis (LABD, Tab. 3, Fig. 3) is characterized by pruritic, generalized, extensor-side accentuated vesicles and bullae. The disease occurs in both adults and children.

In childhood, it represents the most common bullous autoimmune dermatosis and is usually self-limiting [7]; in adults, LABD is often associated with drugs (vancomycin) [8]. Histologically, LABD is similar to Duhring’s disease in that it is characterized by subepidermal blistering, intact epidermis, and neutrophil-rich infiltrates at the dermal-epidermal junctional zone. DIF shows linear IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone.

IIF can confirm the diagnosis by detecting circulating IgA autoantibodies that bind to the bladder roof. The majority of patients respond to therapy with dapsone or sulfapyridines. Successful treatments have also been described in children and adults with various antibiotics (cicloxacillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole).

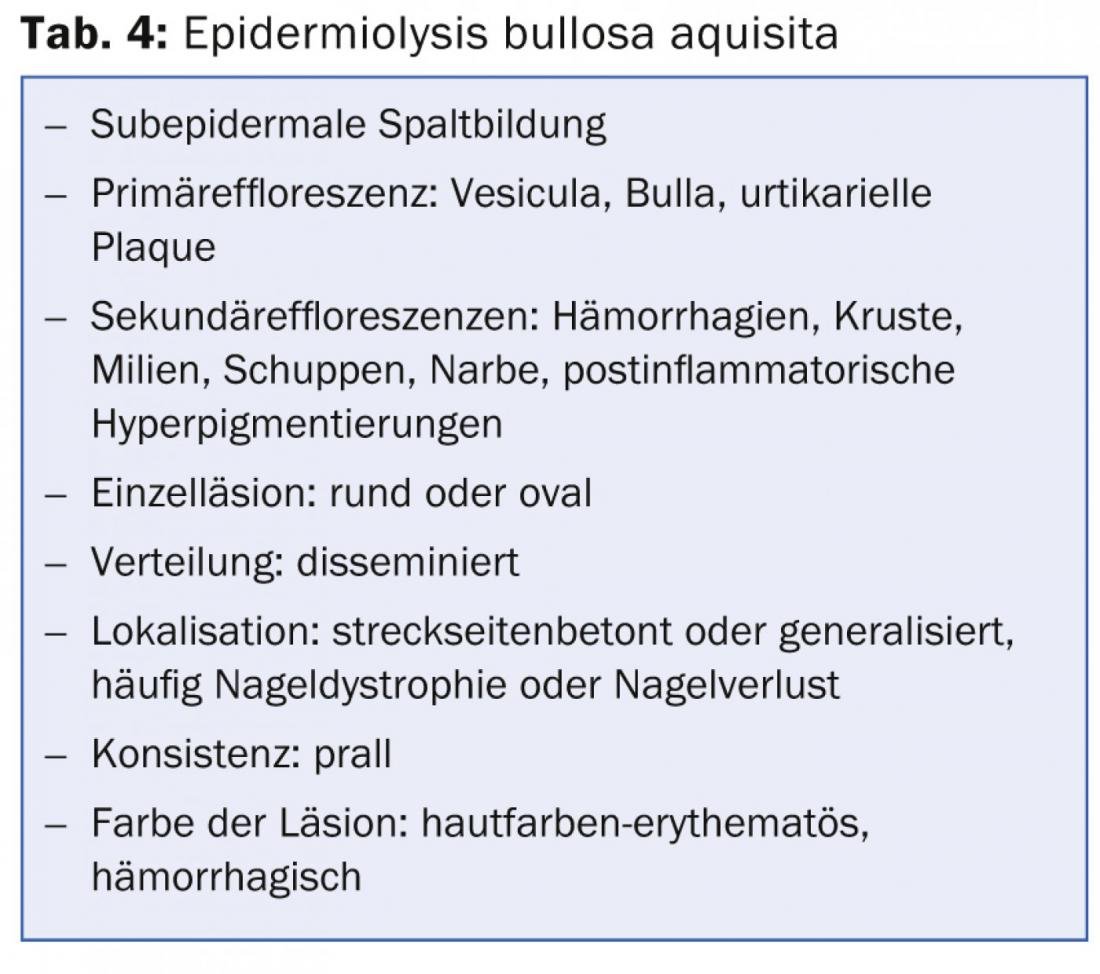

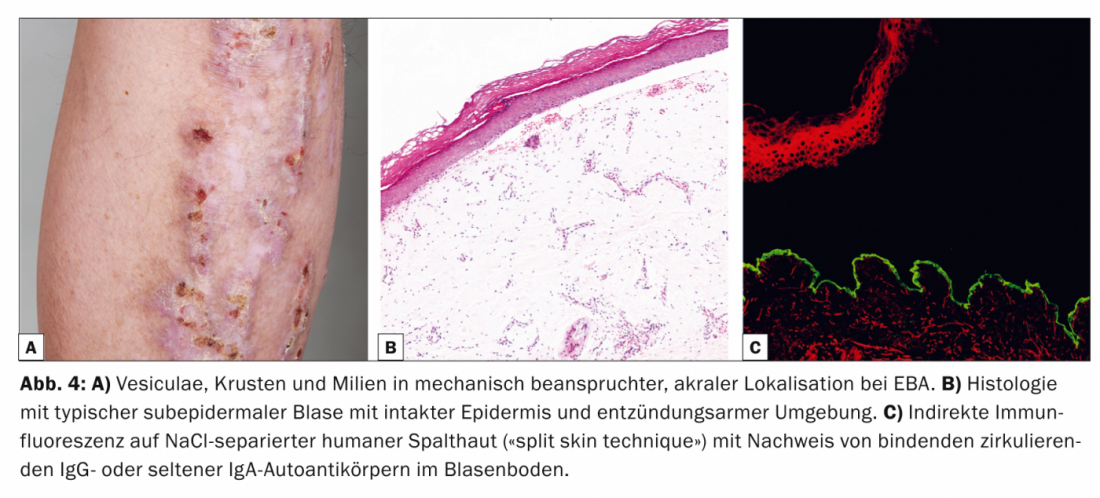

Epidermiolysis bullosa aquisita

Epidermiolysis bullosa aquisita (EBA, Table 4, Fig. 4) is divided clinically into a localized, often acrally accentuated, noninflammatory, scar mechano-bullous form and a generalized, inflammatory, nonscarring variant. The disease mostly occurs in middle adulthood and is very rare in children.

There is a strong association with inflammatory bowel disease [9]. Pathogenetically, EBA is characterized by the deposition of IgG autoantibodies against the type VII procollagen of the anchoring fibril. Histologically, the routine specimen shows a subepidermal blister with intact epidermis. In DIF from perilesional skin, banded IgG antibodies are found along the dermo-epidermal junctional zone. In IIF on NaCl-separated human split skin, which is positive in 50% of cases, circulating IgG or, less commonly, IgA autoantibodies bind in the bladder floor.

Western blot and ELISA can be used complementarily to detect circulating IgG autoantibodies [10]. Therapy of MSDs is difficult, often unsatisfactory, and mainly aimed at immunosuppressive effect. Therefore, the current treatment options are primarily systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, or colchicine. In addition, there are reports of a positive response to the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab in treatment-resistant cases.

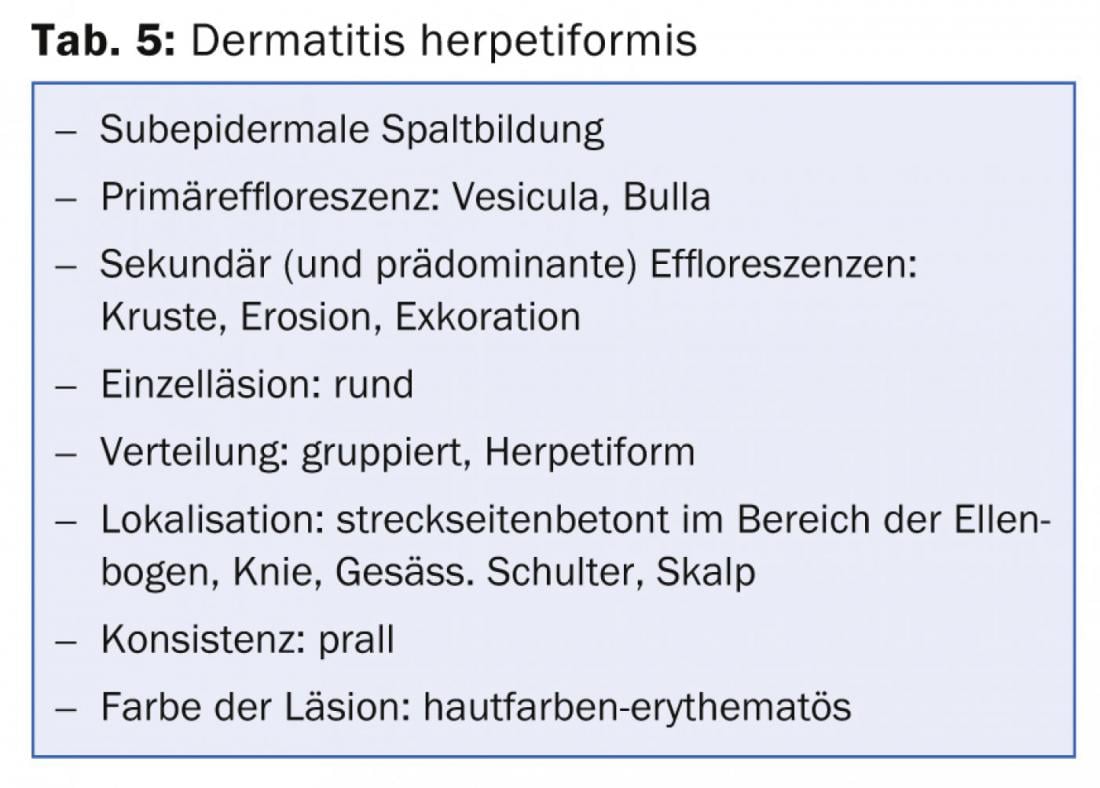

Dermatitis herpetiformis

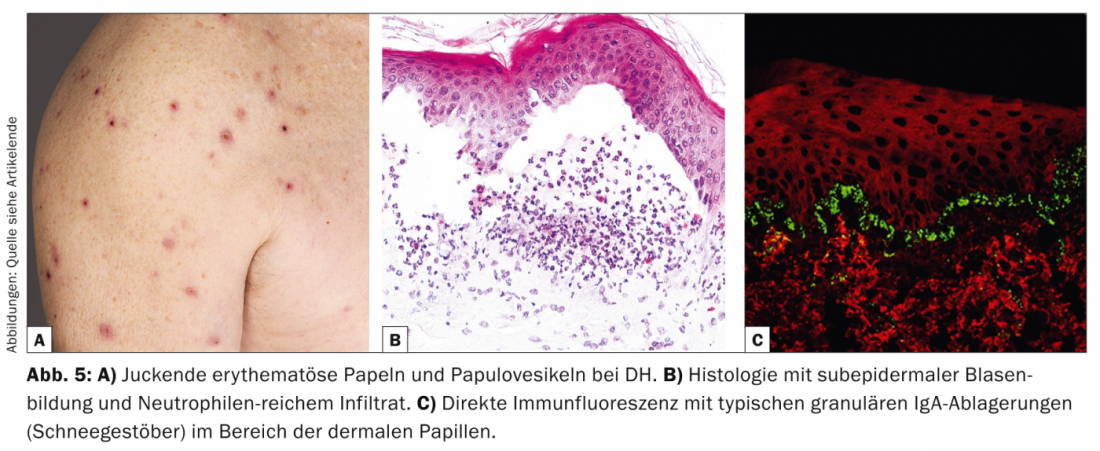

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH, Tab. 5, Fig. 5) is a rare cutaneous manifestation of gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac disease) and presents with violently pruritic erythematous papules and papulovesicles, which are mainly extensor and sacral.

Pathogenetically, both DH and celiac disease are associated with the HLA-DQ2 genotype, in which IgA autoantibodies to reticulin, endomysium, and tissue transglutaminase resp. epidermal transglutaminase are directed. Histologically, there is subepidermal cleavage and neutrophil-rich infiltrates with partial microabscess formation [11].

Histologically, DH appears similar to linear IgA, bullous dermatosis, but granular IgA deposits (snowflakes) are found in the DIF of perilesional skin in the area of dermal papillae. Therapeutically, the gluten-free diet is the main focus, improving both gastroenterological symptoms and cutaneous symptoms [12]. Alternative options include dapsone, sulfapyridines, or systemic corticosteroids. Dapsone results in improvement of skin lesions but not intestinal symptoms.

Dr. Emmanuella Guenova, M.D.

Image sources:

Clinical images: Photo archive of the University Hospital Zurich

Histological images: Emmanuella Guenova, M.D.

Immunofluorescence Illustrations: Birgit Fehrenbacher

Literature:

- Bolognia, JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV: Dermatology. 2012: Elsevier Health Sciences UK.

- Chan LS: Blistering Skin Diseases. 2009: Taylor & Francis.

- Guenova E, et al: Tinea incognito hidden under apparently treatment-resistant pemphigus foliaceus. Acta Derm Venereol 2008; 88(3): 276-277.

- Lebeau S, et al: Pemphigus herpetiformis: analysis of the autoantibody profile during the disease course with changes in the clinical phenotype. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35(4): 366-372.

- Heizmann M, et al: Successful treatment of paraneoplastic pemphigus in follicular NHL with rituximab: report of a case and review of treatment for paraneoplastic pemphigus in NHL and CLL. Am J Hematol 2001; 66(2): 142-144.

- Marazza G, et al: Incidence of bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus in Switzerland: a 2-year prospective study. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161(4): 861-868.

- de las Heras MN: Linear IgA bullous dermatosis of childhood: good response to antibiotic treatment. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39(3): 395-397.

- Tashima S, et al: A case of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis with circulating IgA antibodies to the NC16a domain of BP180. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53(3): 207-209.

- Hundorfean G, Neurath MF, Sitaru C: Autoimmunity against type VII collagen in inflammatory bowel disease. J Cell Mol Med 2010; 14(10): 2393-2403.

- Calabresi V, et al: Sensitivity of different assays for the serological diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: analysis of a cohort of 24 Italian patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28(4): 483-490.

- Hall MA, Lanchbury JS, Ciclitira PJ: HLA class II region genes and susceptibility to dermatitis herpetiformis: DPB1 and TAP2 associations are secondary to those of the DQ subregion. Eur J Immunogenet 1996; 23(4): 285-296.

- Hervonen K, et al: Dermatitis herpetiformis in children: a long-term follow-up study. Br J Dermatol 2014 [Epub ahead of print].

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- In all bullous autoimmune dermatoses, in addition to the medical history, the examination of the entire integument incl. the skin must be performed. the inspection of mucous membranes and nails obligatory.

- If bullous autoimmune disease is clinically or histologically suspected, the diagnosis must be confirmed by detection of the underlying autoantibodies (staining of tissue-bound antibodies in direct immunofluorescence on tissue section or detection in serum by indirect immunofluorescence or ELISA).

- In the therapy of bullous autoimmune dermatoses, the classic immunosuppressive drugs continue to be used (e.g., corticosteroids, azathioprine).

- Newer therapeutic options include anti-CD20 antibodies (rituximab), which lead to a reduction in autoantibodies.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(4): 6-10