The number of psychiatric disorders in internal diseases is up to 35% [1]. Internal diseases can interact with psychiatric diseases. Furthermore, the two can be mutually dependent. Both dementia and delirium have partly internal causes. Conversely, systemic immune diseases as well as disorders of glucose metabolism, thyroid function or parathyroid diseases are in certain cases accompanied by psychopathological phenomena. For the frequent occurrence of somatic illnesses in patients with severe mental illnesses such as depression, the unfavorable lifestyle plays a decisive role. With regard to increased morbidity and mortality in patients with psychiatric disorders, biological changes (e.g., stress hormone activation) are also discussed as possible causes.

The psychiatric disorders most commonly leading to internal medicine problems are dependence/addiction disorders of psychotropic substances [2]. Other examples include stuporous states and self-harming behavior. Thus, Wernicke-Korsakow syndrome caused by thiamine deficiency occurs not only in alcohol dependence but also in malnutrition caused by gastric carcinoma or protracted vomiting. Posthypoxic states and recurrent severe hypoglycemia may be causative for amnestic syndromes. Artificial disorder is particularly problematic, with the diagnostic ambiguities typical of it, resulting from the behaviors of the affected patients [3].

It is now considered established that the risk of developing ischemic heart disease is increased by the presence of depression and that mental illness can adversely affect the course of internal diseases [4]. On the other hand, there is evidence that anxiety disorders may even have protective effects on internal diseases. Patients suffering from an anxiety disorder have a significantly higher life expectancy than people without an anxiety disorder, probably due to lower risk behavior, a more conscious lifestyle, and greater awareness of physical changes.

Dementia

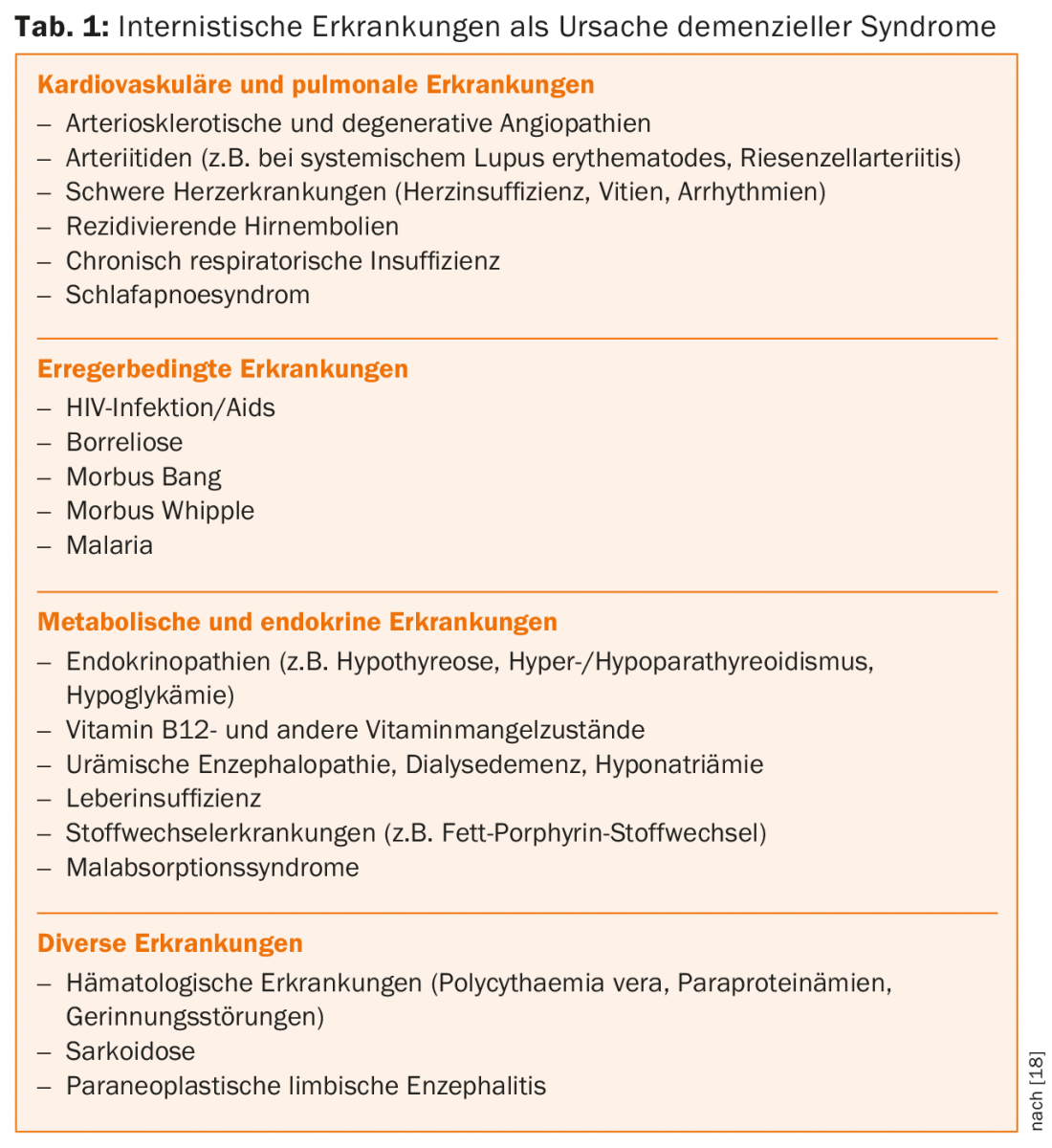

It can be assumed that about 2% of dementia cases have an underlying internal cause (Tab. 1), the targeted treatment of which leads to an improvement in cognitive performance. With a share of 55-70%, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia. Vascular processes and mixed forms are considered the second most common cause of dementia. They are based on arteriosclerotic-degenerative processes of the intra- or extracranial cerebral vessels. In addition, cardioembolic events, inflammatory angiopathies, and coagulopathies should be mentioned [5].

Recent study results point to an increased risk of dementia with co-occurrence of diabetes and depression versus either condition alone [6].

Delir

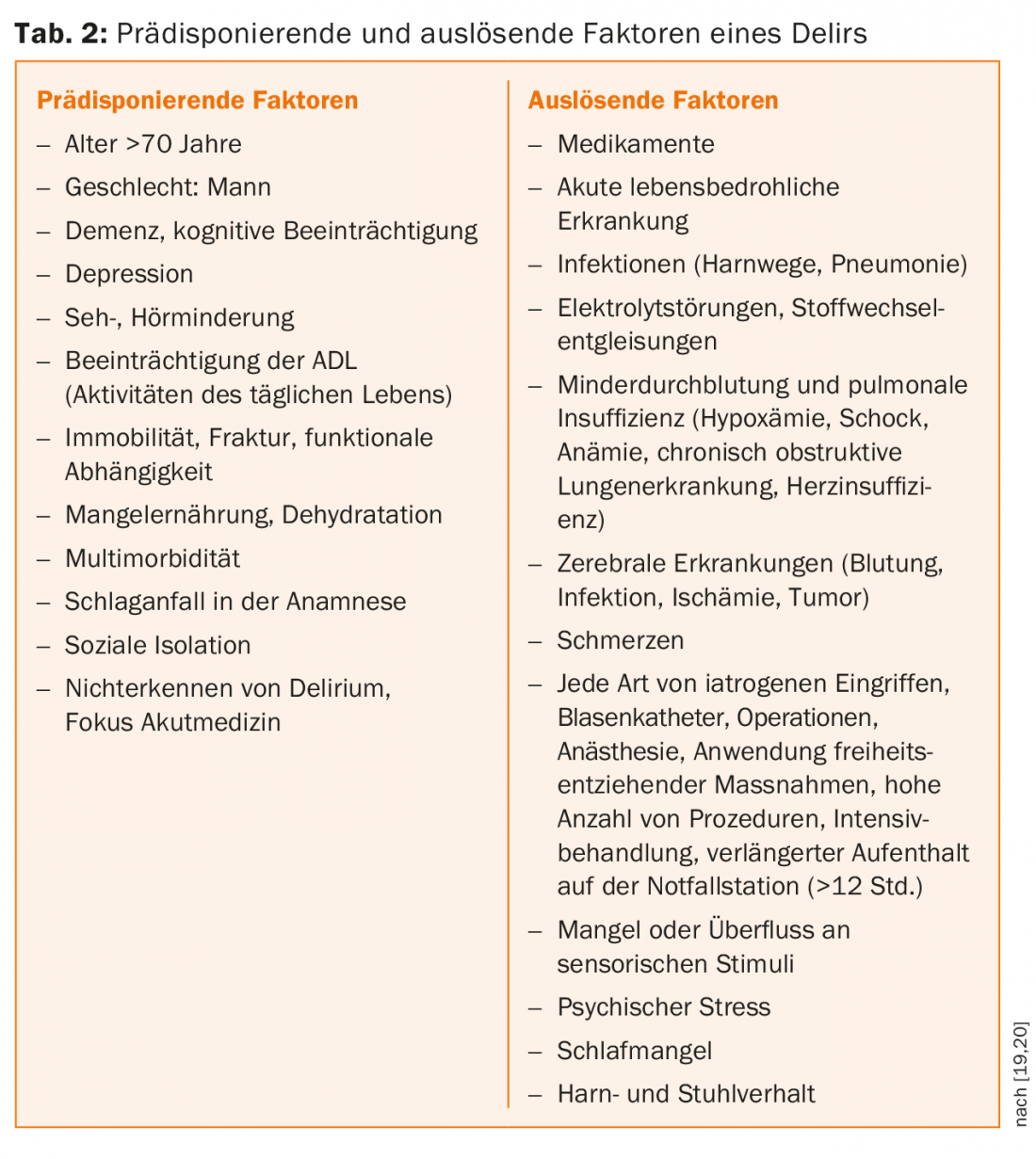

An almost confusing variety of internal diseases can cause delirium. Table 2 provides an overview of possible predisposing and triggering factors. Delirium can be seen as a threshold phenomenon, which is more likely to occur in the presence of an underlying internal disease, the more relevant the pre-existing cerebral damage. In the presence of previous cerebral damage, comparatively mild internal problems – such as a urinary tract infection – may lead to the manifestation of delirium.

The most important internal causes of delirious syndromes are considered to be:

- Infections (e.g. pneumonia, urinary tract infection)

- Disturbances of the water and electrolyte balance (e.g. exsiccosis)

- Endocrinological disorders (e.g. thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction, vitamin deficiencies, renal and hepatic dysfunction, hypoglycemia).

- Cardiopulmonary diseases (e.g. pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, heart failure)

- Pronounced anemia

- Pharmaceuticals used internally (e.g. anticholinergic substances, antibiotics, corticosteroids, cytostatics).

Systemic immune diseases

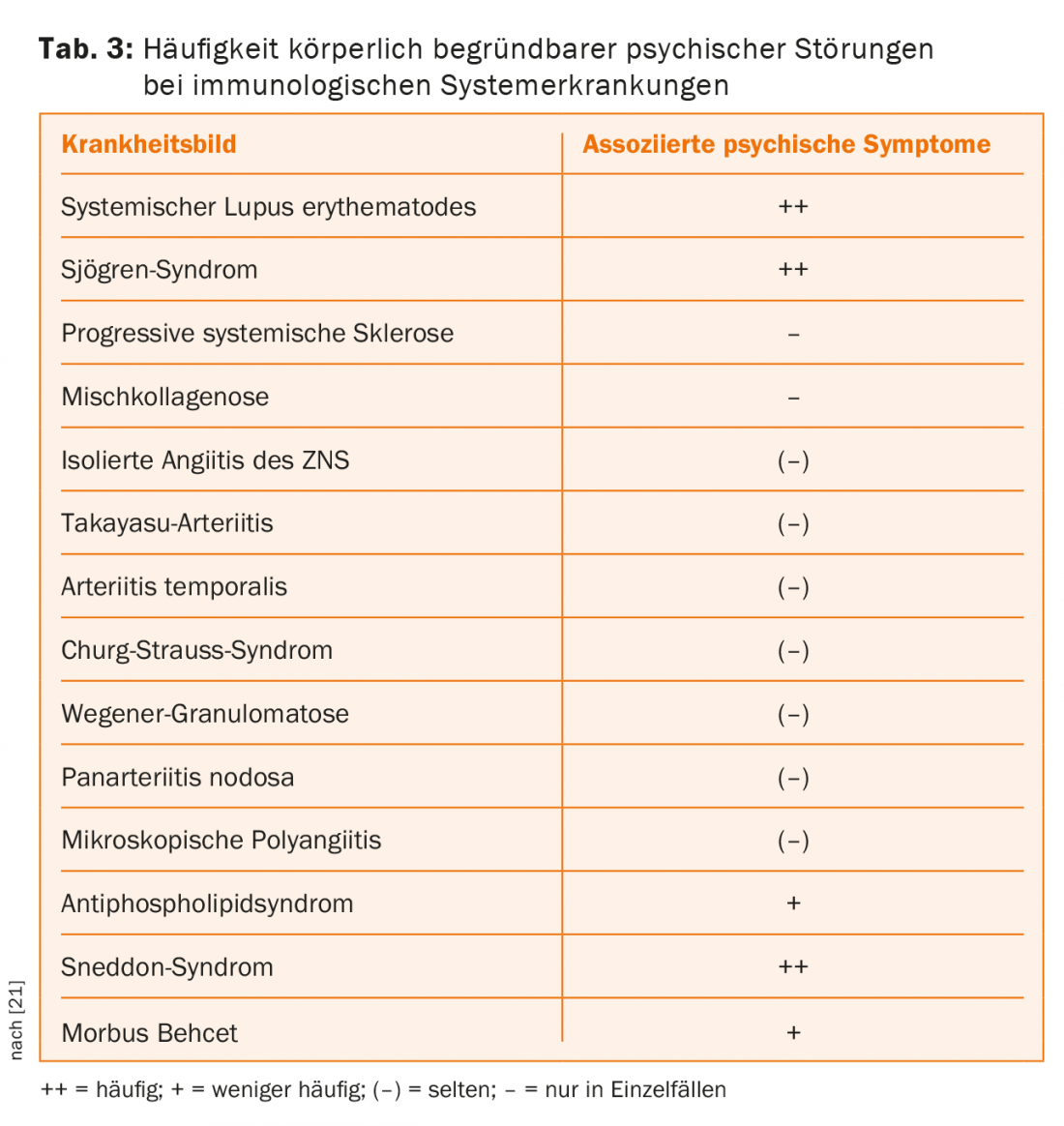

A range of psychopathological syndromes can be observed, particularly in immunological systemic diseases. Paranoid-hallucinatory syndromes, affective disorders (especially depressive syndromes), cognitive deficit syndromes (up to the severity of dementia), other disorders such as organic personality and behavioral disorders, and organic anxiety disorders are evident.

The same psychopathological syndromes may be associated in a nonspecific manner with other disease groups, such as the endocrinopathies, so that no reliable conclusion can be drawn about the etiopathogenetic process from the presence of a particular condition (Table 3) [7].

Glucose metabolism disorders

Acute hypoglycemia can have a multifaceted psychopathological presentation, with clouding of consciousness, psychomotor agitation, and anxiety as the leading psychological symptoms. Chronic recurrent severe hypoglycemia and severe fluctuations in blood glucose can lead to dementia.

Equally as an unfavorable lifestyle, biological changes are discussed as possible causes for increased morbidity and mortality [8]. Quality of life is significantly decreased in comorbid patients with depression and diabetes compared with non-depressed patients with diabetes [9]. Depression is associated with stress and activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HHN) axis with hypercortisolism, which can promote visceral adipose tissue accumulation and increase insulin resistance to clinically manifest type 2 diabetes [10–12]. Comorbidly ill patients should be treated with antidepressants, paying attention to the side effect profile of antidepressants (blood glucose interference, weight gain, cardiotoxic side effects).

Thyroid dysfunction

The psychopathological phenomena that occur in thyroid dysfunction are multifaceted. It is not uncommon for patients with thyroid disease to be first diagnosed in a psychiatric setting (approximately 1-2% in acute psychiatric collectives). Typical psychopathological consequences of hypothyroidism are affect lability, depressive mood states, psychomotor agitation, insomnia and anxiety. Affective symptoms are also frequently prominent in manifest hypothyroidism. Most often, these are inhibited-depressive symptoms, fatigue and lack of drive. Agitated-depressed states are also observed [7].

Parathyroid Diseases

The psychiatric phenomena in hyperparathyroidism and hypoparathyroidism show basically no differences. Depressive symptoms dominate, but cognitive symptoms in the form of forgetfulness up to dementia-like symptoms or delirious states are also observed. Pathogenetically, the parathyroid hormone itself seems to be less responsible than the serum calcium concentration dependent on it.

Depression and cardiovascular disease

Depression is a clear predictor of microvascular and macrovascular disease [13], including cerebral infarcts [14]. Even mild depression in a patient with diabetes multiplies the risk of cardiovascular disease. Since the presence of depression alone also increases the risk of subsequent stroke by approximately 1.5-fold, there is likely a bidirectional relationship between the two conditions of depression and diabetes [4]. Together with the arterial hypertension and dyslipoproteinemia that occur as part of the metabolic syndrome, a significant increase in cardiovascular and mortality risk can be assumed.

Among other things, changes in serotonin balance play a role in the pathophysiology of depression. Several studies of untreated depressed patients have demonstrated alterations in platelet function, resulting in increased platelet aggregation [15]. Furthermore, depression was shown to be associated with a higher density of serotonin 5HT2A receptors on platelets. The influence of the increased density is unclear. That serious cardiac events occur less frequently with the administration of sertraline than in patients taking placebo has not yet been clearly demonstrated. A reduction in platelet endothelial activation factors is suspected, which may confer a morbidity and mortality benefit to sertraline [16]. Several controlled studies suggest that long-term use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in both clinical and preclinical settings leads to successive down-regulation of HHN axis activity and hormone release of cortisol and CRH, respectively, after one to two weeks [17].

Literature:

- Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J: Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study. Journal of the American Medical Association1999; 282: 1737-1744.

- Seitz HK, et al: Alcohol and cancer. In: Seitz HK, Lieber CS, Sivanowski UA (eds.): Handbuch Alkohol – Alkoholismus – Alkoholbedingte Organschäden. J.A. Barth, Leipzig/Heidelberg 1995; 349-380.

- Kapfhammer HP, et al: Artificial disorder – Between deception and self-harm. Nervenarzt 1998; 69: 401-409.

- Baghai TC, et al: Major depressive disorder is associated with cardiovascular risk factors and low omega-3 index. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72: 1242-1247.

- Geldmacher DS, Withehouse PJ: Evaluation of dementia. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 330-336.

- Katon W, et al: Association of depression with increased risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes. The diabetes and aging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69: 410-417.

- Hewer W: Mental disorders and internal diseases. In: Helmchen H, et al. (Ed.): Contemporary psychiatry. 4th ed. Vol. 4. mental disorders in internal diseases. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg/New York 1999; 289-317.

- Knol MJ, et al: Depression as a risk factor for the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2006; 49: 837-845.

- Kruse J, et al: [Diabetes and depression – a life-endangering interaction]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2006; 52: 289-309.

- Holsboer F, Ising M: Stress Hormone Regulation: Biological Role and Translation into Therapy. Annu Rev Psychol 2010; 61: 81-109.

- Weber B, et al: Major depression and impaired glucose tolerance. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2000; 108: 187-190.

- Uhl I, et al: Central serotonergic activity correlates with salivary cortisol after waking in depressed patients. Psychopharmacology 2011; 217: 605-607.

- Piber D, et al: Depression and neurological disorders. Neurologist 2012 Nov; 83(11): 1423-1433.

- Bruce JM, et al: Neuropsychological correlates of self-reported depression and self-reported cognition among patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol March 2008; 21: 34-40.

- Nair GV, et al: Depression, coronary events, platelet inhibition and serotonin reuptake inhibition. Am J Cardiol 1999; 84: 321-323.

- Sebruany VL, et al: Platelet/endothelial biomarkers in depressed patients treated with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline after acute coronary events: The sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) Platelet Substudy. Circulation 2003; 108: 939-944.

- Schüle C: Neuroendocrinological mechanisms of actions of antidepressant drugs. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 2007; 19(3): 213-226.

- Lang C: Dementias: Diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Chapman & Hall, London/Weinheim 1994.

- Pretto M, Hasemann W: Delirium – Causes, symptoms, risk factors, recognition and treatment. Nursing Journal 2006; 3: 9-16.

- Lindesay J, MacDonald A, Rockwood K: Acute confusion – delirium in the elderly, practice manual for nurses and physicians. 1st edition. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern 2009.

- Lieb K, et al: Immunological systemic diseases as differential diagnosis in psychiatry. Nervenarzt 1997; 68: 696-707.

Further reading:

- Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA: Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2-diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 2822-2828.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(6): 28-30.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(10): 14-18