The paradigm shift in diagnostic classification launched some time ago led to modifications in the treatment strategy. Nowadays, phenotype-specific symptom-oriented treatment is considered “best practice”. An interim review and outlook for future therapeutic options.

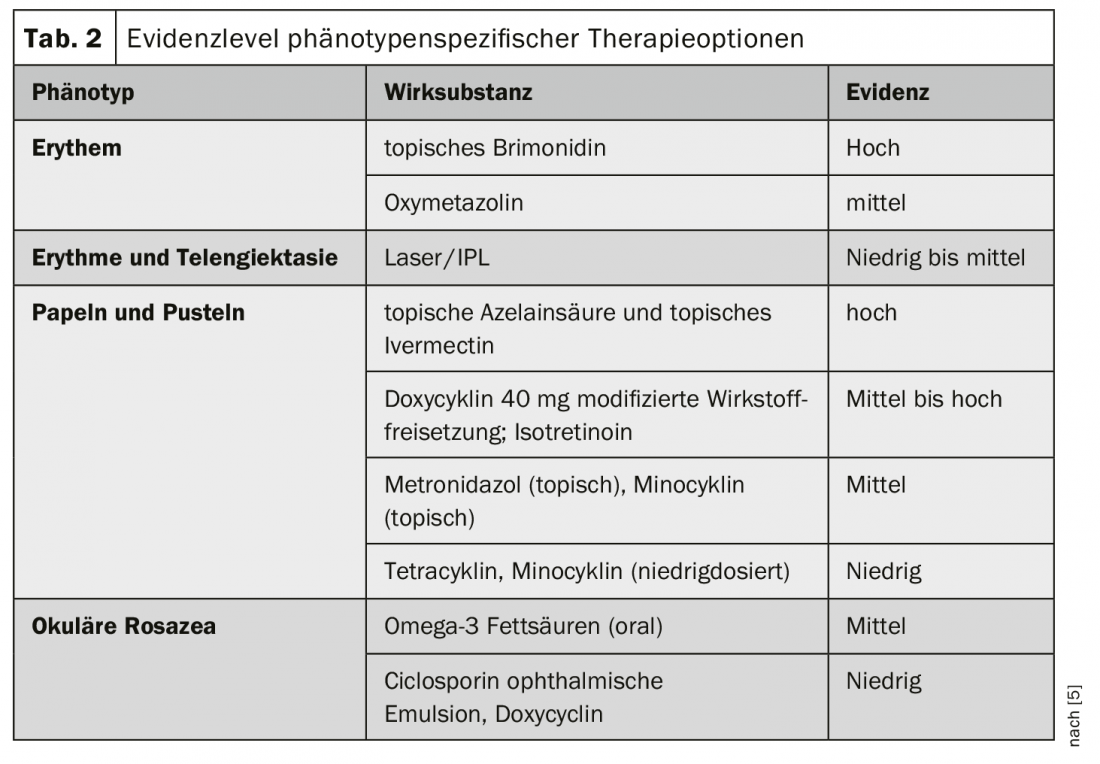

The update of the diagnostic classification by the Global Rosacea Consensus Panel (ROSCO) took place in 2017 (Tab. 1). Hans Bredsted Lomholt, MD, Aalborg, Denmark, presented empirical findings and clinical experience regarding therapeutic implications of the phenotype-based classification at the EADV Annual Congress [1].

Paradigm shift in diagnostic classification

The classification into four subtypes (erythema, papulo-pustular, phyma, ocular) [2] has been replaced by a phenotypic categorization, which should serve as a basis for a symptom-oriented treatment approach. The current diagnostic consensus of phenotype-based diagnostic criteria according to ROSCO is as follows [1,3,4]:

As a primary clinical feature, persistent centrofacial erythema is sufficient for diagnosis, with differential diagnosis to exclude lupus, seborrheic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis. If at least two of the major features are present (papules and pustules, telangiectasia, ocular manifestations), a diagnosis of rosacea may also be made. In the presence of papules, acne/comedones should be excluded as a differential diagnosis. Regarding ocular symptoms, Dr. Bredsted Lomholt points out that referral to an ophthalmologist may be advisable. The secondary features (burning and stinging sensations, swelling, ocular manifestations) are not diagnostic, but are very common in rosacea patients in relation to the particularly sensitive skin and impaired cutaneous barrier function. Comorbid seborrheic dermatitis was also frequently observed and there were recent empirical findings demonstrating a higher comorbidity rate of contact dermatitis.

Efficacy evidence for a phenotype-based treatment strategy.

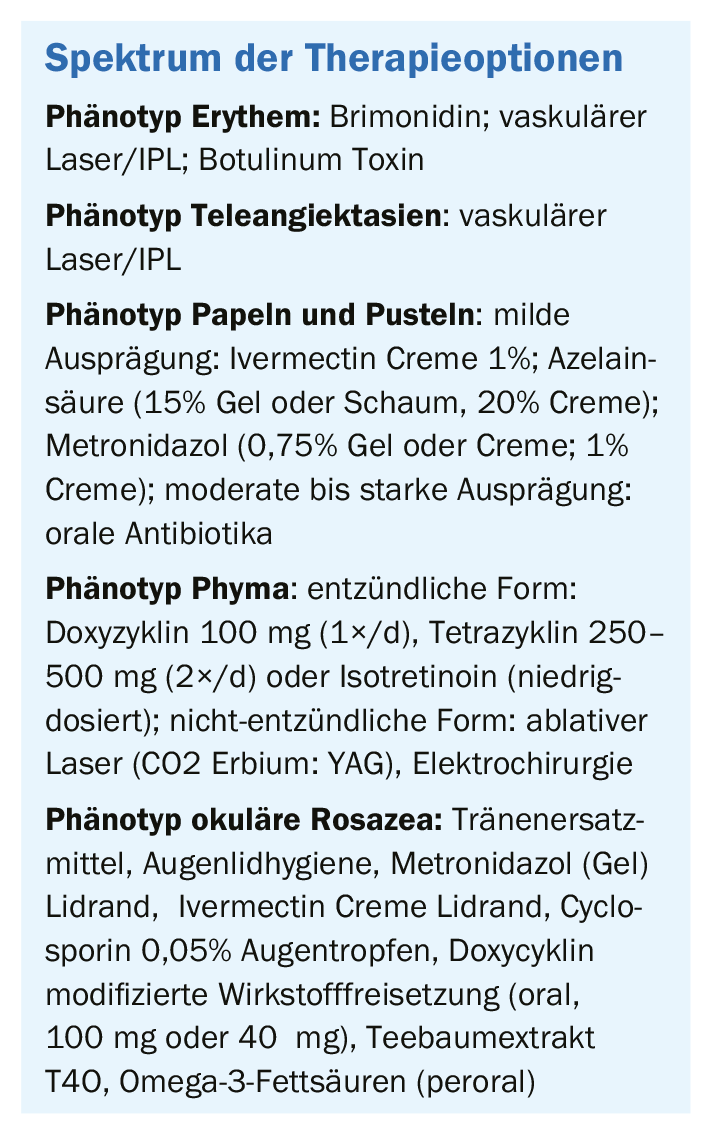

All patients should be educated that in addition to avoiding trigger factors, basic skin care is a very important component, including adequate sun protection (SPF 30+), regular use of well-tolerated moisturizers, and commercially available cleansing products. Furthermore, based on the diagnostic classification, a therapy tailored to the patient’s respective symptoms is indicated. In 2019, a Systematic Review was published in the British Journal of Dermatology with an empirical validation of treatment options based on phenotypic classification [5] (Table 2). The following is a compact overview of diagnosis-specific treatment recommendations [1]:

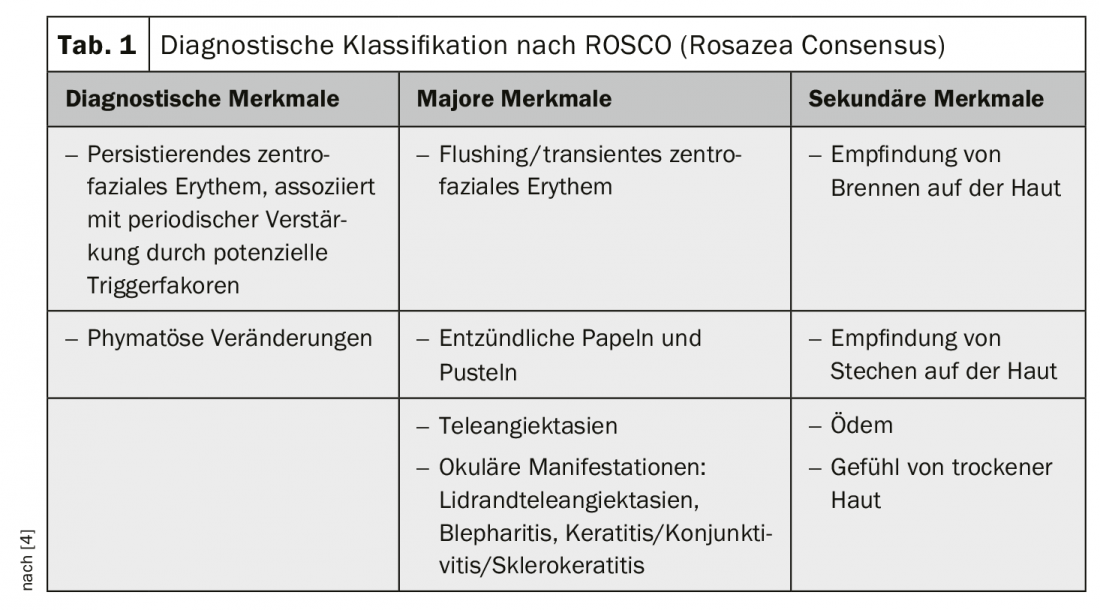

Erythema phenotype: Erythema/flushing is one of the most difficult rosacea symptoms to treat. One of the active ingredients is brimonidine (oxymetazoline hydrochloride cream), which belongs to the substance class of α2-adrenoceptor agonists. Dr. Bredsted Lomholt reported a case report of a patient who experienced short-term relief 30 minutes after application of the drug, which lasted up to 9 hours. However, a relapse of erythema was observed after 12 hours [1]. The speaker pointed out that brimonidine is also not well tolerated by all patients and irritation can sometimes occur. According to his experience, a treatment with vascular laser/IPL leads to better results and an almost lesion-free skin can be achieved. Further, in new studies, botulinum toxin in the right dosage have been shown to be effective for reducing erythema symptoms, according to Dr. Bredsted Lomholt (box) [1,7].

Teleangiectasia phenotype: The use of vascular lasers and IPL has been shown to be effective in treating this phenotype [1].

Phenotype papules and pustules: If symptoms are mild, topical treatment is recommended, e.g., ivermectin cream 1%; azelaic acid (15% gel or foam, 20% cream); metronidazole (0.75% gel or cream; 1% cream). The speaker pointed out that a combination of these substances is also possible to prevent a possible development of resistance of the Demodex mites, e.g. ivermectin cream for 4-6 months and subsequent use of azelaic acid. If moderate or severe symptoms are present, oral antibiotics may be used (doxycycline 40 mg (1×/d), doxycycline 100 mg (1×/d), tetracycline 250-500 mg (2×/d), isotretinoin 10-20 mg (1×/d). The duration of treatment should be as short as possible (about 6-12 weeks), after which therapy can be continued with topical preparations. The correct dosage of antibiotics is crucial to achieve the necessary effect while avoiding the development of resistance, the speaker emphasized. Regarding isotretinoin, the dosage (10-20 mg/d) is lower than for the treatment of acne, the speaker adds.

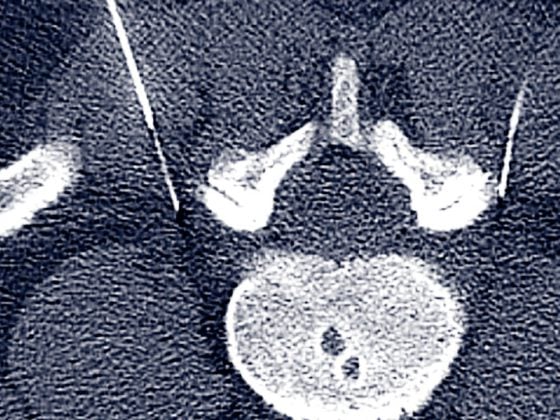

Phyma phenotype: If it is an inflammatory form, doxycycline 100 mg (1×/d), tetracycline 250-500 mg (2×/d), or isotretinoin (low dose) can be used. In non-inflammatory form, treatment by ablative laser (CO2 Erbium: YAG) or electrosurgery is recommended.

Phenotype ocular rosacea: For the treatment of ocular rosacea, there is a relatively wide spectrum of possible measures: Tear substitutes, eyelid hygiene, metronidazole gel eyelid margin, metronidazole eyelid margin, ivermectin cream eyelid margin, cyclosporine 0.05% eye drops, doxycycline modified release (oral, 100 mg or 40 mg), tea tree oil and extract T4O, omega-3 fatty acids (peroral).

Screening for comorbidities recommended

According to a secondary analysis published in 2018, rosacea is associated with numerous comorbidities [8]: mental disorders (depression, phobias), cardiovascular disorders (hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, dyslipidemia), neurological problems (migraine, dementia, Parkinson’s disease), gastrointestinal symptoms (Heliobacter pylori infection, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease), and some others (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis). To date, the underlying pathomechanism of these correlations has not been fully elucidated; there are various hypotheses (e.g., link to specific genes, external trigger factors, inflammatory processes, microorganisms, etc.). With regard to the microbiome, there have been studies showing that antibiotic treatment of bacterial foci in the gut led to relief of rosacea symptoms [9]. To find out more about the possible pathomechanisms involved in comorbidities, further studies are needed, the speaker mentioned in conclusion, pointing out that screening for possible comorbidities should be performed as part of the diagnostic workup.

Literature:

- Lomholt, HB: Diagnosis and Management of Rosacea. Hans Bredsted Lomholt, MD, slide presentation, Aalborg, EADV Congress, Madrid, Oct. 11, 2019.

- Wilkin J, et al: Standard classification of rosacea: Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46: 584-587.

- Gallo RL, et al: Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: The 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 148-155.

- Tan J et al: Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global Rosacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 431-438.

- Van Zuuren EJ, et al: Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181: 65-79.

- Kim MJ, et al: Assessment of Skin Physiology Change and Safety After Intradermal Injections With Botulinum Toxin: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Split-Face Pilot Study in Rosacea Patients With Facial Erythema. Dermatologic Surgery 2019; 45(9): 1155-1162.

- Choi JE, et al: Botulinum toxin blocks mast cells and prevents rosacea-like inflammation. J Dermatol Sci 2019; 93: 58-64.

- Haber R, Gemayel ME: Comorbidities in rosacea: A systematic review and update: JAAD 2018M 78: 786-792.

- Drago F, et al: The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in rosacea: A 3-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2016; 75 (3); e113-e115.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2019; 29(6): 24-25 (published 7/12/19, ahead of print).