Causes and causal relationships of headaches are complex. Isabelle Rittmeyer, MD, Chief of Psychosomatic Medicine at the Zurich Rehab Center Davos, focused on psychosomatic aspects at the SGAIM Fall Congress 2018. Their goal: to give headache patients tools in their hands.

Common therapeutic approaches for headaches include the administration of analgesics and triptans, prophylactics and oxygen, Botox injections, or external cranial neurostimulation, for example using Cefaly®. Isabelle Rittmeyer, MD, head of psychosomatic medicine at the Zurich Rehab Center Davos, takes a different approach. Without denying the effectiveness of the methods mentioned, she emphasizes that headaches are often caused psychologically and that medicinal approaches therefore fall short.

Psychosomatic interplay

Psychological stress is the driver of a development that can force the sufferer into a vicious circle (Fig. 1). Headaches, like a chronic illness, are a stressful situation, according to Dr. Rittmeyer. Despite their health limitations, many people would turn to painkillers to avoid missing work. Negative emotions such as fear or anger develop from this, possibly even in relation to the headache (fear of pain/rage at pain). These manifest themselves, among other things, in the form of altered, counterproductive behavior. An inner “defensive posture” can lead to body malpositions (e.g. shoulder high). Lack of training, for example due to lack of energy or time vessels, manifests itself in muscular imbalance associated with reduced trunk stability and weak muscles in the shoulder and neck area. Other behaviors involve altered sleep/wake rhythms with irregular performance, different eating behaviors, bruxism, and possibly increased performance demands. Increased medication use, which can develop into MOH (“Medication Overuse Headache,” on ≥15 days per month), is also problematic. The critical limit is 10 (mixed analgesics) or 15 (simple analgesics) days per month – those who take medications more frequently put themselves at risk of MOH [1]. In addition to these internal factors, there are external factors such as poor ergonomics at the workplace or unsuitable or even missing glasses in the case of eye problems. Sleep ergonomics also play a key role: “If you wake up in the morning with a headache, you need to observe how you lie in bed.”

Making the psychic tangible

A neurological treatment regimen includes assessment of headache localization and severity and appropriate medication. In contrast, a psychosomatic assessment focuses on the interplay between activities and psychological and somatic processes. For example, an upcoming phone call with a supervisor may trigger stress and consequently headache.

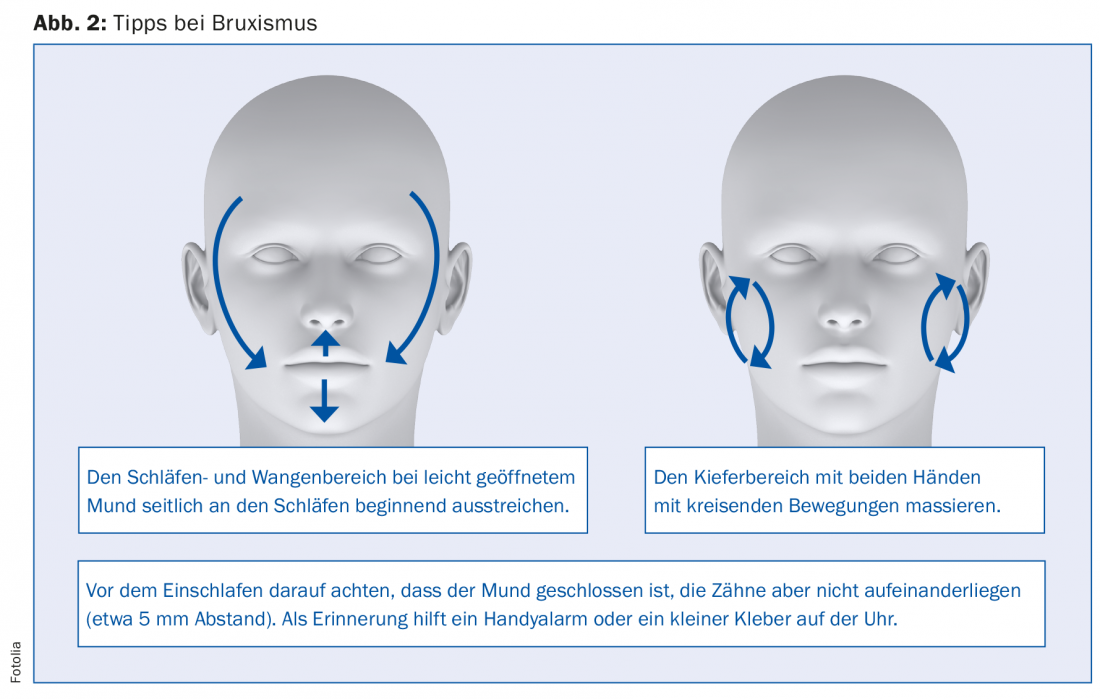

Dr. Rittmeyer explores this connection together with the patient by means of a headache protocol (Tab. 1) . An important part of this protocol is the description of the state of mind. Talking about feelings is difficult for many patients, but at the same time it is the key to understanding psychosomatic interactions. The speaker described this by means of a case example: Patient A had woken up with a severity 4 headache the morning before the therapy session after weeks of being free of symptoms. The thought that everything had been “for nothing” made her angry. While she was still filling out the questionnaire and naming her feelings, the headache increased to 6. In this way, the mechanism became tangible for them. As an aid, one can work with the “hand of feelings”, which visualizes the five basic feelings of joy, fear, anger, love and sadness; for headache patients, the feelings of tension, fear and anger, play a particularly central role. This is often linked to certain personality aspects: a high sense of responsibility, the inner guiding principle “I must not be weak”, high pressure to perform with a lack of self-care, perfectionism and suppression of feelings. Because it is difficult to talk about feelings, questions relating to these personality aspects (“Do you feel responsible for XY?”, “Do you like to do your work perfectly?”, “Do you have high expectations of yourself?” etc.) are suitable in the case history interview.

Where the Psychic and the Somatic Come Together: Trigger Points

Travell and Simmons describe trigger points as localized indurations of an overworked muscle bundle/string of skeletal muscle that responds painfully (locally or radiating) to pressure. They distinguish between active and latent trigger points. While active points produce a permanent muscle-specific pain pattern, latent points respond only on palpation [2]. Palpation of trigger points can also be used to feel headache localization and severity. Several studies suggest that psychological stress activates trigger points. Emotional or mental stress showed increased activity of myofascial trigger points, while adjacent muscles were not affected [3,4]. Furthermore, there seems to be a correlation between trigger point activity and negative feelings such as fear, anger, and hopelessness [5]. In the treatment of trigger points, the importance of manual medicine is repeatedly referred to [6]. Manual medical work with trigger points can also facilitate access to psychosomatic therapy approaches for headache patients.

Activate the patients

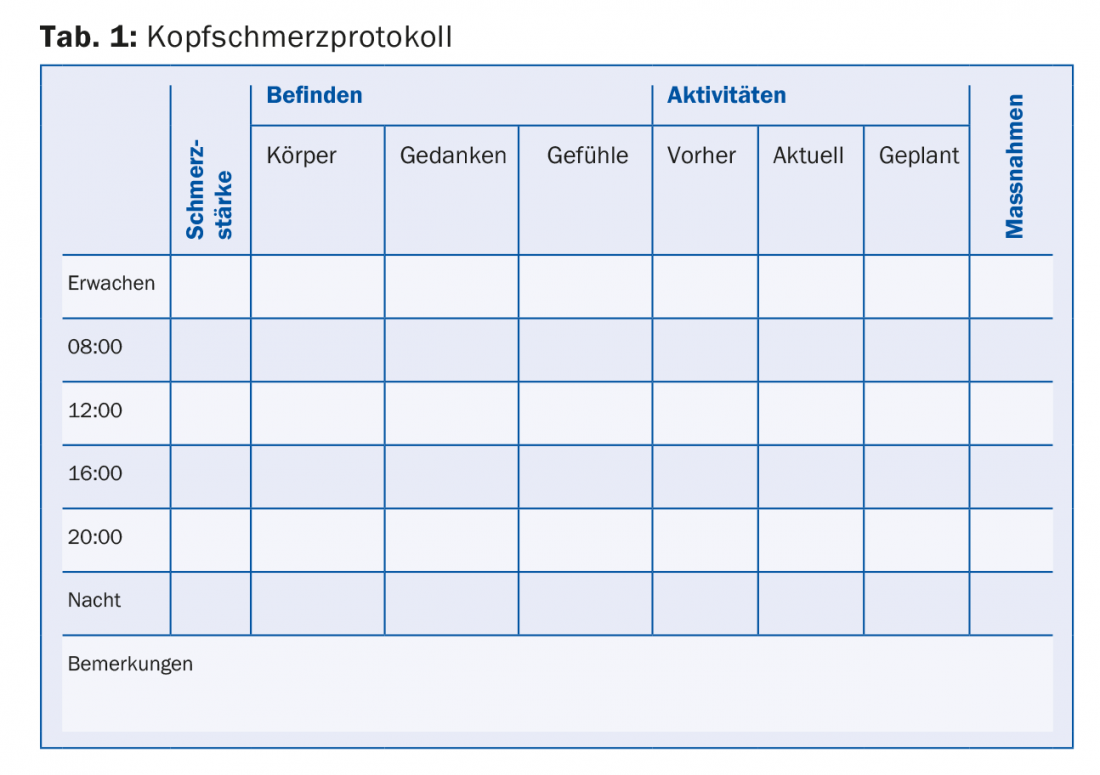

“It’s important to me that my patients can do something themselves, that they have tools,” Dr. Rittmeyer emphasizes. “Self-management” is then also the core message. As a result, the patient goes into action and is no longer powerless in the face of the headache. Trigger points, for example, are easy to treat yourself, for example with the help of a fascia roller (e.g. Blackroll®) or ball. In addition, the cervical spine muscles should be trained to prevent overstraining of individual muscle parts. This is achieved by simple exercises, for example by the patient lying on his back or stomach and slowly raising his head. Other aids include heating pads, massage cushions or ergonomic seat cushions (e.g. SISSEL®). The latter support patients in changing their attitudes in a way that promotes health. A daily facial massage (Fig. 2 ) helps against bruxism, which often occurs in connection with headaches and whose risk factors include stress [7]. Finally, the speaker points out that the increased use of headache medication should be avoided due to the risk of MOH. Antidepressants are an alternative medication, with Anafranil® having proved particularly effective in the speaker’s view.

Source: SGAIM Autumn Congress, September 20-21, 2018, Montreux

Literature:

- Diener HC, et al: Medication overuse headache (MOH), S1 guideline, 2018. In: German Society of Neurology: Guidelines for diagnosis and therapy in neurology.

- Simons DG, Janet GT, Simons LS: Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual Vol. 1 and 2, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

- McNuthy WH, et al: Needle electromyographic evaluation of trigger point response to a psychological stressor. Psychophysiology 1994; 31: 313-316.

- Lewis C, et al: Needle trigger point and surface frontal EMG measurements of psychophysiological responses in tensiontype headache patients. Biofeedback & Self-Regulation 1994; 3: 274-275.

- Linton SJ: A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine 2000; 25: 1148-1156.

- Dommerholt J, Bron C, Franssen J: Myofascial trigger points. Evidence-based review. Manual Therapy 2011; 15: 1-13.

- Ahlberg J, et al: Reported bruxism and stress experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002; 30: 405-408.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(11): 31-33