The 7th Symposium of the Swiss Society for Anxiety & Depression took place as every year in beautiful spring weather in Zurich. Two topics were focused on: the potential for primary prevention of psychiatric illness through physical activity and the treatment of the elderly with anxiety disorders and depression.

How effective and evidence-based are sport and exercise for the prevention of mental illness? On this question, Prof. Dr. phil. Markus Gerber, Department of Sport, Exercise and Health, University of Basel, comments. In Switzerland, the Federal Office of Sport issues recommendations for the extent of physical activity. 2.5 hours of moderate-intensity exercise (e.g., bicycling, walking, gardening) or 1.25 hours of high-intensity exercise (e.g., jogging, cross-country skiing) per week are considered beneficial to health.

The fact that physical activity has a positive influence on health has been proven many times today. An important study was published in 1978: it showed for the first time that people who exercised a lot had a significantly lower risk of heart attack [1]. As a result of this study, exercise began to be integrated into the rehabilitation of patients with heart disease – previously, patients had to lie down for several weeks after a heart attack.

Exercise protects against anxiety and depression

“The effects of physical activity on mental illness were not studied until much later,” the speaker said. A first meta-analysis on exercise and anxiety disorders was published in 1991 [2]. It found that exercise lasting at least 20 minutes reduced state anxiety; regular exercise lasting at least ten weeks also reduced trait anxiety. Compared to other forms of therapy such as music, behavioral or group therapy, physical exercise has a significantly better effect (the exception is pharmacotherapy).

The first meta-analysis examining the impact of exercise on depression was in 2001 [3]. It too showed that exercise was associated with fewer depressive symptoms. However, a crucial question remained unanswered at this point: Does lack of exercise increase the risk of depression or is lack of exercise the consequence of depression? Only a prospective study from Denmark brought clear results [4]:

- People who do little exercise are at increased risk for depression.

- Inactivity has a particularly negative effect on women.

- Whether the intensity of the movement is high or moderate, it does not matter much.

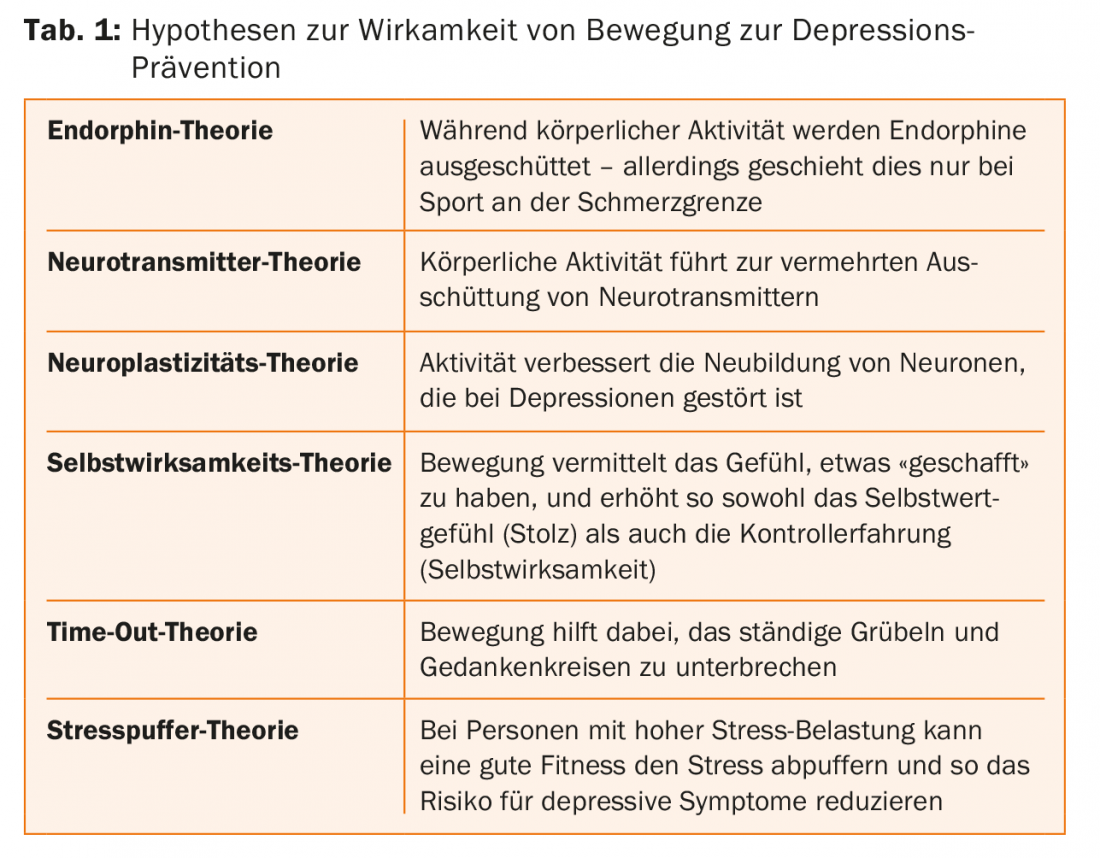

There are several hypotheses as to why exercise can prevent mental illness (Tab. 1). Presumably, all these theories contribute a part to the effectiveness of physical activity.

Physical activity as a form of therapy

There are further arguments in favor of using exercise for the treatment of mental illness: The efficiency of classical therapy methods is limited, exercise also protects against comorbid diseases, and many patients have a positive basic attitude toward exercise and sport. Various studies and meta-analyses indicate that significant efficacy of exercise programs for depression exists only above a certain level of energy expenditure (e.g., jogging twice for 50 minutes or walking six times for 30 minutes per week) [5]. Guided exercise programs seem to have a particularly beneficial effect. “Today, all psychiatric hospitals in Switzerland offer exercise programs,” Prof. Gerber pointed out, “but unfortunately only 25% of patients participate.”

However, the effects of sports therapy are not sustainable – when you stop exercising, the positive effects disappear. Neither initial treatment nor antidepressant use during 12 months of follow-up was associated with remission rate. The only significant predictor of remission rate was physical activity during follow-up. Furthermore, several cognitive variables that control exercise behavior are impaired in depressed individuals – compared to healthy individuals (e.g., self-efficacy, implementation intentions, outcome expectations, intention strength, etc.). It is therefore important to strengthen volitional behavioral control in depressed patients, for example, via self-monitoring (pedometer, apps), action plans, barrier management, relapse prevention, contracting, etc.

Depression and anxiety in old age

Prof. Egemen Savaskan, M.D., Head of the Department of Geriatric Psychiatry, Psychiatric University Hospital, Zurich, provided information on treatment options for anxiety and depression in elderly patients. The prevalence of so-called “old-age depression” is high: major depression occurs in 4.4% of older women and 2.7% of older men, and minor depression in as many as 30%. Of these diseases, however, only 16% are recognized and treated! “A lot of education is still needed here,” the speaker emphasized. Anxiety disorders are even more common – a prevalence rate of 5-6% is assumed here.

Comorbidity rates are also high: 47.5% of patients with major depression also have an anxiety disorder, and 26.1% of patients with an anxiety disorder also suffer from major depression. This “duo infernal” is very detrimental to patients: comorbidity increases the severity and treatment resistance of depression and exacerbates somatic symptoms, suicidality, and impairment of daily living skills. Depressive symptoms are similar in old patients as in young ones, but with some peculiarities:

- Less sadness

- More somatic and hypochondriacal complaints (especially frequent: joint pain, back pain and headaches)

- Memory disorders

- More anxiety symptoms

- More apathy and listlessness (“I only manage to do the housework in the afternoon”).

Comorbidities complicate therapy

In elderly patients, somatic comorbidities such as hypertension, osteoarthritis, coronary artery disease, heart failure, or diabetes are often present. These increase the tendency for depression to become resistant to treatment and lead to polypharmacy, which also complicates the treatment of depression. “That’s why it’s important to keep reviewing medication in patients who are taking a lot of medications, and even attempt discontinuation if necessary,” Prof. Savaskan said.

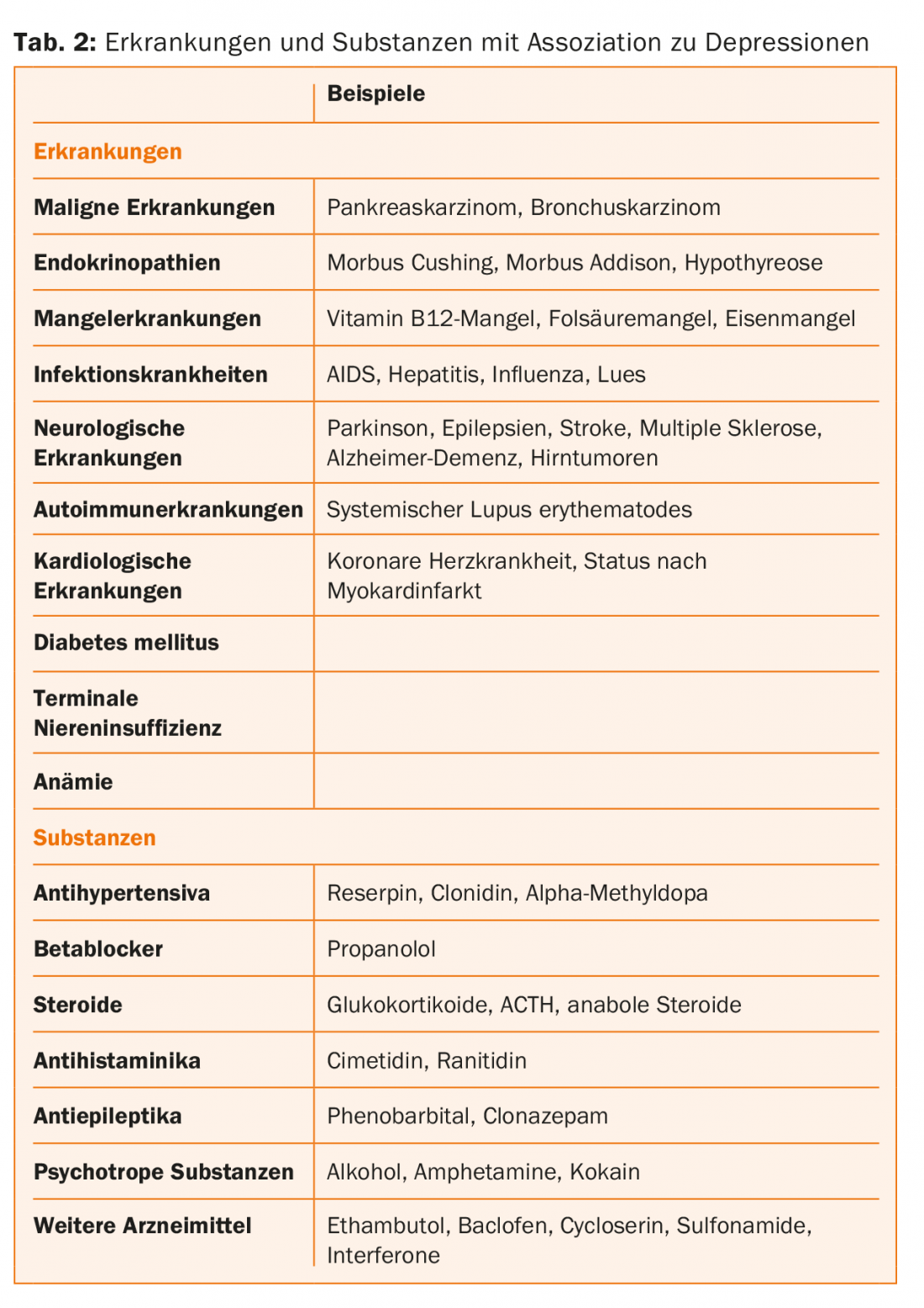

He pointed out various diseases and conditions that increase the risk for depression in old age (Tab. 2) . Particular mention should be made of depression after a cerebral stroke (post-stroke depression): The prevalence is very high (31-52%), there is often resistance to therapy, and comorbidity complicates rehabiliation. Preventive administration of an SSRI after a stroke may reduce the risk that the patient will develop depression, but this is controversial. Depression in PD can also be very persistent; the problem here is that the administration of drive-enhancing antidepressants can worsen motor symptoms.

Depression and dementia

Cognitive dysfunction is also very common in depression. Especially the speed of information processing, executive functions and working memory are affected. There is an additive effect between dementia and depression. Depression that first appears in middle and later adulthood is associated with an increased risk of dementia; “late” depression may also represent a prodromal stage of dementia. And in individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment, additional depression increases the risk of developing dementia. In people who already have dementia, depression is one of the most common comorbidities: At least half of all people with severe Alzheimer’s dementia are also depressed. These patients are at increased risk for more severe symptoms, including psychotic symptoms.

Depression therapy: more than medication

Before starting therapy in an elderly patient, a careful assessment is necessary: Is depression present at all according to ICD-10? Are there psychiatric and/or somatic comorbidities with appropriate medication? What psychosocial stressors are present? Apart from the two main therapeutic measures, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, procedures such as psychoeducation, psychosocial support, activation or exercise therapy are also important.

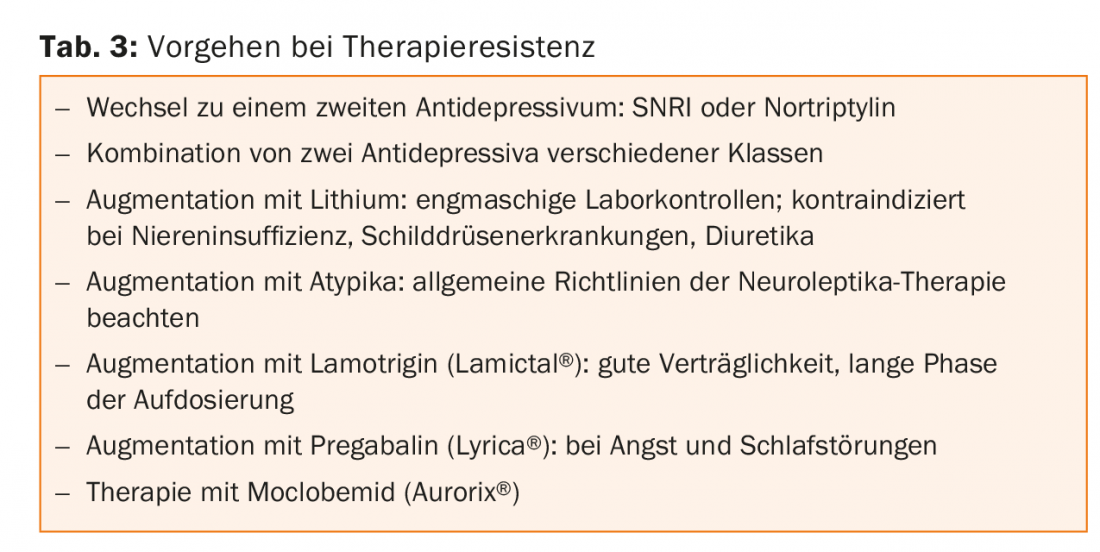

In terms of pharmacotherapy, SSRIs and SNRIs are at the forefront because of their beneficial side effect profile. In particular, SSRIs/SNRIs are less likely to prolong QTc time than tricyclics or atypical antipsychotics. Benzodiazepines should in principle be used only in crisis situations and as adjunctive therapy until the effects of antidepressants begin to take effect – low dosages are recommended for elderly patients. Atypical antipsychotics may be used in special cases, particularly behavioral disorders in the setting of dementia, anxiety disorders, insomnia, psychosis secondary to Parkinson’s disease, and to augment antidepressants. Smaller studies suggest that light therapy may also be effective for geriatric depression. In case of resistance to therapy, various options are available (Table 3).

Source: 7th Symposium of the Swiss Society for Anxiety & Depression: “Depression, Anxiety and Aging”, April 14, 2016, Zurich.

Literature:

- Paffenbarger RS, et al: Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J of Epidemiology 1978; 180: 161-175.

- Petruzello SJ, et al: A meta-analysis on the anxiety-reducing effects of acute and chronic exercise. Outcomes and mechanisms. Sports Medicine 1991; 11: 143-182.

- Dunn AL, et al: Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression. Med Sci Sport Exerc 2001; 33: 587-597.

- Mikkelsen SS, et al: A cohort study of leisure time physical activity and depression. Prev Med 2010; 51(6): 471-475.

- Dunn AL, et al: Exercise treatment for depression: efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med 2005; 28(1): 1-8.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(3): 38-40.