In a workshop at this year’s KHM Congress in Lucerne, speakers KD Dr. med. Stephanie von Orelli, Frauenklinik Stadtspital Triemli, Zurich, and Dr. med. Elisabeth Bandi-Ott, UniversitätsSpital Zurich, addressed the problem of chronic lower abdominal pain. Often, a multidisciplinary approach is needed in the evaluation and treatment of affected women.

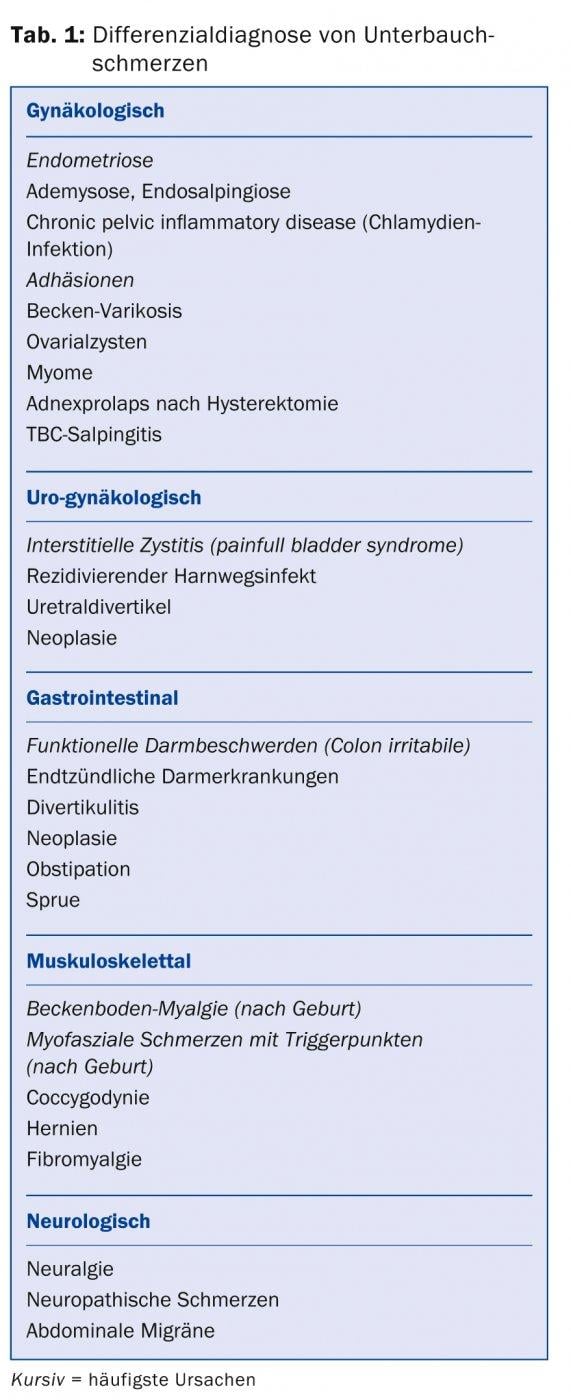

(ee) “The most common gynecologic causes of chronic lower abdominal pain are endometriosis and chronic infections, namely from chlamydia,” said KD Stephanie von Orelli, MD. Although the causes are often gynecological, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal and neurological problems can also trigger the pain (Table 1) . Several studies in the 1980s also showed that women with abdominal pain are frequently affected by psychological and sexual abuse.

“In order for us to do justice to these women, a multidisciplinary approach is needed,” Dr. von Orelli emphasized. She also presented the “Pelvic Pain Assessment” form, a ten-page questionnaire for female patients to precisely ask about pain and other symptoms (https://healthcare.utah.edu/womenshealth/documents/new/pelvic-pain-questionnaire.pdf). This questionnaire is hardly something for everyday use, but in individual cases it can help the woman to describe and narrow down her complaints more precisely.

Endometriosis: common cause of infertility

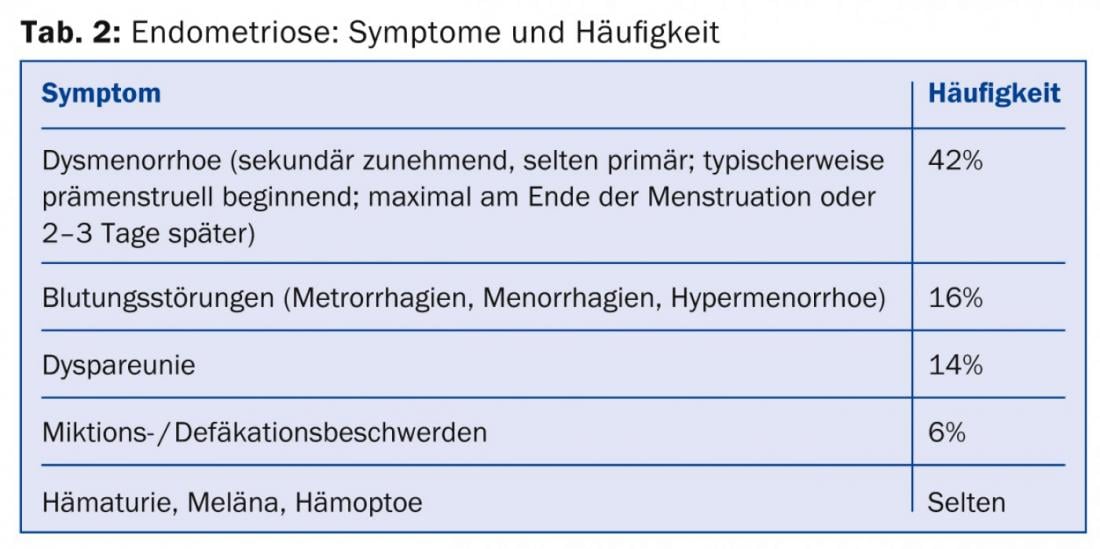

In endometriosis, endometrial glands and stroma are located outside the anatomical boundaries of the endometrium, most commonly in the lesser pelvis. Different forms are distinguished: diffuse infiltrative, focal and pseudocystic forms of endometriosis. The most typical symptom is cyclic pain, which increases with months and years (Tab. 2). Endometriosis is also a frequent cause of infertility: 21-47% of all infertility patients suffer from this disease. An estimated 1-5% of all women have endometriosis, with as many as 8-12% in women of reproductive age. However, approximately 30-50% of affected women do not experience clinical symptoms. If a woman has a first-degree relative with endometriosis, her risk for the same condition is increased by a factor of 7.

The pathogenesis of endometriosis is unclear. Two theories are in the foreground: The carry-over resp. Implantation theory (carryover of endometrial cells by retrograde menstruation, tubal dysfunction, surgery, or lymphogenic/hematogenic) and the coelomic metaplasia theory (re-emergence of endometrial cells as differentiation products of metaplastic coelomic cells).

Four severity levels

Laparascopy and histology are necessary for definitive diagnosis of endometriosis. An MRI of the pelvis usually doesn’t do too much, but is sometimes useful to clarify any ureteral congestion. The aspect of endometriosis lesions is very diverse and depends on the affected organ. In peritoneal endometriosis, early, active foci can be distinguished from advanced foci and burned-out, “healed” lesions. Endometriomas or “chocolate cysts” (blood-filled cysts) often form in the ovary, while more firmly attached nodular changes tend to form in the Douglas space and sacro-uterine ligaments. Adenomyosis is a special form of endometriosis in which the endometrial glands are located in the myometrium – this form can only be treated by hysterectomy. According to the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine score (rASRM score), endometriosis is classified into four severity levels, from stage I (minimal endometriosis) to stage IV (severe endometriosis).

Before therapy is planned, the goal should be discussed: Does the patient want to become pregnant? Or is freedom from pain more important to them? The primary focus is on surgical removal of as many foci as possible; this measure also increases the chances of subsequent pregnancy. Drug therapy options include the administration of hormonal anticonceptives in the long cycle, oral progestogens (Visanne® 2 mg/d without interruption) and relapse prophylaxis with GnRH analogues, especially before a planned pregnancy.

The insertion of a hormonal IUD (Mirena® IUD) can also reduce pain. Ovarian endometriomas that can be diagnosed by vaginal sonography should be surgically removed – drug therapy alone will not eliminate them.

Interstitial cystitis (bladder pain syndrome)

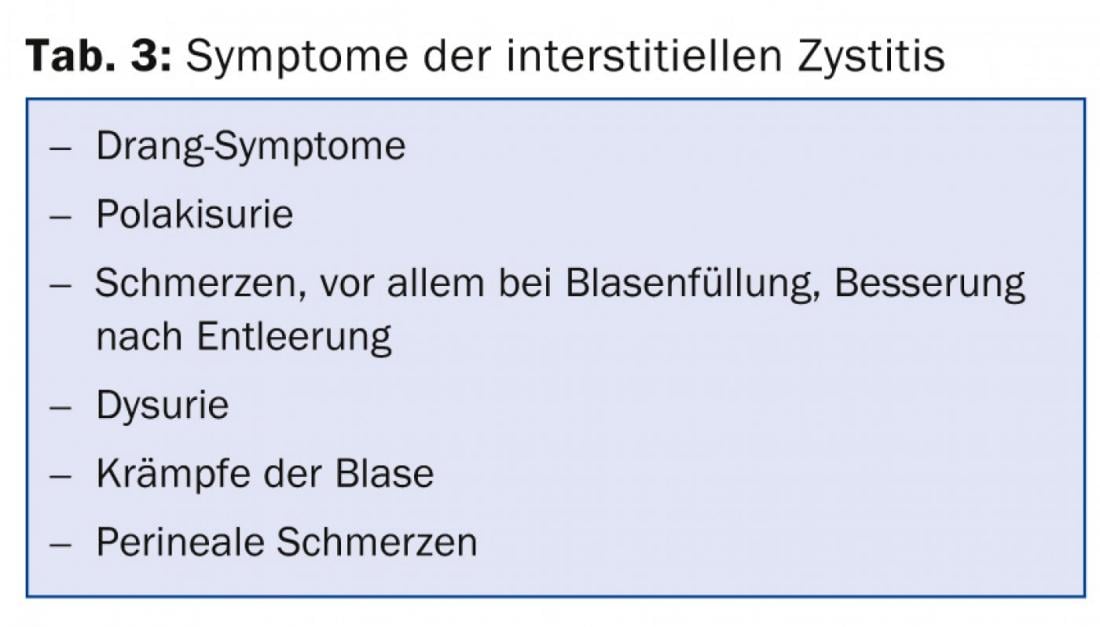

A relatively common but little known condition in our country is interstitial cystitis or “bladder pain syndrome”. It is defined as pain, pressure, and discomfort in the urinary bladder area, along with other urinary tract symptoms (Table 3), for at least six months and after exclusion of infection or other identifiable cause. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, and there are already many support groups of sufferers in the US.

For clarification purposes, a urine status incl. cult, a chlamydia smear, a residual urine determination and possibly a urodynamic clarification. If hematuria is present, cystoscopy with cytology is performed to rule out malignancy. There is no causal therapy. It is necessary to try to achieve a condition that is tolerable for the affected person with various treatment modalities:

- Bladder training with record keeping to gradually increase bladder filling again; at least 45 minutes interval between urination at the beginning, then increase weekly by 15-30 minutes each time.

- Physiotherapy, pelvic floor training, muscle relaxation with biofeedback

- Injection of local anesthetics

- Antidepressants, for example amitryptiline or also SSRIs

- Oral antihistamines (Atarax®), 25-50 mg in the evening

- Painkiller

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Pelvic inflammatory disease most commonly affects young women up to 25 years of age. Chlamydial infection is often asymptomatic, but can also lead to chronic infection with pain (urethritis, endometritis, perihepatitis) and subsequent infertility. Chlamydia trachomatis is an intracellular bacterium, therefore a cell-containing smear must be taken from the cervix, urethra or tube for diagnosis. The pathogen is detected by PCR or LCR; serology is unreliable.

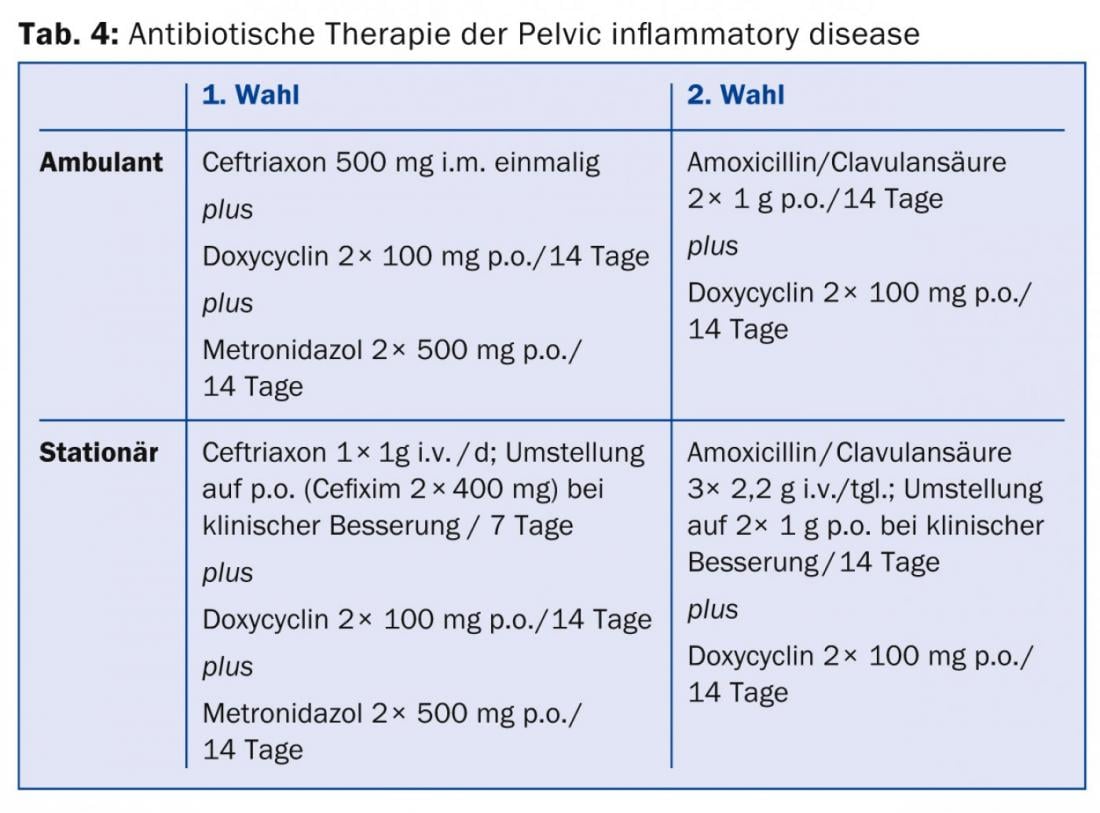

Tetracyclines are given for treatment (Tab. 4), and macrolides are given during pregnancy.

Hospitalization is indicated in cases of poor compliance, intolerance of peroral therapy, pregnancy, poor general health and abscess formation, and to rule out surgical emergencies. “For prevention, I recommend that all women use condoms with a new partner,” reminded Dr. von Orelli, “because the pill alone offers no protection against infection.”

Source: Module Gynecology, 16th Continuing Education Conference of the College of Family Medicine (KHM), June 26, 2014, Lucerne.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(8): 42-44