Colonoscopy is the gold standard of screening for colorectal cancer (CRC), preventing 70-80% of CRC. Screening colonoscopy is covered by health insurance for moderate-risk individuals starting at age 50 and every ten years. Individuals at higher risk require a more rigorous, individualized screening program. Currently, there is no nationally or cantonally organized screening program for CRC, but this should be strived for.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer death in Western countries. In Switzerland, approximately 4000 new CRC cases are diagnosed each year, and nearly half of the patients die [1]. The risk of developing CRC as a European is about 5%. Most cases occur sporadically, but certain factors increase the risk of disease, e.g. a familial predisposition, a hereditary syndrome (Lynch syndrome [HNPCC], Familial Adenomatous Polyposis [FAP]) or inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis; about 15% of all CRC patients belong to the group at increased risk. Age, obesity, diabetes and smoking are also considered proven risk factors, and diet and physical activity also play a role.

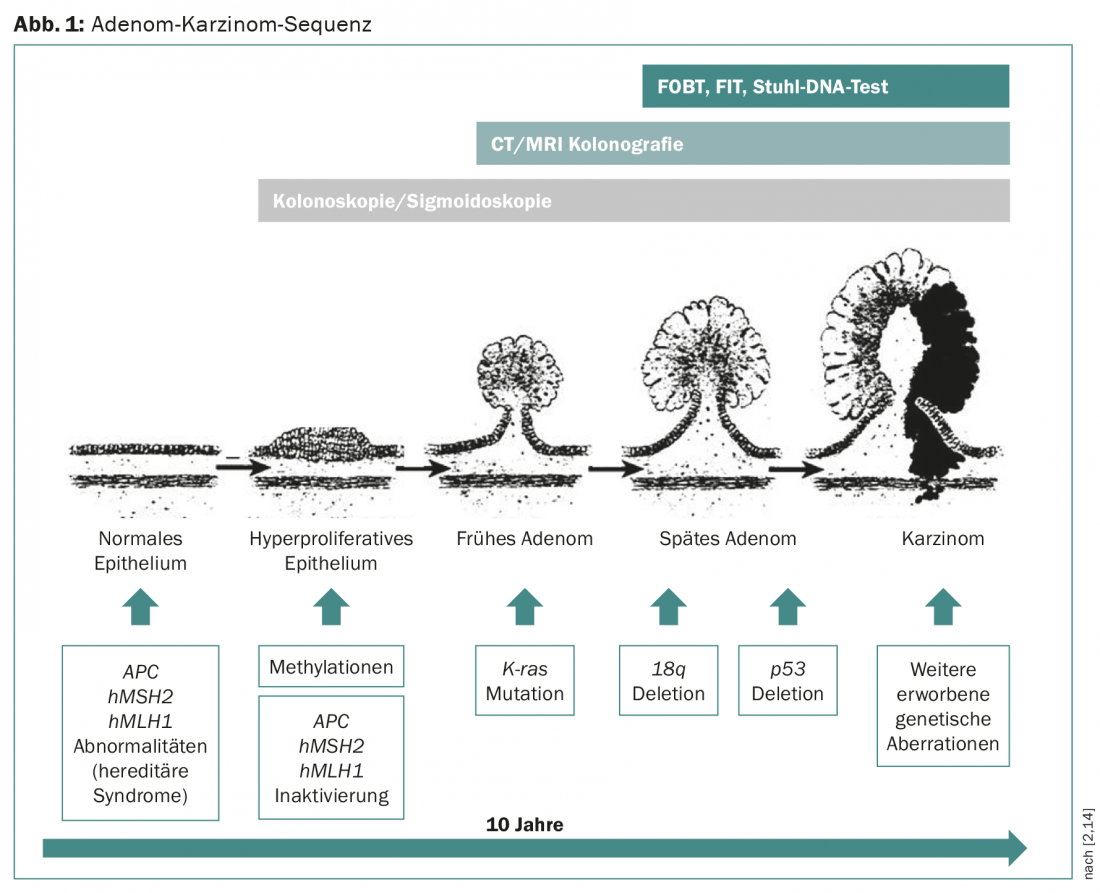

Early stage CRC can be cured at relatively low cost, so early detection and treatment of precursors is important. In metastatic CRC, more costly chemotherapies are often used and the chances of cure are low. Most CRC develop from adenomas that undergo malignant transformation over a latency period of about ten years due to numerous mutations, the so-called adenoma-carcinoma sequence (Fig. 1) [2].

These treatable precancerous lesions, the high prevalence of CRC, and the good prognosis of tumors detected early provide ideal conditions for screening examinations. Two screening methods have been shown in randomized trials to be effective in reducing CRC mortality risk in the intermediate-risk population: fecal occult blood detection test [3] and flexible sigmoidoscopy [5–7]. Meaningful screening tests must be reasonable for healthy individuals, have the highest possible sensitivity and specificity, and be cost-effective. The various screening tests in CRC are discussed below (Table 1).

Detection of occult blood in stool (FOBT/FIT)

The FOBT/FIT is the most commonly used screening test for CRC. It is cheap, non-invasive and easy to perform. A distinction is made between the guaiac test (FOBT), which detects peroxidase activity with hemoglobin, and immunochemical methods (FIT), which detect human hemoglobin in stool using specific antibodies. Several randomized trials using the guaiac test and a Cochrane meta-analysis demonstrated a 16% reduction in relative risk of mortality [3]. A major disadvantage of this method is the low sensitivity for carcinomas (25-38%) and advanced adenomas (16-31%) [4]. This means that the test is false negative in more than 60%. Furthermore, the test is only effective if it is performed regularly (1-2×/year with three samples each). If the test result is positive, endoscopic clarification is required. The more expensive immunochemical methods show better sensitivity compared to the guaiac test, but at the expense of somewhat poorer specificity.

Sigmoidoscopy

Several randomized trials [5–6] and a meta-analysis [7] demonstrated that screening with flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) reduced CRC mortality by 22-31% and incidence by 18-23%. A major problem with this early detection method is that carcinomas and advanced adenomas proximal to the sigmoid are not detected. A recently published meta-analysis demonstrated that in 58% of patients with proximal adenomas, no additional distal lesion was found that would have prompted colonoscopy [8]. Also, the combination of FS and fecal occult blood testing (with the goal of better detecting missed proximal lesions) is not superior to sigmoidoscopy alone. The complication risk of FS is small, and the compliance of the examination is better than that of colonoscopy because the bowel preparation is less rigorous.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy offers the advantage of viewing the entire area of the colorectal mucosa and also allows biopsies and polyp removal in one procedure. When performed by experienced investigators, screening colonoscopy achieves a sensitivity and sensibility approaching 100% [9]. It is thus considered the gold standard of all examinations for early detection of CRC. However, in contrast to guaiac testing and sigmoidoscopy, randomized trials demonstrating a reduction in mortality and incidence of CRC as a primary endpoint have been lacking to date. A 1993 American cohort study showed a 76-90% reduction in CRC incidence by colonoscopy with polypectomy [10]. Currently, three randomized trials of screening by colonoscopy with question of impact on CRC incidence and mortality are ongoing (COLONPREV Study, NordICC Study, CONFIRM Trial). However, the results are not expected for five to seven years. Colonoscopy is recommended as a screening examination by most European and American organizations, starting at age 50 for intermediate-risk patients with an interval of no more than every 10 years. Because the examination is invasive and requires rigorous bowel preparation, compliance in the general population is low.

Virtual colonoscopy (colonography by CT or MRI)

Virtual colonoscopy was developed to circumvent the invasive technique of endoscopy and thereby improve compliance in CRC screening. However, in case of positive findings, endoscopy must be performed to check and treat the pathological findings. In addition, this method also requires bowel preparation and colonic dilatation with fluid or air during the examination. If the patient cannot be expected to undergo an endoscopy, virtual colonoscopy is an alternative.

Stool DNA testing/genetic testing

The stool DNA test is based on the fact that certain DNA changes (methylations, mutations) that occur in tumor cells during carcinogenesis can be detected in the stool. These multitarget DNA tests have fairly good specificity but low sensitivity. There are no studies showing mortality reduction with this procedure. Currently, stool DNA testing is not routinely used.

Recently, the Colox® test developed in Switzerland has become available as a non-invasive screening test in blood for CRC. This involves analyzing a gene signature of 29 genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Through tumor-host interaction, PBMCs store information in the form of nucleic acids generated during the early stages of tumor development as part of the host response. The test shows good specificity for detecting adenomas and carcinomas, but sensitivity is low, especially for precancerous lesions. Again, no studies have yet shown a reduction in mortality risk.

Screening in individuals at intermediate risk

Individuals age 50 and older without a history of polyps or CRC and with a negative family history are considered to be at intermediate risk of CRC. According to guidelines from several international organizations [11] and the Swiss Cancer League [12], screening is recommended from the age of 50 until the age of 75. Colonoscopy every ten years, virtual colonoscopy every five years or sigmoidoscopy every five years are recommended. For individuals who do not qualify for the above methods, the guaiac test is recommended at intervals of one to two years, followed by colonoscopy if the result is positive.

Screening in persons at increased risk

No data from randomized controlled trials are available on the screening of individuals at increased risk. The recommendations are based on opinions of expert groups [11]. Because of the increased risk, screening by colonoscopy should be performed earlier and at more frequent intervals.

Inflammatory bowel disease: Colonoscopy is recommended every one to two years starting about eight to ten years after diagnosis.

Personal history of polyps (increased risk of developing CRC): For low-risk polyps, colonoscopy is recommended five years after initial polypectomy, then every ten years if negative. For high-risk adenomas (>1 cm, 3-10 polyps, high-grade dysplasia), colonoscopy is recommended three years after polypectomy, and every five years thereafter.

High CRC risk due to familial predisposition: the following investigations are recommended for high risk (adenoma/carcinoma in one first-degree relative before age 60 or adenoma/carcinoma in two first-degree relatives):

- Colonoscopy every ten years starting at age 50 if a first-degree relative has been diagnosed with advanced adenoma or carcinoma at age >60.

- Colonoscopy every five years starting at age 40 or the age ten years younger than the age of the diseased relative at diagnosis if a first-degree relative has been diagnosed with advanced adenoma or carcinoma at age <60.

Status after CRC: An initial colonoscopy in the first twelve months after completion of definitive therapy (surgery with/without adjuvant chemotherapy), and every five years thereafter.

Hereditary syndromes (HNPCC, FAP): According to data from observational studies, annual colonoscopies are recommended from 20-25 years of age. Age recommended in Lynch syndrome. For patients with polyposis in the setting of proven FAP, early colectomy should be performed if possible; prior to that, annual colonoscopies are recommended.

Cost absorption

Since July 2013, the costs of CRC screening for people between 50 and 69 years of age with medium risk have been covered by mandatory health insurance in Switzerland (without exemption from the deductible and retention). This includes the cost of a fecal occult blood test every two years or a colonoscopy every ten years.

Conclusions

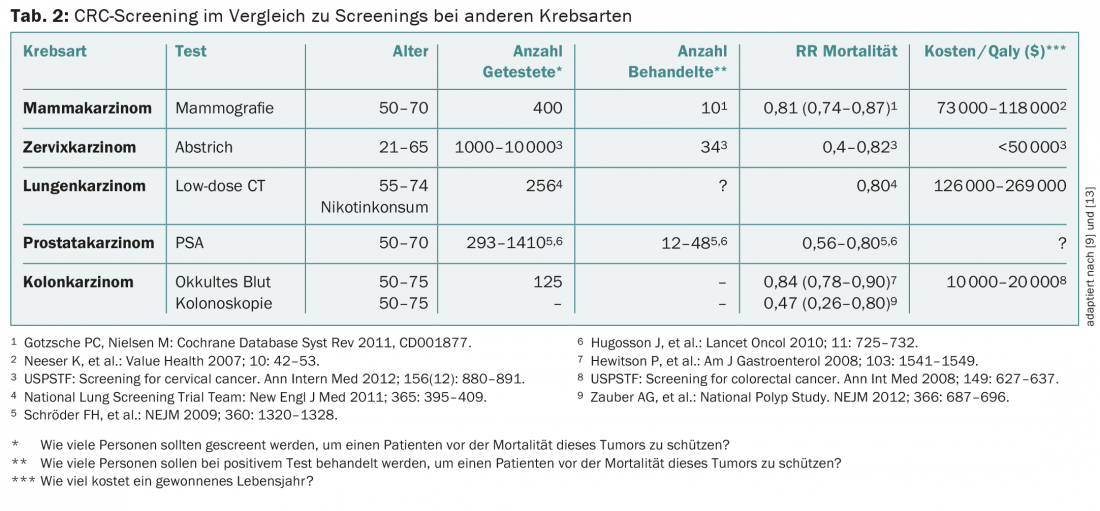

CRC screening is an effective and important method for early detection of one of the most common cancers, which can be well treated by early detection and thus has a good prognosis. As the gold standard, colonoscopy shows the best specificity and sensitivity of all screening methods, but compliance in the population is still too low. However, colonoscopy could prevent 70-80% of colon cancers. Compared to other screening methods, CRC screening is efficient and associated with reasonable costs (Tab. 2) . A cantonally or nationally organized screening program as for breast carcinoma should be aimed for.

Literature:

- Federal Office for Statistics

- Vogelstein B, et al: Genetic alteratons during colorectal-tumor development. NEJM 1988; 319: 525-532.

- Hewitson P, et al: Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 1: CD001216.

- Whitlock EP, et al: Screening for colorectal cancer. A targeted, updated systemic review fort he U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149: 638-658.

- Atkin WS, et al: Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 375: 1624-1633.

- Schoen RE, et al: Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. NEJM 2012; 366: 2345-2357.

- Elmunzer BJ, et al: Effect of Flexible Sigmoidoscopy-Based Screening on Incidence and Mortality of Colorectal Cancer: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials; PLoS Med 9(12): e1001352.

- Dodou D, de Winter JC: The relationship between distal and proximal colonic neoplasia: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27: 361-370.

- Levin B, et al: Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology 2008; 134: 1570-1595.

- Winawer SJ, et al: Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. NEJM 1993; 329: 1977-1981.

- NCCN guidelines for colorectal cancer screening, version 1.2014; American College of Gastroenterology 2009 guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 739; American Cancer Society (recommendations for colorectal early cancer detection); ESMO, ASCO.

- www.krebsliga.ch/de/praevention/pravention_krebsarten/darmkrebs/fruherkennung

- Misselwitz B, et al: DNA methylation and colon cancer screening. Schweiz Med Forum 2011; 11(6): 103-107.

- Walther A, et al: Genetic prognostic and predictive markers in colorectal cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2009; 9(7): 489-499.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(8): 7-10.