Antibiotics are regularly used in the treatment of COPD patients with acute exacerbations (AECOPD) – too regularly, if you take a look at the guidelines. These recommend its use only under certain conditions. An expert at the DGP explained when this is the case and what else needs to be considered.

In patients with stable COPD, potentially pathogenic bacteria can be detected in sputum in up to 25% of cases, which is usually considered colonization. In acute exacerbation, as far as sputum is presented, we can detect potentially pathogenic agents in up to 50% of cases, but the clinical relevance is questionable, precisely because a relevant part represents chronic colonization and is not associated with AE at all. “The bottom line is that we assume that AECOPD is really associated with a bacterial or viral genesis in only 25% of cases,” said Dr. Holger Flick, Clinical Division of Pulmonology, University Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University of Graz (A), by way of introduction.

On the efficacy of antibiotic therapies in outpatients with COPD exacerbations, there are 4-5 relevant studies, which, according to the pulmonologist, have yielded one major finding: “With antibiotics, we have slightly less treatment failure, but the difference is limited.” For amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, this is 22-26% vs. placebo 40%; moxifloxacin was 21% vs. Placebo. Dutch studies also found slightly less treatment failure after 10-21 days (doxycycline 20-21% vs. placebo 31%; in one study, there was no difference at all between the antibiotic and placebo groups after 30 days. Overall, however, no mortality benefit was observed.

More convincing in the clinic

In the hospitalized area, the whole picture looks somewhat more convincing: Here, a significant reduction in mortality can even be observed with regard to antibiotic therapy. In this regard, Dr. Flick referred to data from two meta-analyses that found a reduction in antibiotic use in hospitalized patients with AECOPD with an RR of 0.22 (95% CI 0.08-0.62) and a reduction in treatment failure with an RR of 0.77 (95% CI 0.65-0.91). There was also evidence of an effect on antibiotic use in ICU patients with AECOPD (reduction in mortality: OR 0.21; 95% CI 0.06-0.72; reduction in treatment failure: RR 0.19; 95% CI 0.08-0.45).

Ultimately, the questions that arise from all of these data are: are there certain patients who would particularly benefit from antibiotics in the office-based setting? Or – despite the stronger evidence – are there hospitalized patients who can ultimately be treated safely and successfully without antibiotic therapy?

There is a European audit on the subject from 2015. According to the study, the average of antibiotic prescriptions for COPD exacerbations in hospitals is 86%, while the average of guideline-based antibiotic prescriptions in Europe is only 61%. The handling of antibiotics varies greatly from country to country: in Central Europe, on average, fewer antibiotics are used and treatment tends to follow the guidelines, whereas in countries such as Spain or the United Kingdom, there is obviously less adherence to the guidelines.

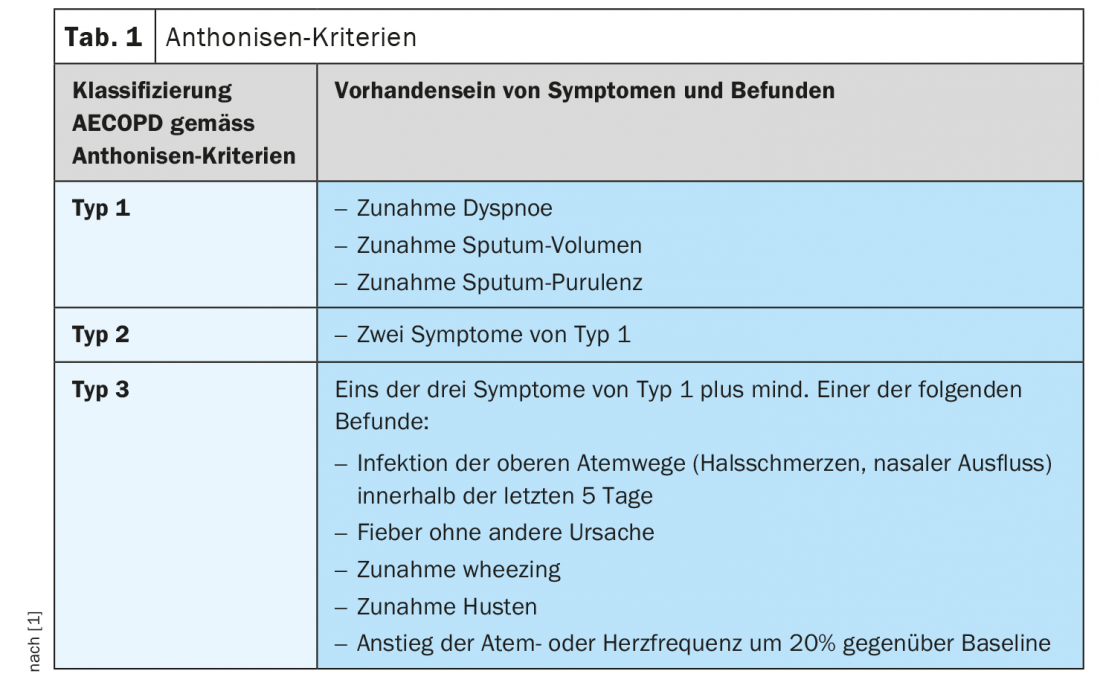

In essence, guideline-compliant means applying the GOLD criteria, which in turn are based on the Anthonisen criteria, based on the 1987 Winnipeg study. Anthonisen criteria essentially amount to an increase in three symptoms: increase in dyspnea, increase in sputum volume, and increase in sputum purulence or new sputum purulence. Depending on whether one, two, or all three of these core criteria are had, AECOPD is classified as type 1, 2, or 3 (Table 1) .

Color of sputum is central factor

Sputum purulence is by all means a delicate factor, because the question always arises: How does one actually determine this? In studies (including the Winnipeg study), the whole thing was determined with the help of a color scale. “That’s very important, because if you don’t do it based on the scale, you have much less validity” cautioned Dr. Flick. When patients are asked how they define the color of their sputum, only 47% of the data on yellow, for example, match the color scale. Even the doctor estimates it correctly only in 50% of cases. The situation is even worse in the case of green sputum: Here, the correct indication on the part of the patients is 10%, and among the physicians even only 9%. The color scale has a relatively good correlation with proven bacterial pathogens in sputum, with a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of only 52%. However, if the scale is not used and only the patient is asked for his subjective assessment, the sensitivity drops to 73% and the specificity is only 39%. “Ultimately, it has to be said: If we treat patients with yellow or green sputum – in most cases probably reported so by the patients or assessed so by the physician without comparing the color scale – then we basically treat half of them pointlessly with an antibiotic, because there are actually no pathogens there at all,” is the expert’s less than positive conclusion.

|

Swiss recommendations Switzerland has an approach that differs somewhat from the German guideline [3]: In this country, it is recommended that antibiotics always be used in the intensive care setting. For the remaining patients, one can follow the anthonisen criteria, but in addition, one can also follow CRP (cut-off 50 mg/dl) or PCT (cut-off 0.25 μg/l). |

Current recommendations of the DGP

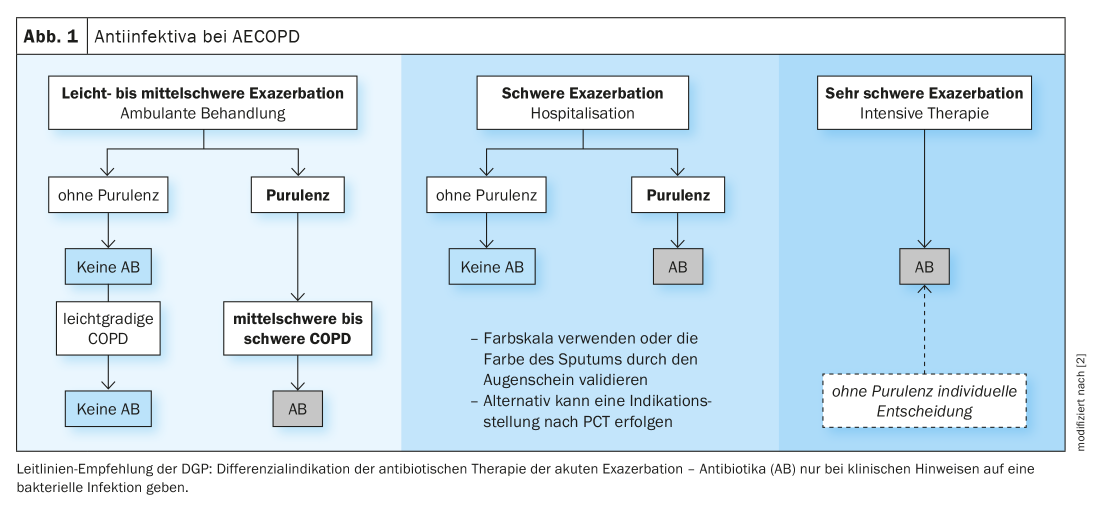

Anti-infectives are, of course, only a small part of COPD therapy. Antibiotics should be used only when there is clinical evidence of bacterial infection. The German Society for Pneumology and Respiratory Medicine (DGP) primarily recommends orientation to sputum purulence here. In this regard, the current 2018 S2k guideline states that the purulent sputum criterion is the best predictor of culturally/bacterially positive sputa. Thus, indication by purulent sputum appears to be the most reliable clinical predictor of the presence of bacterial pathogens. Only in very severe exacerbations is the use of antibiotics recommended regardless of sputum purulence or other biomarkers (Fig. 1).

PCT and CRP are also discussed, but there is some reluctance to do so. In one study, predefined cutoff values for PCT did reduce the rate of antibiotic therapy without drawbacks, but the data showed no association with anthonisen criteria, so it remains unclear what the PCT actually indicated, Dr. Flick said. With regard to CRP, there are contradictory data: Some studies found a value between 19 and 40 mg/l to be predictive of bacterial pathogens, but in other studies no cut-off value could be defined.

The drug of choice for antibiotic therapy is amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (or amoxicillin mono); macrolides or doxycycline may be considered as alternatives for moderate exacerbations. In severe or very severe exacerbations, quinolones (moxi-/levofloxacin) may be given as an alternative. However, Dr. Flick referred to the warnings of the EMA, among others, that quinolones should only be used in justified exceptions. In the case of macrolides and amoxicillin (without BLI), it is important to take into account known weaknesses in efficacy against H. influenzae and Moraxella, respectively. Therapy duration is 5-7 days each.

Take-Home Messages

- In multifactorial disease, antibiotics can be a component of therapy but have limited impact on the course of AECOPD.

- Very severe AECOPD (ICU) should always be treated with antibiotics.

- For outpatients and inpatients, several factors should be considered in the decision-making process:

- Classic criteria (sputum purulence –> color chart).

- Laboratory chemistry parameters (CRP or PCT –> helpful, safe, and practical).

- Clinical factors in synopsis of the current situation and previous history

Source: Lecture “COPD – Antibiotic therapy, what is recommended: guidelines and current developments including resistance situation” in the session “Antibiotics in COPD: Who does it benefit, who does it harm?”. 61st Congress of the German Society for Pneumology and Respiratory Medicine e.V., 5.06.2021.

Congress: DGP 2021 digital

Literature:

- Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, et al: Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1987; 106: 196-204.

- Vogelmeier C, Buhl R, Burghuber O, et al: S2k guideline on diagnosis and treatment of patients with chronic obstructive bronchitis and emphysema (COPD). Pneumology 2018; 72: 253-308.

- Buess M, Schilter D, Schneider T, et al: Treatment of COPD exacerbation in Switzerland: Results and Recommendations of the European COPD Audit. Respiration 2017; 94 (4): 355-365; doi: 10.1159/000477911.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2021; 3(3): 18-20.