In addition to common gastroenteritis and upper respiratory tract infections, many pediatric emergencies in family practice involve pain. Dr. med. Nina Notter, senior physician mbF Ostschweizer Kinderspital and medical director of the pediatric practice Buchs (SG), gives an insight into the most common diseases, the special examination techniques and possible therapies.

As a doctor for the whole family, the family doctor is also in demand for the care of children. According to Notter, the most common causes of consultations are fever, mouth, throat and ear disorders, respiratory problems, abdominal pain, lice/worms, skin conditions and musculoskeletal complaints. They are usually emergencies related to pain [1].

Streptococcus A tonsillitis

Streptococcal A tonsillitis is characterized by sore throat and fever. Bacterial infection does not cause rhinitis, cough, hoarseness, or conjunctivitis. These accompanying symptoms are indicative of a viral infection. Eventually, cervical lymphadenopathy may occur, and abdominal pain and vomiting are not uncommon. If, in addition, a fine macular, bright red exanthema is diagnosed, which feels like fine sandpaper and usually begins inguinally, as well as lacquer lips and the typical strawberry tongue, it is scarlet fever. However, at age <3 years, streptococcal A tonsillitis is uncommon, so diagnostic restraint is recommended.

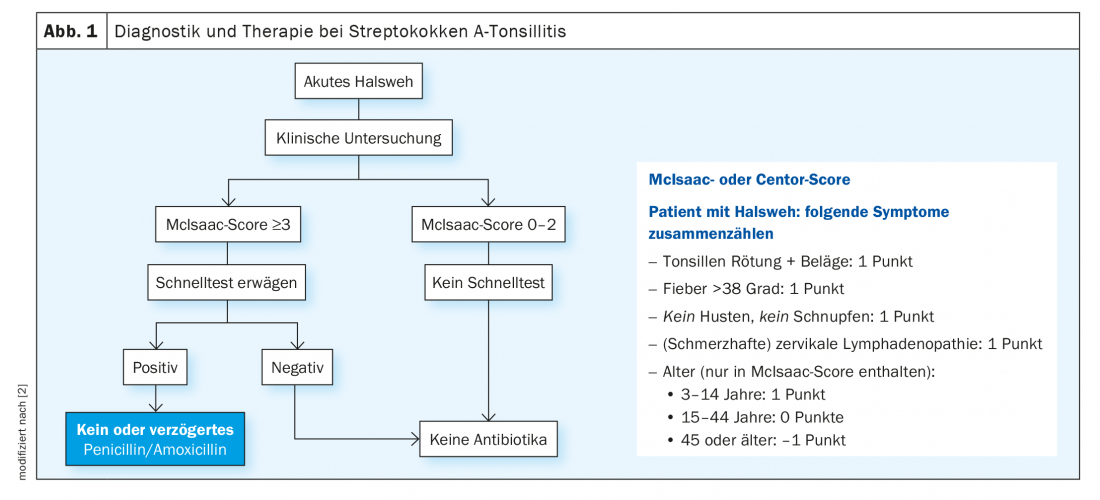

According to previous recommendations, streptococcal A tonsillitis should always be treated with antibiotics to prevent post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis or arthritis and local purulent complications. Meanwhile, studies have shown that not using primary antibiotic therapy with good follow-up, does not increase the risk of this. In addition, the main reasons for antibiotic treatment included acute rheumatic fever, but this no longer occurs in Central Europe with strains of group A streptococci. Accordingly, the number needed to treat (NNT) for prevention of RF/local complications has increased such that primary antibiotic therapy is no longer warranted. Instead, the clinical examination now includes the use of the McIsaac score. If the McIsaac score is <3, no further diagnostic testing is recommended unless there is a specific reason for doing so. If the McIsaac score is ≥3, a throat swab/rapid test may be considered, although no penicillin/amoxicillin or only delayed penicillin is recommended even if the test result is positive (Fig. 1) [2]. Antibiotic therapy should be given only with amoxicillin (25 mg/kgKG p.o. 2×/day for 6 days) and generally only in cases of poor general condition, high distress, risk factors such as immunosuppression or acute rheumatic fever, reevaluation in case of unusual course or lack of improvement within four to seven days. An individual decision should be made for young children or recent immigrants. Otherwise, therapy consists of the administration of systemic analgesics/antipyretics; topical or disinfectant local anesthetics may also be used.

Balanitis

Balanitis/balanoposthitis often occurs between 2 and 5 years of age and in association with phimosis. It is characterized by redness and swelling as well as pain and itching of the glans and prepuce. Alguria is not uncommon. However, depending on the pathogen, a purulent discharge or a blotchy rash in the genital area may also occur. Infectious forms caused by staphylococci or group A streptococci are most common. However, balanitis can also occur as a result of herpes simplex virus, diaper thrush, and in sexually active adolescents. Noninfectious balanitis is found primarily in lichen sclerosus et atrophicans (balantitis xerotica obliterans).

The therapy consists of analgesia. Good hygiene without soap is recommended and retraction only in the absence of phimosis or marked swelling. In addition, local ointment treatment with Vaseline, for example, is possible, as well as sitz baths with synthetic tanning agents or disinfecting sitz baths. If the findings are more pronounced, there is the possibility of local antibiotic therapy with fusidic acid. If fever or inguinal lymphadenopathy occurs, systemic antibiotic treatment may be necessary. Circumcision is recommended for recurrent balanitis or lichen sclerosus et atrophicans .

Vulvitis

The peak age of vulvitis is similar to balanitis and ranges from 2 to 7 years. The reason for this is the very low estrogen level at this age, which makes the genital mucosa susceptible to disease. Vulvitis is basically characterized by fluor vaginalis, possibly with maceration and unpleasant odor. Itching and redness and possibly purulent efflorescences are common with group A streptococci. In addition, dysuria, pain, burning, or bleeding may occur. The causes of vulvitis are usually non-specific inflammatory. Mostly it is a chemical or mechanical irritation caused by wet wipes, diapers as well as panty liners or even foreign bodies. Furthermore, vulvitis may occur due to atopic dermatitis or concomitant with viral/bacterial infection. Specific inflammatory causes may include lichen sclerosus et atrophicans or psoriasis.

Infectious vulvitis is age-specific: in neonates/infants, it is caused either by Candida albicans (diaper thrush) or vertically transmitted pathogens from the mother, such as. Chlamydia trachomatis or HPV; prepubertal causes are more likely to be bacterial (group A streptococci, intestinal flora, Haemophilus) or caused by molluscs, systemic viral infection, and oxyuria; pubertal vulvitis is both bacterial and caused by Candida albicans, Herpes simplex virus type 1/2 or sexually transmitted pathogens causes.

Diagnosis is made by clinical examination and generally takes place externally. If a vaginal examination is necessary, it should be performed exclusively by the gynecologist. Pathogen testing is rarely necessary. It is performed only if there is bacterial vulvitis with severe redness, swelling, and pain or if the child is on corticosteriod therapy. In this case, the pathogen search should be performed by aspirate bacteriology, not by smear. In addition, for sexually active adolescents, chlamydia and gonococcal PCR can be performed.

Therapy includes general hygiene measures (use of children and footstool for toilet, cleaning from front to back after defecation), avoidance of excessive genital hygiene (daily cleaning with water only), sitz baths with baking soda (one sachet to five liters of water) or sea salt, and local care with Vaseline or olive oil (possibly nourishing oils in the bath water). The specific therapy depends on the pathogen identified: In the case of Candida albicans Infants receive clotrimazole locally, in adolescence clotrimazole is administered vaginal ovoules if necessary fluconazole in case of recurrence or problems with insertion; for group A streptococci the same therapy is given as for angina; oxyuras are treated with either mebendazole or pyrantel, observing the hygienic measures; for the Lichen sclerosus et atrophicans local therapy with corticosteroids is recommended during the acute phase; after the acute phase has subsided, moisturizing care is sufficient as maintenance therapy. Referral to a pediatric gynecologist should be made only in cases of prolonged problems, bloody discharge or recurrence within four weeks, after adequate treatment, and if sexual abuse is suspected.

Benign nocturnal leg pain (“growing pains”)

The so-called “growing pains” usually occur in children <6 years. In older children, these are generally also possible, but differential diagnoses should predominantly be considered. A typical feature of benign leg pain is that it occurs mainly in the evening or at night; during the day, affected children are often symptom-free. The course of pain is usually alternating or phasic and it occurs bilaterally or alternately. There should be no visible redness or swelling and there should be no dependence on exertion, that is, the pain does not occur with or immediately after exertion.

The medical history can usually be used to assess whether further diagnostics are necessary. Scher usually asks about the location of the pain. This is not always the same and is often indicated on the lower/front of the thigh, calves, back of the knee, or the top of the foot. Furthermore, the query is made after overload or trauma and increased physical activity. In connection with the general condition, fever or other signs of infection should also be clarified. Indications of restless legs syndrome (restlessness, tingling, urge to move) should also be taken into account, as well as inquiries about previous hematological diseases and autoimmune/metabolic diseases. Depending on the findings, clinical examination should include assessment of legs and joints as well as general status including lymph nodes, liver/spleen size, skin, neuro status, etc. Atypical presentations can be further clarified by laboratory and imaging. Differential diagnoses include inflammatory diseases (osteoarticular infection, arthritides), benign tumors, malignancies (localized bone pain often also at night), leukemia, metabolic or endocrinologic diseases (may lead directly to musculoskeletal complaints), or growth-related and traumatic musculoskeletal injuries.

A therapy considers besides massages, local ointment applications or individual local heat/cold also the education of the families about the benign mostly self-limiting course. In exceptional cases, paracetamol or NSAIDs may be administered, but this should not be the rule.

Congress: FomF General Internal Medicine Update Refresher

Literature:

- Nina Notter, MD: Common “childhood diseases” in family practice. General Internal Medicine Update Refresher, FomF, 5/17/2022.

- Berger H, et al: Treatment of streptococcal angina without antibiotics. Prim Hosp Care Allg Inn Med 2021; doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/phc-d.2021.20037.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(7): 28-29