Patients with complaints of dizziness often report primarily to their primary care physician, giving general practitioners an important triage role. Here, history and clinical examination should first aim to distinguish serious forms of vertigo, such as central vestibular disorders, from harmless forms of vertigo.

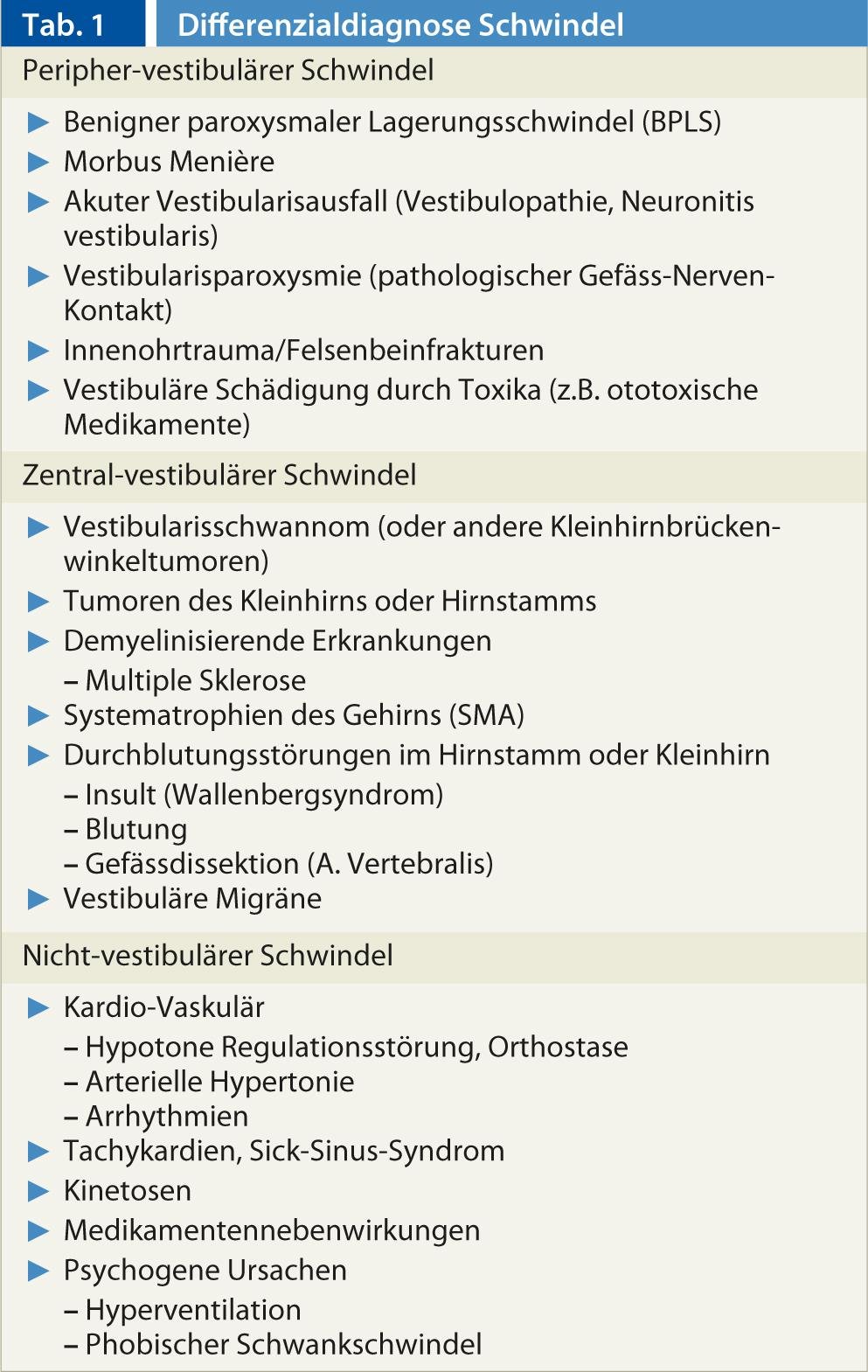

The symptom of dizziness can have many different underlying causes (Tab. 1), which is why it is often difficult to make a correct diagnosis. Key to diagnosis is a careful history taking and physical examination. Further apparative as well as imaging examinations are necessary in selected cases, but should be critically indicated.

Medical history

Type of vertigo: The term “vertigo” is used for a variety of conditions, so the type of vertigo must be asked precisely. If spinning dizziness is present, you feel like you’re on a merry-go-round – everything is spinning. With staggering vertigo, you feel like you’re on a ship. Furthermore, dizziness may be perceived as a diffuse feeling of insecurity, drunkenness, or lightheadedness (blackness before the eyes). Some patients describe diffuse head pressure.

Duration of dizziness: Does the dizziness occur in fits and starts? If so, how long do the attacks last? Seconds, minutes, hours or days? Is there a persistent dizziness?

Triggerability/aggravation of vertigo: Does the vertigo already exist at rest? Does it occur when standing up? Does the dizziness exist only when standing or when walking? Does insecurity increase in the dark or on uneven surfaces? Was a new medication prescribed promptly to the initial onset of vertigo? Can the vertigo attacks be triggered by a specific movement (e.g., turning in bed), noise, pushing, or some other factor?

Associated symptoms: Are there accompanying symptoms such as headaches, visual disturbances, swallowing or speech problems, hyp- and dysesthesias? Are ear symptoms (hearing loss, tinnitus, otalgia and otorrhea) present? Does the patient experience palpitations or an irregular pulse?

Medications and known diseases: What medications are being taken? Are there any known diseases (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, migraine, etc.)?

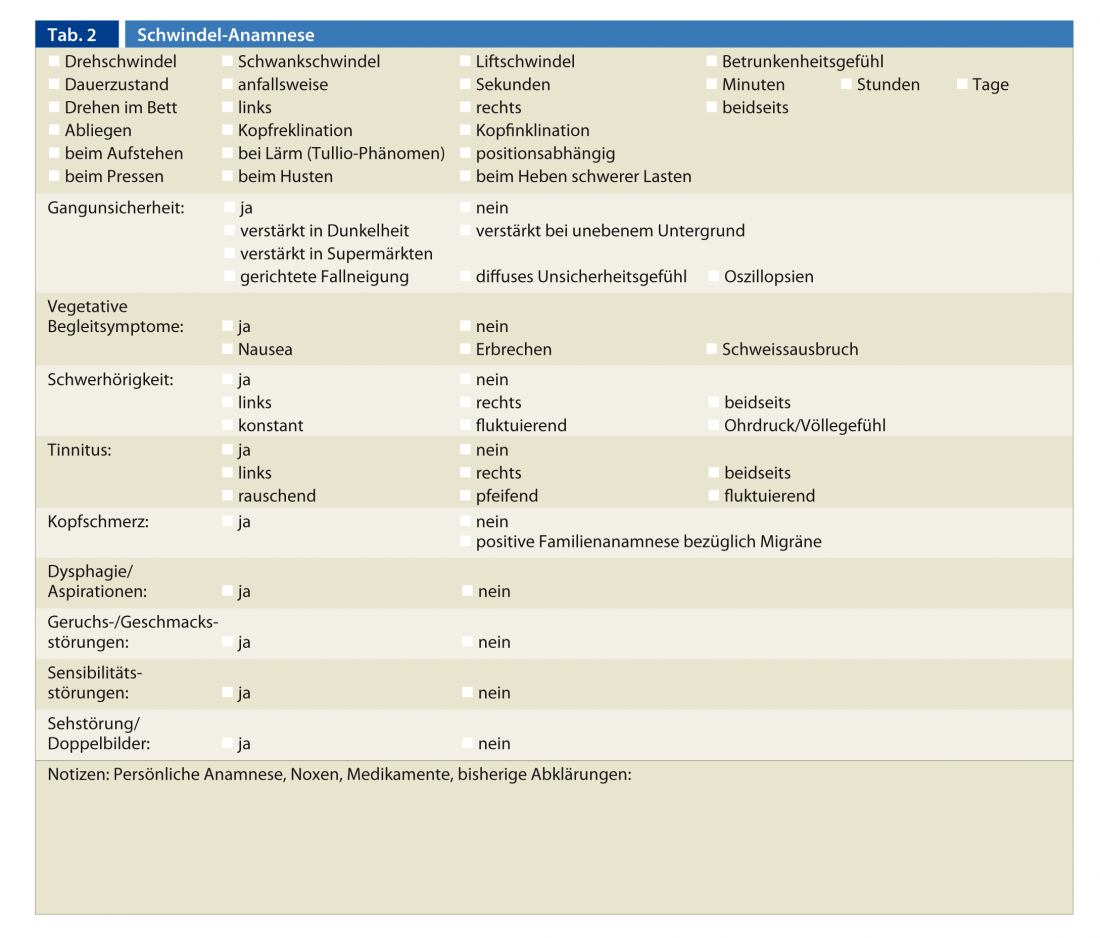

To avoid duplications, it is advisable to ask whether clarifications have already been made. It is helpful to conduct the survey with a medical history sheet to ensure speedy work (Tab. 2).

Differential diagnostic considerations based on the medical history

If the patient reports rotary vertigo, a vestibular disorder is most likely. If the seizures are of seconds duration, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPLS) is suggestive. If, on the other hand, the attacks last several hours, Meniere’s disease and vestibular migraine must be considered as differential diagnoses. If continuous spinning vertigo persists for two to three days, acute peripheral vestibular dysfunction or a central event may be considered. If accompanying neurological symptoms are present in addition to the dizziness, a central cause is suspected. Dizziness that occurs only in the upright position or during physical exertion, or with syncope or dizziness. presyncope is most likely to be of cardiovascular origin.

Clinical examination

Depending on the history and corresponding differential diagnosis, the focus of the status is placed on the internal or neurological-vestibular examination. From the internal medicine side, the focus is usually on cardiovascular assessment (auscultation, BP measurement, ECG, etc.).

The clinical vestibular examination

Examination with Frenzel spectacles: Frenzel spectacles are equipped with highly refractive, concave magnifying lenses that have a refractive power of +15 to +18 diopters. They thus prevent sharp vision. This interrupts the patient’s visual contact with objects in the environment and thus eliminates any possibility of visual fixation. In addition, the glasses are illuminated inside, while the examination takes place in a darkened room. The illumination and magnification of the eyes through the lenses facilitate the assessment of eye movements by the examining physician.

Frenzel glasses are used to observe involuntary eye movements (nystagmus). Nystagmus refers to the uncontrollable, rhythmic movements of an organ, but usually the eyes, so nystagmus is usually understood to mean eye tremor. In “jerk nystagmus”, a slow initial movement and a fast resetting movement are found. The direction of nystagmus is indicated after the fast phase, because it is easier to recognize. Horizontal flapping patterns are most common, but vertical and rotational forms also occur.

If a nystagmus is present when looking straight ahead without external stimuli from the visual and vestibular systems, it is a spontaneous nystagmus. The gaze direction nystagmus is sought when looking 30° to the left and to the right, upward or downward, and points in each case in the corresponding direction of gaze.

A peripheral vestibular nystagmus beats in the same direction for all gaze directions, increasing in intensity when looking in the direction of the fast phase and decreasing in intensity when looking in the opposite direction (Alexander’s law). Visual fixation can suppress or at least slow down peripheral vestibular nystagmus.

A vertically upward or downward (up- or downbeat) beating spontaneous nystagmus as well as gaze direction nystagmus are always of central genesis. Equally centrally conditioned is a fixation occurring resp. nystagmus that intensifies with fixation or cannot be stopped. In these cases, further clarification is required immediately.

If no spontaneous or gaze direction nystagmus is found, a head shaking nystagmus must be looked for. Here, the patient’s head is shaken back and forth in the horizontal plane by the examiner for about ten seconds at a frequency of about 2 Hz.

Head shaking nystagmus is found in peripheral vestibular dysfunction that is not fully compensated centrally. These patients typically report increased uncertainty in the dark resp. during rapid movements.

Positional test: If there is a suspicion of BPLS with attacks of rotatory vertigo lasting for seconds, a positional test must be performed. Frenzel glasses should also be used during this examination. The various archways are tested separately.

The posterior archway is tested with the Dix-Hallpike maneuver (Fig. 1).

The patient’s head is rotated 45° to the side, then the patient is placed in the head hanging position. If BPLS is present, a geotropic (i.e., directed toward the arc) rotating nystagmus with an additional upbeat component occurs with a latency of a few seconds. Typically, a crescendo-decrescendo phenomenon is found, usually the nystagmus subsides after ten to 30 seconds. After rapid righting, a nystagmus beating in the opposite direction is found.

The horizontal arcade, which is affected in about 20% in BPLS, is examined with the so-called Pagnini-McClure test. The patient lies on the examination couch with the upper body raised 30°. In this position, the head is rotated jerkily to one side and then to the other. If BPLS is present, geotropic nystagmus is found bilaterally, also with crescendo-decrescendo phenomenon. The side that reacts more strongly is the one that is diseased.

The BPSL of the posterior arcuate is treated with the Epley or Semont maneuver, and the BPLS of the horizontal arcuate with the Gufoni or Barbecue maneuver.

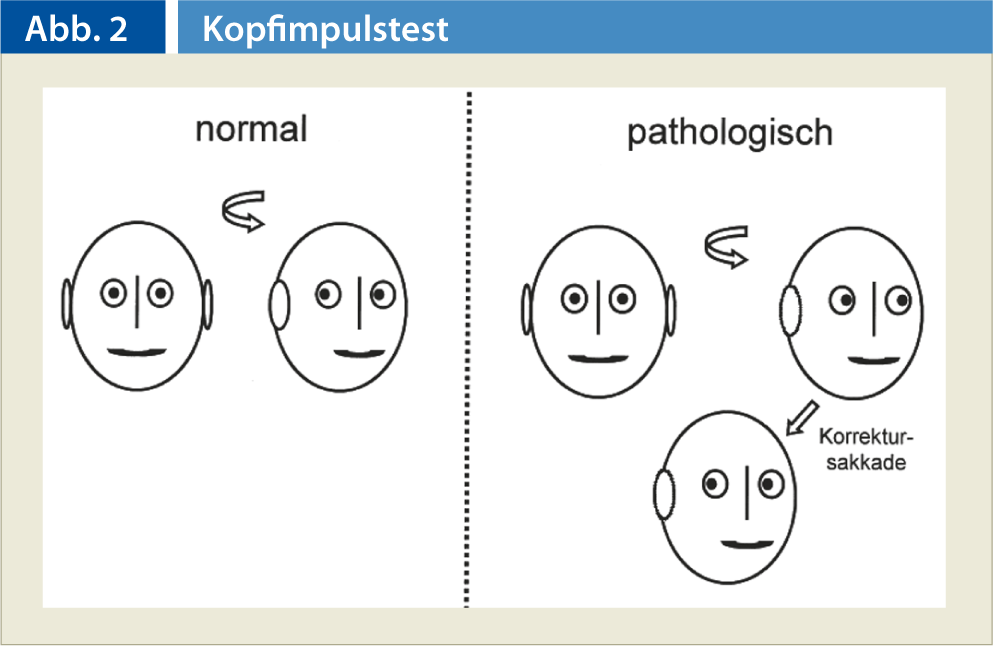

Head Impulse Test (KIT): The KIT is used to examine the vestibulo-ocular reflex. This sensitive test allows unilateral or bilateral peripheral vestibular hypofunction to be detected by inspection. The examiner sits in front of the patient and grasps the patient’s head firmly from both sides at the temple. The patient is asked to fixate the tip of the examiner’s nose. The examiner jerkily turns the patient’s head about 10 to 15° to the right or left. With normal vestibular function, the patient’s eye always remains focused on the nose. If, on the other hand, there is a dysfunction, the eye deviates to the side together with the head, immediately followed by a corrective saccade in the opposite direction to re-fix the tip of the examiner’s nose (Fig. 2).

Clinical balance test

Romberg test: In the Romberg test, the patient is asked to stand upright with feet together and eyes closed. Often, the test is combined with the hold-forward test, in which both arms are extended forward.

Underhill tread test: The patient treads evenly on one spot with eyes closed. It is important that there are no landmarks (bright light sources, ticking clocks) in the room. The test is considered positive, i.e. conspicuous, if the patient turns more than 45° from the starting position during 50 steps.

Tandemromberg: In this test, the feet are placed one behind the other. The test is performed with the eyes open and closed. If the patient can maintain stable balance for ten seconds, the test is passed.

One-leg stand: The patient must try to stand stably for ten seconds, first with eyes open, then with eyes closed.

Age-appropriate normal balance is present when a patient under the age of 40 can complete the one-leg stand with eyes closed. Patients over 60 should be able to stand on one leg with their eyes open. For 40- to 60-year-olds, the tandemromberg should still be possible with eyes closed.

If the examination shows that balance is much worse with eyes closed than with eyes open, a peripheral vestibular disorder (centrally uncompensated unilateral disorder or bilateral vestibulopathy) as well as polyneuropathy with decreased depth sensitivity must be considered as a differential diagnosis. An easy-to-perform orienting test concerning polyneuropathy is the examination of the sense of vibration at the malleolus with the corresponding tuning fork.

Coordination testing: Orientationally, coordination can be tested using the finger-nose and knee-hook tests as well as diadochokinesis. In addition, a gait test (normal, blind, and dash gait) should be performed to identify an ataxic gait pattern in particular. If a small-stepped gait is found, the V.a. a Parkinson’s syndrome exists, so that among other things a cogwheel phenomenon must be looked for.

Cranial nerve status: Trigeminal and facial function can be tested clinically very easily. In addition to testing oculomotor function, the presence of anisocoria or Horner’s syndrome must be looked for. Since the caudal cranial nerves may be affected, especially in the case of pathologies in the brainstem area (e.g. Wallenberg syndrome), an appropriate examination is necessary. The hypoglossal nerve can be tested by sticking out and moving the tongue back and forth. If glossopharyngeal paresis is present, there is asymmetric distortion of the soft palate, i.e., deviation of the uvula to the healthy side during phonation. In addition to hoarseness (paresis of the recurrent nerve), vagus paresis leads to a backdrop phenomenon.

If signs of cranial nerve involvement are found, a central cause must be assumed and further clarification by the specialist must be initiated accordingly.

If the patient reports ear symptoms, a Weber and Rinne tuning fork examination and otoscopy must be performed. In particular, the aim is to exclude acute otitis media with inner ear involvement as well as zoster oticus.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The clinical examination possibilities in practice are manifold; on the basis of the listed examinations the diagnosis can be made in very many cases or at least the differential diagnosis can be strongly limited.

- The type of dizziness, duration, triggering, intensification and accompanying symptoms of the dizziness are just as much a part of a careful medical history as medication intake and already known illnesses.

- In case of signs of cranial nerve involvement or vertical nystagmus, a central cause must be assumed and further clarification must be initiated accordingly.

Bibliography with the author

Marcel Gärtner, MD