Pain psychotherapy includes both a symptom-oriented and problem-oriented approach. Psychosocial and workplace factors contribute to chronification and are essential to consider in therapy. Eduction is an important component in promoting coping and compliance.

Back pain is a significant health disorder in Western industrialized nations. In the survey by Schmidt et al. [1], 76% of respondents reported back pain in the past 12 months. Across studies [2], the following aspects can be noted: Women are affected more often than men, back pain is found in all age groups and all social classes, young adults show a high annual prevalence already from 20 years of age, the prevalence of chronic back pain increases with age. A high recurrence rate combined with a tendency to chronicity make back pain a health and sociopolitical problem, as the chronicity of the complaints is associated with increasing socio-medical consequences such as reduced incapacity to work and disability, but also utilization of medical services.

Definition and symptomatology

The underlying causes or pathomechanisms of back pain include a large number of disease processes. However, specific diseases, such as a herniated disc or inflammatory processes, represent the pathological basis in only a few of the cases. The vast majority of back pain is referred to as “non-specific” back pain. In 80-90%, the exact cause remains unclear; in addition to degenerative changes, functional disorders affecting the intervertebral discs, muscles, fasciae, ligaments, and vertebral arch joints are found [3]. Non-specific means that no or only irrelevant structural pathological findings can be found for the pain symptomatology.

Chronifying factors

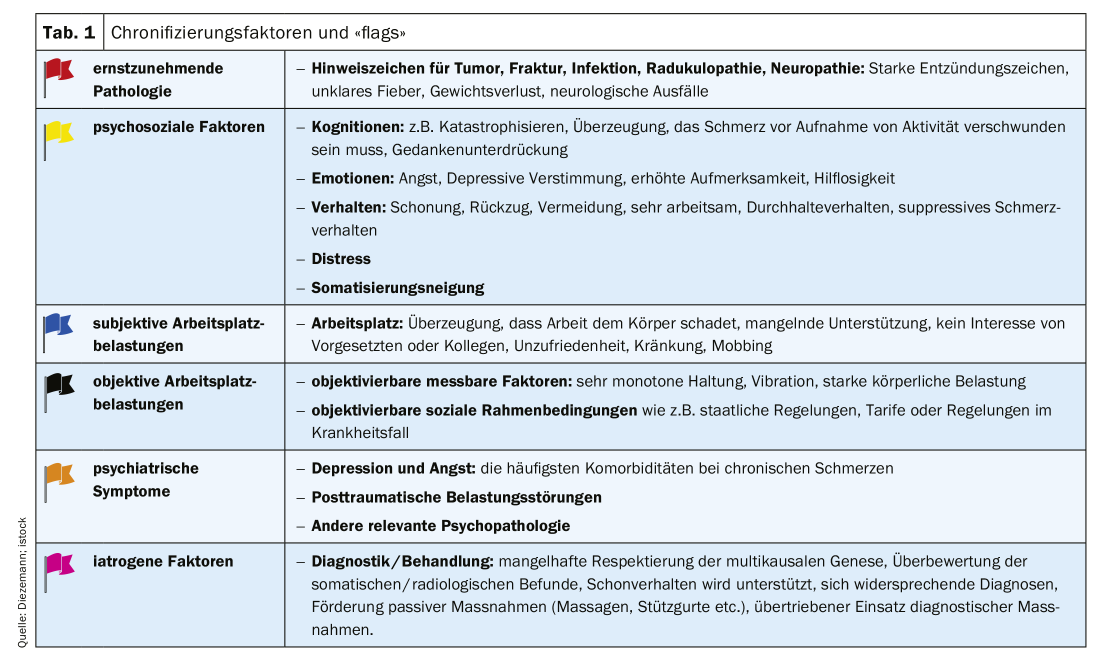

The purely medical view and therapy of back pain repeatedly reaches its limits, as other important influencing factors in the process of chronification are neglected. The so-called “flags” in Table 1 describe these risk factors comprehensively [4].

Workplace characteristics (“black flags”) such as heavy physical labor, vibration stress, and prolonged constant body positions are described as prognostically unfavorable. However, there are doubts about a direct link between objective workplace conditions and the occurrence of back pain: the prevalence of back pain in industrialized nations is rising, even though ergonomic workplace conditions are increasingly improving. However, relevant risk factors for the chronification of complaints are primarily characteristics such as the subjectively experienced workplace stress (“blue flags”) and psychosocial factors (“yellow flags”), dysfunctional coping strategies and also emotional reactions to the complaints (anxiety, depression) [5].

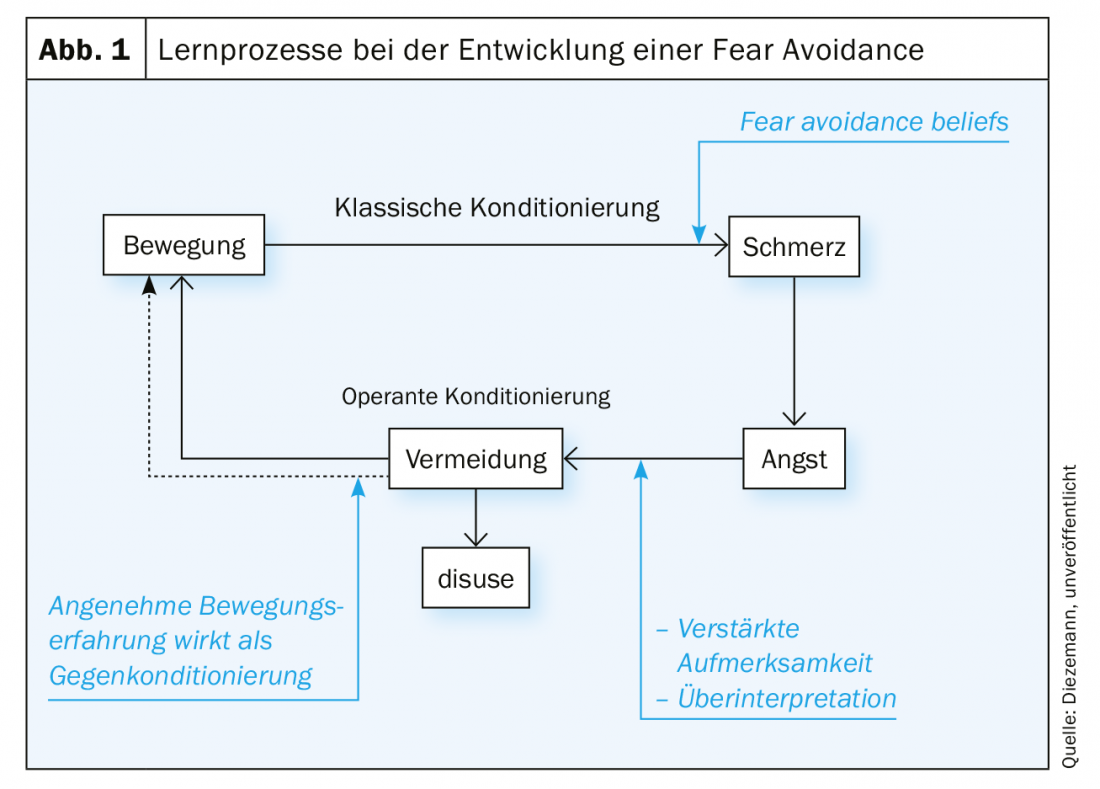

The subjectively experienced handicap of the patient (disability) and the perception of the nature and treatability of the disease, the patient’s own possibilities of influence and the associated illness behavior (passivity, sparing, inability to work, use of the health care system) represent significant perpetuating factors of the complaints. If the patient is convinced that their discomfort signals a physical hazard and is a result of physical exertion, they will avoid exertion in the future to prevent further potential physical harm and pain exacerbation. A so-called fear-avoidance behavior develops out of fear of pain and of being harmed. In terms of learning theory, this can be explained as follows: The cognitively mediated association between pain and physical stress arises from classical conditioning and is operantly reinforced by fear-motivated avoidance behavior (Fig. 1).

With increasing inactivity comes loss of mobility, coordination problems, deconditioning, poor posture, and weakness of the musculature (atrophy) [6]. The controlled movements (guarded movement) associated with fear-avoidance behavior lead to nonphysiological movement patterns, increased self-awareness, and increased muscle tension. This behavior tends to be reinforced by classical back schools, in which the patient is “trained” to follow certain movement patterns. For example, the patient learns to bend at the knees when picking up only light objects. Here, patients describe a feeling of moving very stiffly and deliberately, as if in a corset. During behavioral observation, these movement patterns are also apparent.

In addition to these specific fear avoidance beliefs in back pain patients, other unfavorable pain-related cognitions can be identified as risk factors. External control attributions (“only surgery can help me”), pronounced stable causal attributions (“my spine is in shambles, nothing can be done about it”), and the tendency to catastrophize (“the pain will get worse and worse and I will become a nursing case”) represent the most common maladaptive thought patterns here. The experience of helplessness and hopelessness associated with such thoughts in turn fosters protective and avoidant behavior and rather passive coping strategies. Increasing withdrawal, existing inability to work, and helplessness can increase depressive moods and anxiety. There is a loss of the existing social role (e.g. as the breadwinner of the family), conflicts within the family and with the social environment. Self-esteem can change, daily routines are increasingly determined by “managing” the pain.

In contrast, another group of patients is more likely to exhibit perseverative behavior, exhibit high performance demands, and repeatedly exceed physical performance limits, which also contributes to chronification. Often there are double burdens (several jobs, single parent, family members have to be cared for), which favor this dysfunctional coping. These patients often have a poor perception of stress, some trivialize the symptoms and also use analgesics to function in everyday life. A distinction is made between the “depressed holdouts,” who often describe a depressed-irritated mood because the day-to-day demands of chronic pain are almost impossible to manage, but they “muddle through,” and the “cheerful holdouts,” who use injections and medications to function and often show little awareness of the problem. Sometimes, however, it is more of a “poker face”, the person concerned puts on a happy face because the professional or family context demands it, but the mood is actually clearly affected. Patients with such perseverance often overexert themselves for years until they are increasingly forced into rest due to exhaustion and eventually then become incapacitated for work in the long term. The physical performance decreases more and more with time, because the body does not have enough time to regenerate until the next activity.

In addition to these psychosocial factors (yellow flags), the so-called iatrogenic chronification (“pink flags”) [7] plays an essential role. Iatrogenic means: harmful influences, resulting from therapeutic behavior and non-behavior. The medical care system supports the patient’s lay conceptions of disease; local pathology and purely medical treatment options are overemphasized, while psychosocial factors are neglected.

In addition, there are regional labor market conditions that make re-integration into working life unlikely if the person has poor qualifications and is impaired by the back problems. With a longer period of illness, considerations of applying for a pension then become more likely. The interaction of the psychological-social and somatic consequences of the complaints leads in the sense of a vicious circle to the further maintenance of the complaints.

Therapy

In Germany, the Barmer Ersatzkasse describes in its 2015 report a comparison of therapy in 2006 with 2014: despite updating the National Health Care Guideline for Low Back Pain in 2017, there was a rate of increase in interventional pain therapy. Multimodal therapy has quadrupled, but the ratio of interventional pain management versus interdisciplinary multimodal pain management is 11:1. Overall, there is misuse, underuse and overuse of care for chronic back pain in Germany.

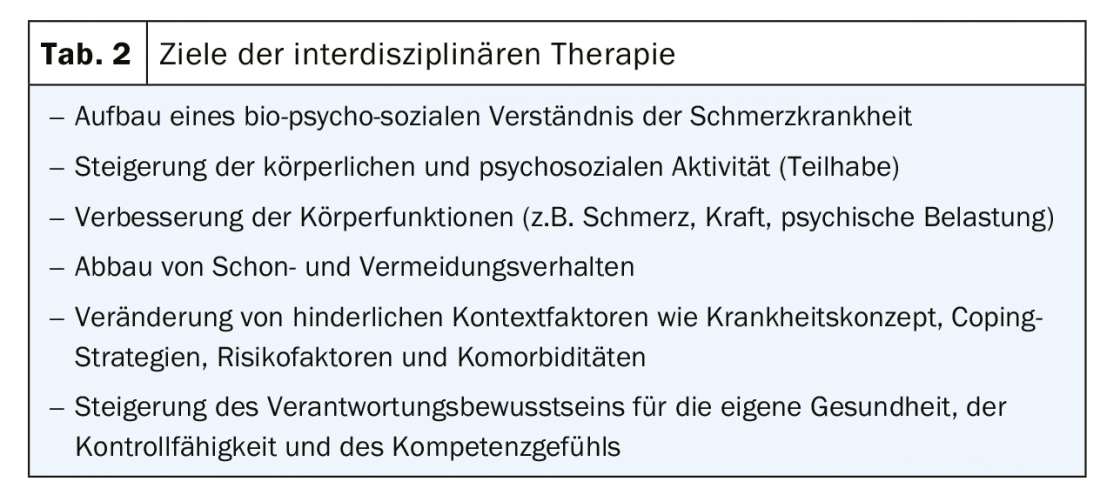

Chronic pain is a multifactorial event that can be explained and made understandable with a biopsychosocial approach. Accordingly, therapeutic approaches must also be multimodal in character and interdisciplinary in orientation, and today represent the gold standard in pain therapy. It is important to have a regular exchange between the disciplines (medicine, psychotherapy, physiotherapy), a common language and philosophy, in order to be able to convey an appropriate model of the disease to the patient and thus to make it easier to deal with the complaints in the long term, which necessarily includes dealing with psychosocial factors that increase pain.

Overarching goals of interdisciplinary therapy can be found in Table 2 [8].

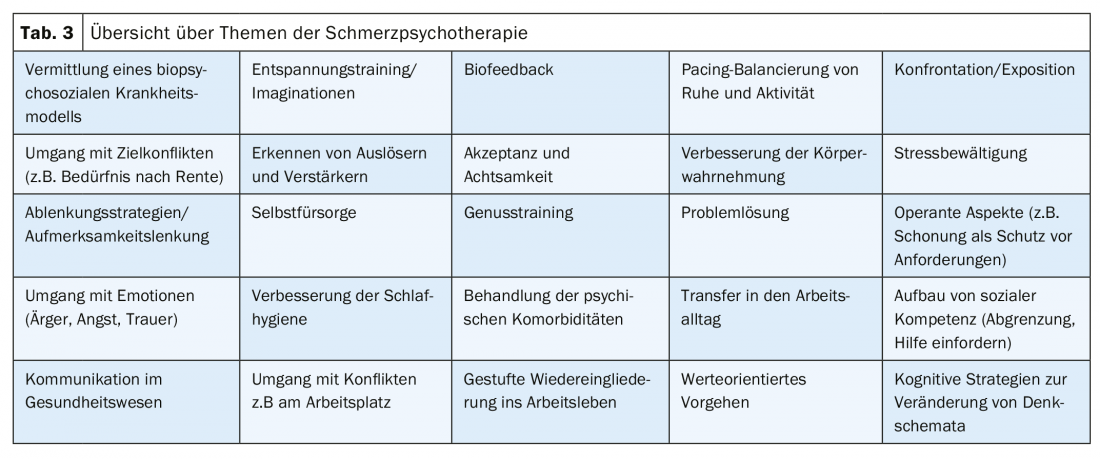

The goals of pain psychotherapy [9,10], in addition to eduction of a disease model, are to teach assimilative coping strategies to influence the symptom (e.g., by confronting avoided movements, better balancing rest and activity, relaxation techniques, distraction strategies). As chronicity increases, teaching accommodative coping strategies (e.g., increased flexibility in dealing with symptoms, building acceptance toward the symptom and its accompanying limitation) represents an important aspect. In addition, it is about improving the handling of factors influencing pain, such as stress competence training, dealing with professional and family stresses and, last but not least, dealing with possible biographical traumatization. Approximately one third of patients suffer from comorbid affective or anxiety disorders, which should also be treated in addition to the symptom-oriented approach.

In the following, some aspects are explained in a little more detail:

Patients with back pain often have a very somatic clinical picture, the aim of the education is to convey a biopsychosocial model of the disease, the difference between acute and chronic pain (pain processing, physiological processes of pain sensitization, maintaining factors) and to be well informed about one’s own possibilities of influence and also their limits.

With the help of biofeedback, physical signals can be fed back visually or also acoustically. Biofeedback finds a high acceptance – “there you can see my pain”. In somatically oriented pain model, it serves to improve compliance by teaching a biopsychosocial model, is also used to complement and illustrate the content of the eduction, and the ability to relax can be improved.

Relaxation techniques such as progressive muscle relaxation or even imaginative exercises are an integral part of pain psychotherapy and simultaneously pursue very different goals: muscular and vegetative stabilization, distraction from pain, improvement of body perception and stress management. In addition, relaxation techniques are suitable as an aid to falling asleep and staying asleep, and appropriate sleep hygiene strategies are taught.

To reduce fear of movement, the patient needs reassurance from a medical professional and an explanation of their somatic findings (e.g., x-ray, MRI) to engage in activating therapy and exposure to the avoided movements. “Fear of pain” is associated with fear of pain during a movement. The goal of confronting the feared stress is “reframing” (changing the belief that stress is harmful) and building more confidence in the body under stress. Joint treatment by psychologists and physiotherapists is often useful here. The psychologist guides the patient through the anxiety-inducing movement, and the physical therapist can also teach helpful strategies such as stretching or loosening after the stress.

Very deconditioned patients with generalization of avoidance behavior should be activated in a graduated manner (graded activity) according to a quota-based approach. The ratio is an exertion measure in which, for example, the time of exertion, the frequency of movement, or even the walking distance until pain intensifies are recorded. From this measure 20% is subtracted and thus the first quota for training is determined. If the patient copes well with this load during training, even on a bad day, he increases by 20% of the initial value. Activation by quota thus follows a pain-contingent procedure so that pain loses its discriminatory function in controlling behavior. Without this quota specification, the patient would stop loading due to pain. Quota-oriented approach is suitable in addition to dealing with the high performance demands and “inner drivers” in patients with a perseverance behavior and exceeding personal physical limits. Both under- and over-conditioning are avoided and the patient is praised for “healthy”, functional behavior (building up everyday stresses that are meaningful to him, such as household chores, work, going shopping, playing sports) according to the principles of operant conditioning.

Teaching accommodative coping strategies involves gaining greater flexibility in dealing with discomfort, reducing the discrepancy between goals and desires for the given circumstances by, for example, lowering the level of aspiration or setting realistic goals, and possibly coming to a reassessment of one’s situation. The techniques used here are primarily those of cognitive behavioral therapy. The role of one’s own inner drivers and dysfunctional basic beliefs are identified and questioned in order to be able to build more appropriate new inner attitudes. The goal is to develop a more flexible, adapted behavior and a more adaptive handling of requirements independent of the situation.

With the help of acceptance and commitment therapy, a value-oriented life and building a new perspective on life are pursued. It’s about building a willingness to leave things as they are at the moment and turn back to other important areas of life. However, some patients put all their energy into “fighting” their symptom. Mindfulness represents a basic competence and foundation in this context and is therefore practiced both in formal exercises (e.g. breathing mindfulness, body scan) and informal exercises in everyday life.

Other important topics often include building assertive skills to better distinguish oneself from demands by colleagues or family members, and also dealing with problems and conflicts in the workplace to enable a return to work.

Summary

Chronic pain represents significant health disorders. In the context of a biopsychosocial understanding of chronic pain, psychological and social factors are increasingly attributed significance in addition to the physical aspects of the complaints. Accordingly, it makes sense to offer not only a unimodal purely medically oriented therapy, but to work in an interdisciplinary way in the case of chronic back pain and to involve psychotherapy and physiotherapy equally.

Take-Home Messages

- Psychosocial and workplace factors, in addition to iatrogenic aspects in health care, contribute significantly to chronification and must be urgently addressed in therapy.

- Pain psychotherapy includes both a symptom-oriented and problem-oriented approach.

- Education promotes a higher acceptance of one’s own disease, reduces fears, supports coping with the disease and thus also increases the patient’s compliance for active therapy.

- In the case of chronic back pain, an interdisciplinary approach involving the fields of medicine, psychotherapy and physiotherapy is useful.

Literature:

- Schmidt CO, Raspe H, Pfingsten M, et al: Back pain in the German adult population: prevalence, severity, and sociodemographic correlates in a multiregional survey. Spine 2007; 32: 2005-2011.

- Fahland AR, Kohlmann T, Schmidt CO: From acute to chronic pain. In: Casser HR, Hasenbring M, Becker A, Baron R. (Eds.) Back and neck pain. 2016; 3-12. Berlin: Springer.

- Hildebrandt J, Schöps P: Musculoskeletal pain/back pain. In: Zens M, Jurna I. (Eds.) Textbook of pain therapy. 2001; 577-609. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, Main CJ & the “Decade of the Flags” Working Group: Early Identification and Management of Psychological Risk Factors (“Yellow Flags”) in Patients with Low Back Pain: A Reappraisal. Physical Therapy 2011; 91: 737-753.

- Linton SJ: A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine 2000; 25: 1148-1156.

- Hildebrandt J: The musculature as a cause of back pain. Pain 2003; 17: 412-418.

- Locher H, Nilges P: How do I chronify my pain patient? Orthopaedic Practice 2001; 37/10: 672-677.

- Arnold B, Brinkschmidt T, Casser HR: Multimodal pain therapy in the treatment of chronic pain syndromes. A consensus paper of the ad hoc commission Multimodal Interdisciplinary Pain Therapy of the German Pain Society on treatment contents. Pain 2014; 28: 459-472.

- Kröner-Herwig B, Frettlöh J, Klinger R, Nilges P. (Eds.): Pain psychotherapy. 2016; 8th ed. Berlin: Springer.

- Nilges P, Diezemann A. Chronic pain. Concepts, diagnostics and treatment. Behavior Therapy & Behavioral Medicine 2018; 39 (2): 167-186.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2020; 15(3): 4-8