The approval of some immunotherapies in MS differs in Switzerland sometimes significantly from those of neighboring countries. A group of neurologists, with the participation of the Swiss MS Society and the SNS, has therefore drawn up recommendations in the sense of a therapeutic consensus.

Multiple sclerosis affects about 10,000 patients in Switzerland according to the International MS Society [1], however, analogous to data from other countries, it can be assumed that there is a higher number of affected persons in Switzerland as well [2]. The incidence of the disease is increasing [3]. As a chronic inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS, the majority of MS is relapsing [4]. However, due to new therapeutic options, the 10-15% of primary progressive MS (PPMS) have recently become the focus of interest. To date, no therapy with a curative approach is known. However, the progression-modifying therapy landscape has expanded greatly in recent years, with about a dozen progression-modifying therapies now available to reduce relapse rate or disability progression and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-detectable activity, among others. Due to different mechanisms of action, modes of application and benefit-risk profiles, increasingly individualized therapy is becoming possible. This allows a targeted response to current life situations and desired goals such as walking ability, occupational aspects, or pregnancy [5].

This growing complexity requires guidelines in which indication, potential benefit as well as safety aspects and side effect profiles are discussed. Most of these guidelines are generally applicable. This includes, for example, the recommendation to start immunotherapy as soon as possible after diagnosis [5].

However, several aspects such as different benefit-risk assessments, different approval procedures, or different political, legal, and country-specific prioritizations often lead to divergent approvals of individual therapies in sometimes neighboring countries [6].

For example, for MS immunotherapies in Switzerland, there are sometimes significant differences in terms of approval (e.g. first vs. second-line therapy, patient groups) and safety requirements compared to the European area (European Medicines Agency, EMA).

In addition, in Switzerland, a cost-benefit evaluation by the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) is required for the inclusion of a drug in the Specialty List (SL) institutionally separate from the approval. The SL lists the preparations reimbursed by the compulsory health insurance as well as potential limitations.

Compared with neighboring countries, these special conditions lead to significant differences in the use of certain preparations. Specific approaches in Switzerland are based on these different approvals and limitations, so that corresponding country-specific considerations are necessary.

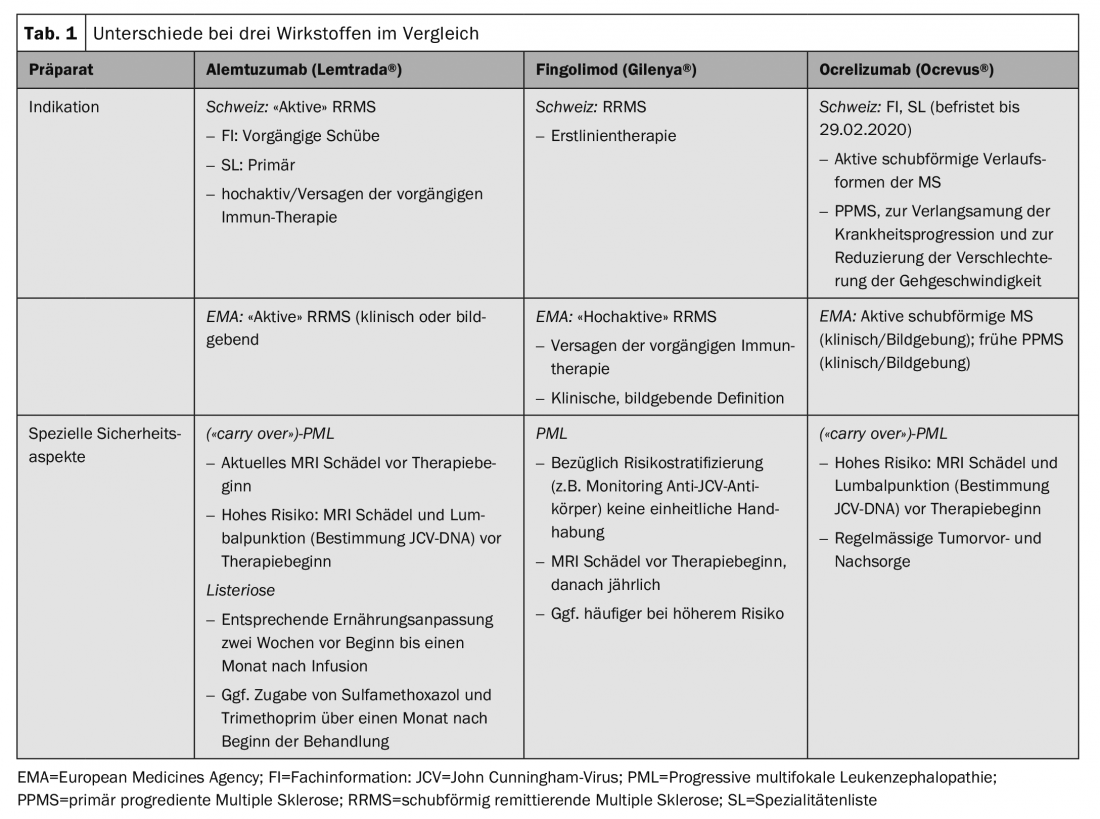

These specific aspects in Switzerland together with practical recommendations for action were summarized by a group of neurologists with a focus on MS therapy and coordinated in terms of a consensus with the scientific advisory board of the Swiss Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Swiss Neurological Society (SNS) [7]. Practical differences exist in particular for the substances alemtuzumab (Lemtrada®), fingolimod (Gilenya®) and ocrelizumab (Ocrevus®), as well as autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (aHSCT) (Table 1).

Indication

The use of some preparations requires a certain degree of disease activity, although the term “active” or even “highly active” MS is generally not clearly defined and is interpreted differently in the marketing authorization texts. Thus, the assessment of the treating physician plays a decisive role, which in turn has implications with regard to a possible cost approval application.

According to the Swiss SmPC, alemtuzumab can be used in active relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). This is defined clinically in terms of at least two relapse events in the two years prior to initiation of therapy (with at least one relapse in the year immediately preceding). The SL further restricts the indication and requires either failure of prior therapy or, in the absence of prior therapy, “primary highly active” MS, again without a clear definition of terms. According to the SL, a cost approval is required for non-pretreated patients with a highly active form of progression, which – due to the lack of a definition – requires an assessment of the individual situation, which is thus at the discretion of the treating physician. Especially in this group of patients, where the timely initiation of an efficient therapy is of particular relevance, it seems important to us to emphasize that formal aspects should not lead to a significant delay.

The limitations of the FI and SL, respectively, partially correspond to the inclusion criteria of the pivotal studies [8,9]. However, it correlates with current clinical practice that pre-therapy is not limited to glatiramer acetate or interferon-β, as was the case in the pivotal trial, but should also apply to the other approved immunotherapies.

In contrast to this relatively strict indication in Switzerland, a more general approval exists in the EMA space, where both clinical and imaging findings can be used to confirm disease activity. This, in turn, places greater demands on the prescribing physician’s individual risk-benefit evaluation.

A larger difference in terms of approval also exists for fingolimod. It is approved as a first-line treatment in Switzerland, but only as a second-line treatment in the EMA region. This can possibly be explained by a different benefit-risk interpretation, or above all by a different interpretation of the study population of the pivotal studies. In the FREEDOMS trials, 57% of patients were treatment-naive, and in the TRANSFORMS trial, 44% were [10,11]. Divergent aspects are also found with this preparation in terms of safety. In Switzerland, a therapy break is only prescribed when the lymphocyte value is below 100/μl, whereas the limit in the EMA region is 200/μl.

In contrast to the European approval, which is based on the study population of the pivotal trials, the indication for ocrelizumab in Switzerland is formulated much more generally both by Swissmedic and in the SL. An active, relapsing-remitting course is required, but this is not elaborated or limited. For the treatment of primary progressive MS (PPMS), the therapy was included in the SL without restrictions, which is understandable due to the lack of immunotherapeutic alternatives. The aim of therapy with Ocrevus® in this case is to slow down the progression of the disease, whereby this should not only refer to the ability to walk, but also to the preservation of other relevant residual functions such as arm/hand function or fine motor skills, in the sense of an individual benefit-risk assessment. Especially in this situation, a detailed and preferably quantified assessment of disease progression before and during therapy is essential (“Expanded Disability Status Scale”, EDSS; “Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite”, MSFC).

Especially younger patients with a shorter disease course and imaging detectable disease activity (contrast-enhancing lesions) seem to benefit from the therapy. However, the converse is not automatically true that patients without imaging disease activity are ineligible for therapy.

There are also different approaches for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (aHSCT), which has been approved in some cases in the EMA region or can be used according to expert opinion and was approved in Switzerland by the FOPH on July 1, 2018, subject to strict conditions for reimbursement by the OKP. Treated patients, for example, should be recorded in a registry. Due to the broad therapeutic alternatives for relapsing forms of the disease, potentially severe side effects of this invasive treatment, and in the absence of controlled randomized trials, the therapy remains controversial. Currently, it is recommended that they be used only in carefully selected cases and at highly specialized academic centers for the time being. Criteria for which appropriate therapy might be discussed include the lowest to moderate degree of disability (up to EDSS 6.5), younger patient age (<50 years), shorter disease duration (<10 years), and failure of prior highly active immunotherapy.

Special safety aspects

General safety aspects such as laboratory controls are outside the scope of this article and the consensus recommendation and can be found in the respective technical information.

In general, therapies should be administered by MS-experienced neurologists at centers that can safely monitor and assess patients and detect and treat side effects early.

In this context, special mention should also be made of imaging examinations and progress controls. MR tomographic imaging has a growing importance not only in the field of diagnostics, but also in the context of safety investigations. For this reason, regardless of established immunotherapy, follow-up should use standardized protocols and be assessed by neuroradiologists with appropriate experience [12].

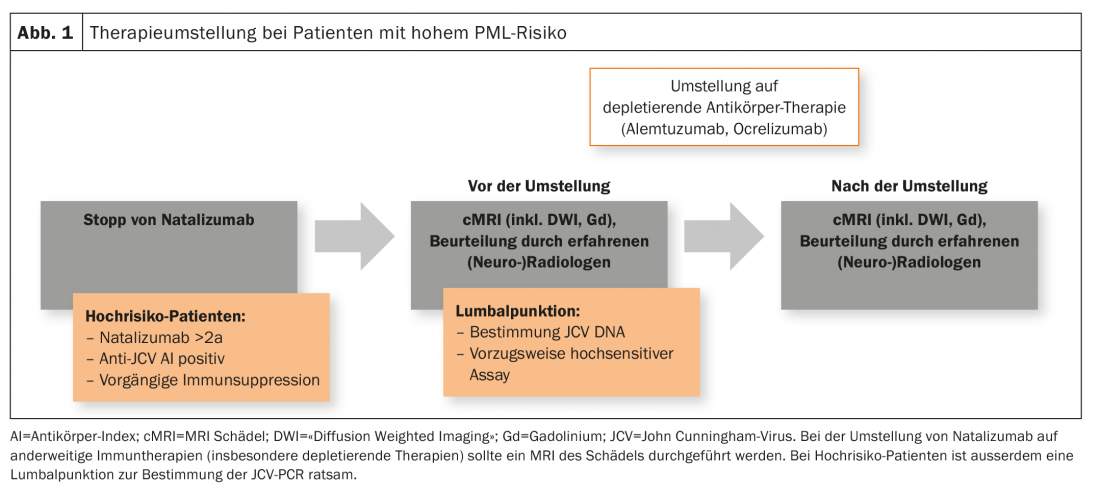

Cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an opportunistic viral infection of the CNS, have been described among several immunotherapy agents. Thus, of the agents discussed here, several cases have been described with fingolimod, corresponding to a general risk of 1/15,000 patients, and several “carry over” cases with ocrelizumab and alemtuzumab after prior therapy with natalizumab or fingolimod [13].

Patients at high risk (duration of therapy with natalizumab ≥2 years, anti-JCV antibody positive, prior immunosuppression) should receive a recent cranial MRI as part of a change in therapy. In addition, a lumbar puncture with determination of JCV DNA (preferably in a highly sensitive assay) is also advisable. This applies in particular to the switch from natalizumab to depleting therapies such as alemtuzumab or ocrelizumab, but is also performed in certain centers when switching from or to fingolimod (Fig. 1). However, there is no consensus on this in Switzerland.

Swiss Public Assessment Report

Within the framework of the revision of the Therapeutic Products Act (TPA, Art. 67), Swissmedic publishes additional information of general interest in the field of therapeutic products. For example, in the case of medicinal products for human use, a summary assessment report (“Swiss Public Assessment Report”, SwissPAR) is drawn up following a decision to approve or reject a marketing authorization in order to increase the transparency of the approval process. This is all the more important as other countries (e.g. developing countries) take their cue from the Swiss approval [6,7].

Literature:

- MS International Federation: Atlas of MS. www.msif.org/about-us/who-we-are-and-what-we-do/advocacy/atlas, last accessed 02/28/19.

- Dippel FW, et al: Health insurance data confirm high prevalence of multiple sclerosis. Act Neurol 2015; 42(4): 191-196.

- Koch-Henriksen N, et al: Incidence of MS has increased markedly over six decades in Denmark particularly with late onset and in women. Neurology 2018; 90(22): 1954-1963.

- Noseworthy JH, et al: Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 343(13): 938-952.

- Montalban X, et al: ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mul Scler 2018; 24(2): 96-120.

- Dalla Torre Di Sanguinetto S, et al: A Comparative Review of Marketing Authorization Decisions in Switzerland, the EU, and the USA. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2019; 53(1): 86-94.

- Achtnichts L, et al: Specific aspects of Immunotherapy for Multiple Sclerosis in Switzerland: a structured Commentary. Clinical and Translational Neuroscience [in press).

- Cohen JA, et al: Alemtuzumab vs interferon beta 1a as first-line treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012; 380(9856): 1819-1828.

- Coles AJ, et al: Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012; 380(9856): 1829-1839.

- Kappos L, et al: A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Oral Fingolimod in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. N Enl J Med 2010; 362: 387-401.

- Cohen JA, et al: Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. N Enl J Med 2010; 362(5): 402-415.

- Traboulsee A, et al: Revised Recommendations of the Consortium of MS Centers Task Force for a Standardized MRI Protocol and Clinical Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Follow Up of Multiple Sclerosis. Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37(3): 394-401.

- Berger JR, et al: Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after fingolimod treatment. Neurology 2018; 90(20): 1815-1821.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(2): 28-30.