Which supplements (sports supplements, medical supplements, performance supplements) are legal and appropriate in which situation? What is known about effects and side effects? How can one obtain the most objective evidence-based information on this? This article provides answers to these questions and more.

The use of supplements in sports is widespread today [1]. Prevalence data in sports are often higher than in the general population. Presumably because in sports there are additional motivations for taking supplements, such as the expectation of increased performance associated with supplement use.

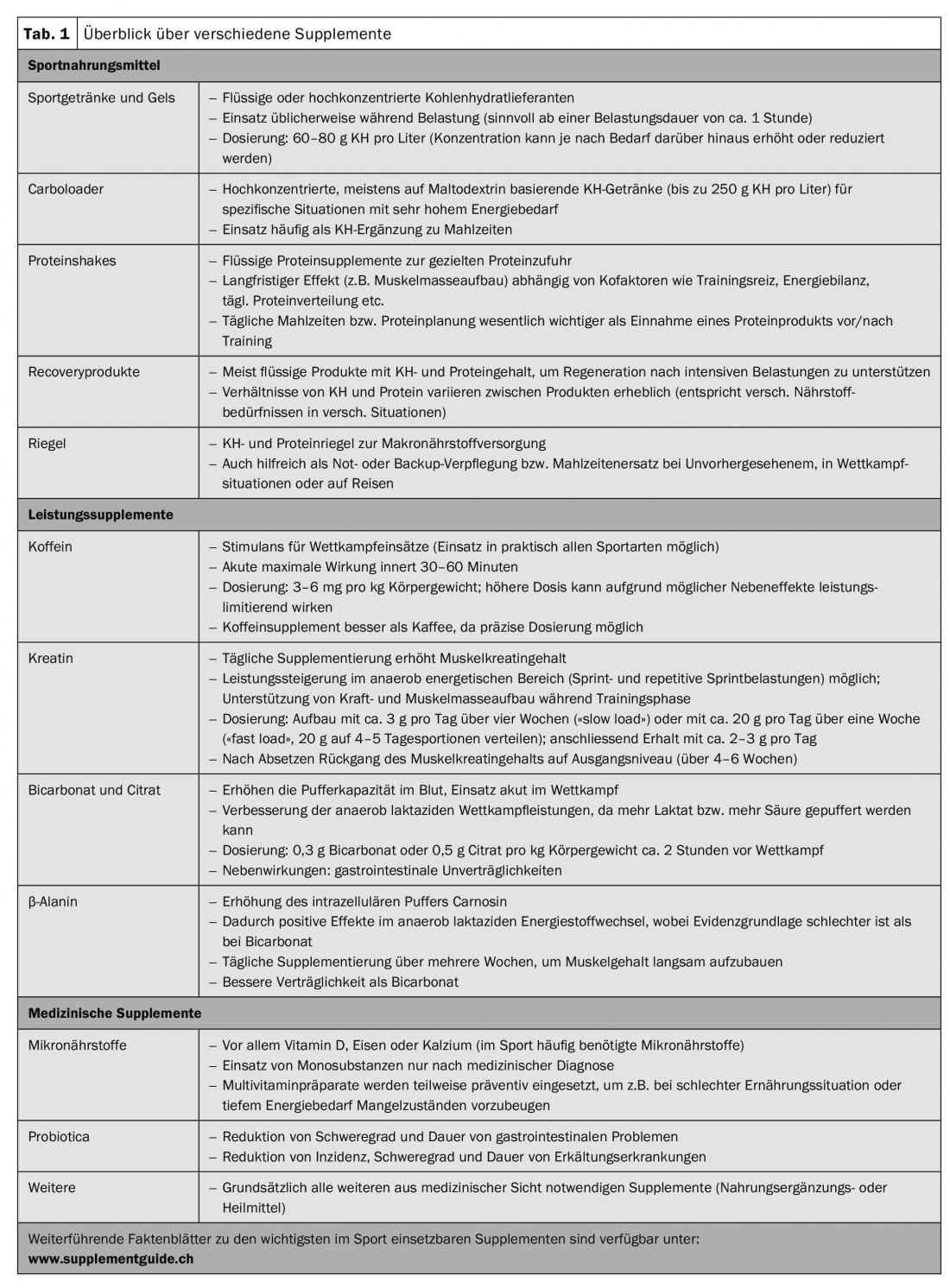

Supplements cover a wide range of products. They may be subject to either the Food Act (“food supplements”) or the Therapeutic Products Act. In sports, supplements are often divided into different categories: The essential function of so-called sports foods (“sport food”) is to provide macronutrients – mainly carbohydrates or protein. In addition, there are a number of other substances that promise to improve performance directly at the competition or indirectly via improved training effects. These products are referred to as performance supplements. In addition, there are products that do not directly target physical or mental performance, but can support health. This includes, for example, vitamin and mineral preparations or probiotics, or basically all supplements used for medical reasons. Of course, it is also central in sports to avoid deficiencies, e.g. of iron, and to correct them when necessary.

Component of sports nutrition

Sports nutrition is essentially based on a normal balanced diet, which is adapted to sporting needs. For example, athletes need more energy or the diet must be adjusted after exercise so that maximum performance can be regained as quickly as possible. In such situations, supplements can help to better meet individual, sport-specific needs.

In practice, it is problematic that athletes often focus on supplements, but neglect elementary basics of sports nutrition. A classic question is “I have a problem, what supplement can help here?”. But if underlying factors that limit performance and recovery are not addressed, the potential of supplements cannot be maximized. For example, if the daily meals are not adapted to the type of sport as well as the individual needs, even a recovery product cannot solve the problem.

Disinformation on the Internet

In the pre-Internet age, Philen et al. [2] identified 311 products with a total of 235 ingredients in twelve randomly purchased fitness magazines. Today, thousands of products are advertised to athletes with promises that are often unrealistic. Especially on the Internet, the market is largely uncontrolled. In addition to the promised effects, providers rarely point out side effects, let alone that the supplement could even endanger health. The majority of information about sports nutrition and supplements available on the Internet comes from the suppliers themselves, serves to promote sales and is therefore rarely well-founded. For the layperson, such misinformation is almost impossible to judge, and the increasing use of social media today additionally promotes the spread of unfiltered lay and disinformation.

Evidence-based, neutral information on supplements is, however, available as scientific publications, such as the current IOC consensus statement [2] or supplement guides, which serve as online sources of information for athletes and professionals [3].

Unfortunately, in practice, it appears that especially among young athletes, non-specialists such as family members and coaches are the main recommending authorities for the use of supplements [4]. We also found comparable results in a recent survey of top Swiss young athletes.

Benefit versus risk

There is a broad evidence base for some supplements, so performance-supporting potential is possible if these products are used correctly. Examples are caffeine or creatine (tab. 1). Sports foods facilitate optimized timing and precise dosing of the desired nutrient intake, even though they are often no better than the intake of identical nutrients via food. In extreme situations, specifically tailored nutrients may be necessary. If, for example, up to 90 g of carbohydrates per hour are consumed in the endurance range in order to maximize performance, then this is only possible with a specific sugar ratio of glucose to fructose [5], and in this respect many of the commercially available sports drinks have been optimized.

On the risk side, the primary consideration is product safety. This is a significant problem, especially in the international market and in Internet commerce. An international study found that 15% of all supplements purchased were contaminated with undeclared anabolic steroids [6], with even simple vitamin C, multivitamin, or magnesium tablets contaminated with stanozolol or methandienone [7]. Both substances are on the doping list. On the one hand, these are micropollutants. On the other hand, these substances are probably deliberately added to help ineffective products achieve a subjectively perceivable “effect”. Also a perennial favorite is sibutramine, which is banned as a stimulant and is often used in slimming products or weight loss products.

For reasons of doping safety and health, care must be taken accordingly to ensure that primarily only sensible products are used and purchased as safely as possible. The established Swiss brands, which are also available in retail and sports retailers, seem to be safe so far. The renowned Swiss brands in the micronutrient sector can also be considered safe. Purchases from Internet stores, on the other hand, are practically taboo. Due to the quality and safety issues for athletes, various quality labels now exist, such as the Kölner Liste® [8], Informed-Choice [9] or NSF [10]. Unknown or foreign brands and products should only be used if they are on one of these lists. Products from the therapeutic products sector are considered safer due to the higher production standards.

Placebo and nocebo effects

If an effect of a treatment is assumed, positive (placebo) as well as negative (nocebo) effects can result from it. Thus, wine tastes better when the same bottle is labeled more expensive [11] and athletes’ performance can be acutely improved when an effect is believed [12,13]. Not only can performance be improved, but training adaptations can also be positively supported [14].

If an athlete is appropriately convinced that a product works, an effect is highly likely to occur, regardless of whether an ergogenic effect is even scientifically possible. This can, of course, make sound advice much more difficult. Simply discontinuing a product could remove a performance-relevant placebo effect. Nevertheless, this should not be seen as a free pass to use any products. Focusing on the supplements mentioned in Table 1 offers the advantage that an additional evidence-based effect can occur. In addition, this type of approach minimizes risks and also allows financial resources to be used in a targeted manner.

Example creatine

On the one hand, creatine can improve sprint performance, especially short repetitive interval sprint performance, via anaerobic energy supply. On the other hand, building muscle mass and strength can be supported in an exercise program [1]. Moreover, creatine could be interesting not only for young athletes, but also exert positive effects on the preservation of muscle mass in old age [15]. If creatine is used adequately, hardly any side effects are to be expected. However, there are a few points to consider with regard to practice. While many athletes tolerate creatine well, there are others who react to it with increased muscle tone and increased susceptibility to muscle injury or associated tendon problems. In addition, differences exist in the effect. While individual athletes hardly feel anything, others report positive effects regarding sprint performance, regeneration or muscle building. In the case of muscle mass gain, an individual assessment must be made as to whether this is desirable. For a bodybuilder, muscle mass is the only goal and therefore an increase is positive. For a thrower, muscle mass gain is mostly positive as absolute strength helps. However, for a sprinter, runner or jumper, increased muscle mass can also have disadvantages because muscle mass cannot always be profitably converted into power (relative strength) or running economy can suffer (e.g. elastic energy recovery during running). It is also often underestimated that more weight means more load on the passive musculoskeletal system and tendons in the long term.

Creatine is a good example of a supplement whose effect is clearly proven. However, in order to use it profitably, the individual case must be precisely assessed on a sport-specific basis and, if it is used, it must be monitored in a targeted manner.

Example caffeine

Unlike creatine, which must be taken over a long period of time to increase the amount of creatine in the muscles, caffeine is used selectively for competitions. Caffeine is probably the most “universal” supplement of all. Positive performance effects are possible in endurance, sprint, strength, reaction as well as concentration sports [1,16]. Accordingly, caffeine is an interesting and potentially effective competition supplement for the marathon runner as well as for the football player, fencer, sprinter or jumper. Tolerance is largely good. While caffeine is consumed in everyday life in the form of coffee, it can be taken more easily and more precisely dosed as a supplement in sports.

Literature:

- Maughan RJ, et al: IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Br J Sports Med 2018; 52: 439-455.

- Philen RM, et al: Survey of advertising for nutritional supplements in health and bodybuilding magazines. JAMA 1992; 268(8): 1008-1011.

- Maughan RJ: Supplementguide. www.ssns.ch/sportsnutrition/supplemente/supplementguide, last accessed 12/6/18.

- Braun H, et al: Dietary supplement use among elite young German athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2009; 19(1): 97-109.

- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM: Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics, dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: nutrition and athletic performance. J Acad Nutr Diet 2016; 116(3): 501-528.

- Geyer H, et al: Analysis of non-hormonal nutritional supplements for anabolic-androgenic steroids – results of an international study. Int J Sports Med 2004; 25(2): 124-129.

- Geyer H, et al: Nutritional supplements cross-contaminated and faked with doping substances. J Mass Spectrom 2008; 43(7): 892-902.

- Cologne List®. www.koelnerliste.com, last accessed 12/6/18.

- Informed-Choice. www.informed-choice.org, last accessed 12/6/18.

- NSF International. www.nsfsport.com, last accessed 12/6/18.

- Plassmann H, et al: Marketing actions can modulate neural representations of experienced pleasantness. PNAS 2008; 105(3): 1050-1054.

- Benedetti F, et al: Conscious expectation and unconscious conditioning in analgesic, motor, and hormonal placebo/nocebo responses. J Neurosci 2003; 23(10): 4315-4323.

- Pollo A, Carlino E, Benedetti F: Placebo mechanisms across different conditions: from the clinical setting to physical performance. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2011; 366(1572): 1790-1798.

- Ariel G, Saville W: Anabolic steroids: the physiological effects of placebos. Med Sci Sports 1972; 4(2): 124-126.

- Candow DG, Chilibeck PD, Forbes SC: Creatine supplementation and aging musculoskeletal health. Endocrine 2014; 45(3): 354-361.

- Goldstein ER, et al: International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2010; 7(1): 5.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(2): 19-22