Central nervous system (CNS) infections often lead to changes in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF examination allows not only the detection of inflammation in the CNS and thus the localization of the focus of infection, but occasionally also the identification of the causative pathogen. CSF examination results should always be viewed in a clinical context and often supplemented by findings from blood tests and imaging.

Examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is of particular importance in patients suspected of having an acute infectious disease of the CNS. The distinction between a meningitic and an encephalitic syndrome, which is of particular importance for the specific microbiological diagnosis and also an empirical therapy, is mainly made on the basis of clinic and imaging, but clues also result from CSF diagnostics.

Unless there are contraindications (especially signs of intracranial pressure due to the CNS disease), a lumbar puncture (LP) should be performed quickly. If possible, the puncture should be performed in the lateral position so that the opening pressure can be measured. The amount of CSF that can be safely collected is not precisely known, but is likely to be greater in adults than in children and at least 15 ml lie.

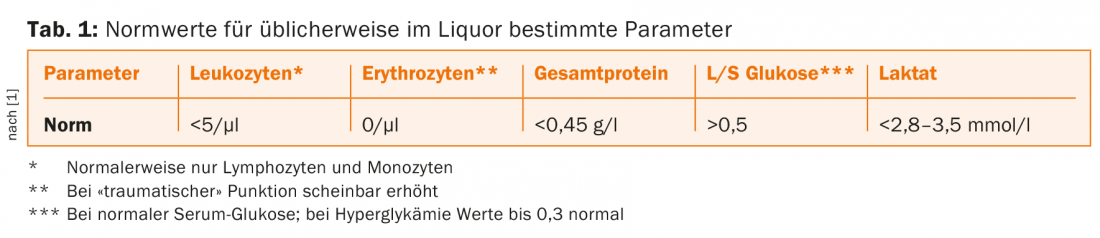

After visual inspection (turbidity occurs from around 200 leukocytes/µl), the CSF should be sent to the laboratory for quantification of leukocytes (including differentiation) and erythrocytes, total protein, glucose and lactate. This should also be done without delay, if possible, because in vitro lysis of leukocytes already occurs after one to two hours. Corresponding standard values for these routine parameters can be found in table 1.

A Gram stain and bacterial culture should always be requested, except when only looking for a specific pathogen (such as in the workup of possible neuroborreliosis). Further investigations, in particular molecular biological PCR analyses to search for viral pathogens, are to be performed depending on clinical (in particular also epidemiological) considerations. Here, look for diseases that can be treated and require treatment, especially herpes simplex or varicella zoster viruses. However, detection of common but untreatable viruses such as enteroviruses can also be helpful, as it allows a more specific prognosis and also a waiver of further investigations.

It should be noted already at the time of collection that especially the sensitivity of culture methods for the detection of bacterial pathogens is influenced by the amount of CSF available. Especially when tuberculous meningitis is suspected, it is recommended to use at least 6 ml of CSF (preferably more) for culture only. Finally, blood cultures should also be taken from all patients with suspected CNS infection, and HIV testing should be performed, given the different pathogen spectrum in immunosuppressed individuals. The following is a brief discussion of some of the most common issues in the interpretation of CSF findings in acute illness.

Infection with normal cell count?

In patients with neurologic symptoms (headache, impaired consciousness, confusion, focal signs) on the one hand and fever and other systemic signs of infection on the other, the question often arises whether a primary CNS infection is present or whether the neurologic symptoms are an expression of septic encephalopathy. A normal leukocyte count in CSF argues against intrathecal inflammation and thus against infection of the CNS. Although rare, cases of bacterial meningitis and also herpes encephalitis have been described in which there was no pleocytosis in the CSF early in the course of the disease. In neutropenic patients, the absence of CSF pleocytosis is likely to be even more common. Therefore, if clinical suspicion is high, empiric treatment should be given and lumbar puncture should be repeated after one to two days.

Conversely, CSF pleocytosis without appropriate context does not, of course, prove CNS infection: autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as an episode of multiple sclerosis, often result in mild mononuclear pleocytosis, although rarely with as high a cell count as many CNS infections. Drug-induced meningitis from NSAIDs, certain antibiotics, or intravenous immunoglobulins may even show the same CSF composition as bacterial meningitis.

Viral or bacterial?

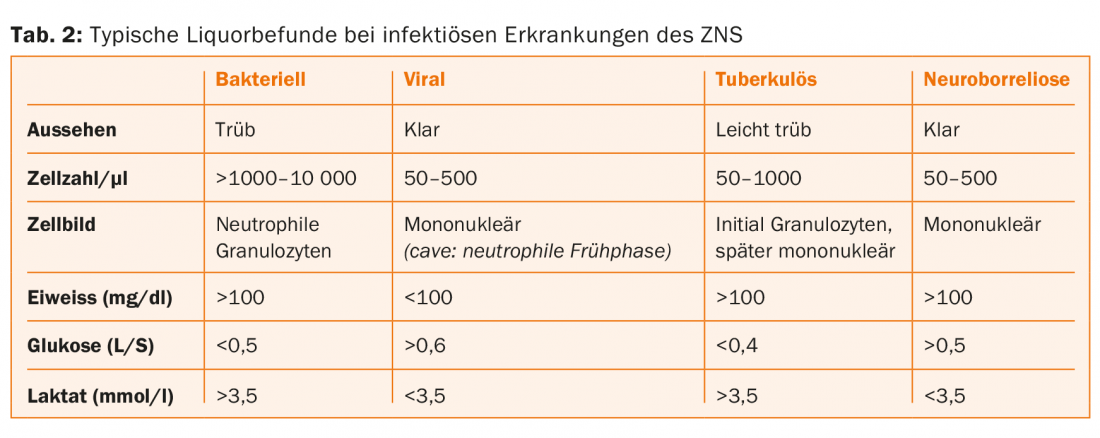

Not least because specific pathogen detection is often unsuccessful, the routine parameters of the CSF examination are used as criteria for distinguishing a viral from a bacterial etiology (Table 2).

Unfortunately, in many cases the classic findings are not found. Although on average the cell count and the percentage of neutrophils in all leukocytes are significantly higher in bacterial meningitis and the CSF glucose resp. the CSF/serum index for glucose is significantly lower than for viral disease, but neither of these parameters is a reliable discriminator. In particular, if bacterial meningitis has been treated with antibiotics for some time before the lumbar puncture is performed, typical “viral” findings are often seen. Conversely, in viral meningoencephalitis, such as with enteroviruses, there may be predominantly neutrophilic pleocytosis in the early stages.

Although lactate and procalcitonin should not be used as sole criteria, a CSF lactate <3.5 mmol/l and a serum procalcitonin <0.5 µg/l seem to strongly suggest against bacterial meningitis.

The treatment has already been started

Pathogen diagnosis is complicated in bacterial meningitis if antibiotics have been administered prior to LP. Of course, this should not lead to a delay in antimicrobial therapy if suspected. While the cell count probably usually remains elevated for several days even under antibiotics (often even after successful completion of treatment), the sensitivity of Gram preparation and culture decreases in this situation. Sometimes antigen testing or molecular biology methods (PCR) can be helpful in these cases.

How to find the tuberculosis?

With a sometimes acute, but often subacute to chronic presentation, tuberculous meningitis presents a particular diagnostic challenge. Although certain routine parameters such as increased opening pressure, usually moderate (around 300/µl), predominantly mononuclear CSF pleocytosis, and hyperproteinorrhachia and hypoglycorrhachia may be suggestive of tuberculous meningitis, the diagnosis is based on germ detection. Both the Ziehl-Neelsen preparation and PCR from CSF should have a sensitivity of around 60% for this. The results of the culture, which remains the diagnostic gold standard, are not available for several weeks.

Chronic infections

Among chronic infections of the nervous system, those caused by spirochetes in particular are often clarified by CSF examination. As in the diagnosis of some other prolonged CNS infections (such as herpes encephalitis persisting for more than a week), serologic methods with evidence of intrathecal antibody production play a special role. For this purpose, antibodies are measured in CSF and serum and the CSF/serum index is calculated from this.

Neurolues

Which asymptomatic patients with positive blood serology should receive a lumbar puncture is controversial. When CSF is examined, mononuclear pleocytosis of >10/µl is expected in all stages of neurolues and hyperproteinorrhachia is also found as a nonspecific finding. VDRL in CSF is considered a particularly specific test and thus a diagnostic gold standard, but has a sensitivity of only 30-70%. In contrast, a treponeme-specific test (such as TPHA) in CSF is considered very sensitive. So if it comes out negative, neurolues is very unlikely. In unclear cases, a CSF/serum index may also be helpful.

Neuroborreliosis

For the diagnosis of neuroborreliosis, in addition to a suitable clinic, CSF examination is essential. For a definite diagnosis, the EFNS guidelines require CSF pleocytosis (usually mononuclear between 10-1000/µl) and intrathecal production of specific antibodies, which is detected by determination of a CSF/serum index. In early neuroborreliosis, antibody detection in CSF is reported to have a sensitivity around 70%, and in chronic infection towards 100%. It should be noted that a positive CSF/serum index may persist for years after successful treatment of neuroborreliosis.

Literature:

- Deisenhammer F, et al: Cerebrospinal Fluid in Clinical Neurology. Springer 2015.

Further reading:

- Hasbun R: Cerebrospinal fluid in central nervous system infection. In: Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM.

- Infections of the central nervous system. Wolters Kluwer Health 2014.

- Mygland A, et al: EFNS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of European Lyme neuroborreliosis. European Journal of Neurology 2010; 17: 8-16.

- Thwaites G, et al: British Infection Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the central nervous system in adults and children. Journal of Infection 2009; 59: 167-187.

- Venkatesan A, Griffin DE: Bacterial infections. In: Irani DN: Cerebrospinal fluid in clinical practice. Saunders 2009.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(4): 4-6.