Vasculitis is a very heterogeneous disease. When the skin is involved, additional involvement of other organs may be present or absent. In addition, systemic vasculitis can also affect the skin. Hand eczema is common and comes in various forms and stages.

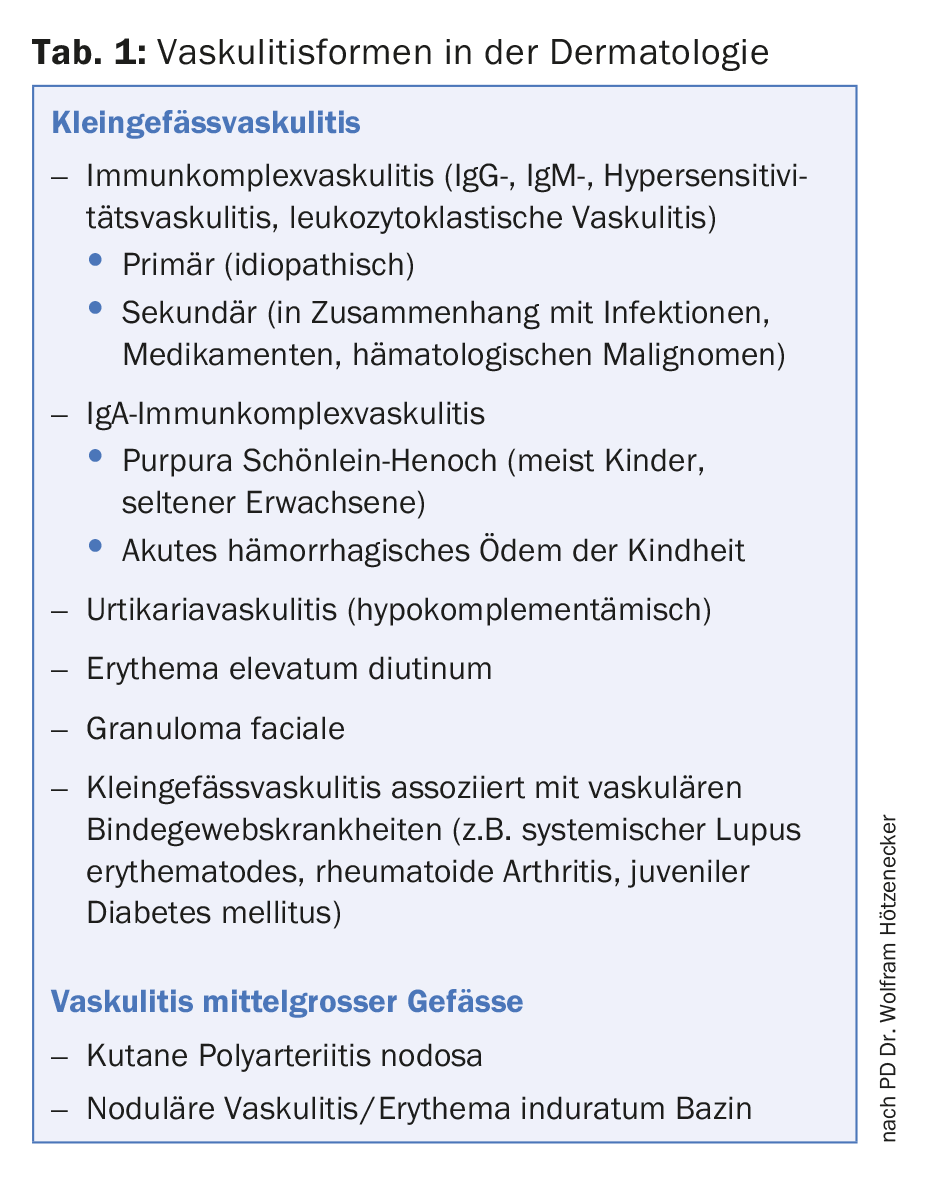

Private lecturer Dr. Wolfram Hötzenecker, Primarius of the Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Kepler University Hospital, Linz, Austria, spoke about vasculitis in the session “Neglected Allergic Disease”. This is an inflammation of the vessel wall that can result in tissue damage. The commonly used vasculitis classification from the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference is based on the size of the affected vessels. Various forms of small vessel vasculitis are mainly noticeable on the skin, affecting arterioles, capillaries and postcapillary venules. Table 1 provides an overview of vasculitis forms encountered in dermatology.

Diagnosis and therapy of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis

Cases of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis are not uncommon in dermatologic practice. In most cases, vasculitis begins with palpable purpura in hydrostatically stressed regions (lower legs, forearms) that cannot be pushed away. Later, blisters may form or necrosis and sometimes deep ulcers that are difficult to treat. In half of the cases, the cause of vasculitis remains unknown. Infections, autoimmune connective tissue diseases, or drugs are each responsible for vasculitis in about 15% of cases, and neoplasms in 5%. An antigen trigger (e.g. infection, drug, cancer antigen) together with antibody and complement forms immune complexes that attack the walls of small skin vessels and cause livedo, palpable purpura, and tissue damage such as necrosis and ulcers. Histologic examination reveals leukocytoclasia (cell fragments of neutrophil granulocytes) in the biopsy.

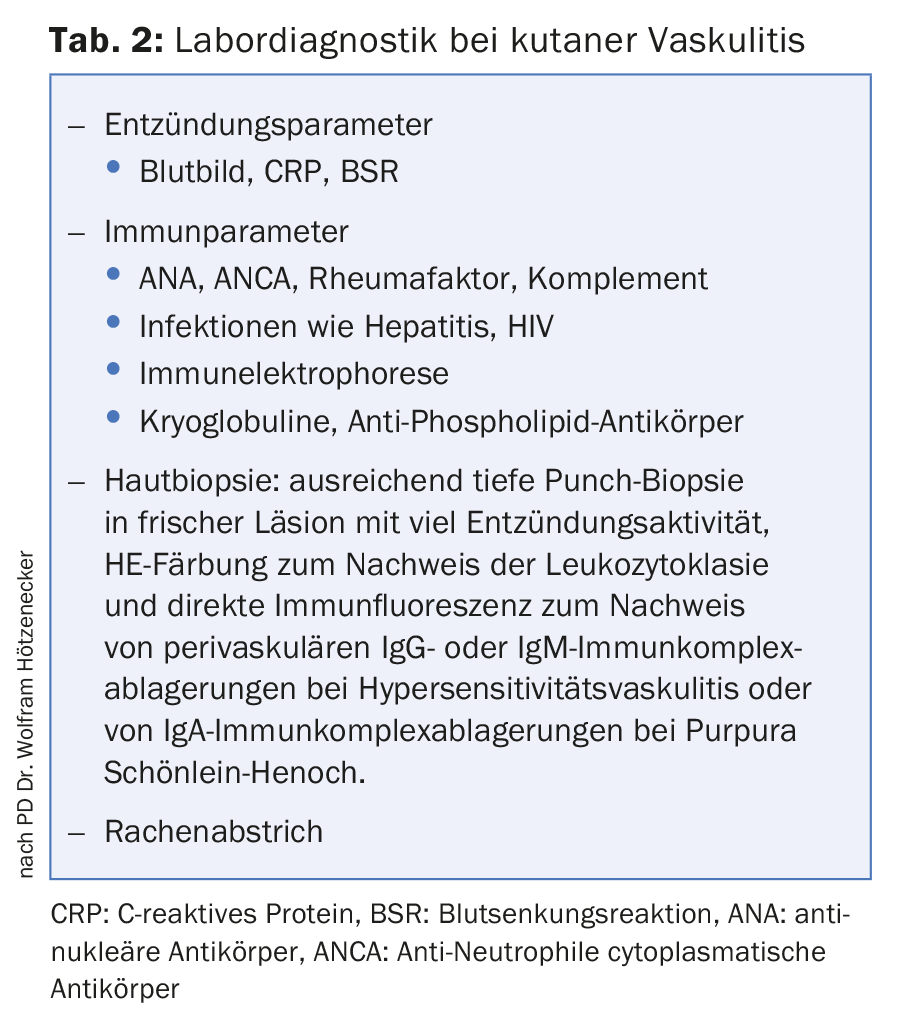

Table 2 lists the laboratory tests that are recommended when cutaneous vasculitis has been diagnosed based on the clinical picture. In cutaneous vasculitis, secondary involvement of other organs must also be sought (history, clinical examination, urinalysis, chest radiography, abdominal ultrasonography).

Hypersensitivity reactions to drugs account for up to 15% of cases of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. The triggering drugs are mainly antibiotics and painkillers. In addition, TNF-alpha blockers, psychotropic drugs (e.g., clozapine, thioridazine), allopurinol, and various other drugs can be considered as triggers. Allergic workup options are limited in drug-induced vasculitis. Sensitivity, specificity, and safety of skin testing are not known, the speaker said. Published case reports had described that patch testing could trigger vasculitis recurrences. Prick testing is of little value because pathogenetically it is a type III hypersensitivity reaction.

For the treatment of mild forms of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, bed rest, compression therapy of hydrostatically stressed regions, discontinuation of triggering drugs, and therapy with topical corticosteroids are usually sufficient. If lesions progress (hemorrhagic blisters, necrosis, ulcers), systemic corticosteroids and occasionally dapsone or colchicine are needed.

Classification and therapy of hand eczema

Over the course of the disease process, the morphology of hand eczema can change significantly. Initially, redness, edema, and vesicles are often prominent, followed by hyperkeratosis and rhagades, reported Prof. Thomas Diepgen, MD, Department of Clinical Social Medicine, Heidelberg University Hospital, Germany. The guidelines developed by a working group of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis (ESCD) distinguish three hand eczema phases: acute, subacute, chronic [1]. Acute or subacute hand eczema is present for less than three months and does not recur more frequently than once a year. Hand eczema is chronic if it persists consistently for more than three months or if it recurs twice a year or more frequently.

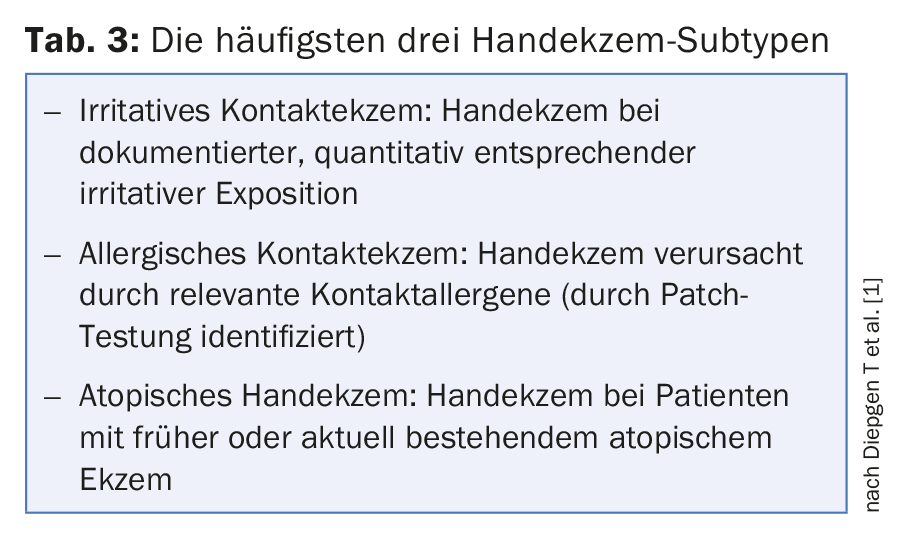

Hand eczema may be localized on the palm, between the fingers, or on the back of the hand, although the location may change over time. If the palmar side of the wrist is also affected, he thinks primarily of atopic hand eczema, Prof. Diepgen said. He recommended inspecting not only the hands, but the whole body, especially the feet. Chronic hand eczema is most commonly irritant contact dermatitis. Table 3 lists the three most common subtypes of hand eczema. Less common are endogenous forms of hand eczema such as pompholyx (recurrent hand eczema with vesicle formation and without relevant contact allergy or irritant exposure) or hyperkeratotic palmar eczema of the palms (without vesicles or pustules and without irritant exposure). Many chronic hand eczemas are mixed forms. In the endogenous forms of hand eczema (vesicular or hyperkeratotic hand eczema), the feet are also affected by eczema in half of the cases, the speaker reported. Prof. Diepgen recommends patch testing in all patients with hand eczema that persists for more than three months or that recurs to clarify the role of contact allergens in the environment.

Acute hand eczema should be treated quickly and intensively to avoid chronicity. Identification and avoidance of causative exogenous factors is recommended [1]. All patients with hand eczema need emollients, which should be selected individually according to the skin condition. Topical corticosteroids are very efficient when used in the short term. However, they should not be used for longer than six weeks if possible (risk of skin barrier defects and skin atrophies). Emollients are always part of topical corticosteroid therapy, the speaker emphasized.

Literature:

- Diepgen T, et al: Guidelines for diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hand eczema. Journal of the German Dermatological Society 2015; 13: e1-e22.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(3): 35-37